How should we view the fall of a great man in a post-patriarchal age? A blog on preparing to see Lila Raicek’s ‘My Master Builder‘ on Tuesday 8th July at Wyndham’s Theatre, London. I consider some ways in which her play re-sees what Raicek calls Henrik Ibsen’s ‘autobiographical play’, ‘The Master Builder’ [‘Bigmester Solness’].

My Master Builder is a title that already seems to revise the great and classic play that it refers to, The Master Builder by Henrik Ibsen. On the title page of her play Lila Raicek confidently refers to this play as Ibsen’s ‘autobiographical play’, though it is no more and no less autobiographical that many of his ironic tragedies of the fall of great men.

I need to modify the term ‘tragedy’ with the adjective ‘ironic’ because of the extent to which his plays dealing with that topic are in fact solely tragedies. Both in genre or tone, the full blown effect of the term ‘tragedy’ is often highly questionable. We shall see that he questioned the tragic status of his male heroes, most obviously in that tremendous play, John Gabriel Borkman. Although it’s there in all of those strangely crafted semi-poetic-realist dramas. I think anyway that Ibsen launched a dramatic revolution, wherein the verities of classic drama would be entirely up for grabs: the result in his dramas somewhat akin to what later might be called magic realism.

The verities of classical drama queried include the characterisation of the tragic hero by Aristotle. Let’s take the most basic characterisation of the tragic hero which Charles Reeves in 1952 believed to be the simplest formulation within Aristotle’s otherwise puzzling overall definition. He says that Aristotle’s basic contention was that tragedy was, like comedy, a drama imitative, or representing a likeness of, human beings, but that tragedy is [1]:

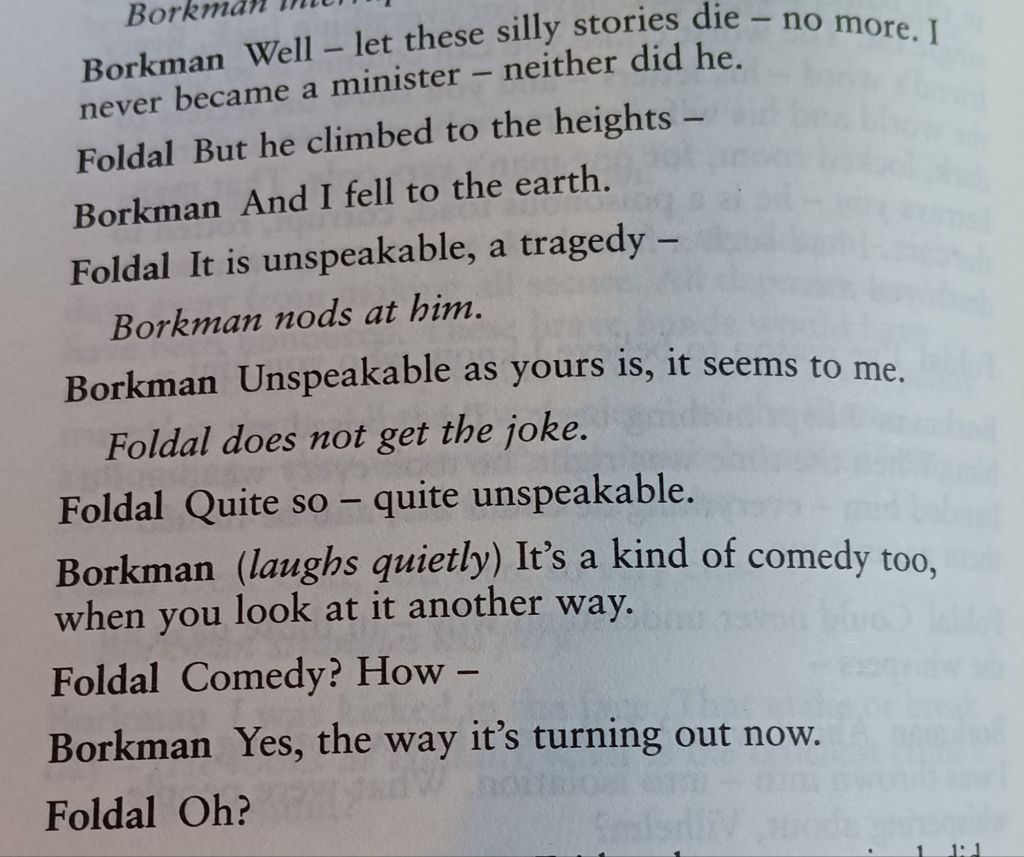

Ibsen knew the theory of Aristotelian tragedy well enough to play with it. Hence, in Act 2 of John Gabriel Borkman, disgraced eponymous ‘hero’ tragedy, of whom few people in tne play, other than himself see as much of a ‘hero’ at all, he introduces the character Vilhem Foldal, a ‘minor poet’ who also says that in ‘in my world I reign supreme’, almost a parody of the Peer Gynt dramatist. Vordal we learn is wont to come to Borkman to have an audience for him reading his own tragedies, and in this scene, Borkman has just refused Foldal’s offer to pass the time’ in listening ‘to an act or two’ of his newest tragedy. Instead Borkman launches into his own favoured theme, his betrayal by the world and by one man in particular, who both sought something like a world to reign over too – as a government minister. Borkman laments his own fall from fortune, finding solace only in that his main rival never became a government minister either ( I quote below Frank McGuinness’s version of the play): [2]

The ‘fall’ of a great man is indeed a tragedy although Borkman jokes that it is not unlike the tragedies that Foldal himself writes – though ‘unspeakable’ in quite a different way . Though Foldal never does ‘get the joke’ against his writing intended by Borkman, the latter suddenly finds in his own situation some of the comedy that he has used to undermine Foldal’s pretensions as a tragedian. And why not – for there is in Borkman something of ‘men of the baser sort’, the working class miner turned banker but without the graces expected of that bourgeois status, and now ruined and living in a house he can’t own because he is legally bankrupt and subject to the exits and entrances of those who can remind him of his own base character in a number of ways.

There is no doubt that The Master Builder‘s hero too, Halvard Solness, is a man who might appear a tragic hero but has some of the quality too of a comic one, ‘in the way’ his story ‘is turning out now’ in the short time-span of the episodes of this drama. He too is a man not formally educated to his craft but who, like Ibsen, reaches a pinnacle of achievement in it and a man with lots of sexual secrets of the basest sort (the background of pedophilia (with the child Hilde Wangel) in The Master Builder is after all much more shocking than that of a teacher taking sexual,advantage of a college student (Mathilde) in Raicek’s ‘Me Too’ version of the play. And yet Ibsen intends his play to pastiche the tragic theme and hinge on a great man falling – literally from a tower of his own building. In early productions even the casting of Solness (it is after all a monumental part) played the great man card by putting in it a ‘great actor’

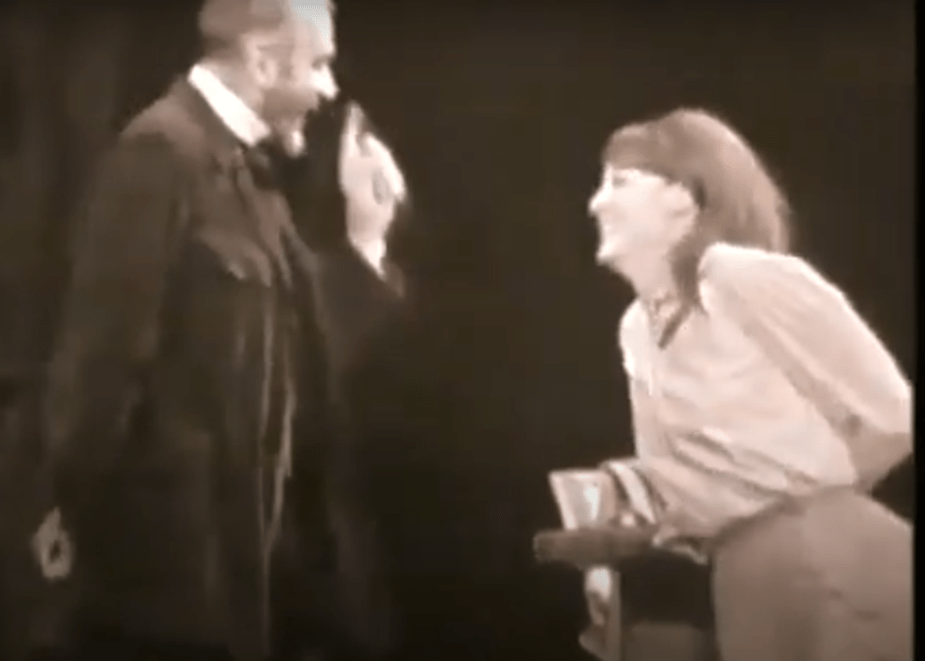

When I was aged 4 the role was played on BBC TV by Donald Wolfit (apparently the tape was wiped from the archive), then the most renowned of Shakespearean actors.

Likewise in 1966, I remember a class trip to see the role played by Sir Lawrence Olivier in The Royal Opera House in Manchester, where the part of Hilde (originally played by Maggie Smith – as in the photograph below) was then played by Joan Plowright

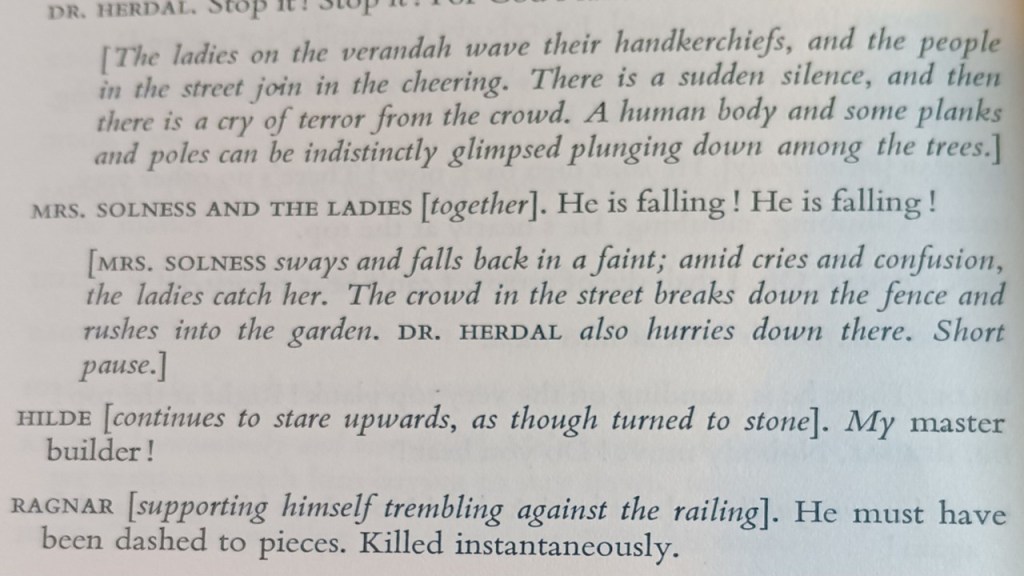

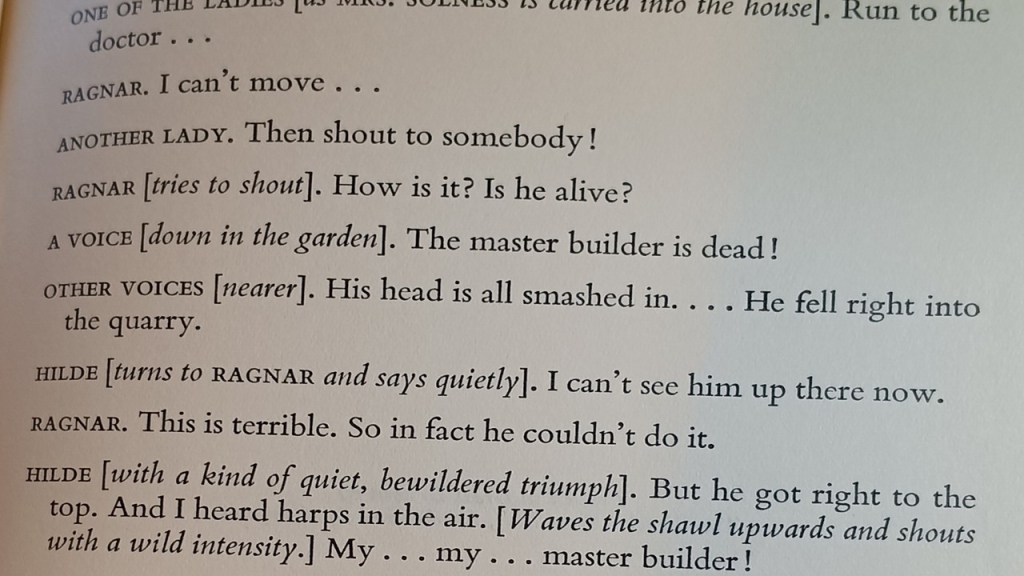

We almost assumed because of this that this play was a ‘tragedy’, about the ‘fall of a great man, but actually both of those productions maintained the high degree of comic misrecognition and coming together of lovers that has the pace of a comedy of sexual/romantic relations. When I read the play again last night (in James Walter McFarlane’s translation) , I wonder how much of the hysteria in the playing out of the literal fall from his own Tower of Babel of Solness at the end of the play was not intensely that of almost farcical comedy, so much so that directors convinced that this is transcendent tragedy miss out (as the BBC did) the business of the assembled ladies and their choric shock [3]:

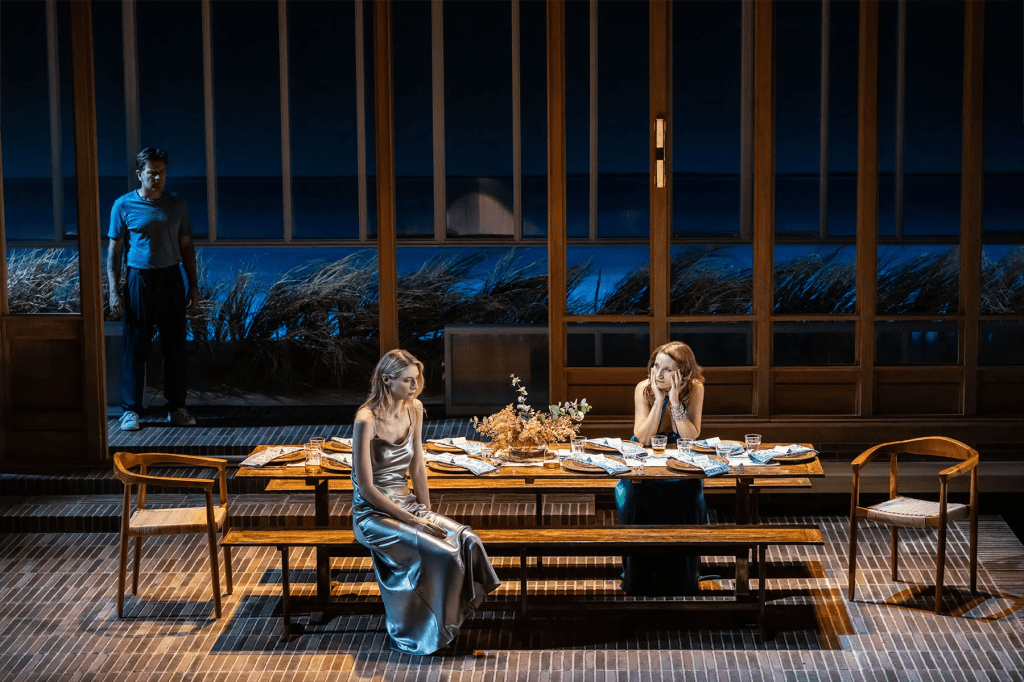

There is as much bathos here as can be engineered into such a short final moment of the play, and directors may feel that the screaming ladies, continuing to act out their distress would mask entirely the rapture of Hilde as she with death claims Solness as finally her own, and only hers: ‘My … my … master builder’. This last line has already used by Hilde to encourage Solness to climb the tower of his new home as, in order to plant a triumphant wreath of completion, he climbed the steeple of the church he built in the village of Hilde’s childhood and affirm not only his mastery but his iconic phallic masculinity. Raicek takes this apellation of Solness as the title of her version of the story, modernised and located in the luxurious setting of the Hamptons.

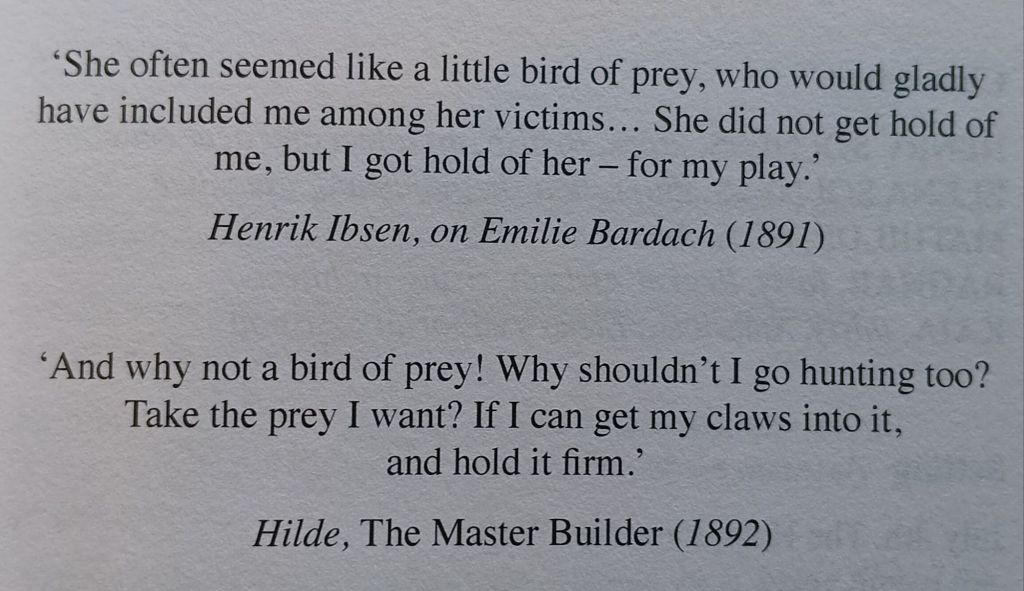

From the get go, the subject of sexual possession is the focus that Raicek clearly wants for her play: the translation of Ibsen’s line she quotes (perhaps her own translation or perhaps that of another) and quotes in a Note to the prefatory material; of the play is: “My – my master builder! Mine!’, and she relates this to the subtle forms in which male writers possess women of their acquaintance or more – as in those epigrams to her text:

Ibsen’s play on words above, if it survives translation into English, is a gift. If he escapes sexually powerful women (as from most of his plays you can see are plentiful- if only in his imagination perhaps, but perhaps not – and their ‘hold’ on them, he has a way of getting one over on them and holding them still – pinned down in art struggling like a moth under the pin of a lepidopterist. He can hold them inside his plays and his authority over them, but like trolls, they have a habit of escaping the hall of the mountain-king (and trolls matter in these plays too).

Raicek, on the other, now has the pen of the author and she determines to forefront male narcissism and inflated self-importance by even more undermining the significance of her Henry Solness’s tragic ‘fall’, ideally cast by using the more complicated sex-gender affiliations of Ewan McGregor, who publicly espouses that he is a feminist:

McGregor identifies as a feminist. In 2009, he said, “Women are always expected to be naked in films, but I like to try and do it so they are not naked—have the women not be naked. It’s a feminist thing that I do.” In 2017, he refused to appear on Piers Morgan‘s show after Morgan made disparaging remarks about the participants of the 2017 Women’s March. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ewan_McGregor]

The iconic phallic towers of modern architectural ‘art’ (her Solness IS an architect who has written books on the subject (like The Transgression of Architecture) though Ibsen’s master builder denies the term as applying to the over-educated) are seen here for what they are. Her Hilde references the tower blocks of Solness’ student now free of him as ‘a “cock block of a skyscraper”‘.[4] The women of My Master Builder are not only re-imagined to be less satisfied with the iconic images men make of themselves, they dominate the play’s men without even trying, especially the re-imagined Aline Solness with her yearning to build children – yet childless after her son’s death – and empathy with the destroyed and burned souls of girl-dolls (now a powerful Elena Solness, a ‘publishing executive’ with considerable power over the success of the fiction writing of Mathilde/Hilde who would have fucked Kafka, they in every way overshadow her men, even as literary typologies of the tragic. Whilst Ibsen’s Hilde still dreams of sex with Solness as the equivalent of his mounting a tower and looking down at her triumphantly from their tops, Raicek’s Hilde just ‘fucks him and left him for me to take care of’ as Elena puts it.[5] Speaking of her first husband ought to be a warning shot for Henry:

I liked feeling that my power over him was so intense … the only way he could assert his own was to possess me, to dominate me. [6]

Elena even has a consciousness of how her own female author has reformulated the womanhood of her characters, getting the manner of Aline Solness’s ‘fainting’ femininity (as in that last scene from Ibsen I cited above) just right though not capturing the degree of vulnerability of the girl-child Hilde who Solness preyed on – bending her over a desk to kiss her till interrupted by her still unknowing parents – for final year students, though vulnerable to predatory ‘professors’ may not be as vulnerable as a child is.

We want to believe that we are strong enough to assert control over our bodies, our destinies, our cunts. We can fuck like men, climb the ranks like men. we are not victims, no, we are not frail Victorian women! I was not the betrayed, childless wife, and you were not the groomed, exploited student. [7]

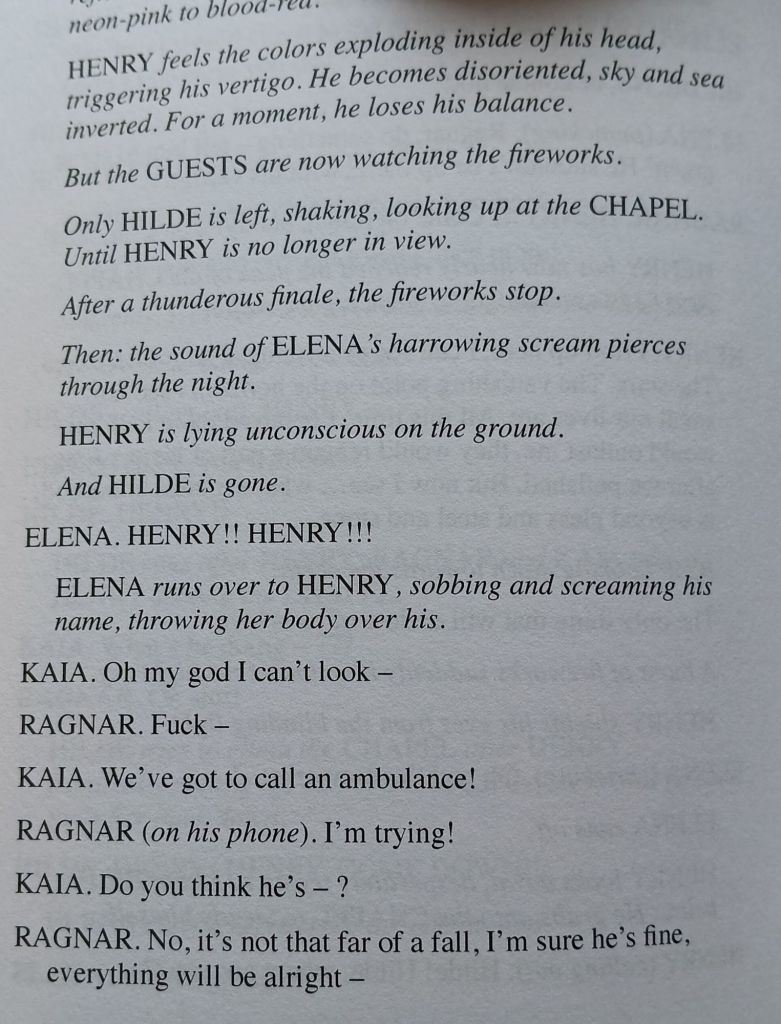

And this is not the ‘tragedy’ of the ‘fall’ of a great man but the usual kind of bloke for whom the power of a career as a ‘master’ is akin to sex/gender dominance, if only in their drams of climbing so high up both social and sexual conquest ladders. He doesn’t die, his head crushed in a fall even further into a quarry, as in Ibsen, but merelyfinally sees Hilde as a triumphant vision (how will they do this on stage?). [8]

But let’s leave it there. The final stage direction is ‘Blackout’. Is that Solness’s death or something more mundane – the end of the ‘tragic hero’ as a male forever and great men turned back into the baby in arms they often prefer to be. Did someone say: ‘Old fools are babes again’. That’s one way of seeing tragedy. Perhaps Goneril and Regan had a point about men who play at power.

Will report back after Tuesday.

With love

Steven

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_____________________________________

[1] Charles H. Reeves (1952: 172) ‘The Aristotelian Concept of the Tragic Hero’ in The American Journal of Philology Vol. 73, No. 2 (1952), pp. 172-188 (17 pages), published By The Johns Hopkins University Press https://doi.org/10.2307/291812 Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/291812

[2] Henrik Ibsen {in a version by Frank McGuinness} (2010: 56) John Gabriel Borkman London, Faber & Faber [with The Abbey Theatre, Dublin].

[3] Henrik Ibsen {translated by James Walter McFarlane} (1967: 88f.) The Master Builder London, Oxford University Press.

[4] Lila Raicek (2025:26] My Master Builder London, Nick Hern Books.

[5] ibid 78. The reference to fucking Kafka is ibid: 28

[6] ibid: 69

[7] ibid: 76

[8] ibid: 90f.

2 thoughts on “This is a blog in which I prepare to see Lila Raicek’s ‘My Master Builder’ on Tuesday 8th July at Wyndham’s Theatre, London.”