‘… the name dear me the name was the same it was Rose and under Rose was Willy and under Willy was Billie. / It made Rose feel very funny it really did’. [0] The Ethics of name-dropping and innuendo finding in Gertrude Stein’s (1939) The World Is Round London, B.T. Batsford Ltd.

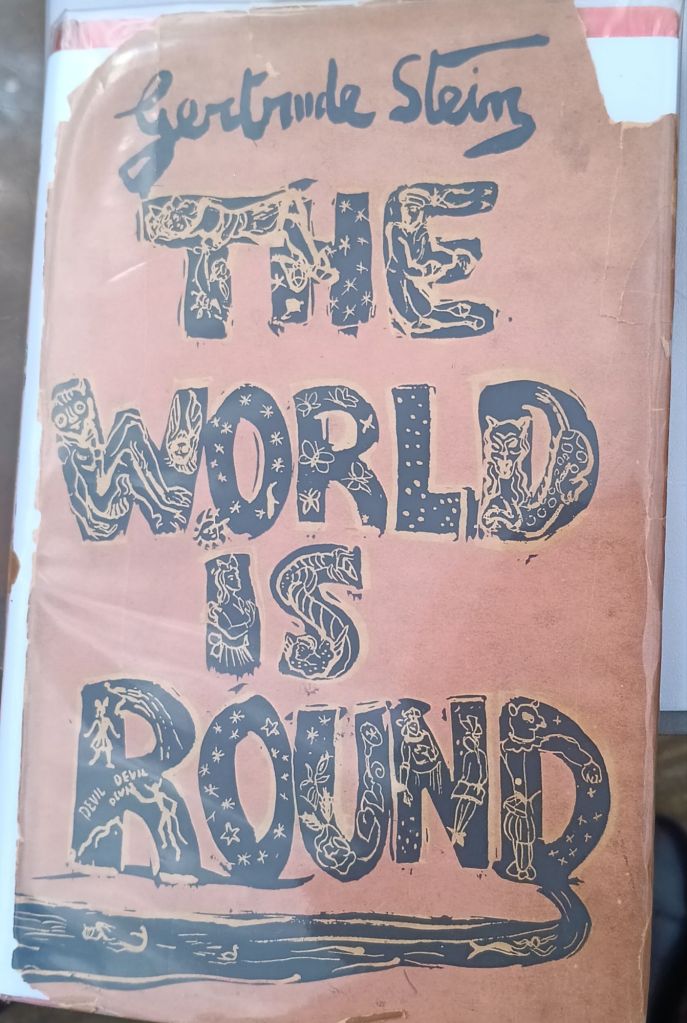

I have a rather damaged first UK edition of Gertrude Stein’s 1939 tale The World Is Round. It was illustrated by Francis Rose, the queer illustrator who was also the model (or so it is thought) of the 1930 painting (now in Edinburgh) Nude Boy In A Bedroom, a beautiful rear-view painting of a young man in a French hotel bedroom. Rose was also then a lover of the much desired Christopher Wood.

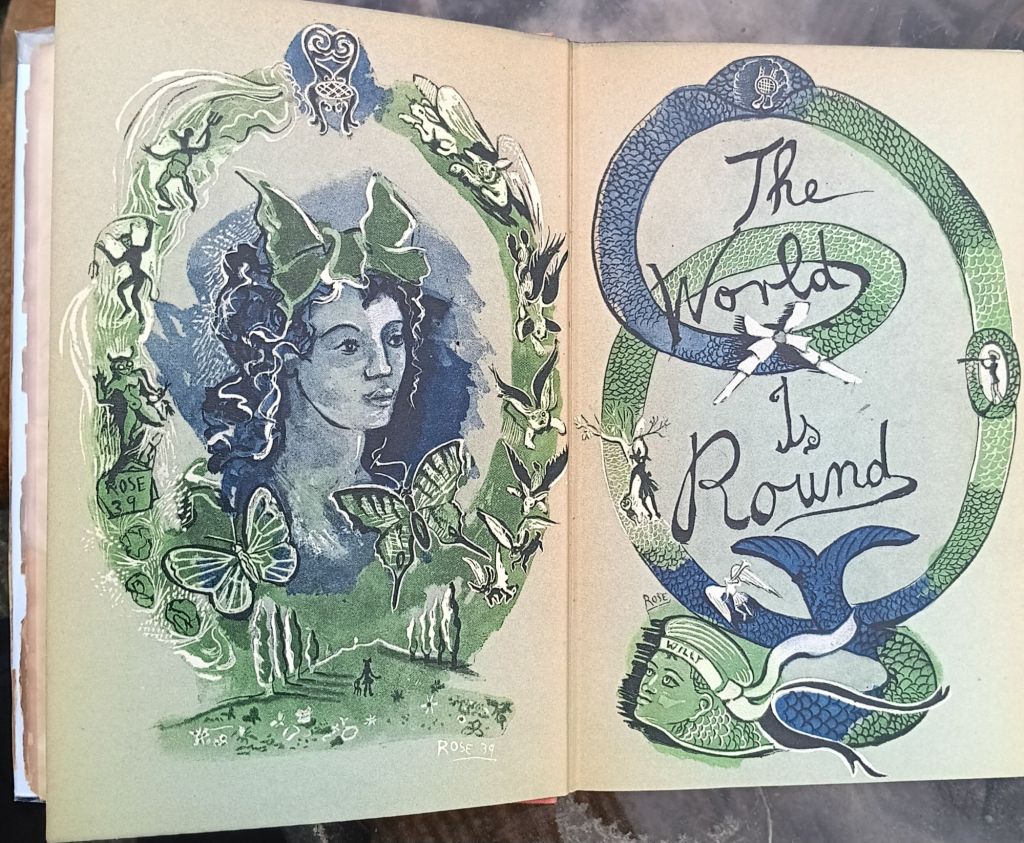

Stein remained a friend of Rose, who became Sir Francis Rose, up to her death. Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude’s ‘wife’ by virtue of naming by both, allowed him into her ‘Baby’s’ presence longer than many other men whom she distrusted as an influence on her beloved – Ernest Hemingway, for instance. There ought, one thinks, if this writer was not Gertrude Stein with her avowal of ’emotional association’ (or events events provocative of emotion – see my earlier blog at this link for the appropriate quotation) getting into her descriptions of the thing itself to be described, to be some story about this coupling of artist and writer. The story would speak of common queer, but also the individually distinct, sex/gender/sexuality threshold crossing and liminality that made up the events of their lives. Well I thought that might be so, but you can take contingencies too far, as I no doubt do in attempting to read more fully the double-paged half-title pages of the book so beautifully designed, in Baroque and/or Neo-Romantic style iconography, by Rose.

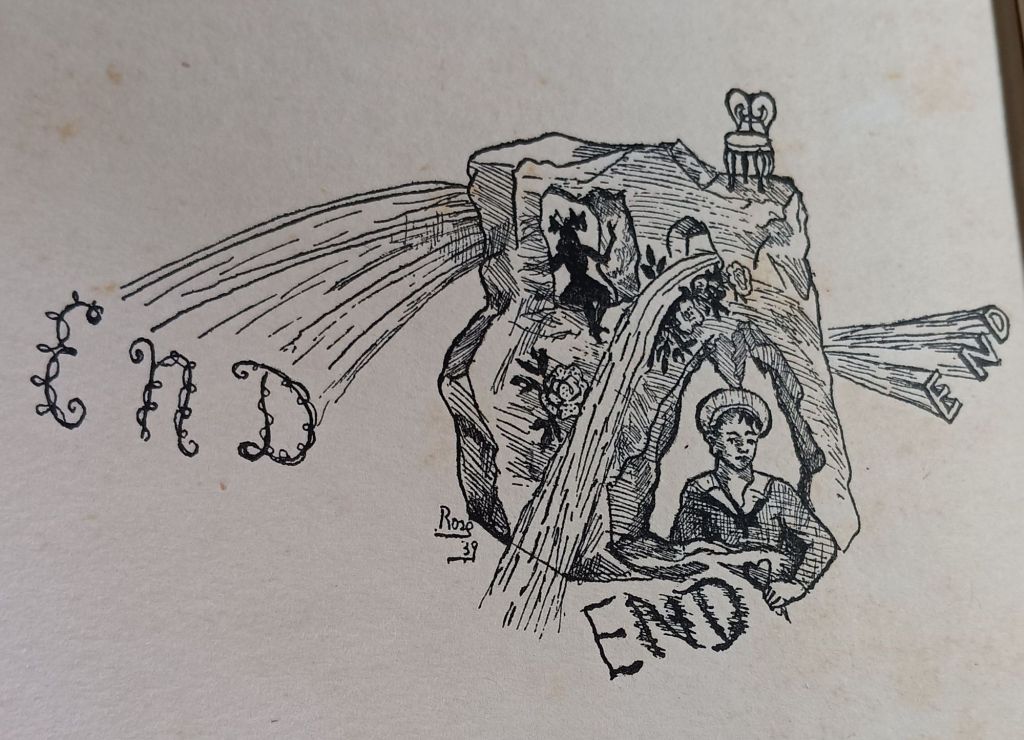

Willy, who in the book is most often represented as a sailor, appears as merman, gazing up at the picture of the character Rose on the page before. His head bears a cap, like a sailor’s cap, with his name on its head band – the name in bold font – written just in front of the point where the headband decides to play games, morphing behind him into repeated and proliferating swirls that create a shape that rhymes with the butterfly-shaped bow worn in Rose’s hair. I wondered why Rose herself did not have a name label, though doing so forced me to see the repetitions across the pages of the artist’s signature – simply using the name ‘Rose’ or ‘Rose 39’ to indicate the year of completion of the artwork.

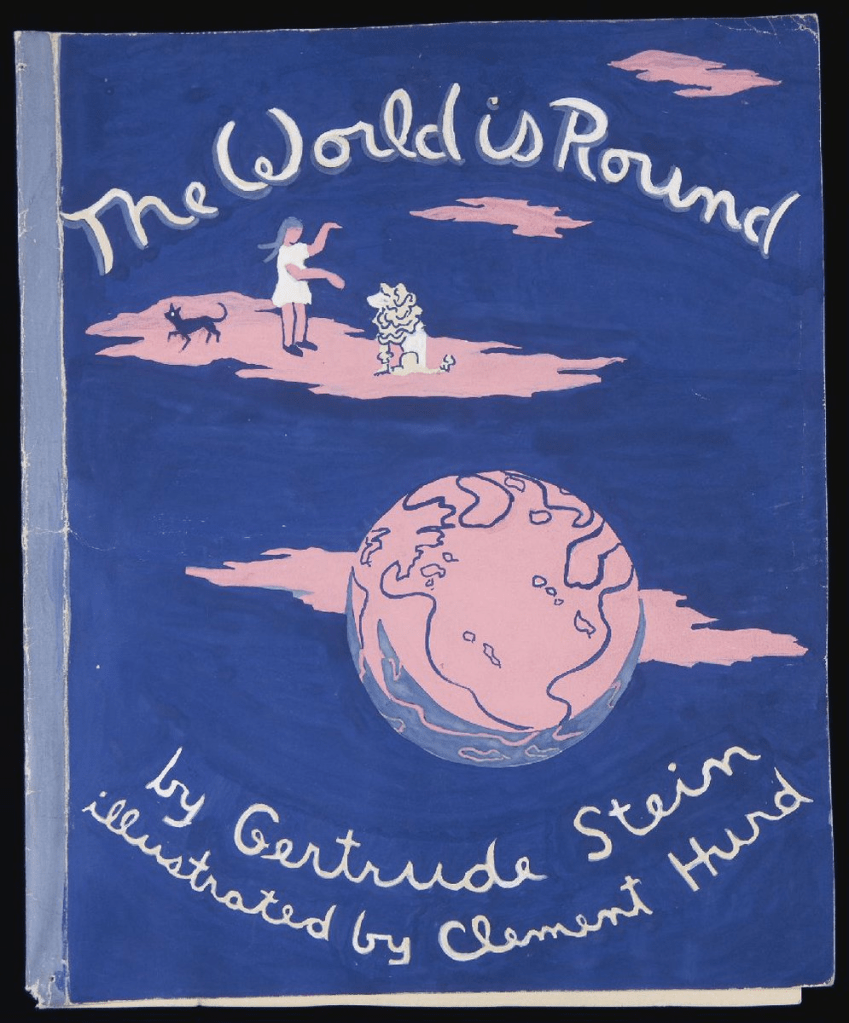

Did this constitute a kind of name-dropping and double reference that connected the verbal narrative art of Stein with the iconographic narratives in Rose’s illustrations? This is the ‘funny feeling’ that at least I had that I am going to try to follow up in this blog. One fact certainly stands against over-emphasising any dual parentage of the work between writer and visual artist. Published in the USA, also first in 1939, it was there illustrated by Clement Hurd. I have not seen this volume in full, except for pages excepted as photographs on the internet, of which I use two. The cover does not include a representation of Willy, but Willy is important.

At the opening of the book Rose sings ‘a song’ which questions not only the fit of her name to her experienced identity but also involves complex questions about the rightness of her sex/gender:

Why am I a little girl

And why is my name Rose

And when am I a little girl

And when is my name Rose

And where am I a little girl

And where is my name Rose

And which little girl am I am I the little girl named Rose which little girl named Rose [1]

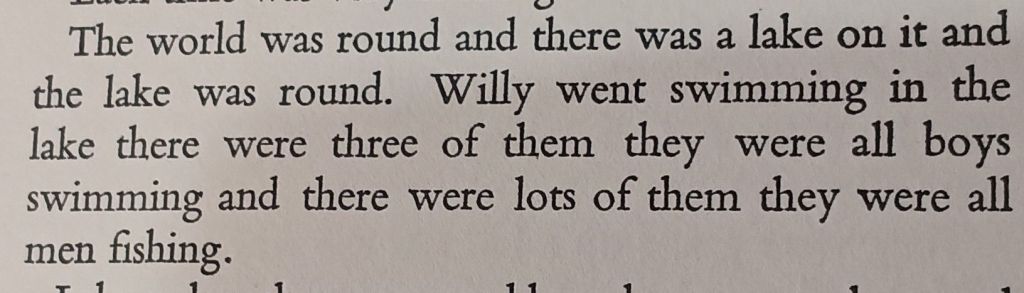

Why, when, and where personal identity and sex/gender status is marked in a person remain profound questions of our time, despite J.K. Rowling’s attempts to powerfully impose her view of things on all this with simplistic binaries. It is only a paragraph or so after this song that ‘a cousin named Willy’ is introduced, who though ‘almost drowned’ twice, seems to enjoy male power as his entitled context, for it is as expected to know that the lake we see him swimming in with other boys and surrounded only by ‘men fishing’ is ’round’ as we assert that the ‘world is round’. Male entitlement seems as natural as that. Men face dangers but save each other – Stein therefore enjoys the assonance between ’round’ and ‘drowned’: the assumed fact of the former ensures the contact between males that stops each other drowning: ‘And so Willy was not drowned although the lake and the world were both all round’. Surrounding danger is ‘a round / around’ shape nevertheless [2]:

Just after this point, we are told Willy has a song too, but his song uses his difference, whatever he thinks that is, not only to him but to all other boys, to assert his personal identity in such a way that its sex/gender status never becomes an issue:

My name is Willy I am not like Rose

I would be Willy whatever arose,

I would be Willy if Henry was my name

I would be Willy always Willy all the same.[3]

Sure, to the point of cocksure, one might say. The only thing Willy does fear is revealed in dreams of drowning in his own completeness of supposed surety: ‘Willy was asleep / And everything began to creep around / Willy turned in his sleep and murmured / Round drowned’. I find these things quite powerful as ideas that evoke emotion as if it might be merely the sensation of the words as a result of the assonance and rhyming that might achieve that effect. I can’t interpret them, but one thing is sure, it relates to the gendered construction of experience at many of the points at which it touches me.

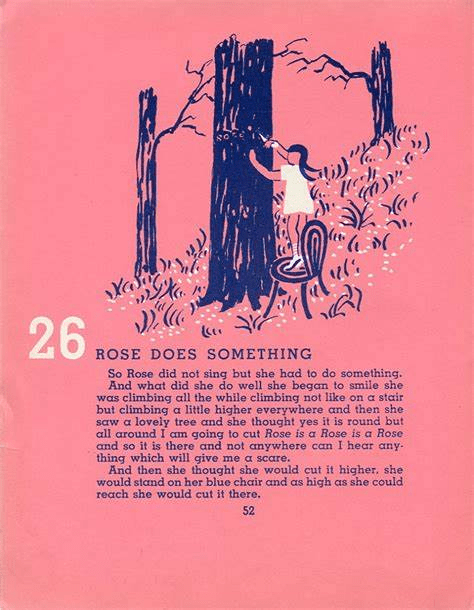

One chapter – Rose Does Something – certainly seems to give a key to Stein’s interest in gendered language and how radical ideas might be expressed. See below its opening in the USA edition.

The whole is about what it means to do something when that thing might be, for example, to write in a world where all roundness and completeness of the world seems solely designed for and the entitlement of men. Once she begins to cut her name it was clear that it must be cut high on a tree, that she must aid the deficits that she has and face the peril of failing to get all around the task: the whole is built in the harmonic ‘sound’ of words in assonance, rhyme and rhythmic waves of repetition.

… she would just stand on a chair and around and around even if there was very little sound she would carve on the tree Rose is a Rose is a Rose is a Rose is a Rose until it went all the way round. Suppose she said it would not go around but she knew it would go around.

The world helps boys to explore and master its own round a-roundness (the ability to be anywhere, even outside) , but girls must ‘make’ what does not exist – a space high even to be seen in a world not catering for them, and in doing so find in themselves their own complete a-roundness – even in the writing of the elements of her name: ‘carve and carve with care the curves of the Os and the Rs and Ss and Es in a Rose is a Rose is a Rose is a Rose’. [4] And here I find the beginning of my blog. Rose, so aspirant to carve her name, visibly, circumnavigates the tree and creates a world that is around about a round thing in sound, without us even hearing the patience with which she has to periodically dismount her chair, move her chair round, mount the chair again to reach the continuation of the line of her name carving and self-definition.

She finds, as if by accident, her name tops those of the two males of her past – one a boy (Willy), the other a lion (Billy) – but both put ‘under her’ in the hierarchy formed by the tree’s offering itself as writing space. Up high, she espies another tree – equally topped by the female name, the name itself not only of a flower but of generalised aspiration:

… she was cutting in the last Rose and just then well just then her eyes went on and they were round with wonder and alarm and her mouth was round and she had almost burst into a song because she saw on another tree over there that some one had been there and had carved a name and the name dear me the name was the same it was Rose and under Rose was Willy and under Willy was Billie.

It made Rose feel very funny it really did’. [5]

The shock of radical reorientation is one that proves that if you look around, not on the ground, you see others carving their aspirant names above those of males. It proves girls are able to command the whole round of things and get around like men do once they break through the ideology.

But was Francis Rose, who also had his own issues (pleasures and challenges) with sex/gender/sexuality being cast into the mix of things named Rose here? I think I believe he was and that this was something to do with Rose proving the very opposite of the joke that Margaret Thatcher made about the loss of her deputy Willie Whitelaw that:

If women can aspire high and contingently top male achievements, as Stein felt she did whatever the world thought of the superiority of male modernists like James Joyce (her bete noire) and T.S. Eliot over her as re-makers of literary language, then they do so only when they prove that even day and night, women can do without a willy – on them, in them, or presented to them. Francesca Wade unearths brilliantly one of the notes that Stein left behind after her death intended, or so Toklas thought anyway, only for her wife, and it is relevant here for it shows that Stein wanted Toklas to know she was complete with her – not only as a family base but as a sexual unit too: ‘I love her all night and I love her all day and every day and every night and in every which way’. [6]

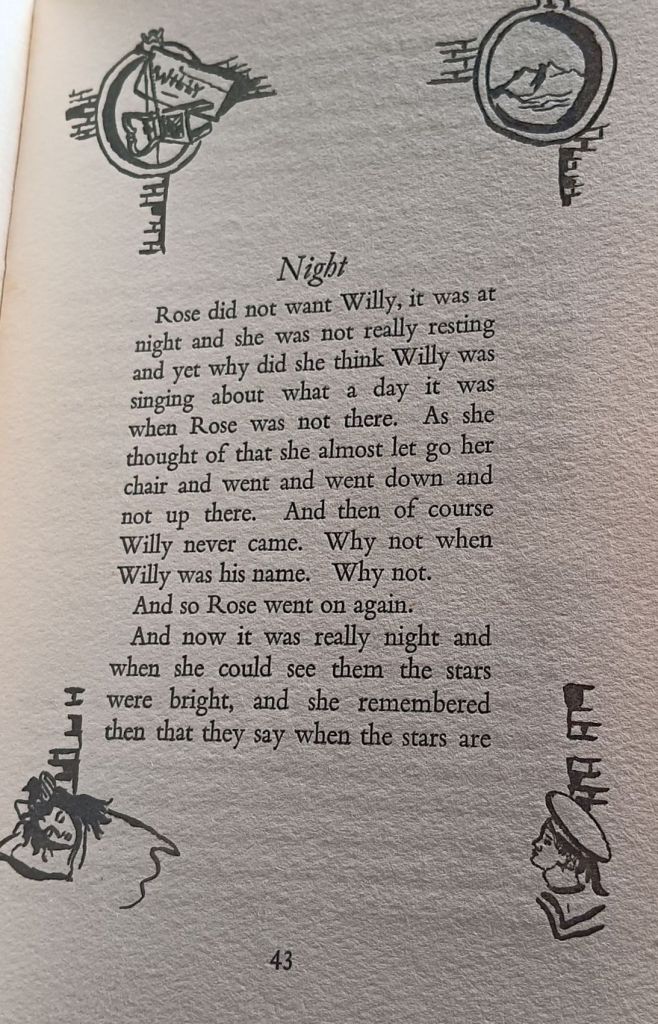

A woman who needs a man by night to make her feel sexually completed has, in one sense, failed to get around the problem of male claims to necessary entitlement that are traced to biological imperative. I think this is what Stein’s perception leads us to. In The World Is Round , which tries to scope the experience of both Rose and Willy at night (or in the night) as much by day (or in the day) the little subsection Night has – together with its marginal illustrations (one per corner of a text that is justified in a reduced central space of the white page) – seemed to suddenly extend in order to show that Stein’s radicalism was a queer radicalism that starts off directly (‘Rose did not want Willy, …’) – one that queered gender/sex, as well as other norms. Well, at least I read it thus:

bright rain comes right away and she knew it the rain would not hurt the chair but she would not like it to be all slimy there. Oh dear oh dear where was that dwarf man, it is so easy to believe whatever they say when you are all alone and so far away. [6]

And we need to extend the quotation onto the next page (as I have done in the last quotation} to see how viscerally Stein imagines this – even allowing (despite her theory of avoiding emotion by association – a little disgust to creep in about the supposed need of women for men. Are there not advantages, it seems to say, in avoiding the sensation of it being ‘all slimy there’? There is no reason, after all, why Rose needs to be as conflicted in this paragraph as she ‘was not really resting’ to fill that restlessness with Willy. Francis Rose is perhaps self-implicated in his drawings. He draws sailor Willy as if his longing were a thing he thinks it natural for Rose to return, but Willy on this page is isolated. In the two top pictures with two porthole like windows opening a round hole in a brick wall of straight lines Rose’s blue chair – that she climbs trees and mountains with – is set in the porthole on the left at a contradictory angle to Willy’s name, as if the chair might be a better alternative for Rose than Willy. The porthole on the right looks out on the mountain that Rose will eventually climb, leaving wet waterfalls behind (and below these Willy too) .

This won’t be everyone’s Gertrude Stein but I think it is her for me.

All for now

With love Steven

xxxxxxxxx

______________________________

[0] Gertrude Stein (1939: 51) The World Is Round London, B.T. Batsford Ltd.

[1] Gertrude Stein (1939: 8) The World Is Round London, B.T. Batsford Ltd.

[2] ibid: 9

[3] ibid: 11

[4] ibid: 50 – 51

[5] ibid: 51

[6] Stein Cited by Francesca Wade (2025: 234) Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife London, Faber.

[7] Gertrude Stein (1939: 43 – 44) The World Is Round London, B.T. Batsford Ltd.

One thought on “‘… the name dear me the name was the same it was Rose and under Rose was Willy and under Willy was Billie. / It made Rose feel very funny it really did’. The propriety and ethics of name-dropping (and innuendo finding) in Gertrude Stein’s (1939) ‘The World Is Round’ London, B.T. Batsford Ltd.”