It would be: ‘He tried to notice the underlying things!’ Is this a case in point: This blog looks at a discovered copy of the 75th anniversary issue of ‘Granta’ from 1964 [Volume 68, No 1233]. In it a poet speaks of another much earlier poet: ‘Going, he carefully left his words behind’.

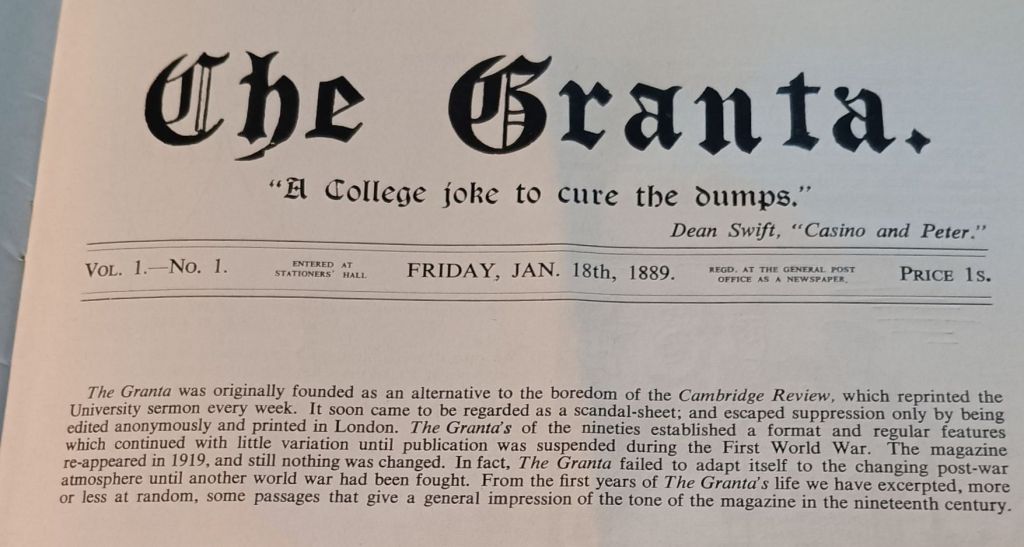

My husband Geoff is a bibliophile and is always on the lookout for bits and pieces of literary history that he knows will appeal to me. Recently, he brought home this rather special issue of a magazine with a long history and role in the mediation of artists developed within the institutional academic system, confined here entirely to Cambridge University. Wikipedia has the history of Granta, which explains the rather wonderful reproduction of the cover page of the 1889 first issue, which preface some very silly extracts from its early history. Wikipedia says:

Granta was founded in 1889 by students at Cambridge University as The Granta, edited by R. C. Lehmann (who later became a major contributor to Punch). It was started as a periodical featuring student politics, badinage and literary efforts. The title was taken from the River Granta, the medieval name for the Cam, the river that runs through the city but is now used only for that river’s upper reaches. An early editor of the magazine was R. P. Keigwin, the English cricketer and Danish scholar; in 1912–13, the editor was poet, writer and reviewer Edward Shanks.[6]

In this form, the magazine had a long and distinguished history. The magazine published juvenilia of a number of writers who later became well known: Geoffrey Gorer, William Empson,[7] Michael Frayn, Ted Hughes, A. A. Milne,[8] Sylvia Plath, Bertram Fletcher Robinson, John Simpson, and Stevie Smith.

In 1964, at the time of this 75th anniversary issue, the editor was the now retired literary academic John Barrell. The issue was intended, after its series of silly excerpts from its own early history, an anthology of pieces of writing by writers already better known than they were when published, as Cambridge students. These include Thom Gunn, from whose contribution to the magazine, a poem called Elizabeth Barrett Barrett, I take my title quotation, of which more later.

The names otherwise represented were even more August, perhaps mostvtellingly so E. M. Forster, though his contribution is not a piece that one would desire to survive in order to represent the writer, being a piece of nonsense about the conversation between different classes of boats imagined to sail the Cam along the ‘Backs’, that stretch of the river running behind the major colleges on its banks, especially King’s and Trinity College. It’s a trite piece, worthy only of a footnote to Forster’s achievement or the history of this closed community with its silly in-jokes.

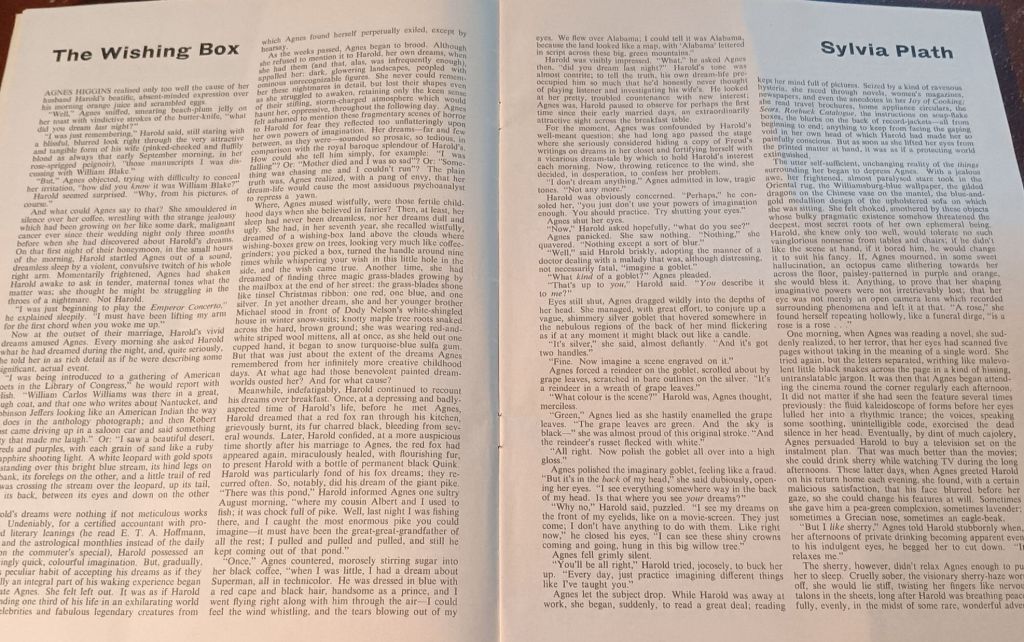

Other pieces are interesting, either because, in one case – that of Ted Hughes, they represent the quality of his entire work or because they are interesting biographically if not as self-justifying good literary works, like the story The Wishing Box, by Sylvia Plath.

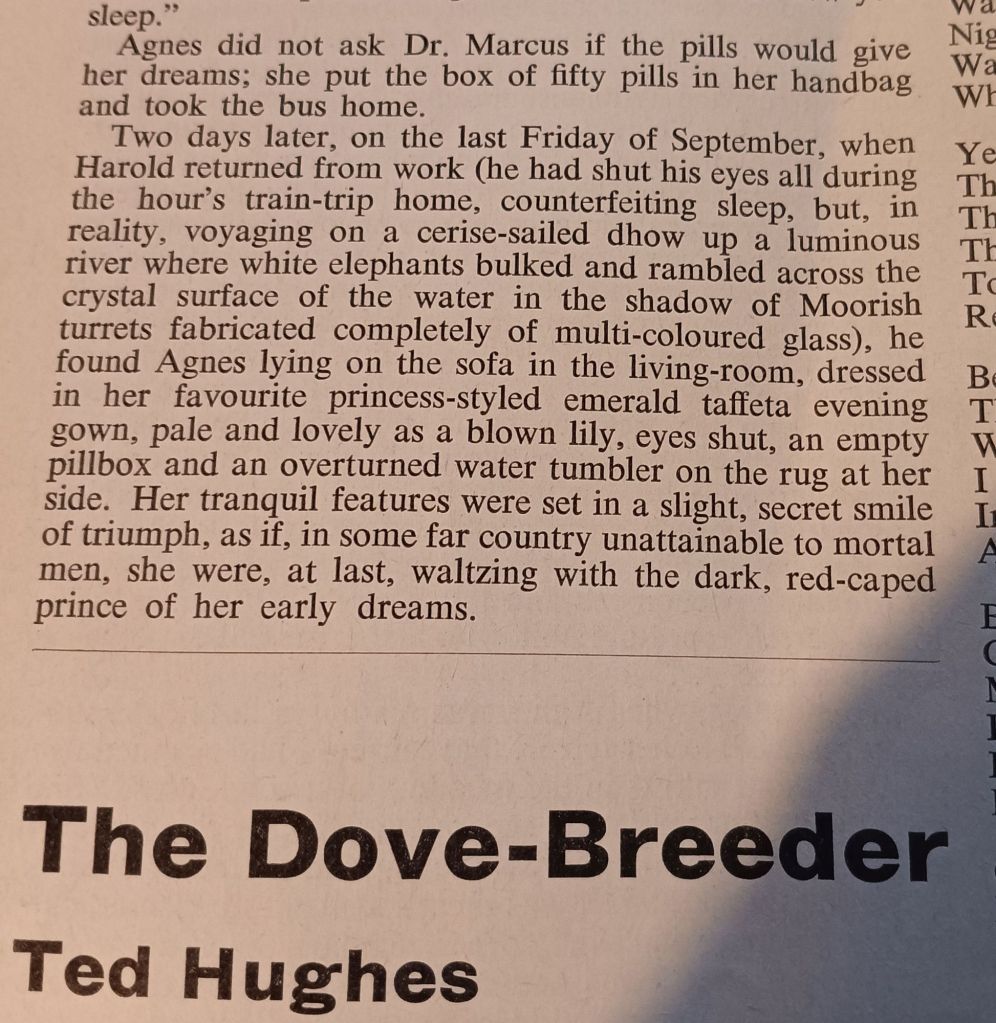

It isn’t a great story and a long way from the innovative and mature prose of The Bell Jar, but as a piece of writing about the folk psychology of suicidality and suicide, it is intriguing, if rather grimly so in a piece that presses upon the next contribution, Ted Hughes’ The Dove-Breeder, about a gentle man (as gentle as the doves he breeds) who finds love forces him to come to terms with what is ferocious in what he carries into the world of himself:

Love struck into his life

Like a hawk into a dovecote.

What a cry went up!

...

Yet he soon dried his tears

Now he rides the morning mist

With a big-eyed hawk on his fist.

Plath’s story is a kind of mirror image of that poem’s story about a woman named Agnes, married to Harold who even dreams lucidly about his literary celebrity. She is torn nightly by the brooding violent darkness of her own dreams, of which she retained on waking:

… only the keen sense of their stifling, storm- charged atmosphere which would haunt her, oppressive through the following day. Agnes felt ashamed to mention these fragmentary scenes of horror to Harold for fear they reflected too unflattering upon her own powers of imagination.

It is an engaging story but nevertheless Harold and Agnes seem to represent a simplistic allegory rather than having a recognisable basis as a believable story of actual lived lives: a coupling of two kinds of conditions under which sages of creative imagination thrive on the one hand or fail on the other. In the story, Harold is self-entitled by masculine training and social power, Agnes’ creative power is refused recognition and dissipated in the world constructed it appears to constrain women.

Plath’s allegory is accurate, but too focused around the explanation of Agnes’ suicide to seem other than another instance of a fragmentary scene ‘of horror’. Yet suicide is made glorious in this story: as the only way Agnes can gain precedence as a maker of performative signals of human significance over Harold and represent the horror of her own fragmented imagination.

Agnes makes a beautiful if fantastical picture in her death by sleeping-tablets, as a kind of latter-day Lady of Shallot. She certainly further diminishes her husband’s pretension to specialness and imperious power. And then the editor places next to the end of the story Ted Hughes’ poem. We are obviously asked to see the autobiographical relevance: Plath committed suicide on 11 February 1963, about a year before this story, and Hughes’ poem were both republished in this edition of Granta.

Yet we have to ask what kind of literary culture looks for this view of what writing might be and takes a shot at its survival in this context of what was revival.of seemingly ‘predictive’ juvenilia produced by people who were now literary celebrities. At this time many feminists openly blamed Ted Hughes for prompting Plath’s death. We’re they as undergraduates fed fuel for that reading by Granta.

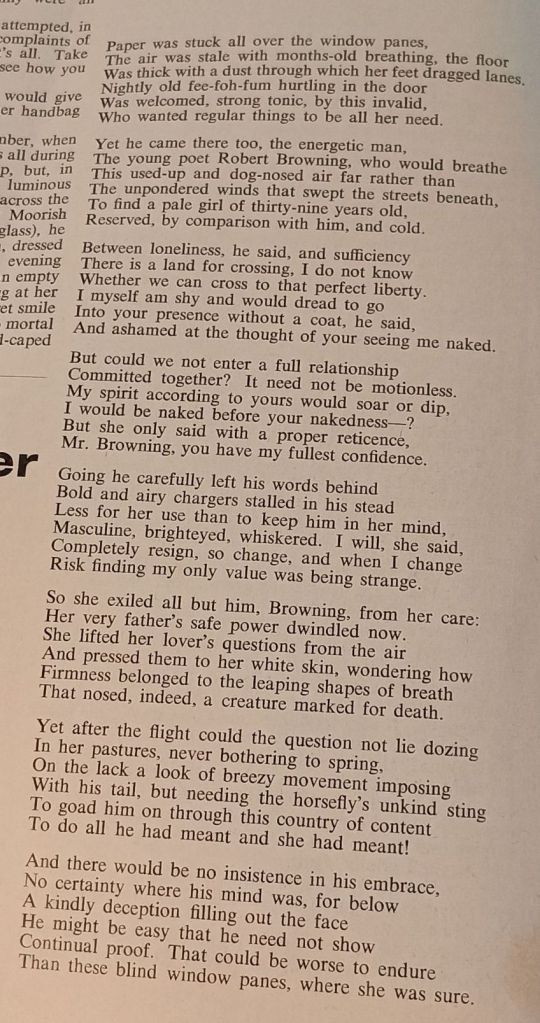

There are other pieces, that also lack the air of good writing, by then celebrities: A.A. Milne, Roland Firbank, Michael Frayn, and Stevie Smith. None of these contributions strike me as lost masterpieces. But one holds my attention: the poem by Thom Gunn, Elizabeth Barrett Barrett. The line I quote in my title seems a great epigram for the project that was this issue of Granta, in which so many writers ‘on the go’ either to celebrity or later oblivion ‘carefully left (their) words behind’

I am not knowledgeable about Thom Gunn ( though I wrote a blog on him nevertheless: at this link) and my sense of this poem us somewhat shaped by the fact that I can not find it in his extant Collected Poems, though no doubt if lurks in scholarly collections somewhere. Yet why did Gunn choose to write about this poet using her less well-known name before she was married? The poem follows on from the pieces by Plath and Hughes and I am tempted to equate the contrast between the men in Elizabeth Barrett Barrett’s consciousness [let’s call her EBB henceforth) is depicted in the poem with the stuff of Agnes’ dreams in Plath’s story: ‘dark flowering landscapes, peopled with ominous unrecognisable figures’. Just as in Plath, these figures resolve into Fathers and unexpected bold suitors. Some fathers frighten whilst they reassure, and abuse in both fumctions:

⁸Nightly old fee-foh-fum hurtling in the door

Was welcomed, strong tonic, by this invalid,

Who wanted regular things to be all her need.

Yet he came there too, the energetic man,

The young poet Robert Browning, ...

Robert, like Ted, allows the female poet to say she will:

Completely resign, so change, and when I change

Risk finding my only value was being strange.

EBB’s dilemma was that resigning herself to Robert Browning was a resignation of her claim to poetic independence as a woman and a considerably better known one than the young Browning. Would that reveal that her only ‘value’ was in being outside the norm,’being strange’? And would she really ever be sure that giving the world up for the sexual and romantic love previously denied, really gave her what she needed, proof of her value?

And there would be no insistence in his embrace,

No certainty, where his mind was, for below

A kindly deception filling out the face

He might be easy that he need not show

Continual proof. That could be worse to endure

Than those blind window panes, where she was sure.

Inside her room, breathing its stale air alone and constrained to move through dust ‘through which her feel dragged lanes’, she could shut out any recognition of the world’s refusal of value by blinding its eyes upon it, it’s window panes, with paper. Thus was the effect of her poetry in providing a pretext for unwomanly strangeness. But Robert would expose her to the need for validation by any other measures, her verses given up in support of his energetic poetry.

Tne analogy with Plath and Hughes is there, I think. And though this is pure speculation, how interesting a speculation about cultural artefacts otherwise buried. Granta was a magazine upon which, like the river that word once named, tragic things things better committed to its depths might float. Even at the time, advertisers in the real world saw it as a means of access to graduating people stepping out into high-flying but very ordinary jobs, ready to prove that burning the midnight oil was worth it, as implied in this recruitment advertisement for a construction company. Those readers of Granta, the company hoped, would set their value and that of the education they gained in the job market, in what Thomas Carlyle called the Cash Nexus of determining the value of persons.

This is the world assumed by all the advertisers who kept Granta going, a world of worldly and income hungry punters who under their campery and pretension, have a cool head for business. My favourite advert for Midland Bank has Oberon, the King of Fairies, and a fairy still, realising that ‘a bank of wild thyme’ that sustains him in ‘a midsummer night’s dream’ is less useful than the solid and dependable bank that was the Midland – though even that bank too now has flown in the wind with the thyme / time, long absorbed by global capital under the title HSBC.

For poets and other literary artists, however, male, female, or fairy, the value they sought was to be remembered in their writing. EBB gave that up in the promise made by Browning that he would be ‘naked before your nakedness’, though he meant the exposure of their true selves to each other not their bodies. However, did he mean both?

Her poetry began to fade from public memory as his soared, despite Aurora Leigh. This was the issue for Agnes too subliminally in The Wishing Box, and would have been understood by Plath even as she married her own ‘energetic man’. In the end do both female poets realise that the men in line were selfish of their own reputation and immortality not that of their wives because: ‘‘Going, he carefully left his words behind’. However speculation is no more than that, so let that be an end.

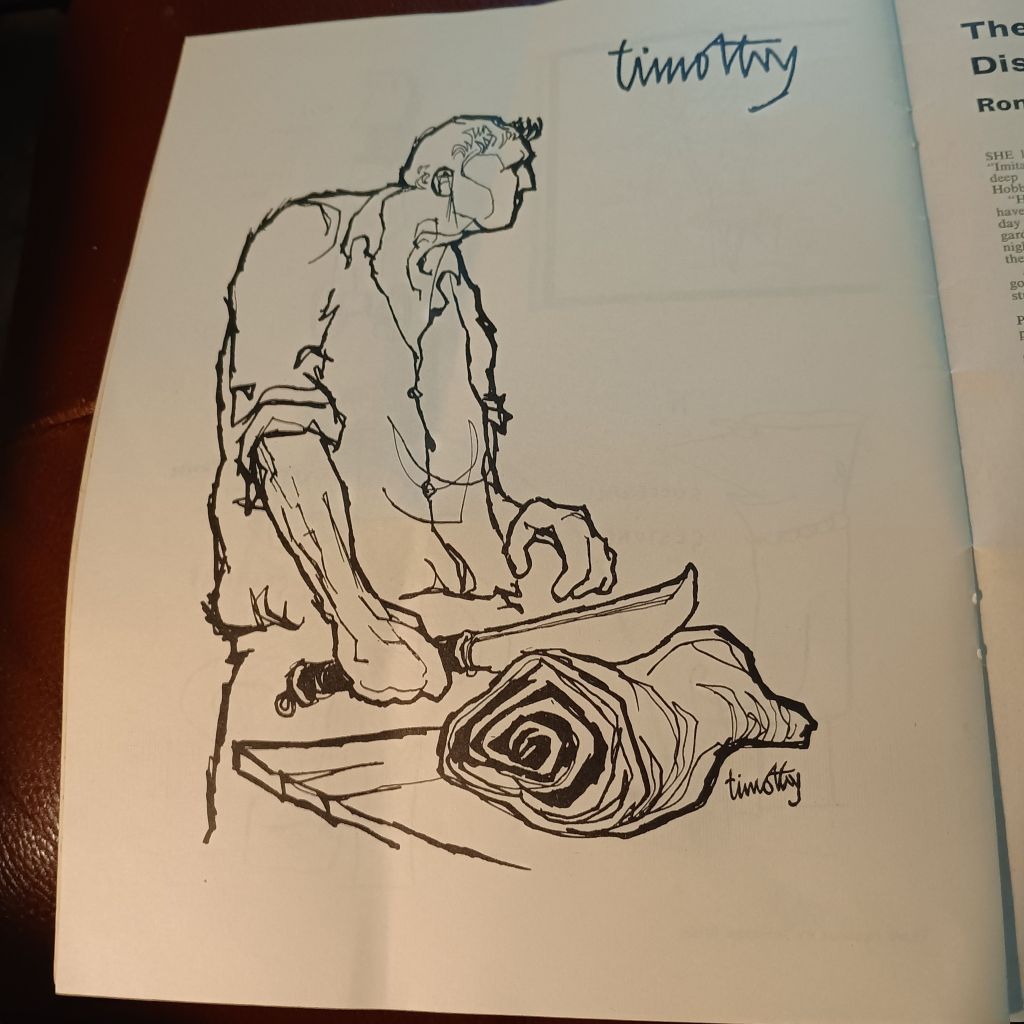

Well except for a contribution of a drawing selected for this Granta, its artist, being dead, which also intrigues me.

Tmothy Birdsall is an interesting character who left Cambridge to draw politicslly satiric cartoons for The Sunday Times and latterly Private Eye, also working with the That Was The Week That Was team with David Frost. He died of leukaemia at age 27 in 1963 before this publication. I can’t discount that this drawing is not political satire, though of whom I would be pushed to say. Moreover, it doesn’t feel like a satirical drawing, even though it is as brutal as that that genre.It is brutal because it represents a kind of masculinity that seems so unlike the student population of Cambridge.

It is a working man with huge hands and a smaller head proportionally, using manual strength to cut through the meat and bone of an animal leg. His body and dress lacks every feature of the classical male that traditionally marked artistic beauty as the academic tradition valued it – even shown in the the ugly hang of his shirt over his belly. The drawing emphasises muscle and sinew in tense lines though. What was the purpose of this drawing and why did the editors re-select it? Now there’s a mystery!

Have I ‘tried to notice the underlying things?’

That’s all,

Love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx