I am returning to WordPress blogging after a break, including a short break in Amsterdam, which I will no doubt make many blogs about in the near future. But I, like the wedding guest in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, felt that my taking leave of WordPress was not unlike his.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

And am merely hoping that I will also on the ‘morrow morn’ rise:

A sadder and a wiser man,

Maybe both sadness and wisdom are relative to each other. I took my leave aware that I had been trapped in a numbers game of my own choosing, not unlike that described by John Rechy in his novel of a numerical queer life, Numbers, except that the obsession with numbers was for me based on compulsive commitment to daily blog-writing rather than to unregulated accumulation of sexual ‘tricks’ with men, sought out in public places. I wrote it up in the blog at this link. The sadness came with the realisation that my attempt to maintain a continuing rising record of daily blogs was a kind of obsessive compulsion aimed at an using an inappropriate means to regulate my emotional, cognitive and sentient life. The wisdom comes from knowing that though I need to write and probably daily, I do not need ever to complete a piece I write, even notionally so that it becomes a single unit score in a continuum of daily rising scores collected digitally and with all the hallmarks of a misunderstood compulsion. I can keep writing to any piece that continues to interest me and then send it out for better or worst just to prove to myself that I have sat and thought over mulled life experience – be it book, film, theatre or less easily classifiable trip away.

But today’s start overlays one I am preparing on Heather Christle’s amazing new book In The Rhododendrons that still awaits the moment of feeling comprehensive enough to summarise what I felt about this amazing book, especially since I only took to it because it was recommended by Kaveh Akbar and because he makes an appearance or twio within its semi-autobiographical pages. It never will be comprehensive in the light of that ambition but it will I hope be ‘good enough’.

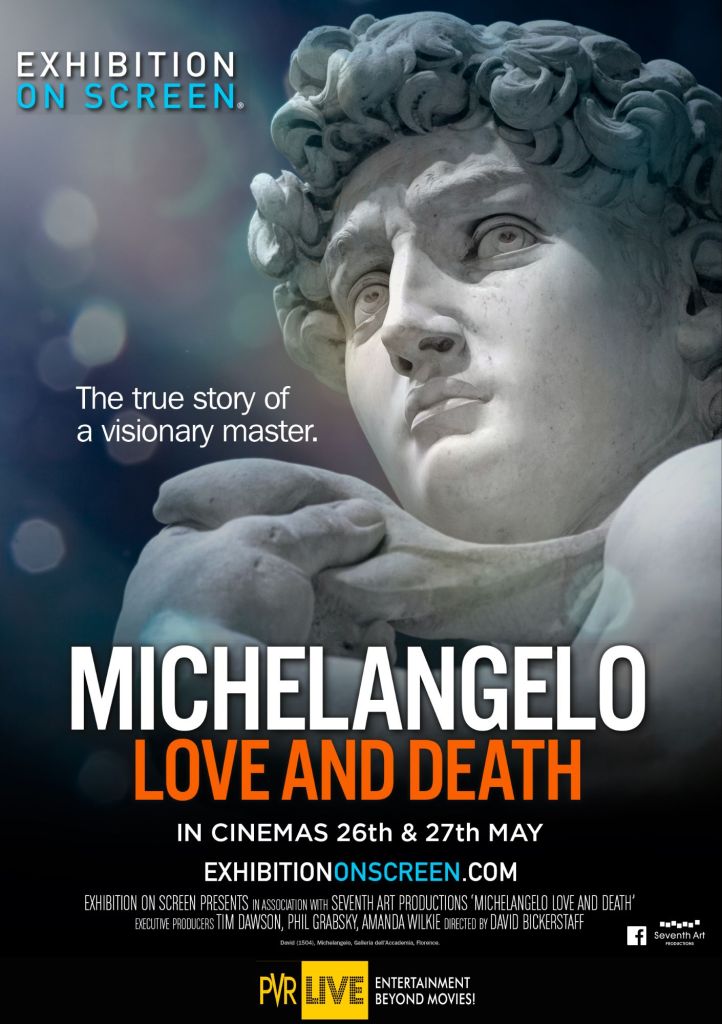

Tonight I see the new film from Exhibition on Film on the work of Michelangelo, grandly subtitled Love and Death. Maybe Love and Death interact somewhat like sadness and wisdom, being often both involved in both massively complicated experiences> I want to see though how the film justifies this confrontation with Eros and Thanatos . Let is hope it is not by making them binary values (and thus opposed to each other) as some simpler-minded explanations make them (as in this link). Anything could be expected of a film describing itself in its literature as a ‘true story of a visionary master‘, which is a noun phrase as full of problematic terms as you could ever imagine possible. Even if ‘truth’ will not be delivered, except in a thin form of that word, as might be expected, then the mastery of the condition of ‘being visionary’ will hardly be possible to demonstrate, since ‘vision’ is both too limited and too reductive to really describe those attainments, either as ascribed to Michelangelo or as descriptive of the meaning of the coming together of forces we label as ‘love’ and ‘death’ respectively. However, these terms all do come to mind before I go in thinking of the artist’s Madonna della Pietà, ‘in Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, for which it was made’, in Wikipedia’s words.

But at this point, I broke off to get ready to go to Bishop Auckland Town Hall, where Geoff and I had tickets for the front row. Now it is the day after and I have reflected on a film with the usual strong qualities of David Bickerstaff’s direction that has benefited from not being about a particular exhibition (for my blog on another Bickerstaff film – that one on a Lucian Freud exhibition – see this link). On seeing it I think you need to cast any expectations related to anything like an examination of either Eros and Thanatos or Love and Death in any way that consults depth psychology of any school. The most comment on these themes was vaguely gestural – in a way that had the backing of a fine historically precise and respectful-of-period-values biography behind it in Martin Gayford’s contributions to the film, and a great deal of the same vanity and theoretical imprecision – about both sexuality and art – in Jonathan Jones as in his very skewed and egoistical newspaper art criticism ( I admit I have not read his book on the Renaissance and am unlikely to do so).

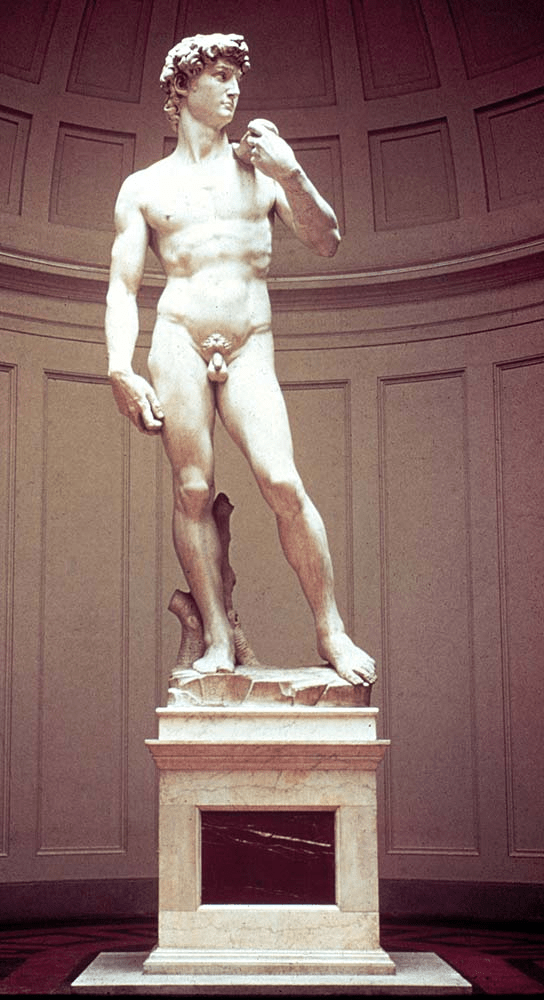

Jones’ insistence on Michelangelo being ‘gay’ gets us nowhere for the term has no hooks in the period, and certainly not to the ways in which love and death are signaled in the art work, for their is little value in his plodding explaining of Michelangelo’s undoubted debt to Neo-Platonism, a debt that, as he rightly says, was current behind the cognition of art and the body across the Italian late Middle Ages and Renaissance. For to say that looking for the divine in male beauty is an excuse for his depiction of the male body gets us precisely nowhere, and certainly fails to help with the strange contradictions in the depiction of male beauty in both Michelangelo’s Bacchus and especially that masterpiece of queer disproportionate-parts-to-the-whole that is David, with (for example) the huge disproportion of the queerly sexualised hands to those of the slight body. Not only beauty but the yearning to be touched and to touch need no excuse from Neo-Platonism, for that school of thought nearly always explains away both of those passionate experiences, as much in Bernini as Michelangelo.

Otherwise the commentaries by experts fitted better with Gayford than Jones – for they were either precise bits of connoiseurial judgement-making (but of a high order of ‘noticing’ what matters in the general mode of an artist’s ‘tics’) or useful in sharing insights from other domains of knowledge – like the academic anatomist’s comments on the accuracy of the bodies tensions in mid-point of some mobile action to the underlying muscle structures.

Better still the artist who commented on Madonna della Pietà, lauding the disproportionate vastness of the body of the Mother Church Madonna that enfolds and secretes into the landscape chasms and caverns that its dressed form makes, while still representing in the face of the Madonna the face of a very young girl – quite unlike the motherly body below it, and yet bound to that body by virtue of its own veiling.

And then that artists’s notice of the fingers that do not just hold and contain the corpse of a son but probe his atrocious wounds on the side of his bodies as if it was important not only to touch but learn thereby better how to know his passion. The artist read that as on of many signs to viewers to understand the pull in any great plastic art to invitations to fell the work, if not with embodied than the cognitivised sensation of embodied fingers.

And therein lies the true connection in Michelangelo between love and death: Passion. For Passion (from the term passio – I suffer or experience) is an act of active knowing that occurs in apparent passivity and it links or human responses to those great themes of love and death, where actions of loss and gain are all felt to progress inwardly to and in the body – if shown, shown only in the flexion of interior viscera and muscle. We yearn to feel the body that is the absence and presence of the lost son, just as we do the body of the loved one, and the yearning is still embodied but still not quite mutually physical

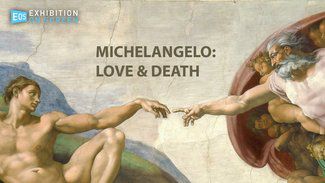

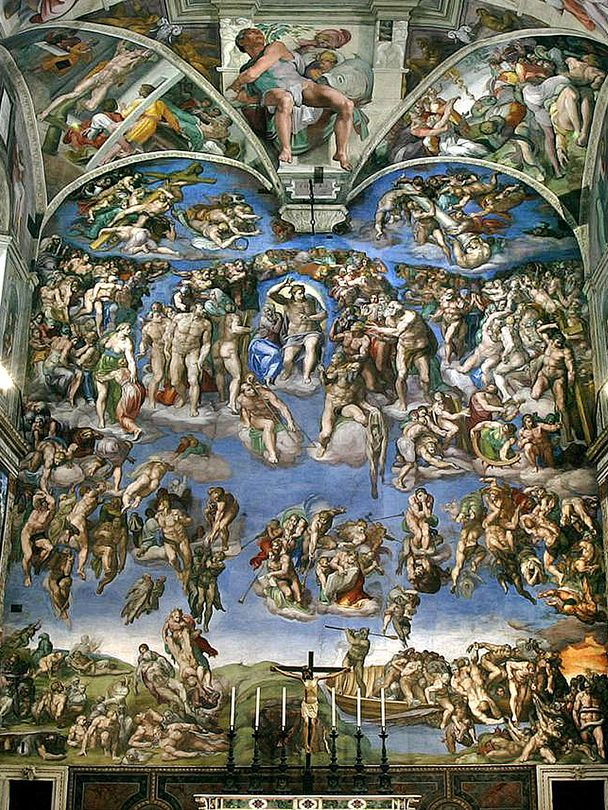

As one commentator put it, the ceiling of the Sistine chapel centres on a touch that never happens – and that shows the love of God the Papa and his holy community for archetypal man – the gorgeously muscled Adam:

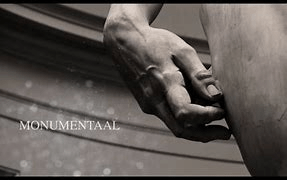

And then you notice those fingers of that huge hand of David vicariously for thus both touching and reaching his own thigh:

It’s monumental! Yes. But it is also ‘touching’ in a way we rarely associate with monumentalism. Saint Peter’s Basilica is monumental but Michelangelo’s figurative art yeard not only to the three-dimensional but the condition of the unframed art work. And that the Curator at the Vatican says is what the late work we know as The Last Judgement is – a hole blown by unframed art covering the whole wall with nudes. However even small spaces in a church’s architecture can burst or seem to want to burst their frames. This is not mere beauty it is the dynamism of passion – the truth of love and death.

Of The Last Judgement nothing new can be said, except it is a scene where judgement defies both love and death in an eternity of either suffering or eternal questioning of whether this can truly be love that so turns on dividing up human experience into terrible binaries. In truth no iconographic reading could ever rescue the painting from being one of the terror of judgement, where to be judged good feels as marginalising as being judged bad.

It is a great film – just sit back though sometimes and let your experience of the art overcome the art commentary going on and think for yourself passionately.

Bye till I come back – possibly with the piece on Heather Christle.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_______________________________