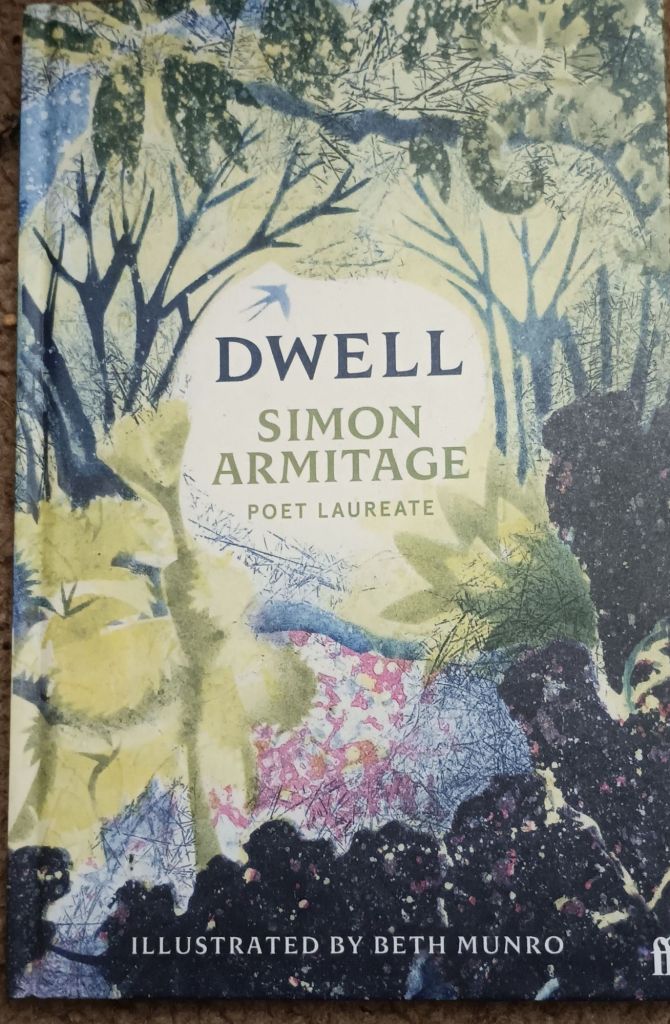

Why does Simon Armitage dwell on dwelling? A blog on Simon Armitage (2025) [with illustrations by Beth Munro} Dwell London, Faber & Faber.

The new poems by Simon Armitage that were published yesterday are inextricably linked to the Lost Gardens of Heligan, ‘Europe’s largest garden restoration project’, in Cornwall. They will also be ‘manifested physically within the Gardens at site-specifc locations and in different guises as installations, noticeboards, treasure trails, recorded readings, sculptures, etc.’. These quotations are from tne poet’s introduction to his new volume, wherein the poems appear merely ‘as text, as black shapes against a white background, trying to work their magic and cast their spells’.

But why Dwell as a title. At the end of his introduction, Armitage suggests the title is a kind of exhortation to the reader to a certain attitude of mind – a way of thinking, feeling and acting – describable by ‘an encouragement to slow down and spend time with ideas. “Don’t dwell on it,” people say, but I’m saying, “Please do.”‘ And herein is one meaning of the word which suggests that we linger longer or, perhaps, even ‘obsess’ on ideas and feelings attached to those ideas. That is, however, the second meaning of the word ‘dwell’ that he cites. The first is that meaning referring to the need of all animals, including humans, of ‘the shelter of somewhere to live’. Hence, many of the poems are named after the dwelling places of specific animals, dwelling places that reflect the essence of each animal.

However, it is possible that Armitage knew that for one poet, poetry itself was a thing in which h to dwell, though she saw it, as the opposite of a state of mind called ‘prose’, cramped by the demands of the real world functions of ordinary language from other realms of ‘Possibility ‘. To Emily Dickinson, poetry was synonymous with ‘Possibility ‘.

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –

Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my narrow Hand

This poem mimes its own meaning. The ‘narrow Hand’ is a synonym for manuscript writing, which, when that ‘Hand’ writes poetry, uses every engine of the writing for its ‘spreading wide’ in possible meanings. If a poem offers more windows and doors for communication with the outside world, it also spreads its ambition to the ‘everlasting’ in the natural world of forests and sky. And to such a house come worthy guests and visitors to ‘occupy’ it.

In mentioning that last idea, another theme in Armitage’s ‘Introduction’ comes to mind – his memory of his grandparents’ refusal to allow house-martins to ‘dwell’ with them. By making their ‘mud dome clinging to the underside of an overhanging roof’ an extension to a shared home with these elder Armitages, the house martins lay a claim to the right of sharing a world to live with humans. We need to share our dwelling Armitage thinks.

When Armitage tells the story of his grandparents there is an echo inside of me of a generational similarity of ambivalence about where we come from – though Armitage still lives there and loves it, I come from nearly the same cultural stock (a Yorkshire working class one cultured in the cusp of the Pennine moors, though I was first generation with university education, he was the second). The potentially shared ambivalence I feel in his funny story about Yorkshire pride with its monitoring of one’s neighbours doorsteps, washing lines or curtains for signs of dirt or laxity in hygiene or general lack of Yorkshire grit about one’s appearance to others. here is almost the ghost of am awareness of the cultural insularity of that culture. There is almost in the story the ghost of a critique of an older generational dislike of comers-in, that might amount to a dislike of migrants from elsewhere. His grandparents discouraged house- martins because of the dirt shed from their nests on the flags surrounding their property. I hear my dad here.

However, Armitage imagines how the house-martin migrants might feel, who having travelled from Africa with great risk are rejected from a dwelling they need to make in order simply to survive. There follows statements that might apply to deep structural dislike of migrancy and migrants, the necessity of sharing our homes (our homeland) and the effects of not doing which Armitage allows to become the making of ecological extinctions (‘House-martins are now a red-listed bird‘) of species. As I read this argument which amounts even to the accusation that house-proud failures of hospitality (ignorant of empathy) leads to ‘genocide’ (a word he chooses with caution but definitively has havinf ‘a certain kind of justification’) that in 2025 cannot but recall the depth psychology that leads to the genocide of Gazans (where the issue is not migration but territorial competition by settler populations) and to the current moral panic in the UK about HUMAN migrants and refuge-seekers.

Nevertheless the book remains one about species extinction and the need to ‘dwell’ on the need of each species to find a home appropriate to its culture and not one imposed by a dominant human animal species. For me though the analogy remains. To dwell on the tragic consequences of being unable to imagine otherness in order to preserve human dominance over the ecology of a region is so near to the ideological constructions of nationhood and regional ‘pride’ that the same psychological conclusions can be reached. If we dwell on the need of others for dwelling suitable tho them we support diversities that our insular ideologies do not. The tragedy is not only one for migrants (in this argument migrant species) and disregarded but unseen home species but also for the dominant ‘home’ psychology which limits itself by ‘disregard for life’ in others to a world where our capacity for wonder, curiosity, invention and empathy ‘ is ‘limited to our own perceptions and experiences, a kind of narcissistic echo-chamber, one-dimensional in all its dealings’.

There is an increasing tendency in Armitage to occult any radical statement about human political values, that may accompany being Laureate, and sometimes I feel a kind of Tony Harrison impatience with his occultation of radicalism about human politics under green issues in the surface of the poetic argument and not speaking out clearly as that earlier poet, a hero of Armitage’s, did. But the green issues are linked – perhaps fundamentally so and perhaps prior to the human ones that fuel racism, defensive nationalism and hatred of the other for challenging (without even trying to do so) one’s dominance culturally, psychologically and politically. And thus Armitage remains my hero – though he speaks out not quite so clearly in some respects, or too much in hinour of the established culture – even of monarchy.

But let me return to Emily Dickinson. The dwelling of poets is poetry because poetry opens up psychological potential or ‘Possibility’. I am certain that Armitage feels this about poetry though its likely source for him is that other radical who become Poet Laureate and occulted his love of humanity by dwelling in poetry alone, William Wordsworth – here locating it as a music of humanity transcending the local dwelling and finding it generalised in nature:

....., but hearing oftentimes

The still sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue.—And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

For the whole poem see: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45527/lines-composed-a-few-miles-above-tintern-abbey-on-revisiting-the-banks-of-the-wye-during-a-tour-july-13-1798

Armitage’;s music is more jazzy, more specific and it dwell in particular formerly un-imagined dwelling – in poems named after specific dwellings: Drey, Lodge, Web, Den, Hive, Roost, Sett, and so on. Some dwellings are ecologically complex and live in his poems in their interdependence, as in that lovely poem Pond, so complex that both the poem and the beautiful Beth Munro illustration see in double-reflected in a film on the pond’s surface – above and below (a beautiful conceit like that in seventeenth century Metaphysical poetry). But a modern version for the film also ‘stars (that is, it is a movie) ‘newts / and swallows’.This is a lovely volume. It can stay a merely ‘charming’ one read superficially (and it will be – such is the fate Poet laureates must embrace) but dive deep and dwell on and in these homes wittily described as emblems of the life-times of a species and you’ll find something ‘far more deeply inter-fused’, or at least I think so. Sometimes the cycles of life are not so much inter-fused as buried in excrement (like that dropped by house-martins, especially that of an owl who might just as well be an angel in the poem Nest Box.

A favoured poem of mine is Cote, about an incel dove ‘on my own in a honeymoon suite’, with their pleas to not ‘make me rhyme with love’.

That’s all today

With love

Steven xxxxxxx