‘But there is no sign of the boy.’ The coming to age of a queer boy told in the third person captures the alienation possible in that experience but that may be all it seeks to show! This is a blog on Michael Amherst (2025) The Boyhood of Cain London, Faber & Faber.

I sighed when I finished Michael Amherst’s debut novel of a queer boy’s coming of age. I searched and searched the final paragraphs of the novel for some hint of why a writer should think that this conclusion might bring readers to at least some plateau whereon the key themes of the novel would stand out visibly as guides to the many alternative lives that the boy at the centre of this novel might go on to live. Strangely, Michael Donkor in The Guardian seems to think that conclusion is fitting because the novel, which he earlier calls a Bildungsroman, is satisfying because it is not about this particular boy’s growth to some final or temporary life’s fulfilment as a kind of ‘Daniel come to judgement’ but a realisation that becoming an adult will never fulfill him, without as Werther in The Sorrows of Yong Werther does in that classic bildungsroman by ending his embodied life there and then. Here is what he says:

While Amherst offers us a perceptive and closely detailed examination of a unique child’s consciousness, the novel is really concerned with what Daniel comes to discover is at the heart of adulthood. Adulthood seems to him a “resolute and uncaring” state. And Daniel, with his judgmental mien and superiority complexes, his self-loathing and worries about his insufficient masculinity, his sense that his family’s frailties are for him to mend, cares profoundly – and suffers the lack of reciprocity painfully. In the middle of the novel, he beseeches, “Won’t anyone look after me?”

In the eponymous biblical story, Cain is marked or cursed for his crimes against God, and against his brother. As this exquisitely written novel reaches its brave and elliptical final sequence, we’re left wondering if Daniel is cursed to bear, for life, his unique sensitivity in an unfeeling world. Or if, adapting to the norms of adulthood, he will become just as unfeeling himself.

Michael Donkor (2025) in The Guardian. See: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/feb/15/the-boyhood-of-cain-by-michael-amherst-review-a-terrific-queer-coming-of-age-debut

This seems to be a description that oversimplifies the Daniel of the novel. Even the Biblical and literary types that characterise him are reduced in number to one, Cain! Moreover, the implications of even that figure’s typology is reduced in quality and even his main character association not followed through – for Cain is the murderer of his brother and there is a lot of tbat trait in Daniel. Of course, he never goes as far as murder, but he is able to disregard his duty to help others, especially boys who displeasure him, to go on living.

But to his mentor, Mr Miller, he is Peter Pan and Puck, fairy creatures that fascinate this far from ethical teacher. They fascinate but do not excite Miller because these boys have not achieved that state of near manhood that gives them S.A. to him [his name for Sex Appeal when raised, hidden in plain sight, in more open discourse wirhin his classes of young boys].

The net effect of all that self-conscious referencing is a complex configuration of sometimes contradictory qualities in Daniel, the Biblical type of the just judge, veering between innocence to the point of naivety and experience to the point of being uncaring, femininity set against masculinity as influencers on boyish development, and, sensed entitlement and social inclusion set against exclusion and marginalisation. What we definitely do not see is just ‘unique sensitivity in an unfeeling world’.

One of the means Amherst uses to distance us from the error of identifying easily and uncritically with Daniel is third-person narration that cuts across first-person perspective on the events of the story wherein Daniel himself sometimes comes to be referred to as ‘the boy’. Now, replete with disappointment about the limp end, or so it seemed, of this novel, from these last paragraphs, I intend to find clues as to why I feel as I do and check that feeling against the cognitive prompts from the text.

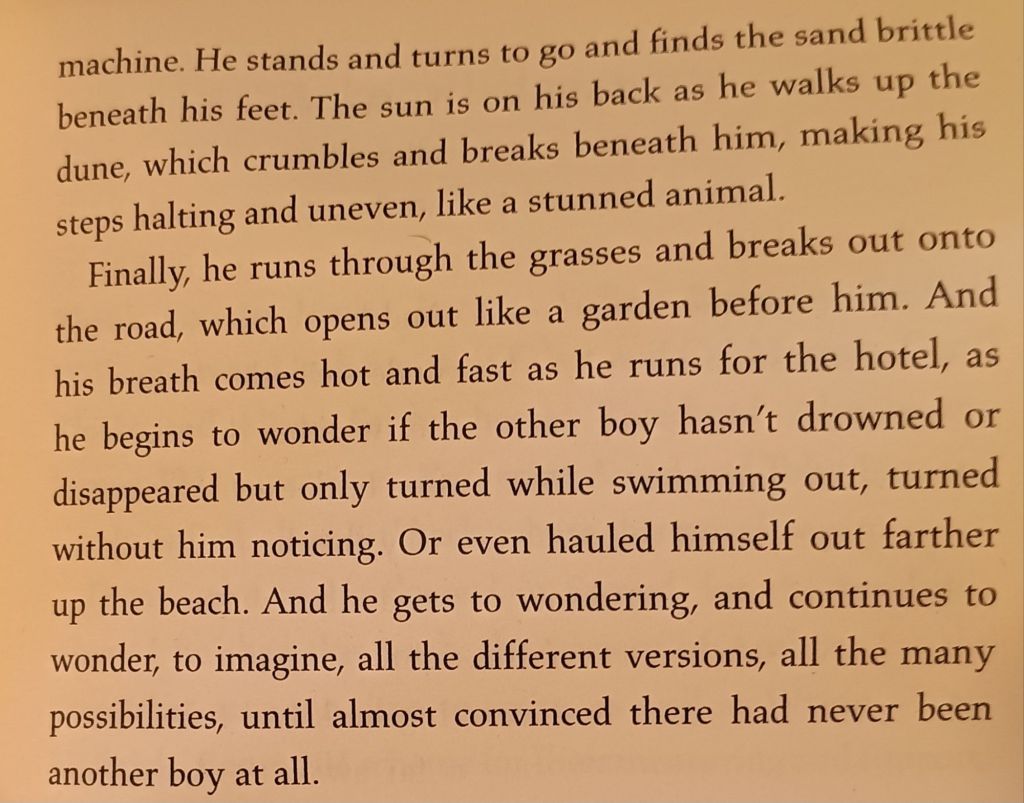

I will check them both in their content and their mode of proposing that content, the thing people wrongly call the technique and style of the writing as if separable from its content. Before the ending paragraphs, Daniel has noticed a ‘boy’ who serves him and his family at a seaside cafe. He follows the boy because he senses that this boy ‘has something that he wants‘. Watching him leads to observing the boy meeting a girl, which then leads to also becoming the observer of the couple having sex on the beach. Daniel looks on from a vantage point where he is the unobserved voyeur of the sexual happenings. After the sex is over, the girl walks off to the town, but the boy swims out into the sea, getting further and further from the shore and Daniel’s ability to observe him. The text below follows:

Michael Amherst (2025: 188f.) The Boyhood of Cain London, Faber & Faber.

The prose startles because of its insistence on the impersonality of the object of Daniel’s fascinated view – ‘the boy’ – yet this is the very way he himself is signified in the earlier narrative, rather than as Daniel. It is as if the text wanted to abstract the concept of the boy in order to query its contents. Hence the peculiar metaphysical feel of the search in these two paragraphs not just for ‘a boy’ but the ‘sign of a boy’, that which signifies the young male, still kept within the bounds of adult authority (which he thinks ought to be consistent). Daniel’s almost forensic judgement of the boy in fact shows the markers by which Daniel knows ‘a boy’ must be a being judged by authoritative adult standards of behaviour not yet attained – as someone who does not ‘go out too far’ or break limits such as the performance of sex, and in a way that is like an animal eating its prey or another animal, ‘consuming’ a girl as if she were ‘a distance of miles of open country’ with its sweated riding capacity. Boys ought to have ‘obeyed the rules, the rules that should apply to everyone’. A boy that is thus transgressive againstbrule and boundaries is a boy who is also travelling too far into the country of earthy manhood – the realm of that ‘made from sweat and leather and blood’.

As these two paragraphs end, and end the novel, ‘the boy’ who is now referred to ‘another boy’ is thought to be potentially a non-existent being, leaving then only Daniel to fulfill the role of ‘the boy’. It is as if that mirage he saw with a woman on a beach has fulfilled his obligation to a later life he resists and can only conceive of as heterosexual, even if only for a moment he knows that it the boy that he follows who ‘has something that he wants‘. As a queer boy (or gay or trans girl), he will never find a realisation, maybe even not a self-image to model that role, for who would choose to be the adult queer male Mr Miller, locked in secret places where his desire plays games.

The model for the hero is in fact, the model of young masculinity continuing into adult masculinity often invoked by Beryl Bainbridge. It is J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan for whom every life transition is alike and an ‘awfully big adventure’, Peter Pan is the name Mr Miller uses to refer to Daniel and it seems to be the reason that Miller never finds Daniel sexually and romantically appealing as he does Philip. Sometimes, Daniel blames his mother for keeping him as a perpetual boy:

If his mother didn’t love him so much then maybe he’d be normal. She loves him too much, with her constant fussing at the school gates with concern as to whether he has packed everything. He love leaves him feeling guilty. because he knows he is not worthy of it. It lays a claim on him, but it’s never as great as the claim he lays on her. [1]

Daniel’s ‘abnormality’ is increasingly sensed as represented by his body, which refuses to grow, as a whole and in selected masculine parts, as it should, and which mark boys from men. Even at the very beginning when he observes his father teaching the only boys he will teach (13+ years of age), as headmaster, he notices they differ from him and his cohort because ‘they have the long limbs of men. Some even have men’s voices.’ [2] At times, he lingers at the portal of wishing to be a woman, as he observes his sister and her friend doing their make-up and dressing for an adult female role. He must be a sly participant of these rituals, for though his sister finds his male presence a nuisance, like his suggestion of female clothing games in which he can take part, ‘he’d rather be a nuisance than barred altogether’.[3]

Yet he burns inwardly when the school photographer puts him with lower years of male development in his school because of his height relative to his own year cohort. He watches the other boys’ bodies as they change for swimming lessons, noticing in one ‘a puff of hair above the waistband of his trunks’. He does not wish for such a show himself: ‘he does not want his own, clean body sullied with hair’. [4] If bodily sex/gender maturity is seen as dirty by Daniel, we see other internal motives for his Peter Pan syndrome.

Meanwhile, the other boys like the comparison to their favour their bodies show to Daniel’s ‘childish” one. In the Games Changing room at this point in the story Daniel is alone with Philip, the boy he likes inexplicably, and whom, even more inexplicably, Mr Miller seems now to prefer to him as a student of art. It is at this point that comparative penis size – and the meanings that comparison bears – begin to matter to Daniel. The passage below is telling:

This passage is not only about comparison of growth spurts but their sexualisation, although there is a sense in which Daniel’s own supposed sexual innocence, compared to Philip’s ‘awareness … of doing something forbidden’, is entirely fake (or at least performative, as if innocence were as performative a state as that of experience – an idea Blake’s poetry sometimes seems to suggest).

Philip, though confused at first, not only posits in his own mind and Daniel’s not only the meaning of the display of his sexual parts to Daniel as a sign of not being ‘wanting’ as a man, but even posits through his ‘terrible knowing smile’ (and how could an innocent in truth ever be able to interpret that smile as knowing if they had not too eaten of the tree of knowledge) an offer that Daniel might find this sexually stimulating. I do not import here, by the way, the reference to the Tree of Knowledge, as a way of yet again citing my love of Milton: it is the name of the boy’s encyclopedia in which Daniel first greedily and fearfully views scenes of male circumcision rites in Africa where ‘what he wants to see, but the photo does not show, is the fact of the knife cutting through flesh’.[5]

The queer boy never does emerge in this supposed bildungsroman. Daniel clearly explores without any attempt to understand sex/gender roles, the various means of finding the objects of one’s sexual desire (pleasure and pain, their access through ranges of the senses for instance), and, of knowing which objects he can publicly admit to desiring himself (which is the analogue of Mr Miller’s attempt to imbue awareness to boys where it is they might express a ‘significant error of taste’).[6] At the moments where he might transition to an adulthood, one that all the adults he knows in the novel consider to be a ‘fixed’ states of commitment, he falls apart. Daniel is ‘disgusted’ by a ‘porn mag’:

by the nakedness, by the bodily fluids, the way the images are staged. There is nothing artful, beautiful or romantic about them. There is nothing in this ritual to appeal to him. It is animal. [7]

But the novel really never goes through the many doorways it shows us – those that the law, or custom make open or openable to us or the ones locked or forbidden, like the school doors to the upper school Danny thinks of as strange for they open only to him because of the privilege afforded by his father as schoolmaster but never when school is in process, only at weekends. [8]

When Danny sees Mr Miller slip a letter to Philip in the art class – clearly an invitation to some romantic or sexual liaison – Danny demands to know what it is, only for Philip to dismiss him as an immature sexual follower not up to men’s sexual congress, with women or together: “stop clinging to me like some little girl”. Knocked back into himself by these words, Daniel analyses what is going on between school master and pupil as about doors again – forbidden or otherwise, which might be asked to open to our desire:

The master has named his want of something and now he fears Philip sees it as well. He feels Philip drawing a line between them, as though his friend has entered a room, only to stand in the doorway and tell him not to follow. And if Philip can see it – if it is plain to him – perhaps it is legible to everyone else too. [9]

But of course we know now the novel ends with ‘no sign of a boy’, and not perhaps because he has become identified under the sign of a man, but in other forbidden but real codes that signify queer being.

___________________________________________

[1] Michael Amherst (2025: 143) The Boyhood of Cain London, Faber & Faber.

[2] ibid: 6

[3] ibid 142f.

[4] ibid: 171

[5] ibid: 89

[6] ibid: 119

[7] ibid: 91

[8] ibid: 5

[9] ibid: 159f.