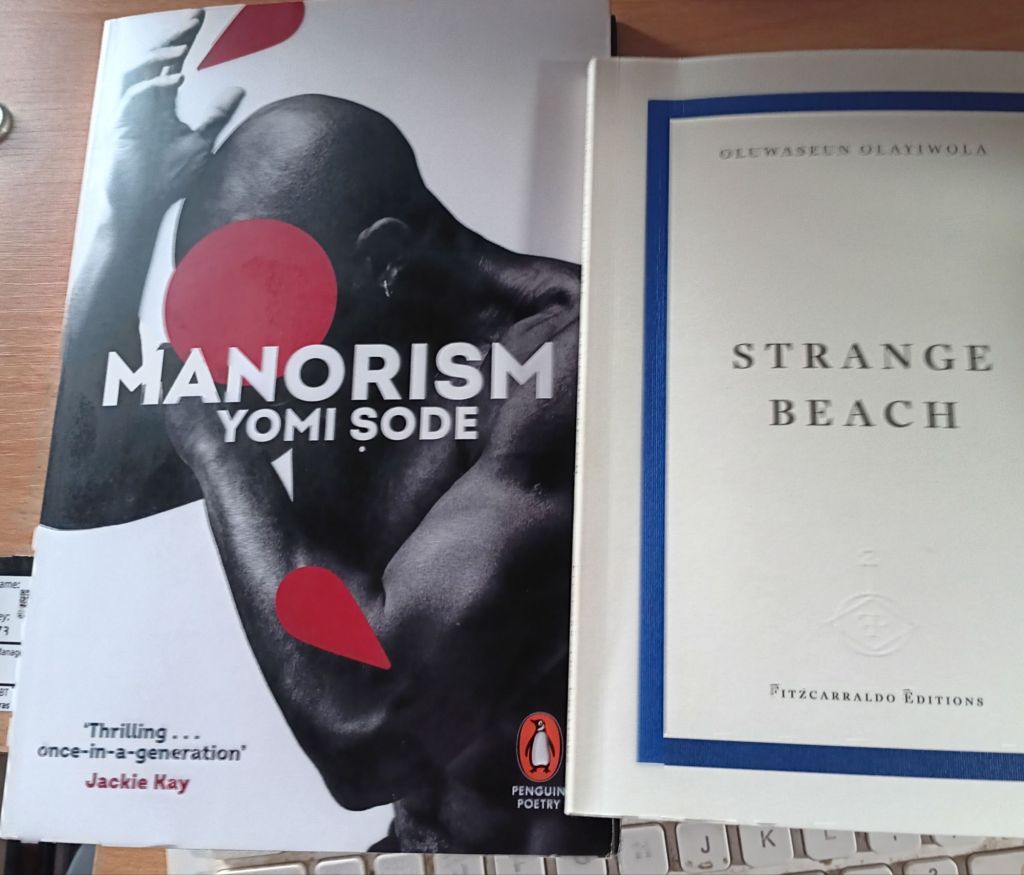

In an earlier blog post (see it at this link if you wish) about Oluwaseun Olayiwola’s Strange Beach, I ended it with a promise, or is it a threat, that: ‘I want to return to them. Maybe I will, for I have more to say of the brilliant things in Andrew McMillan’s book blurb on them on the book’s back cover’. Let’s start with the blurb:

In this exciting debut, the tideline of the poetic phrase is constantly thinking, is constantly shifting, is forever rebuilt and remade on the shifting sands of language, every grain of a word held up to the light to consider its myriad reflections.

Of course I read that before I wrote my blog and it fed in to the main generalisations therein about the nature of contemporary poetry and its relations to the traditions that have defined there idea of the poetic line to us. Before quoting myself though, I ought to insist that I do not associate contemporary poetry’s difference from tradition as an experiment with poetic line, just as Picasso experimented with the drawn line in graphic art. Such experimentation has long been acceptable in the transition – perhaps the best experimenter being Tom Leonard, that widely unrecognised Scottish poet of the greatest of power as a poet.

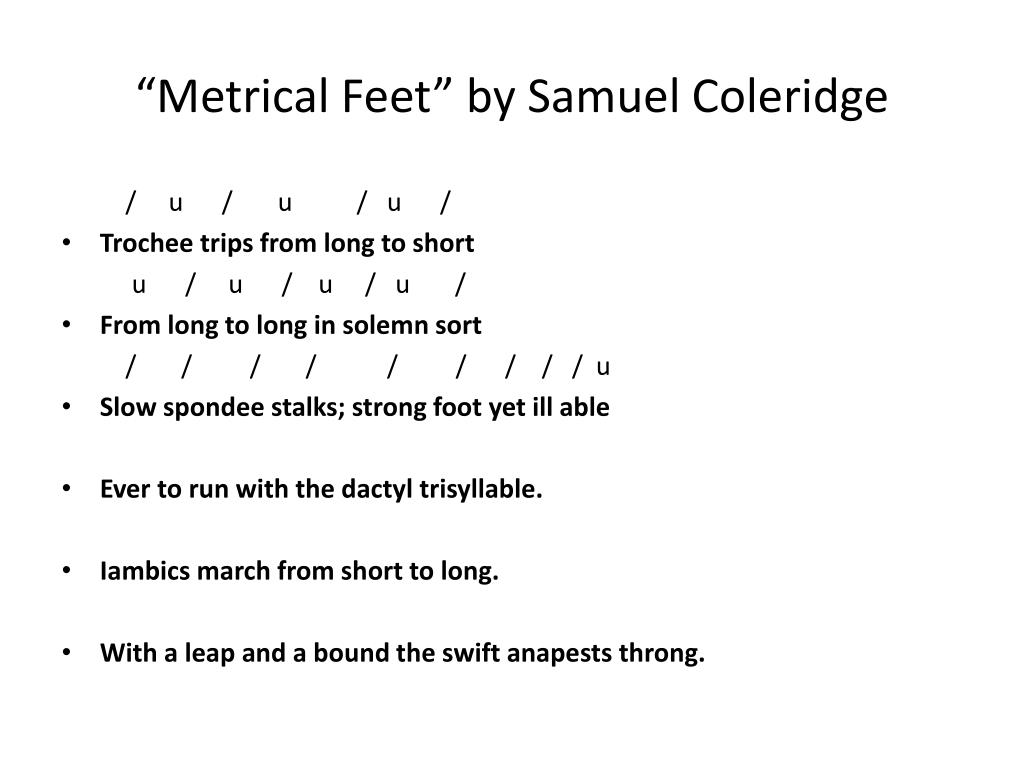

What I mean, I think, is that contemporary poetry is deep-mining the space of a written page to see how and why it was thought appropriate to fashion the architecture of poems on the visible and sometimes (but not always) audible concept of lines to the eye which to the voice has a rhythmic quality that in part was theorised by an underlying set of measurements of its sounds effects – an area of knowledge in the appreciation and critique of verse that we call metrics. Metrics was a means of discussing the sound qualities of poetry by virtue of a few prototypes of the pre-regulation of the music of any line containing a given number of syllables.

The metre of a poem (it is spelled meter in the USA) is describable by these prototypes – the most common being the iambic pentameter. A line was divided unto feet (the length of the feet in terms of the number of its syllables which depended on the metrical foot basic to the line), which could be tri-syllabic or disyllabic (3 or 2 syllables each respectively) mainly. The ‘iamb’ foot is disyllabic (a weak followed by a strong syllable), like the ‘trochee’ (a strong followed by a weak syllable). Some people believed that metrics was only feasible in a language considered as based on the length of syllable sounds – a language like ancient Latin , it was argued – though others said modern languages replaced the idea of syllable length with syllable weight or stress in describing the difference between a stronger and a weaker syllable sound comparatively within a foot. The metre of a line was then characterised by the number of feet it contained – a pentameter obviously having five feet. For yet others metre was a construct that bore no reality – verse had rhythm, these people argued of which metrical pre-arrangement, with its permitted flexibilities,was either just a partial contributor to rhythmic creation in words OR, in a great poem, entirely a myth. In a great poem, the latter argued, rhythm could be described in many ways and use divergent theories, like those proposed by Gerard Manley Hopkins for his own verse or those based on earlier poetry with irregular line lengths, as in Ancient Norther language poetry include Old English. For examples I point you elsewhere: though the account confines itself to the description of iambic and trochaic feet (use this link).

In my first blog (on Oluwaseun Olayiwola’s Strange Beach – use link to read it) I spoke thus of the kind of poetry I interpret as ‘modern poetry’:

It seems to be characteristic of modern poetry to refuse to support the music of voiced poetry as it tries to interpret line formations together with distributions of them in space that cannot strictly be ‘read’ and yet must be. The modern line is not strictly, or even flexibly, metric, though it sometimes invites traditional readers still to count syllables as a test of the fact that most of the effects of metrics can be realised without its quantitative machinery.

Thus does it matter that’:

‘the sing / ing com / peti/ tion, he / reckoned’works as a near iambic pentameter with a final trochee. Probably not. The poetry works in fact by requiring the reader to voice the lines of poetry – even if silently and to the inner (and progressively inward-going) ear, whilst demanding that the reader account in their voiced version of that reading to themself or others for the appearance, or ‘look’, of its text on the page – the distribution of its lines amongst blank space and between blank spaces. Often, these spaces are internal to the line. The master of this practice is Andrew McMillan , who occasionally acts as if the within-line space is a version of the caesura in Latinate poetry, but not ever consistently thus. These features are, in fact, part of the shift in poetry from quantitative to qualitative measures of its value and beauty that require the reader’s co-operation in completing them and their effects .

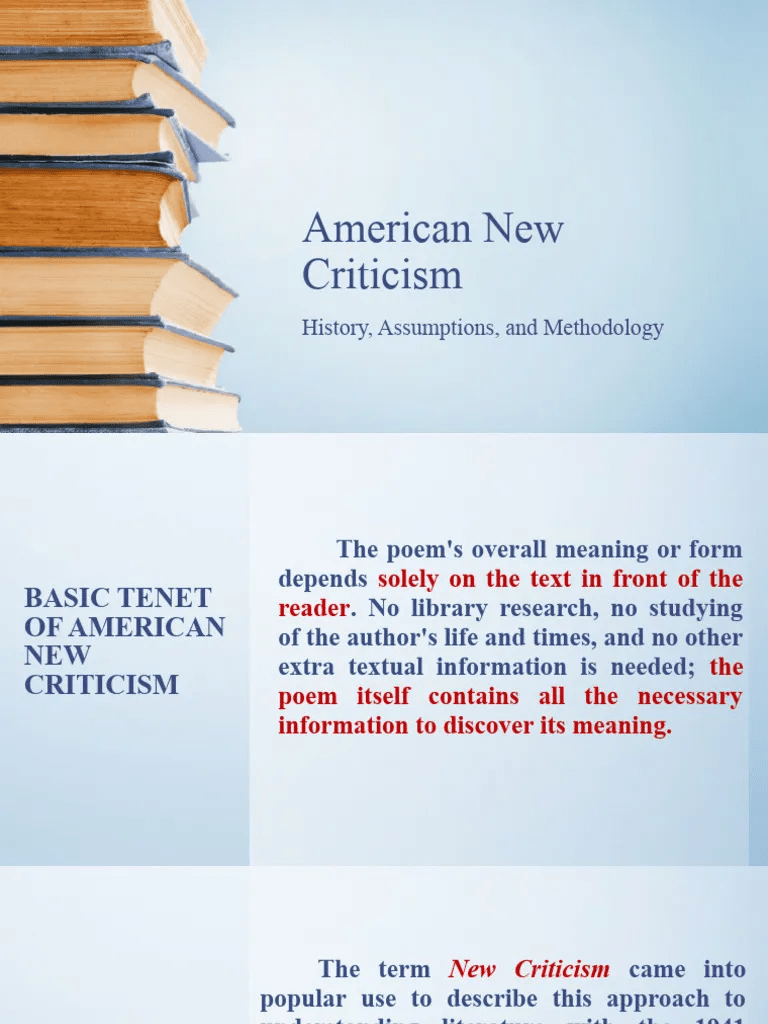

It could be that I am here only invoking the rather brutal debate in American literary criticism that, on one side, insisted that metrics quality was an entirely independent feature of poetry and the sane side of the argument that insisted that the meaning of words in the poetry influenced and interacted with their metrical qualities. An example of the former is John Crowe Ransom, who as a poet and academic ‘New Critic’ insisted that the ‘proper province’ of literary criticism included ‘technical studies of poetry, metrics, tropes, and fictiveness’ (I take the description from this linked site) and likewise these features had their ‘own charter of rights’ and should ‘function independently’ of the meaning or intention of a poem. Terry Comito ( I cite him from a very pertinent blog at this link) distinguished the poet Yvor Winters (and hero of the young Thom Gunn) from the New Critics and Ransom in particular, even though he was sometimes wrongly linked with them:

Winters insisted again and again that literary language is … a refinement and perfection of the language in which society conducts, or seeks to conduct, or fails to conduct, its everyday life. The poet’s language is not, therefore, exempt from the responsibilities incurred in our worldly projects. Indeed, for Winters, it is particularly accountable, and he spent much of his career calling poets and critics to account with a ferocity that seemed unbalanced or faintly ludicrous to those for whom literature remained an academic pursuit.

In brief, Winters felt that poetry is a form of communication like any other human communication and did not evade consideration of the meanings through which it used specialist language types like metrical verse lines. Indeed, one wonders if without consideration of meanings any verse line can be read at all – even as a sound pattern, not least because of the shifting pronunciation of words over different sociocultural, time and space co-ordinates. For more on this read the article linked to here [from 1954] by Victor M. Hamm.

What McMillan calls the ‘poetic phrase’ in his blurb commentary on the book cover of Oliwayiwola’s Strange Beach is negotiable in thinking of how the various poems in the volume work. Some of the poems play with their distance from conventional poetic forms with their regularities of form and interior development set in tradition, however flexible that tradition. The best example is that poem named Fumbled Sonnet , which is no way a sonnet. Yet what it is as a poem, though beautiful and visceral at one and the same time, I cannot yet say. There are three poems named Strange Beach in the volume. If we look at the first of these – the first too of the volume – we might attempt to discover what McMillan saw generally in the poems. The first Strange Beach is followed by lines cited from Claudia Rankine that offer a kind of gloss on its terms, not least the central one of the ‘strange beach’ :

.......; each body is a strange beach, and if you let in the excess emotions you will recall that Atlantic Ocean breaking on our beads.

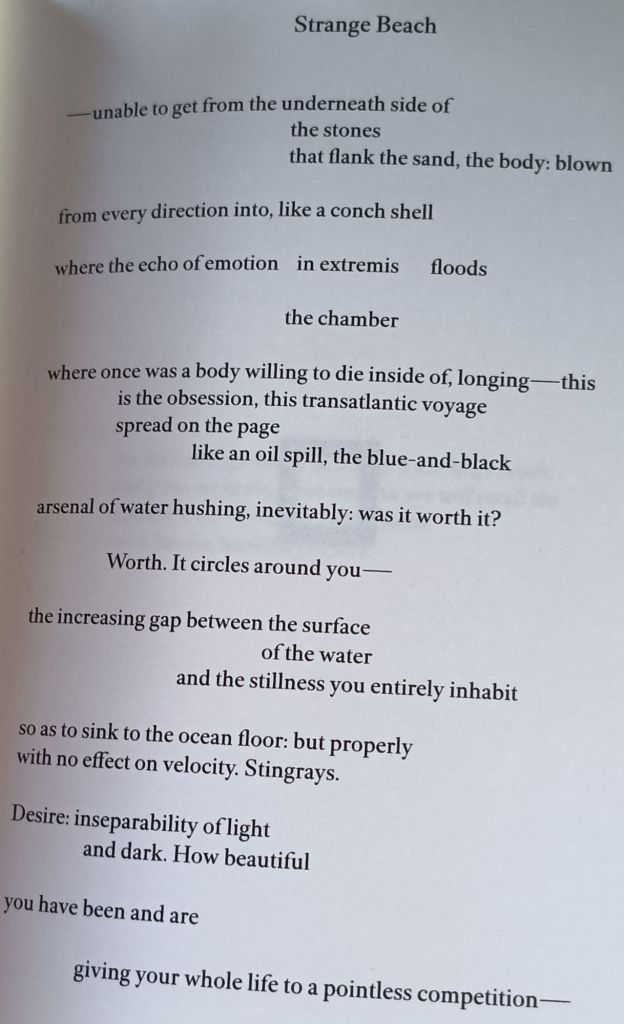

Here is the poem:

Strange Beach, p. 13 of Strange Beach

What was it McMillan said? It was that ‘the poetic phrase is constantly thinking, is constantly shifting, is forever rebuilt and remade on the shifting sands of language, …’. How would we know that a phrase is ‘constantly ‘ thinking and, in order to do so, is itself ‘rebuilt’ and ‘remade’. In order to look to this end, we would expect the phrase to enact modes of thinking by allowing itself to shift the context of its typology as a phrase – its relation to the generation of meaning in qualifying a main statement in strange and queer ways. For instance, it takes time to realise as we read this poem, that ‘the body’ is the main grammatical subject of the first sentence, partly because the subordinate phrase that opens the poem is also presented as emergent in the midst of things [in media res]. The body is not seen or felt or heard before we read that some parts of the constituents of itself – the sand that altogether compiles it into the beach that becomes its metaphoric substitute in the poem.

The sand at the margin of the beach is trapped under the weight of stones that imprisons that marginal sand beneath themselves. It sets the context that if the body is a ‘strange beach’ in Rankine’s terms, part of its edges are trapped in and under some oppression. Yet otherwise, the sand on a beach blows where the wind alone wishes it to do, subject to other forces but never held down. These are the contexts in which a ‘beach’ might feel and think of its dimemma and condition. They widen to include other beach-related elements, a conch shell – things now not only with a margin with other things but an inside and an outside, and then the sea that defines its other margin which has both lateral extent and depth. All of these factors in proliferating subordinate phrases add to the complexities of describing a ‘body (with its senses, emotions, thoughts and desire for action inbound, as a ‘beach’. The body thus can become its own obsession to resist stating in one place and wishing to ‘die’ (with all the poetic richness of that word) in other bodies. A beach as a poem is also then a process of motion away from itself and one body to many and all can be expressed as the spillage of ink on an empty page (the poem- and in doing so becomes a poem. And as essential a poem about the queer body as more than a ‘strange beach’ but certainly one of those.

where the echo of emotion in extremis floods

the chamber

where once was a body willing to die inside of, longing - this

is the obsession, this transatlantic voyage

spread on the page

like an oil spill, the blue and black

arsenal of water hushing, inevitably : was it worth it?

Worth. ......

When poetic phrases think, they remake in potential every element that creates sense and meaning in them for a reader – the semantics and associations of lexis/words, the agency of syntax (the relation of subordinate and main clauses), spatial placing in the contest of both words, word phrases and gaps – intra- linear, inter-linear and shifting effects of marginal space around them – all illustrated in the cited lines above) and the effects of internal performative (even if internalised) voicing interacting with all this. This is why – an image seems to suggest a poem written on the surface of water, its ‘page’, but then to hint at the depths that make it mean beneath its surface:

the increasing gap between the surface

of the water

and the stillness you entirely inhabit

so as to sink to the ocean floor: ...

The ‘gaps’ are read here as if they again rethought thew nature of bodily emotion, but it does not make them easy reading – and all that is implied by McMillan’s formulation of phrases that are rebuilt and remade in the process of us attempting to read them, and thus gain insight into the nature of embodied emotion in a poem wherte metaphor, sound and linguistic / semantic structuring merge.

Yomi Sode’s Manorism is a set of poems entirely unlike those in Strange Beach, but I think we can use the dame issue of the reformulation of line within it, in part as a prompt to the voicing of the poems. Sode is a highly self-conscious poet and he raises the issue of what poetry is, and how it evaluated in one of the poems in the volume. In a poem called The Exhibition 2.0, he compares himself to the Black salvage-diver from Mauritius who led the team of salvage divers who successfully raised treasures from the wreckage of the Mary Rose for Tudor King, Henry VIII and to the African court-jester, Orazio Mochi. Francis was a Black worker whose world-renowned skills rendered him, in his own mind, the equal of those who in official documents belittled him and his value as a person. The same occurs to Sode who is told that:

my writing is not poetry? Though I craft each stanza hoping to be accepted. ... There is no room for the jester to say Enough, unlike Jacques, soon clocking that educated verbal performances are not what is desired of slaves, to speak requires thinking, to think means feeling, and to feel means Jacques, the jester - me - are of flesh and bone, like them. We are nothing like them.

Look above at the concern with poetic tradition and convention. It emerges in Sode’s insistence that he is BOTH equal to the demands of the tradition and to move beyond it in skill, though in writing not easy to recognises as ‘poetery’ by any conventional yardstick sometimes – in this poem verse paragraphs are used not ‘lines’ as such, that rewrite how poetic skill is recognised, or would be recognised if you were not Black and though culturally incapable of the achievement of the standards of White culture. .

And I cannot (not yet) offer readings of Manorism.It is a volume I need to live with and reread many times, to learn, for instance of its use of ironies and humour as well as the value it gives to confuting some of the boundaries between poetry and prose. A lot of this is not about the difference of verse poem and prose poem but about learning how space works and is read in text, and embodied by inner and outer voice by being mobilised as implicitly spoken not only read – but using the visual cues of reading to intuit the audible voice, including its pace, rhythmic quality, and tone. One poem (We Gon Be Alright) is a three page block of prose – or what seems so but which is about the resonance of the word ‘lie’ and ‘lying’, the invocation of poetic forms like chant and plainsong, and the idea of the authentic and inauthentic voice and their blended nuance.

This is a cop-out, I know. But these poems are so powerful and urgent. Manorism is a playful title. It relates to the term ‘man’ (as possibly an ‘ism’ like ‘racism’) in its themes of masculinity, the term ‘manor’ in its use as a term for black local community in London and even the near homophone ‘Mannerism’ because of the concern with Caravaggio and Graham-Dixon’s readings thereof. It is, I have to say – too much to get my head round know. But wow! What poetry!

Read both books.

All my love

Steven xxxxx