The poet is visiting Lighthouse Bookshop in Edinburgh on 11th March 7 p.m.

I have enjoyed very much reading the debut volume of poetry by a new queer Black poet, Oluwayseun Olayiwola, called Strange Beach. For this blog, perhaps the first of two, I will concentrate on one poem because it centres on a compliment given, and the stress waves it sets rippling out from the moments of its articulation. The compliment becomes the poem’s title, but a title that the poem demands also is its true first line, words referenced by its apparent first line.

This poem does not seem to me typical of the central domain of the volume, set on recurring visits to a beach in which a world of men are cruised, selected from, and experienced as they experience, differently, what things the poet offers. However, the poem is again about an interaction between men, hard to interpret by each participant in the interaction.

It seems to be characteristic of modern poetry to refuse to support the music of voiced poetry as it tries to interpret line formations together with distributions of them in space that can not strictly br ‘read’ and yet must be. The modern line is not strictly, or even flexibly, metric, though it sometimes invites traditional readers still to count syllables as a test of the fact that most of the effects of metrics can be realised without its quantitative machinery.

Thus does it matter that’:

‘the sing / ing com / peti/ tion, he / reckoned’

works as a near iambic pentameter with a final trochee. Probably not. The poetry works by requiring the reader to voice the lines of poetry – even if silently and to the inner (and progressively inward-going) ear, whilst demanding that the reader account in their voiced version of that reading to themself or others for the appearance, or ‘look’, of its text on the page – the distribution of its lines amongst blank space and between blank spaces. Often, these spaces are internal to the line. The master of this practice is Andrew McMillan , who occasionally acts as if the within-line space is a version of the caesura in Latinate poetry, but not ever consistently thus. These features are, in fact, part of the shift in poetry from quantitative to qualitative measures of its value and beauty that require the reader’s co-operation in completing them and their effects .

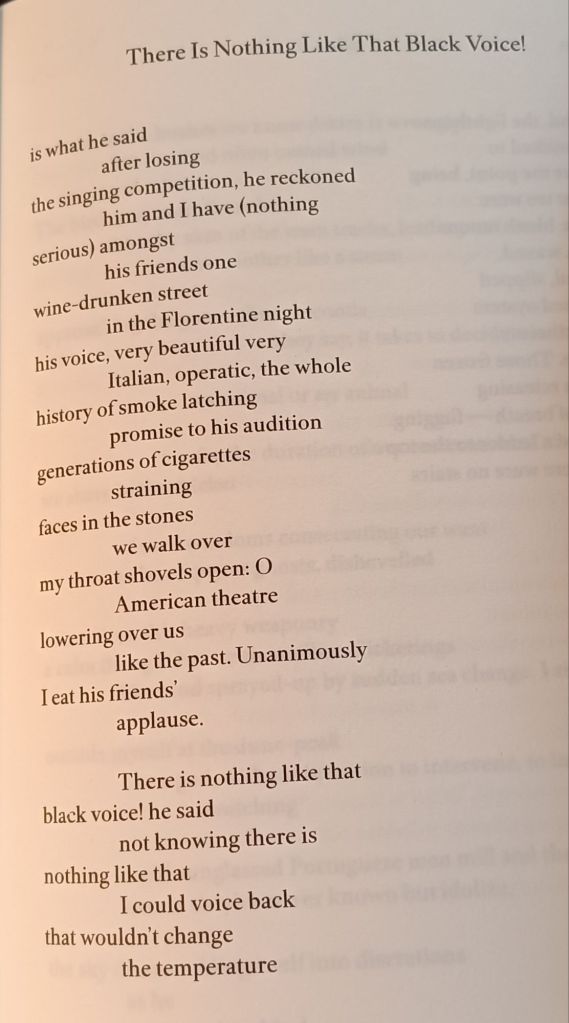

Nothing makes this clearer to me than Olayiwola’s ‘There is Nothing Like That Black Voice’. Here it is in full before we dive into its open spaces to grapple with its words, sung, spoken and enchanted and their multiple potentials.

Such poetry lives in meaning that shift even between repetitions of the same words in different spatial configurations, as a virtue of how the poet’s spacing works. Lets’s compare such a repetition and variation (in the manner of a musical variation on a theme, from this poem:

There Is Nothing Like That Black Voice!

is what he said

There is nothing like that

black voice! he said

not knowing there is

nothing like that

I could voice back

You cannot quite parse these lines without showing the limitation of that exercise. What matters is how even the basic sounds in the phrase ‘there is nothing like that’ are essentially words that change reference in BOTH their syntactical AND visually spatial contexts. Try, for instance, to say something about the meaning of the word ‘that’ in its various placements to eye and in different syntactical and semantic functions here, across these lines. There is inevitably resonance though between a ‘black voice’ and what the ‘I ‘ of the poem, a male with a Black Voice’ is allowed to ‘voice back’, or not as the case may be . Here ‘I’ is not being allowed to ‘voice back’, by some unwritten rule about not raising (OR LOWERING) the social temperature by contradiction of a primary speaker’s voice. Is that because the primary speaker does not have a ‘Black Voice’, but a white one. Nevertheless there is force here to force ‘that to have different meanings in each context and not only because the last very phrase of our chosen line end above (‘voice back’) is twice rhymed with ‘like that’.In one case of ‘like that’, ‘that’ distinguishes the ‘black voice’ as a distinct phenomenon though in the last example above ‘where ‘that’ refers to the nature of the statement itself ‘There is nothing like that black voice’ as something without comparison.

In an obvious sense the speaker refers to not being able to reflect the comment, and passing it off as a compliment, the form of words: ‘There is Nothing Like That Black Voice’. If he were to say ‘There is Nothing Like That White Voice’, it would shift the register of the comment to one that analyses its racist content and motivation, however unconscious that motive was in either speaker. In its originate voicing, after all, the statement says, does it not, that the essence of that black voice I discern as a voice only without listing what it says is like nothing else, and hence ‘like nothing’. The phrase negates, as it does in the sixteenth and seventeenth century sense used by Shakespeare (see my blog on that at this link) where it was used to define women as a hole or vacancy (nothing was the sexual slang for the vaginal ring – the absence of a thing (a penis). Likewise a white male lover talks of his black equivalent ‘voice’ as ‘like nothing’, similarly a vacancy or empty space – a blank to be filled by some thing belonging to a primary speaker. The lyricist’s voice indeed even provides this meaning in the poem:

my throat shovels open: O

Is that the character in writing O or a nought (0), a representation of nothing. In any case it is an open space bounded by some convention or other, and what it sings we know not, except that ‘there is nothing like that black voice’ – an articulated emptiness – perhaps the product of those inarticulates of the white :

American theatre

lowering over us

like the past. ...

Is this a statement of how applauding friends welcome and likewise compliment the ‘black voice’, as a thing of beauty but essentially empty of any THING that gives it meaning and reference. In contrat his white lover’s voice id full of a noted history – even if it be only that of the smoking that has grated his voice in sonourous quality or the smoke of white industrial history:

his voice, very beautiful very

Italian, operatic, the whole

history of smoke latching

promise to his audition

generation of cigarettes

His ‘whole’ is complete not the hole of O, stuffed with traditions – opera and smoky voices – that means his friends give him audition: they listen to him, not categorise him as the product of a racialised voice: There Is Nothing Like That Black Voice!. In truth in the narrative of this poem only the lover sins thus. There is no saying how authentic and meaningful is their applause, though the lyricist can ‘eat’ it – stuff his open mouth. The ‘loving’ friend is anyway quite competive. Twhat makes him accept his loss of the singing competition only his interpretation tells us occurred between him and the lyricist is because it was:

the singing competition, he recokoned

him and I have (nothing

serious) amongst

his friends one

wine-drunken street

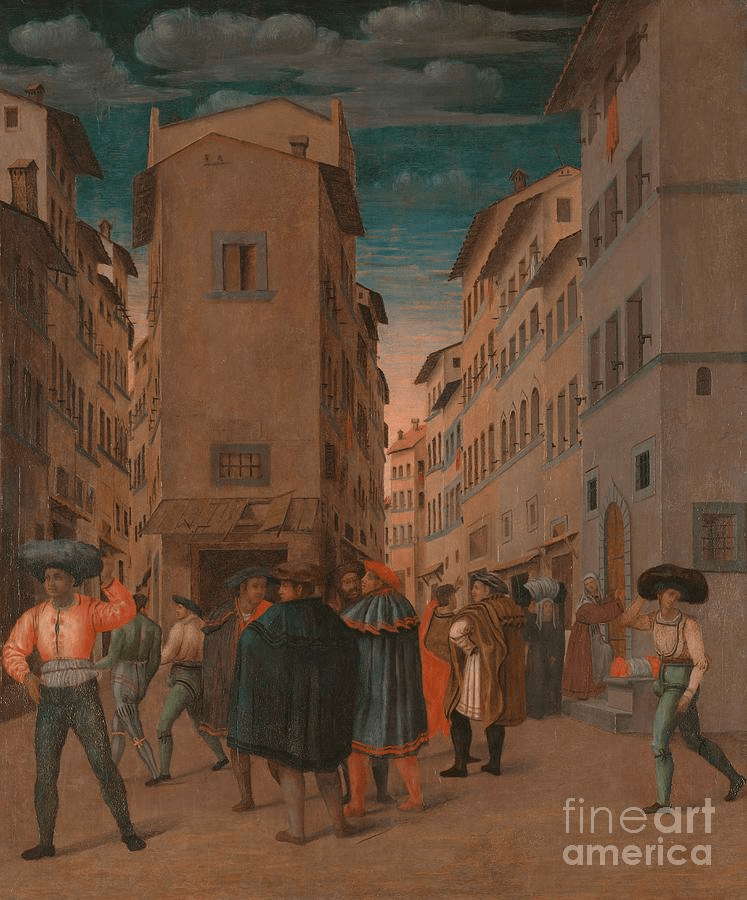

in the Florentine night

You won, he says, but it was ‘nothing serious’ that was going on! Had it been ….? And we reading also hear anyway that undercurrent in this song ‘him and I have nothing’ – little that differentiates he and his friends. Such rich reading play around how spacing trumps so often marks of punctuation, even open parentheses. And felicities that place the event in one ‘street’ rather than one night, also reduce the tempo.

This is by no means the greatest, or even one of such, in a poetry collection that soars, especially in the Strange Beach opening poems of its first three sections. I want to return to them. Maybe I will, for I have more to say of the brilliant things in McMillan’s book blurb on them on the book’s back cover.

With love

Steven

One thought on “‘I eat his friends’ / applause’: a poem on ‘a compliment’, perhaps: Oluwayseun Olayiwola’s ‘There is Nothing Like That Black Voice’”