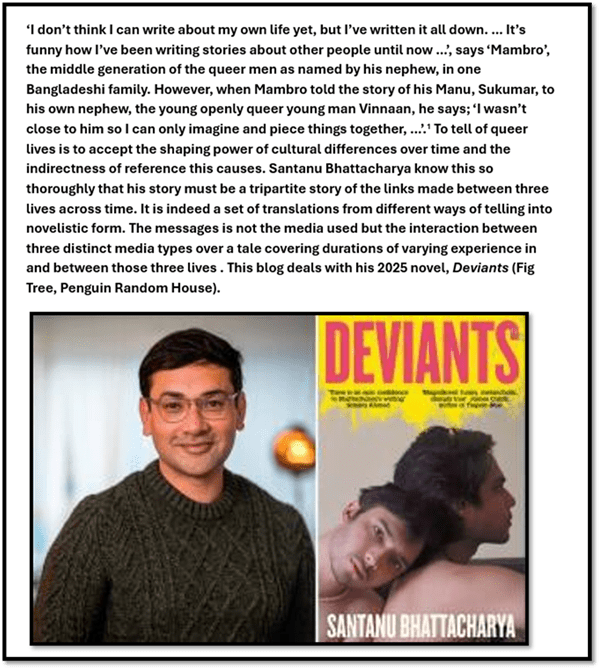

‘I don’t think I can write about my own life yet, but I’ve written it all down. … It’s funny how I’ve been writing stories about other people until now …’, says ‘Mambro’, the middle generation of the queer men as named by his nephew, in one Bangladeshi family. However, when Mambro told the story of his Mamu, Sukumar, to his own nephew, the young openly queer young man Vivaan, he says; ‘I wasn’t close to him so I can only imagine and piece things together, …’.[1]To tell of queer lives is to accept the shaping power of cultural differences over time and the indirectness of reference this causes. Santanu Bhattacharya know this so thoroughly that his story must be a tripartite story of the links made between three lives across time. It is indeed a set of translations from different ways of telling into novelistic form. The messages is not the media used but the interaction between three distinct media types over a tale covering durations of varying experience in and between those three lives . This blog deals with his 2025 novel, Deviants (Fig Tree, Penguin Random House).

Deviants tells the story of three queer men, each representing one generation in a Bangladeshi family and the interaction of either or both of all three of these men and their stories with each other. I want to stress the differentiation I intended in the last sentence between these three and their stories, for sometimes the interaction is only between stories and the way these stories get told. The men and their names indicating their co-familial-interrelationship (with the hint that familial names become slippery in time and usage) are:

- Grand-Mamu (the Great Maternal Uncle of Vivaan and hence the Mamu (mother’s brother) of Mambro and thus addressed by the latter), Sukumar (it means amongst other things ‘tender man’ in Hindi).

- Mambro (the brother of Mother), a name given to the middle generation queer male novelist (domiciled in the UK) by his nephew Vivaan, instead of the more formal name of a biologically related (or indeed some who are non-biologically related) maternal uncle, Mamu. Brother, by the way, is also a name which begins to lose its familial suggestion and take on the modern connotation of a familial relation by choice and community (one’s ‘bro’) when Mambro’s long-term partner enters into the story much later and is named ‘CoolBro’ by Vivaan.

- Vivaan, the cool Generation-Z teenager, savvy (as is intended by the classification label Gen-Z ) with the internet. Vivaan, however modern has a traditional name – honoured in Sanskrit and Hindu as the name of a bringer of new life:

- ‘Vivaan, a name of Sanskrit origin, means ‘full of life‘ or ‘rays of the sun‘ in Hindi. It symbolizes vibrancy, energy, and a zest for life, reflecting both India’s ancient heritage and its timeless charm. Vivaan connects cultural pride with spiritual growth’. The name’s modern appeal and phonetic charm have made it increasingly popular in India’.[2]

How do stories interact? Well first characters know and meet each other, although never all three at one time since Grand-Mamu is dead before that can be possible. Vivaan meets Mambro several times, just as Sukumar knows and meets his nephew young Mambro. Both uncles feel an especial relation to their nephews, symbolised in dance.[3] But stories interact in other ways – as oral tales (in Hindu, Sanskrit or Bangla) exchanged between pairs, each of uncle and nephew, and written documents – exchanged and transmitted and then translated into one novel in English. The participants read or read of each other. Mambro as a novelist transmutes, it is hinted, his experience into the characters of his novels – strictly though they are other people, although his own tale is told in his manuscript. Mambro represents a kind of first man, as implied by the Hindu reference embedded in the word manuscript (of course the word literally derives from the Latin manus meaning hand) . Manu is the name of the archetypal man and his successors in Hindu and Sanskrit text.

We hear of the three men’s interacting stories in different ways. Vivaan makes ‘voicenotes’ on his smartphone and digital apparatuses, and his contributions are those he presumably transcribes to form the printed text. Mambro is a writer (and re-writer – for revision of lost, damaged or damaging text is his forte) by hand in at least two manuscript texts, one is lost or thrown away in the sea coast. Some pages – the novel insists – remain ‘loose’ but get re-attached in the novelistic telling. Sukumar does not either write, or record in another way, his story, for most of it remains secreted – perhaps even to himself. He does give an oral version of his story to Mambro, and it is on this – a third-person narrative presumably as told by narrative Mambro (or retold by Vivaan – who may well succeed Mambro as novelist) – that our knowledge of Sukumar (or him as he is understood by his empathetic queer’ descendants’) is gained, but even then that knowledge is partial. Readers who know of our history as queer people know Sukumar dies of a complication of AIDS (the circumstantial evidence so fits the story told and retold of death by ignorance and in ignorance (all generated by a society unsympathetic to us) of that disease in our community of death by AIDS) – yet no-one can ever say for certain.

These related queer characters also get related by the names of their ‘first loves’, during their teens. In one meeting between Mambro and Vivaan, as told by Vivaan, the latter ‘asked him if he’d had a teenage love story, and he said yes he did, he’d tell me all about it’.[4] The characters of their mutual teenage stories relate exactly as that, as characters – as subsequent letters of the modern Western English alphabet. Being the last in line and a member of the Z-Gen, it is no surprise that Vivaan’s first love story as a double aspect reflecting the effect of American English on modern Indian cultural usage of English. Falling in love with Zee, in Amero-teen manner for Zee is the sound made by the name of the letter Z in American English, only to be replaced by the Anglophone lover of digital origin, Zed (the English sound of the name Z). But his queer successors in the novel have related pseudonyms given to them: X for Sukumar and Y for Mambro, so that the sequence of teenage love stories is precisely that of the Western Latinate alphabet’s end: X, Y, & Z. This is a clue I think, that though all those pseudonyms are justified by the culture of their times, beginning with the term that is totally variable in value in mathematical code, to one that resembles in sound the question ‘Why?’ (for Mambro could have taken more control in that relationship), to Zee being a ‘real’ nickname and Zed the online ‘double’ or avatar of the person named Zee..

No reader, me included, will find this novel to be obviously mechanical and functional in its structuring of the reader’s experience of the characters in it. However my rather functionalist references to the mechanisms in the novel do show, at least, that this is not a novel that wears its representational heart on its sleeve. It reads, of course, like the story of our real queer friends and chosen families, as if born from deep in queer community experience and the real-life values of some of its communities and their memories, even in the many queer spaces it evokes from out of real time and space – the cruising spaces of the Docklands in particular. It continually locates the building of practical relationships and the nature of different queer relationships, in domains of life that in their shifting interaction with each other our experience (as readers if we have not as persons) the whole continuum of experiences of different relationships from the anonymously visceral to the embodied form of near spiritual ranging from the romantic through mutual deep attachments to practical co-dependency.

We never forget that Mambro is a novelist used to fictionalising the real and realising the fictional as writing, nor that this is an aspiration he sets for Vivaan, whose writing does improve from exposure to the signed first editions of his uncle’s novels that he boasts to Zee he has in his room. This novel sometimes seems to bear the message, so frequently exchanged between people to ‘be yourself’: except it expresses it in terms of story-telling. As a story, rather than the recounting of a ‘dream’ (a dream to which we must return as we dive deeper into the novel), it opens with Vivaan relating the story so central to the novel – even though it itself will not be fully told in all its detail for a long time after in the text – that he calls it not a ‘chat’ in a coffee bar but THE CHAT, one about the ways that gay lives shape themselves (and which we will later learn follows Vivaan making plans for his own suicide – which is unfortunately how some lives have shaped themselves in and out of fiction formats).

Mabro and Vivaan dp not talk about Vivaan’s life thus far but indirectly as if speaking only of storytelling. Vivaan responds to Mambro asking him what ‘he would name his story’. They play the game, possibly as a means of accessing truths not otherwise tell-able, of constructing one’s story as the plot of a commodifiable story, a novel or short story perhaps that will sell. I am not sure I would buy a novel called ‘love at first tap’ but it is Vivaan’s story – a story of dual means of finding love on a keyboard (accessing the real Zee orr the virtual Zed) linked to the global internet and social media. The tone this sets the novel is by necessity abstruse and contradictory. Mambro wants Vivaan to write his story authentically, or so he says: “tell it yourself as it happens”. This phrase is anyway a kind of fictional sleight of hand of novelists, like the fictional Mambro, who forget that no story is told without some inevitable and necessary lapse of time between what happens and telling it – to say nothing of writing it by hand, typing it or (and here’s a duration for you) publishing it in some way or other (formally or informally). Moreover this call to writing authentically is shaded into chiaroscuro by motivations a long way from the desire to write authentically ‘one’s own story’. Indeed those shades include owning your own story as one’s own capital, so that if anyone makes profit from that capital it will be you. Defending his title as the game continues, Vivaan says:

… At least it’ll sell!

Well you should write it then, he said.

I was like, for real? Now I knew he wasn’t joking.

Yes, he said, you should tell your story yourself as it happens. Otherwise, you will have to reconstruct your own life from scraps of memory later. Or worse, someone will tell it on your behalf. They might even make loads of money from it! [5]

How else would a novelist look at stories but as things that, however authentic of real experience, appeal to a market for them, however undeveloped as yet – a market for instance for queer novels that would not have existed in the days of queer silence lived in by Sukumar, one that was in its infancy when it began to be researched by Mambro in his university library as a student. Vivaan soon learns as a writer and sharer of stories on the internet to write stories that offer the excitement of the ‘juiciest story ever’ by talking ‘about very risqué things’.[6] Mambro’s food as a student was the new American queer novel with the newly published English novel suppressed by E.M. Forster when he wrote it: ‘James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, E.M. Forster’s Maurice, Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar’.[7] When Mambro reads these he is able even to wonder ‘why these books were never mentioned at your school’, something quite alien to Sukumar ‘s expectations, untrained as he is by seeing queer films like Philadelphia, and better still, Fire, set in India not the USA.

Respectively these items available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philadelphia_(film) & http://www.impawards.com/1996/fire.html , Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4600450

What, after all does it mean to ‘own’ your own story and tell it: it usually entails a great deal of socio-cultural validation of stories through the media of one’s day, inbuilt by the psychosocial silences of that culture. This is why Sukumar never tells his own story but to one man alone, Mambro, his nephew, and its retelling depends entirely on the latter and perhaps even on the generation that follows Mambro in Vivaan. In my title passage above I quoted these pieces out of sequence. I restore their sequence here. When Mambro told the story of his Mamu, Sukumar, to his own nephew, the young openly queer young man Vivaan, he says; ‘I wasn’t close to him so I can only imagine and piece things together, …’.[8] The life of Sukumar is not ‘his own’ in this novel that honours him and the duality of his character is a construct of someone who heard him out but had to reconstruct him from his own imagination, filling in detail he could not know. And this detail is legion, for Sukumar must suppress so much, even under pressure from his lover, X. Even when je tries to tell his story to young Mambro, whose arrogance of youth even takes his wife’s side in the understanding of Sukumar’s divorce: ‘Alas words are failing him, his wisdom cannot be framed by the language he knows’. This life is not solely that of a victim however: ‘not a failed existence lived as marginalia; it sure had its moments’.

He can’t rewrite his life, it is too late for that, but might he compose a coda, one of his own making, in the words he knows best. Could a man like him be allowed that at least?[9]

This is extremely moving, though its metaphors for life are consistently not those we can safely attribute to Sukumar, but could to Mambro who tells that life to Vivaan for one of them to rewrite in this tripartite novel. Writers of novels are more likely to refer to life lived as marginalia to the main story or even to say ‘rewrite’ your life, rather change its onward direction. To rewrite means we get to control not only the events we narrate in the now, but those that happened in the past and which have already been metamorphosed as memories. And, though these may be frameworks for telling stories of life for Mambro, they are becoming so for Vivaan, and we have to remember that Mambro feels as unable to tell his own story too, if for entirely different reasons from Sukumar

‘I don’t think I can write about my own life yet, but I’ve written it all down. … It’s funny how I’ve been writing stories about other people until now …’.[10]

He can’t write about ‘his life’ but he has already written it down in the more private medium of handwriting. These handwritten (manuscript) pages have a tendency to be vulnerable to loss – their attachment to their sequencing is loose, and the novel ends with one of the ‘loose’ pages written by Mambro (or imagined as such if we think of Vivaan as the overall narrator of the collected documents of the story). It is near the end of the novel that Vivaan tells us that ‘Mambro told me his Mamu’s story’. Vivaan responds by taking the evidences upon which this story hangs to frame a ‘triptych’ (a three part piece of art) not unlike the novel itself in which not only the differences by the similarities of the three men are clear: In fact this triptych is a diptych: made up of two photographs of three persons: Grand-Mamu with Mambro on his knee at the latter’s annaprasan, and the other with Vivaan at his annaprasan on Mambro’s knee: ‘baby-me in exactly the same position’.[11]

Much in this novel continually makes itself known to Western readers as about rituals of living unknown to them, for which no explanation s given. Annaprasan is one case but much easier than other ones that test the Western reader to turn to a glossary- admit, that is , that in relation to Hindu or other Asian traditions, that they are the alien in relation to these beautiful life traditions. Much of Sukumar’s story delights in thus alienating white western readers with no machinery of notes or glossary to help them. In my view this is important. It raises the difficulties of reading between cultures and their languages that is raised again in the novel regarding changes in queer culture, even down to the languages that mediate these cultures. Sukumar’s feeling hat he has no language as a queer man is in part because his culture and languages as a Bangladeshi are marginalised but also because they are so by the onward movement of Indian culture into new forms through, in part, the reshaping of culture caused by new media and their distributive powers, especially up to the level of Generation-Z computer literacy. It is good for modern readers to feel there is that in Sukumar’s life that is valuable in its independence of the West, and its refusal to translate itself into Western terms.

But this too goes for how every adolescent learns the means of living in ever-changing queer cultures, and their fast-changing media representation. These changes are not merely from negativity to positivity – for in some cases the movement is backward – as in the tokenism of the culture of Vivaan’s school. In the school dance, for instance, though Princi (the Principal) adores the Western-type modernity of her stance to the ‘GAY COUPLE’, her school still forces the children into dance roles that are forever binary in their performance and in which both boys feel uncomfortable cast in the ‘Femme’ role.[12] This dance is so unlike that man on man dance that recurs in memory in the novel between Sukumar and Mambro – an Asian dance that does not require binary delivery through distinct male and female roles.[13]

But there is splitting of being across age ranges of queer men, sometimes by the names and labels felt acceptable. For instance Zee corrects Vivaan’s use of the term ‘gay’ as too non-inclusive, substituting, as was once the fashion, ‘men who have sex with men’.[14] Later Zee introduces Vivaan to sexual combinations that also do not exclude women, preferring the term ‘homoflexible’ for Vivaan, though allowing him to scroll other alternatives: ‘ pansexual, polysexual, queer, androgynosexual, androsexual, heteroflexible, homoflexible, objectumsexual, omnisexual, skoliosexual, bi-curious’.[15] In contrast Sukumar is thrown when his lover, now married to a woman, takes to calling himself ‘Homosexual’ as a new term. I remember Sukumar’s response well in my own past life:

X knew a lot about laws and rights. He called himself homosexual , a term that made Sukumar cringe, uncomfortable with the labelling of himself something so foreign and derogatory. “can’t I just be Sukumar?’” he asked naively.[16]

How naïve Sukumar actually was is tested in the novel’s telling of queer history, for during the novel queer culture begins to return to a version of this idea in Vivaan’s time, though without a distaste to labelling and the use of Western (Graeco-Latinate) terminology. The issue is not unlike the way that some Indian lives split anyway – as they are made to choose, by context of discourse, to write a language appropriate to a culture that you don’t like (‘English’ for instance). Later Mamu feeds his sister with English books, with English letters accompanying them despite the fact it was ‘a language you never speak with each other’, from which, presumably, she learns to call her brother and name him to young Mambro as a ‘homosextual’. I love that error that renders queer categories a product analogous to the ‘textual’. Mambro merely says: ‘that’s how she pronounces it, and you don’t want to correct her lest it break her flow’.[17]

That sociocultural models for sexual life are disabling is clear from the beginning. Even at the age of six , Mambro dreams of being in love with an adult male (in a scenario in a dream in which he is himself is adult), I remember a similar experience: it was one where love predominated over sexual contact but did not exclude it, though it was idealised as dreams are. The first pages of Mambro’s manuscript open the novel and they insist that the capacity to love precedes all categories of language and conceptualisation.

The man in your dreams is the man of your dreams.

…

The young man is wrapped around your senses, face radiant, eyes playful, fingers stroking the hairs on your forearm. The sky is a smudged rainbow.

And even though you’re only a boy of six, and everyone in your world is husband – wife – child, and you’ve never known a man to love another man, you feel love for this man, and feel his love reflecting on yourself, as though reaching across into the mirror, touching the face. [18]

This is a beautiful passage, but it proves nothing about whether the love is experienced as that of a man to a man before social categories for this kind of love are invented, though both Mambro and Vivaan want to believe it is and invent rituals and artworks to prove it. For Vivaan there is still the possibility that love objects can be multiple – perhaps homoflexible – and we have to remember that though the passage above purports to capture the consciousness of a six year old as a memory, it is an older man who writes this memory. To write, and then rewrite, may be to distort, even if not in a malicious manner. That dream is recalled again a little later in the novel, where Mambro insists on the interpretation of it that it is evidence that he is ‘into men’ and ‘always had been’: ‘because aren’t dreams mere manifestations of instinctual responses?’[19] The truth may be, as Zee insists, that to be a man and love other men is not necessarily an exclusive category but may be a choice or even, for some, a necessity of loving at all.

What we cannot expect of a novel is to solve this metaphysical dilemma for us. All it can do is show that it is not people that make some forms of love seem ‘dirty’ when it is but the shaping of it by sociocultural boundaries created for other means than as expressions of love or desire, just as Zed, is really created to sell commodities like unto himself. Zed justifies the commodifiable desire substitutes he can create thus: ‘The more human beings shun making meaningful connections with each other, …, the more they’ll lean on experiences like ours’:.[20] Yet these are experiences that mean that love will forever be a thing that seeks solitude not mutuality in the future, a relation with imagined words and pictures that are of things we think we like not new things we learn to like and be like and grow into.

Bhattacharya is some amazing queer novelist. There is something wonderful and new in all this beautiful and readable writing for our community and to raise our community into a realm others who think they aren’t like us will like. Do read it.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Santanu Bhattacharya (2025: 269, 268 respectively) Deviants Fig Tree, Penguin Random House

[2] Vivaan Name Meaning In Hindi: https://namealways.com/vivaan-name-meaning-in-hindi/

[3] Ibid: 190f, 284f.

[4] Bhattacharya 2025 op.cit: 170

[5] Ibid: 5

[6] Ibid: 81

[7] Ibid: 156

[8] ibid: 268

[9] Ibid respectively 275,277.

[10] ibid: 269

[11] Ibid: 269

[12] Ibid: 54f,

[13] See ibid1i90f,284f.

[14] Ibid: 10

[15] Ibid: 86. Look them up yourself.

[16] Ibid: 100

[17] Ibid: 194f.

[18] Ibid: 1

[19] Ibid: 32f

[20] Ibid: 240