Many of Iris Murdoch’s characters feel they are in a drama not of their own scripting (which, of course they are – as Bradley Pearson and Hamlet are in The Black Prince and Hamlet respectively and both together in the first) that can only be changed by getting out from under the net of a web of false relationships. This blog contains some thoughts on reading a play I had neglected by the great novelist.

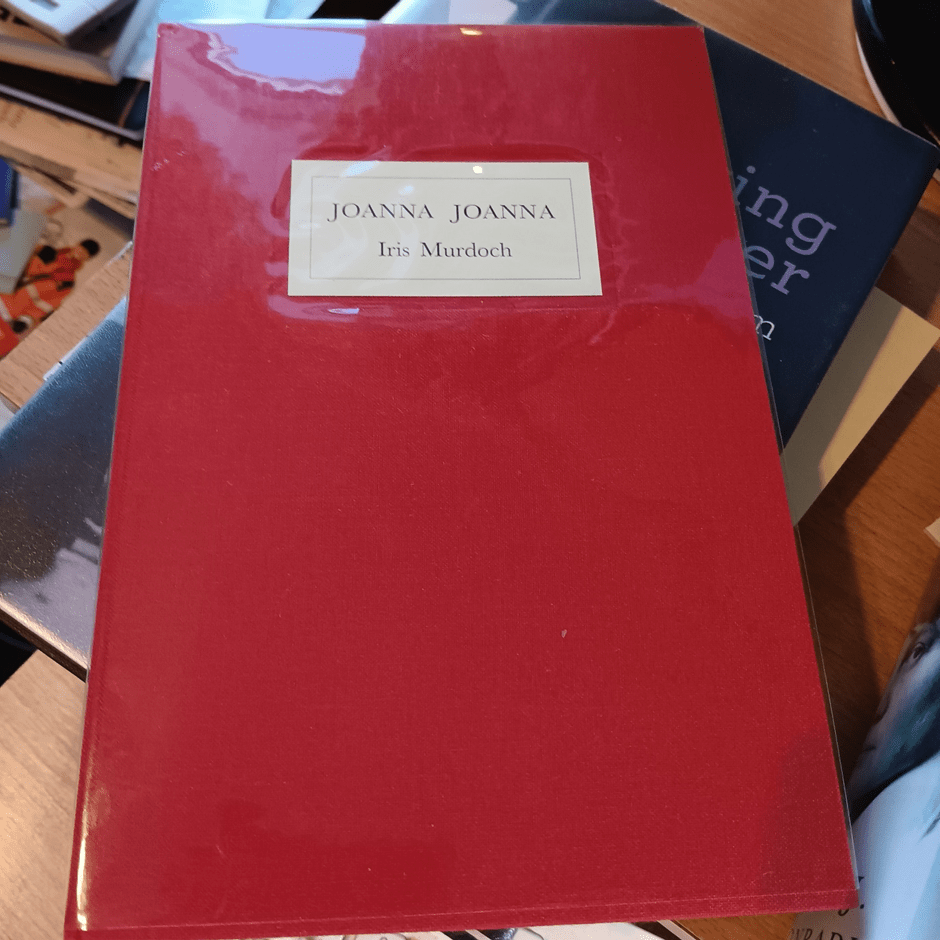

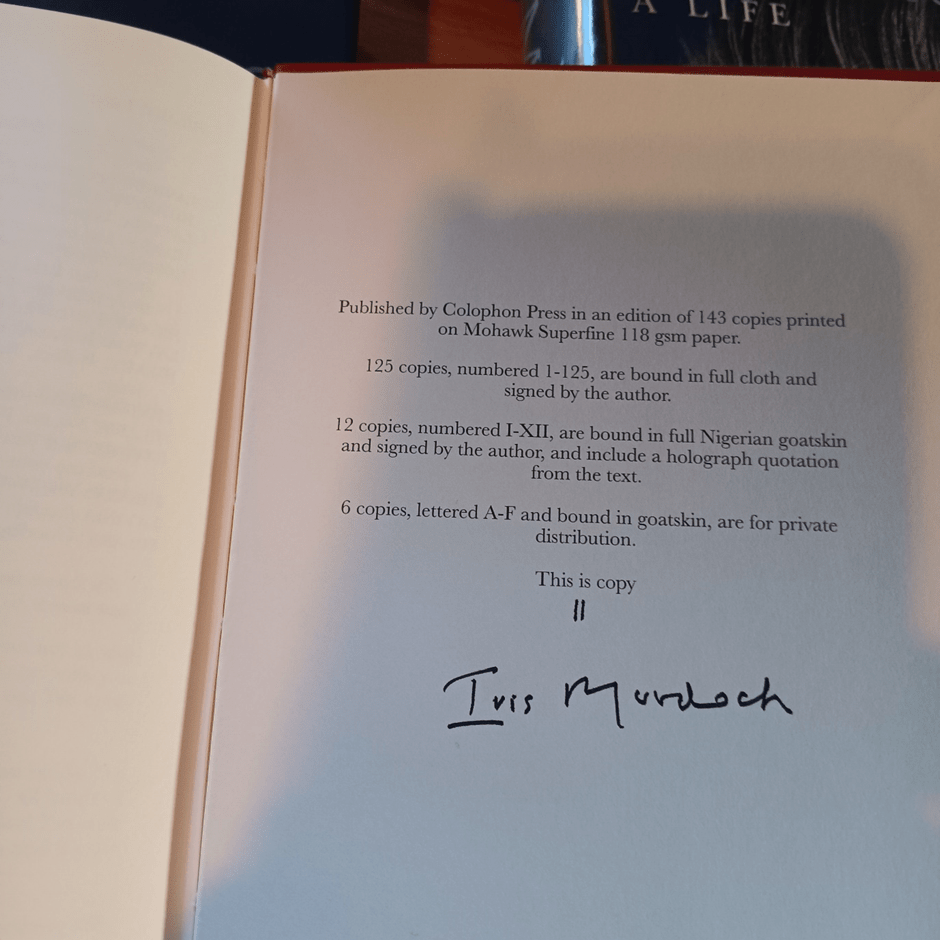

Last week I became aware of an app intended to allow a comprehensive listing of one’s own library and shortly afterwards I began to use it. It is going to take an age, for even though International Standard Book Numbers (ISBN) and especially digitally coded ones allow for easy searching, much of my collection has neither of these. Moreover I found that, as I approached my core collection of beloved authors, I occasionally find works that I have never read but always intended so to do. One such was a play named Joanna Joanna published by Colophon Press in 1994 with a limited run of 137 copies. My copy is number 11 of this edition and bears the bookplate of Woodrow Wyatt, once a left leaning Labour MP who later was hounded out of the party by Hugh Gaitskell for supporting individual ballots in secret in union elections and campaigning against union block votes) and who later became a fan of Margaret Thatcher for her attempt to control trade union ‘power’ as he saw it.

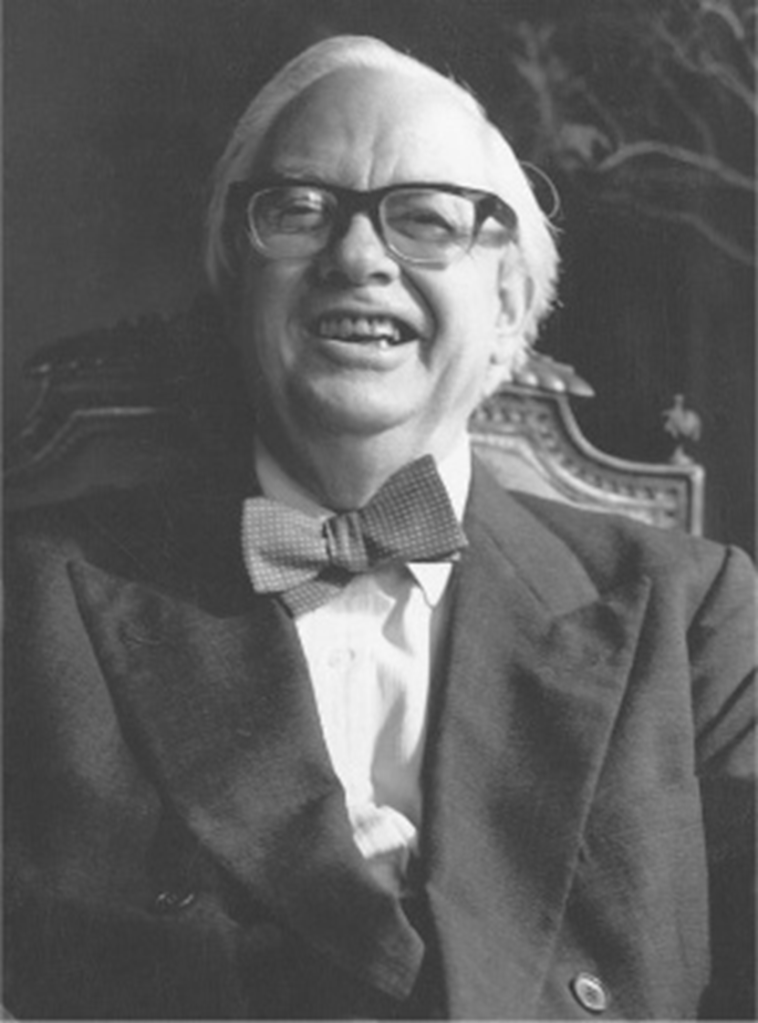

Woodrow Wyatt ASINB015QQ10FG, Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume Two: Everything She Wants

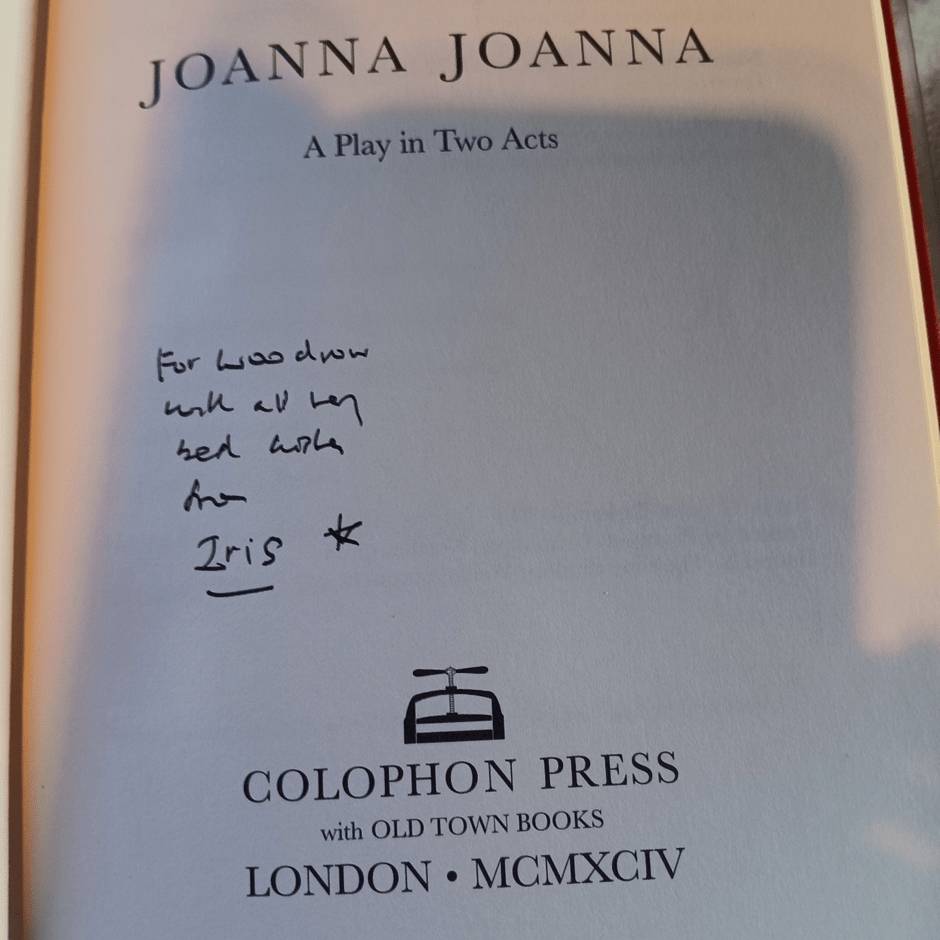

Wyatt was very much the kind of man Murdoch admired and this copy as well as bearing the standard signature on the limitation record page at the end of the slim book (87 pages) but also has a signature and dedication (;’For Woodrow with all best wishes from Iris – and marked by a hand-drawn star) as well as Wyatt’s personal bookplate on the fixed front end paper. I looked again at the book, neither remembering when I purchased it nor ever having read it.

Having now read it, I can confirm that this was for the first time and I determined to try and find out about it, even to try to like it. The Kingston University Murdoch archive tells me that the play was actually written in 1969, a fact confirmed elsewhere and that its name up to late in publication was simply Joanne.[1] Although an evaluation appears to be available from the Iris Murdoch Review (no. 12) of 2021, by Miles Leeson, I have been unable to order it or find it online. Nevertheless, having written to the author, I still feel I need to write out my response to this play. Peter Conradi describes her, as a ‘puritan who (J.B.) Priestley accurately noted did not really like the theatre’ but who ‘none the less craved theatrical success’. He points out her correspondence with Peggy Ramsey, the theatrical agent, who considered Joane Joanne to be unsuitable for the theatre because of its rapid changes of setting and scene and used arcane methods, such as representing a student riot by noises off. Murdoch would often assert that a ‘novel is a drama’, which rather reduces the role of an audience in immediate contact with embodied actors in the notion of what drama might be.[2] Elsewhere, Conradi says that the play was ‘(rightly) never performed , but the plot was stolen and improved upon in the novel A Word Child’.[3] Even Murdoch, having finished the play and determining to send it to Norah Smallwood said in a preliminary letter that: ‘This, you will be glad to hear, is my last offering to the future for the foreseeable future’.[4]

The play actually reads remarkably well, though that is hardly an adequate defence of it as putative theatre. It is, in common with her novels of the period, obsessed with the meaning of relationships and how these might be described in ways that distance themselves from normative value systems. The whole point of the play sometimes looks as if it wants to be a surreal fantasy imposed upon the structure of a conventional well-made play. There are at least three scenes where this is so.

- Act 1, Scene 7, page 46. In a drug-bound scene the music of a distant ‘college dance’ becomes a means of bringing together star-crossed lovers – a young professedly straight man, Teddy, in love with a straight girl, Lavinia, who is in turn in love with a young queer man, Gilbert, who is in love with the young straight man, Teddy. They dance around a narcissistic Texan youth in love with his punting pole, bringing together the domains of dance, boating and sex and uniting the trio of lovers around the totem of a phallus.

- Act 2, Scene 2, page 61. Here Lavinia and Gilbert tie up Teddy to take their revenge on him for breaking their circle of suffering and dissatisfaction by seeking sexual satisfaction from an older woman, a satisfaction he is denied by Lavinia and which he is offered by, but refuses, from Gilbert. The exchange of sado-masochistic playfulness becomes almost impossible to relate to motive. It is this which Teddy will call ‘’the last act of a very silly drama’, almost a self-reference to the play within itself.

- Act 2, Scene 6, page 74 and following pages. The rationalist Roger visits the queerest character of all, Kathy who believes herself to exist in a strange Manichean religion where seven devils and God define each other as one, time is a constant mix of past, present and future and her life heading towards that of the convent but represented by a figure on the end of a telephone, heard by all characters, who seems only to be pretending to be a holy Father. Crabtree the medic believes Kathy to be mad, but she herself seems tortured by a sexual situation in which her husband’s love is represented by his impotence, her passion for her stepson, Teddy, amounts to obsession. In this scene she manages to stop her stepson from sexual compromise with Roger’s wife by showing him what she knows (we see her learning the information by overhearing it in earlier scenes). But how this happens is by a fantastical magic fantasy centring on a crystal ball containing all time, the portrait of Joanna becoming flesh again and a series of stage lighting effects.

All of this shows a play that refuses to make itself realisable in the theatre and perhaps even in imagination. The stress on Kathy of all the themes she must bear means that just as she is about to be taken into a psychiatric ward, like Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire, but thinks she is travelling to a convent, a plane crashes near her , she collapses and dies. Clearly the play finds it difficult to balance its desire to elicit the queer illusoriness of a world without rational values and the need for them its characters all have, even Kathy – who at least wants a straightforward narrative of progress to the religious life.

We are never allowed to know if the plot that binds the three star-crossed lovers or that binding the dead and absent Joanna to Kathy is a kind of psychological syndrome about motifs of the angel and the ‘whore’, who refuse to be separated are forms of madness impinging on real life, or a real attempt to reconcile modern rationalism to images of hell, retribution and dark desires that represents the pain of rejection and loss, for which we moderns have no mythological or allegorical equivalence in our lives. Hence, the characters are hard to understand as people who learn.

The young man Teddy spends the entire play pursuing ‘heteronormative normality’. In the scene when he is ‘tortured’ for his attempt to break away from Gilbert and Lavinia and their maintenance in a threesome of the ‘sanctity of our suffering’, he says: ‘ I don’t know how you two manage sexwise. You’re a girl and you’re a queer. I’m a normal man and I’m twenty’. Yet that hardly describes his life either that name ‘normal’ .[5] To his later older female lover’s (that’s Jill) dismay he claims that he wants her, despite her greater age than he, because she makes him ‘feel so blissfully ordinary’! [6] Teddy will discover that he is queer, as Gilbert always seems to have known, only after he learns that three men have reason to believe they are his father, he loses the love of a girl, who is probably his half-sister, and only loves men she cannot have for some reason, and finally realises the problem in making love to a woman who may be his step-mother.

Yet is this the point of the play that is it is in the real world unplayable, unpresentable. Like many Murdoch characters, Teddy feels he is in a drama not of his own scripting (which, of course he is – as Bradley Pearson and Hamlet are in The Black Prince) that can only be changed by getting out from under the net of a web of false relationships – to mothers who are not mothers, lovers who might be sisters or fathers who might have any relationship to him. Once he discovers, always knowing his current Mumsie was not his biological mother, that the ghostly and absent Joanna who is that real mother had a past unboundaried sex life in which he had three possible biological fathers, he turns away from chasing normality and goes in a fast car to Italy with Gilbert. The candidates for father are Roger Saxonby (Joanna’s first husband), Doctor Crabtree and the man he thought of his father but whom his stepmother had told him (unbeknownst to her husband) as a child was not his father as ‘he never managed to make lover properly to Joanna’, Hilary Fitch. Fitch is impotent in every way except in a knowledge of academic theory. Yet Teddy still turns to Hilary who could not possibly have been his biological father, saying to him: ‘I love and admire you and I’ve lived happily with you all my life, we’ve been real friends, …’. This forceful making of a father out of nothing in his biology is tremendous:

You’ve been a wonderful father and I have always loved you and i am your son. There are truths which lie deeper than facts. You are my father in spirit and in truth. Actual paternity is just a kind of accident. Real paternity is – a real relationship – like we’ve always had – Dad.[7]

And this carving of reality out of the mutual attachments that come from nurture and culture is perhaps the point of the play, for culture allows for variables and subverts, as much as it constructs, boundaries and norms around relationships. The status of people in relationships is subverted. Age, sex/gender, state of mind nor class really fully determine prohibitions in relationships. They work if they work and if they don’t this may be accident not relating to differences in the partners. Jill tells Teddy he is a very ‘silly boy’ because he does not grasp that love is a variable not a constant: ‘Everybody goes on falling in love’ she asserts.

Ans, as superficial as Jill and her husband are, they act as if norms matter not a jot with their polygamous lives of multiple affairs. But Jill also knows a truth she can utter but not enact. Though she says love ‘is a great destroyer’ she insists that it’s ‘one of the great gambles of the world, one of the great life-changing hazards’.[8] And I am certain Murdoch embraced that view of the world. And I am certain of that because people who thought they had links to supernature and were superior to time always have (but it’s better done in the novels) to find as Kathy does that the only way she will ‘put away all hatred and pain’ is not to go to a convent as she thinks, or an asylum as others know will happened, but to find that: ‘I knew it would be now. My time has come’ and leave only by collapsing and dying.[9]

The others get into fast cars and change their sexuality or loosen their sex/gender identity or have open or secret affairs to pass the time with life-changing hazard. Or if celibate and impotent, like Hilary, they become social workers because the world has no space for the king of ‘good teacher’ and a man who cares for his learners, as the Doctor and his learners say he is. But no-one really escapes the ‘hell’ constantly evoked in this play, anymore than they do in Sartre’s Huis Clos. Because under the surface on which Roger and Jill live is ’some sort of private hell’, into which Kathy is plunged. That hell ‘makes her into sort of two people. She’s naturally a kind and gentle person – but sometimes she becomes absolutely demonic’. Doctor Crabtree medicalises that condition, Kathy herself sees it as supernature imping on her but Hilary knows it may just be that the fact that for some the boundaries never get addressed and the person is locked into pain by themselves by deliberating making the ‘Joanna thing into a barrier between us’. For some the barriers are necessary and that is the definition of a private hell.[10] For Dr Crabtree even ‘incest’ is no real barrier.[11] For Kathy her love of Teddy seems the thing she suppresses the most as if that love were incest, which, of course, it isn’t unless you are determined to construct that barrier between ages and social roles.

Having read this play, I do not feel I have progressed my understanding but I have at least played out some of the dissonances in Murdoch’s dance to the music of time;

With love

Steven xxxxx

[1] Peter J. Conradi(2001: 468) Iris Murdoch: A Life London, Harper Collins Publishers; Avril Horner & Anne Rowe (2015: 355) Living on Paper: Letters from iris Murdoch 1934 – 199 London, Chatto & Windus.

[2] Conradi op.cit.: 530f.

[3] Ibid: 468

[4] 16 January 1970 in Horner & Rowe op. cit: 384

[5] Iris Murdoch (1994: 63) Joanna Joanna (Act 2, Scene 3). London, Colophon Press

[7] Ibid: 82f. (Act 2, scene 8)

[8] Ibid: 48f. (Act 1, Scene 8)

[9] Ibid: 87 (Act 2, scene 8)

[10] Ibid 68f. (Act 2 sc.4)

[11] Ibid: 84 (Act 2, Scene 8)

NOTE: Milers Leeson kimdly pointed out to me how to access his article on the play. In it he cites this fascinating journal entry by Murdoch:

Jan 27

I suppose that I am trying to find how is a play: but a play

Is no good unless it is utterly [?] a

POEM. O let me find that, that.

One cannot be a utilitarian because of the absolute importance of

telling the

truth, e.g. finding right form in art.

Jan 28

The theatre: a place to act out one’s obsessions? Violence.

X [in margin] Rewrite JOANNA.

Feb 12

Haha. Completely stuck with play. Dust and ashes.

My efforts in the theatre have the formal stiffness of the juvenile work of

a painter