Name the most expensive personal item you’ve ever purchased (not your home or car).

Now the prompts from WordPress recycle and fresh questions do not appear, I have to answer the ones I rejected answering the first time round. Times like now when I have no project blogs ready to go, I pick apart the assumptions of these recycled ones as the only ones I am allowed to answer, despite the repugnance they caused in me.

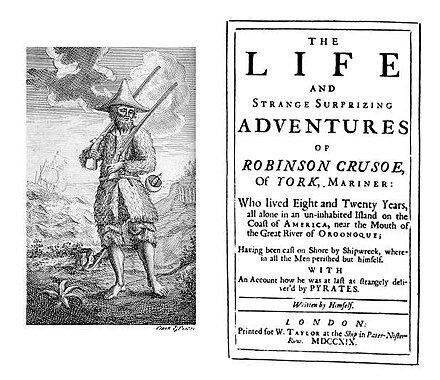

This one was probably the worst. I remember the shudder on first seeing it. Of course, it can be answered innocently. But that is only because its assumptions lie so deep in the history of the ideology of the ‘person’ as it is constructed in Western and Northern capitalist societies. In these ideologies, a person is a set of desires for things that will outwardly manifest their inner being and develop and grow that personal being. It’s model as an ideology of what constitutes self hood and personhood that is manifested best, as Marx brilliantly analyses, in the narratives he called ‘Robinsonades’, after those narratives of the eighteenth century best known in its finest literary version, Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe.

Even in the illustration from the firstvedition, Crusoe is characterised by the items he gradually finds himself able to acquire by expense of exchange and services or simple exploitation to remake the gentleman he believes himself always to be, a white landowner with a right to clothes and appurtenances, especially of self-defence, that characterise his personal independence.

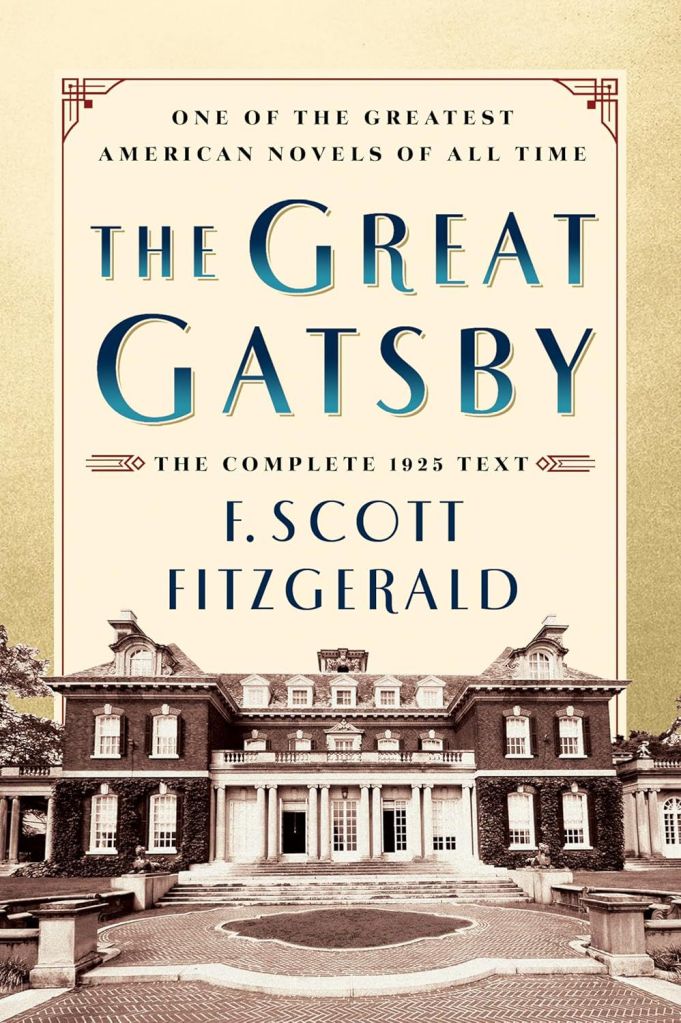

The prompt question says we must not count houses or cars as our most expensive personal items. I would like to think that that is because it is so obvious that homes and means of mobility that transform our time-space are clearly not solely ‘personal’ goods, nor capable of meaning outside their social role of having or not having them. But I think they are really excluded in order to avoid too many of the same answers. It is clear after all that both are brought by many people to manifest outwardly the sense of their own personal significance and to boast having sufficient financial means to afford their ‘expense’. There are many fine examples, the best being The Great Gatsby, in which an expensive house, car, and various ‘personal items’ that advertise conspicuous consumption are the man, the person Gatsby.

Why do we equate our desire to expend ourselves, strive to afford and be seen as capable of affording, the ‘expensive’ to develop and grow the idea of our person and self. The answer is not simple and involves the many ways in which the concept of a desirous individual being, open to the shaping of its ideas of ideal consumption by advertising, is essential to the capitalist myth that there is no such thing as society but only an aggregate of individuals forever formed to compete with each other, even in the ways they consume and manifest self to others in expensive jewels, clothes, personal accessories – guns in the USA – and other trappings.

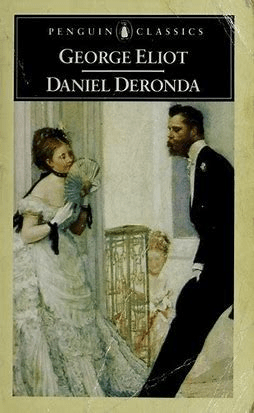

The person becomes thus the things they are seen with, the closer to them the better, like the diamonds Gwendolen Harleth wears in her hair – the symbol of being bought by Grandcourt and the true belongings of another enchained woman – in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda.

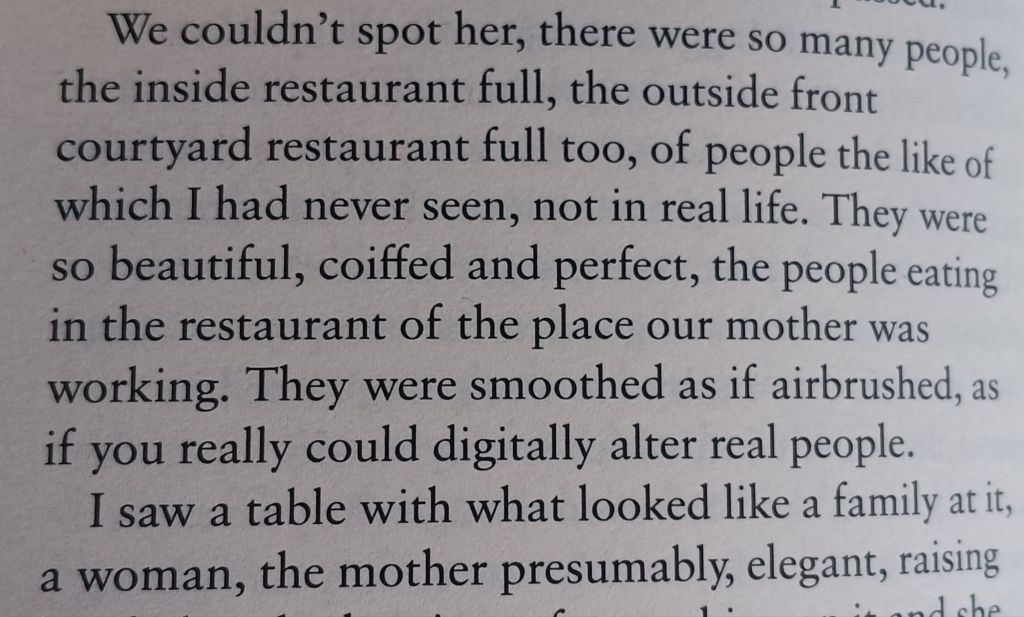

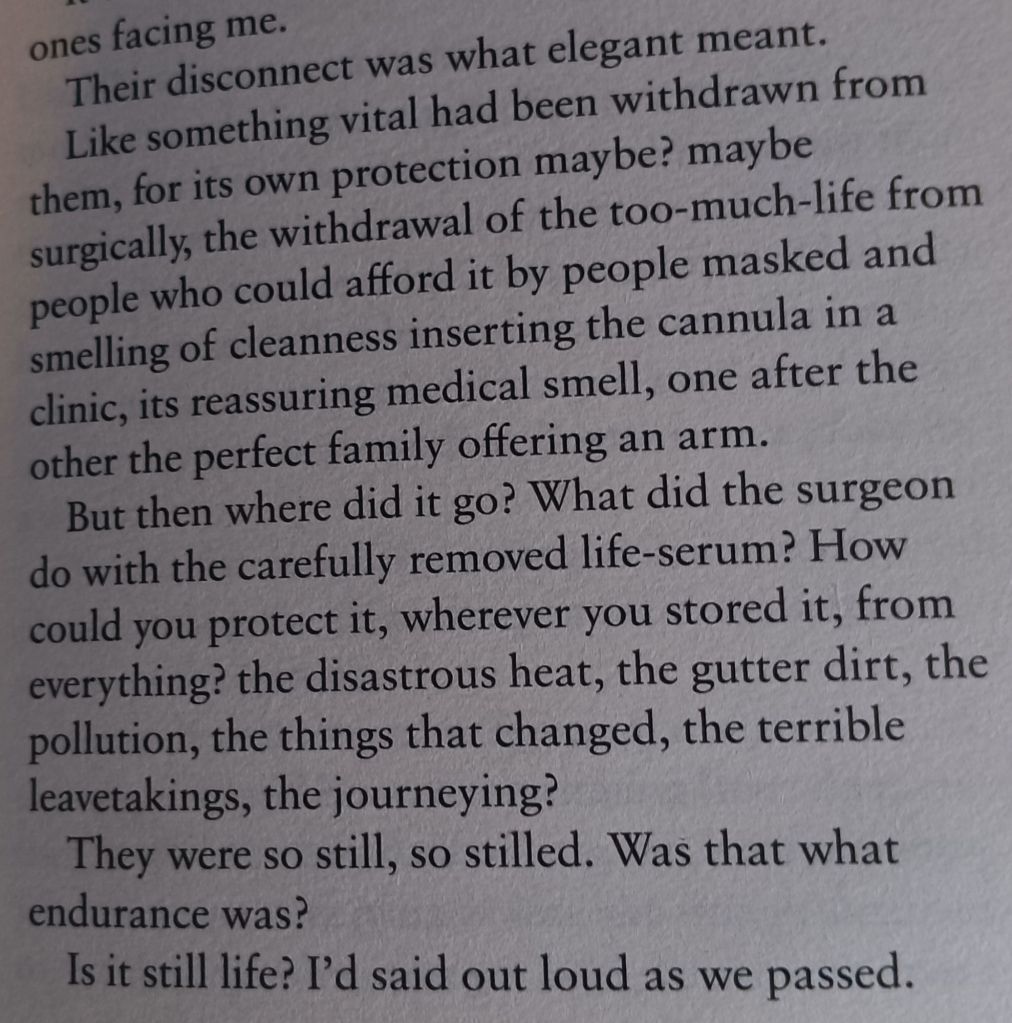

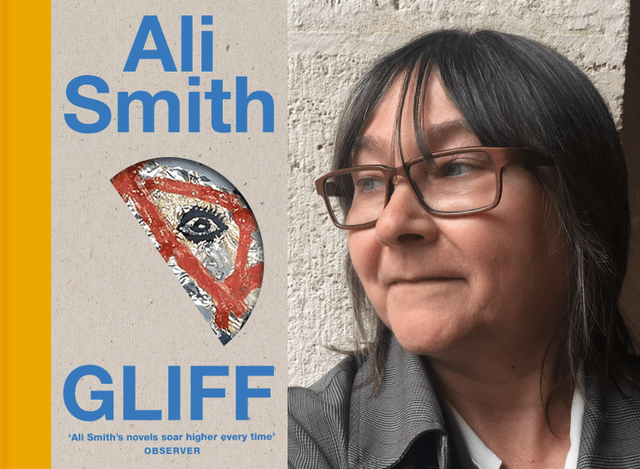

The project of my next blog is Ali Smith’s great new novel, Gliff. She, as always, covers everything. In its opening a family of ‘unverifiables’ in a future society that defines with red marker people and things that cannot be made to fit the tyranny of its expectations of consumer acquisitiveness, views a hotel in which the ‘unverifiable’ mother of the family works. They see rich verifiable persons. The person’s viewed are their personal items alone, they and them having had any real ‘life’ sucked out of them, as in the two excerpts below from pages that ought to be read in full (pages 6 and 7 respectively):

If we allow our life-serum to be sucked into our appearance, we become the ‘elegance’ of our personal items, a still life, stilled and never motivated again. I can’t wait to write properly on Gliff properly.

Of course no-one is FREE of the contradiction by which commodities define personhood in a complex networked capitalist society (no less is Ali Smith – although she offers imagined escape and some civil resistance). I spend too much money, often that we don’t have, on expensive books. But they above all are only ‘personal items’ in a slight way – for they are a portal to more, especially if shared with each other. but contradiction, contradiction, contradiction … ever contradiction”

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx