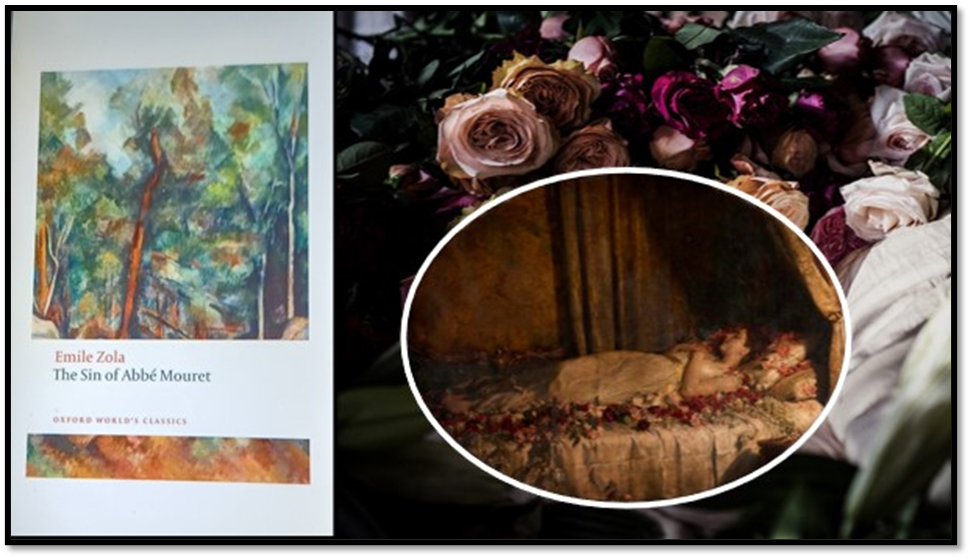

Bridging Gaps in Personal Learning: This blog is an attempt to understand my own process of learning. It is based on a highly situated and contextualised reading of Émile Zola’s The Sin of Abbé Mouret (La faute de l’abbé Mouret) translated by Valerie Minogue (Oxford World Classics ed.) Oxford, Oxford University Press, an edition recommended in the essay by Julien Domercq (2024) ‘The Montmajour Drawings Series: Between Observation and Imagination’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) (2024) Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, London, National Gallery Global Limited, 56 – 65 and in between visiting that Van Gogh exhibition and an equally innovative one, with one eye on Van Gogh as Bacon’s model as a colourist, at the National Poetry Gallery (the blog on that exhibition to follow).

The attention of the later nineteenth century to this novel might be represented in the pictured Pre-Raphaelite ‘The Death of Albine’ by John Collier (1850–1934) (the detail from it is in the white bordered oval, the painting is in Glasgow Museums) whilst that of the twentieth century in a feminist conceptual new film, (surrounding the circle) by Rebecca Louise Law named ‘The Death Of Albine’). Albine dies by suicide facilitated by overwhelming herself with the scent of multiple flowers from the garden in Paradou (the scientific-modern & traditional symbolist ‘Paradise’ of the novel). The Oxford cover of this translation uses Van Gogh. That suggests a much deeper engagement with Zola’s contribution to the theory of the Naturalist arts, which should not be confounded with social realist arts, as it often is.

This is the remit I set myself for this first of a few blogs:

| Topic | Comment |

| Re-reading Van Gogh’s method through Zola naturalism as a means of bridging the symbolist and observational perceptions of the drivers of physical nature in humans and in the flora and fauna of human nature’s context. Why this must evoke the religious model and revise it | Ambitious. Will it work? |

I think the essay in the Van Gogh catalogue insufficiently theorises the significance of the Zola novel. Domercq calls it ‘a modern reworking of the Fall of Man’ and although his description implies that much gets changed in the reworking (including the re-calibration of the relationship of the ‘pure’ and the ‘wild’ from a religious to an evolutionary model), they never say so explicitly.[1] Much better is Valerie Minogue’s equally simple summary: ‘… Albine and Serge will play the central roles in Zola’s version of the Fall of Man, a version quite other than that given in Genesis’’.[2] Valerie Minogue traces in her Introduction ways in which the roles of Serge and Albine are like those of Adam and Eve (in the search for a ‘forbidden tree’ for instance) but it is clear that these figures cannot alone account for the roles the couple fulfill, with each other. Eve, for instance, in traditional iconographies is redeemed by Mary in Christianity and further enthroned in Revelations as the ‘woman clothed in the sun’. Whilst Albine can take on all these roles, at least in Serge’s conception of her, her closeness to primal nature is not fully captured in the ways Serge wants to conceive her as a model of ‘purity’.

Hence my need to make those issues of the naturalisation of religion significant, for the term ‘anti-clerical’ on its own oversimplifies Zola (and van Gogh’s relationship to spirituality and religion). ‘Paradou’ in this novel is a modern relativist Paradise imagined as if it were the Unconscious, where time and space expand with desire and contract with forces that militate against desire, including sublimation. Van Gogh himself was deeply aware of this, setting the conditions with which the garden at Montmajour, a ruined ancient aristocratic power-house like that in Zola, that he visited with Milliet (the model for his portrait The Lover) fails exactly to fully represent an idea because its size is so finite.

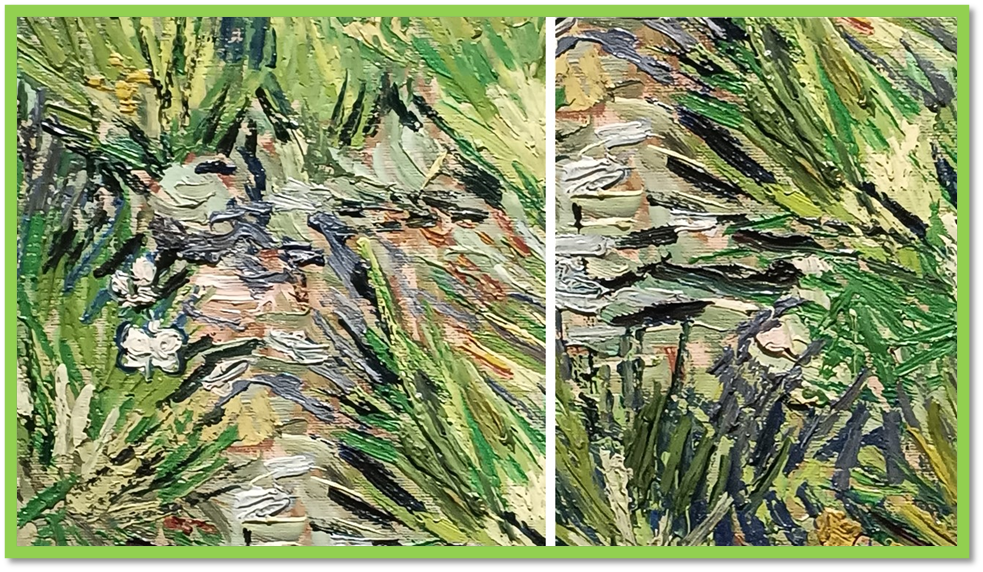

Hence he never drew it, drawing instead the more malleable dimensions of the landscape views it offered of the natural world as it encompassed Arles in the distance. Yet he allows the viewer’s eye to be drawn into the detail of undergrowth in the Montmajour / Paradou setting such that perspectives are confused and a whole mass of detail in an undergrowth expands to fill our minds, exactly as in Zola’s Paradou. Van Gogh intends us to be drawn in to the undergrowth and its wild patterns and dynamic markings of varied intensity and depth to show the difficulty of transfer between close attention to nature and its transformation into landscape adaptable to the human town beyond. Size matters here and is as confused in its dimensions as that written into Serge’ and Albine’s days at Paradou where what seems contained suddenly grows with your desire to explore it more intricately. This is and is not an allegory of the couple’s sexual explorations, when they are not disrupted by human and institutional constraints, those which seek ‘purity’ of a religio-human construction rather than drowning in the passions of wild nature that submerge human identity in arcs of fertile pleasure.

Keep looking at that wild configuration of markings that evoke snares and depths without any immoral intention in their keeping the eye focused but rather what the Paradou looks like to serge as he is healed from his breakdown by Albine. She flings open the window of his close sickroom to shoe “The Paradou! The Paradou!” And we fall into markings by words that both enlarge our vision and contain it in itself, not looking out to purely human constructions of order:

It is asking a lot that I ask others to try and see synaesthetic similarities between Van Gogh’s drawing, less so when we look at his colour impasto, and this prose, as strong in this English version as the French. The aim is to create a land governed by wildness accommodating only the sun, as Dionysus (or Hyacinthus) might accommodate Apollo, a thing where light and shade are not binaries but variants and seas, deserts, fires, orgies and animal life (all called wild at times) become one expression of another kind of purity, from the stiff purificators, starched by the grim servant to the clerisy, La Teuse, in the early part of the novel. Look again at Van Gogh’s impasto detail from the painting Long Grass with Butterflies (1890). Is there not synaesthetic correspondence? I think there is.

The issue in Zola’s novel very much addresses the notion of purity as humans conceive it- anticipating ideas in Freud later, as Minogue says, but also Mary Douglas’ Purity and Danger, who, as an anthropologist examines the relevance of purity and purification rituals in various spatial-temporal contrasting cultures. In Judaeo-Christian and Muslim cultures historically purification ritual has hung around the notion of the unclean woman and this too is a feature in this book, which opens with the old, fat peasant woman (how she describes herself) La Teuse insisting that she is a service celebrant of Mass with the abbé preferable to ‘those naughty boys who laugh like heathens’ ‘ When the appropriately named example of such a boy, Vincent (how Van Gogh would have laughed to read of this ginger-haired look-a-like from a notorious family quite unlike his own) comes init is to La Teuse sore at the idea that women are soiled goods relative to young boys – impure in ritual service: ‘Come on in, you naughty boy, since Monsieur le Curé is afraid I might soil the good Lord’. [3]

The uncleanness in woman is associate with menstrual blood in Jewish ritual and blood here sometimes serves as an impure excrement with others. Set against the original sin of Eve is the immaculately conceived, according to Counter-Reformation Catholic ideology, and conceiver of her son Christ, Mary, unstained by any sexual contact with men. Yet Mariolatry is for the stern Archangias a step too near the impurity of women and he warns Serge Mouret of the dangers of his fascination with this whiteness and supposed purity as precisely that, a step towards sexual attraction to women, who have ‘damnation in their skirts’. [4] Serg’s feeling for Mary is ambivalent as he kisses her white foot in his ravished delight in the immaculate purity of Mary’ [5]. indeed in one phase of his love for Albine, she becomes a type of Mary in his mind. The pure and the impure are in constant interplay, either consciously or unconsciously, even in Serge’s various dreams of emasculation (as the ewe lamb of the Lord’ for the ‘man in him had been killed” [6].

None of this stands still as a set of ambiguous feelings and desires. Before he falls ill he felt feminized, …, cleansed f his sex, his odour of masculinity. …, carefully purged of human filth’ and yet absorbed by ‘going into’, as a priest must, ‘the most monstrous cases of unnatural passions’ that one day might ‘cover him in mud’. [7] These moments are forever associated with the smell of goats and include not only bestiality as a potential but are a symbol of males accepting sex as a woman might (in the crude eyes of this medieval religion). His most ‘obscene vision’ was in his training where he sees a gargoyle, ‘in the cloister of Saint-Savourin in Plassans, a stone goat fornicating with a monk’. Hence seeing the goats his sister (Desirée – desire itself) keeps in her small holding, he ‘protected his cassock from the approach of their horns’. [8] Those horns are decidedly phallic.

The unclean and impure is a concept framed by the ordering force between it and the cleanliness and purity. Hence the novel starts with cleaning processes and the eradication of ‘stains’. It is tied in but not simply to other binaries like insides and outsides, female and male, wild and tame but there is no easy equation between each binary. We have seen that impurity in Serge, if not in Archangias, the curate, confined to women, although Serge will let this fantasy grow in Part 3 where he returns to his role in the church and even turns his primary adoration in ritual from Mary to Jesus. Zola is precise about fetishistic sexuality and there is a lot in the novel about the excitement evoked by the touch or feel of fingers. The first is early and has a kind of queered element in the ritual of purification followed by Serge during Mass, including the use of purificators to clean the cruets serving the Blood and the Flesh of Christ. There follows an element that seems to have been added to the ritual by Serge himself wherein:

he had Vincent pout tiny streams of water on to the tips of the thumb and index finger of each of his hands, to cleanse himself from the slightest stain of sin’. [9]

And then the sun breaks into the church and sets it aflame. Desire is sublimated in such imagery. At the level of this sublime imagery and sensuality the binaries stop working to frame pure from impure, the sacred an the profane. In Paradou with Albine the touch of fingers is embedded in sacred sexuality that has already bound purity into the agency of fingers that release showers of the flower of desire:

Higher up, at thew touch of her fingers, roses showered down, their broad, soft petals having the exquisite roundness and the scarcely blushing purity of a virgin’s breast. [10]

Later the same imagery used of Vincent’s careful work on Serge’s fingers is attributed to Albine, when Serge says in protestation of his love despite her feeling that he does ‘not love’ her ‘any more:

Never have I desired you so furiously. for hours, i had your living presence still before me, tormenting me with your supple fingers. When I closed my eyes, you lit up like a sun, and enveloped me in your flames …’. (11)

There is a lot more to say about the Zola novel but I think I will limit myself know to making the bridge back into the common synaesthetic effects that Van Gogh could be taking from this in Zola. Zola is a naturalist reliant on observed reality but the process of realizing that reality in representations necessarily invokes imagery that ranges from real to fantastical and mythical. And this is where I think, as a result of seeing the Van Gogh exhibition in London now and learning of the debt in particular to this Zola novel. Let’s take this painting, Undergrowth (1889). This painting feels both fleshy in sensual, cognitive and affective ways. Its dark patches read symbolically as something quite uncanny in the registered sensuality of the tree bodies and the bends into embrace in attraction and then into repulsion from each other. Judy Sund argues that Van Gogh’s rehabilitation in Saint-Remy mirrors Serge’s at Paradou possibly purposefully on Van Gogh’s part.

He doubtless noted this overgrown enclaves similarity to Zola’s Paradou – … . Memories of Paradou’s ‘green alcoves’ ‘made for embracing beings’ would account for Van Gogh’s charcterisation of the hospital garden’s luxuriant undergrowth as ‘nests of greenery for lovers’. Zola describes the ‘hidden hideaway’ in which Serge and Albine make love as a nook enclosed by ‘thick shrubbery’, where ‘there was only greenery , no patch of sky, no glimpse of the horizon’ and compares it to ‘an empty bedroom, in which one could sense … an ardent coupling’. [12]

Now it is usual to attribute Van Gogh landscapes entirely to observation or sometimes, in these pictures to sense something of his troubled mind. But rarely are they seen as I see this as a kind of moral landscape that like the passage referred to in Zola, plays with the interaction of sex, nature, power (including gendered power) and a complex poetry of attraction and repulsion, where love is not always innocent and may have reason to ‘hideaway’ is it seen as a place in which people acted in closed and secreted ways with not even a ‘patch of sky, no glimpse of the horizon’. I think neither Zola nor Van Gogh know how to think about coupling so ardent that it shuts out the light of the world and obscures colours that must be as hidden as the hideaway, but looking at this picture is not just a visual event – it involves registering feelings of comfort and discomfort, anxiety and desire, repulsion and attraction. The trees themselves are both beautiful and sinister. For Van Gogh like Zola and Serge, living in a Godless world is a difficult thing. And painting, even painting, is not ethically neutral as no art object that animates desire can be.

Have I met my remit:

Re-reading Van Gogh’s method through Zola naturalism as a means of bridging the symbolist and observational perceptions of the drivers of physical nature in humans and in the flora and fauna of human nature’s context. Why this must evoke the religious model and revise it!

Bye for now,

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Julien Domercq (2024: 58) ‘The Montmajour Drawings Series: Between Observation and Imagination’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) (2024) Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, London, National Gallery Global Limited, 56 – 65

[2]Émile Zola (2017: xviii) The Sin of Abbé Mouret (La faute de l’abbé Mouret) translated by Valerie Minogue (Oxford World Classics ed.) Oxford, Oxford University Press

[3] ibid: 6.

[4] ibid: 25

[5] ibid: 69

[6] ibid: 21

[7] ibid: 87 – 88

[8] ibid: 53

[9] ibid: 9

[10] ibid: 117f.

[11] ibid: 271

[12] Judy Sund (2024: 94) ‘Van Gogh’s Lovers’ in Cornelia Homburg (ed.) (2024) Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, London, National Gallery Global Limited, 80 – 97

One thought on “Bridging Gaps in Personal Learning: This blog is an attempt to understand my own process of learning. It is based on a highly situated reading of Émile Zola’s ‘The Sin of Abbé Mouret’, translated by Valerie Minogue”