‘The fear of being powerless. The fear of being watched and judged. The fear of infection. They blur together. The mysterious American disease has grown larger and more ominous in your imagination as it begins to spread in Britain. … You read about it in the Mirror and you kept the paper afterwards, hiding it at the back of your bedside drawer, unable to throw it away’.[1] This is a blog reflecting on the concepts of the imaginary that constitute the interior space of Black masculinity as five different Black men through history experienced it. It is discussed by Ekow Eshun (2024) The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House. I intend to concentrate on the intersections of Black and Queer masculinity in the life-story of Justin Fashanu.

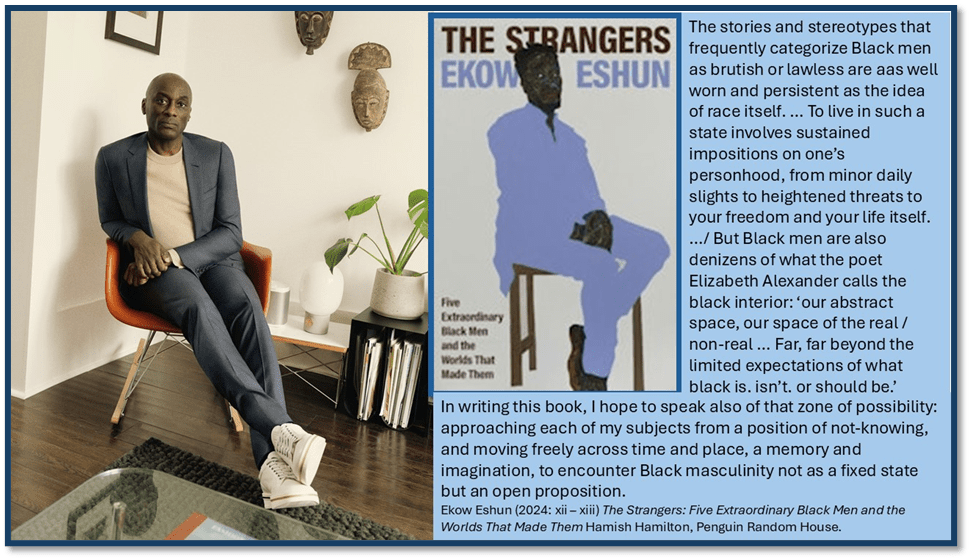

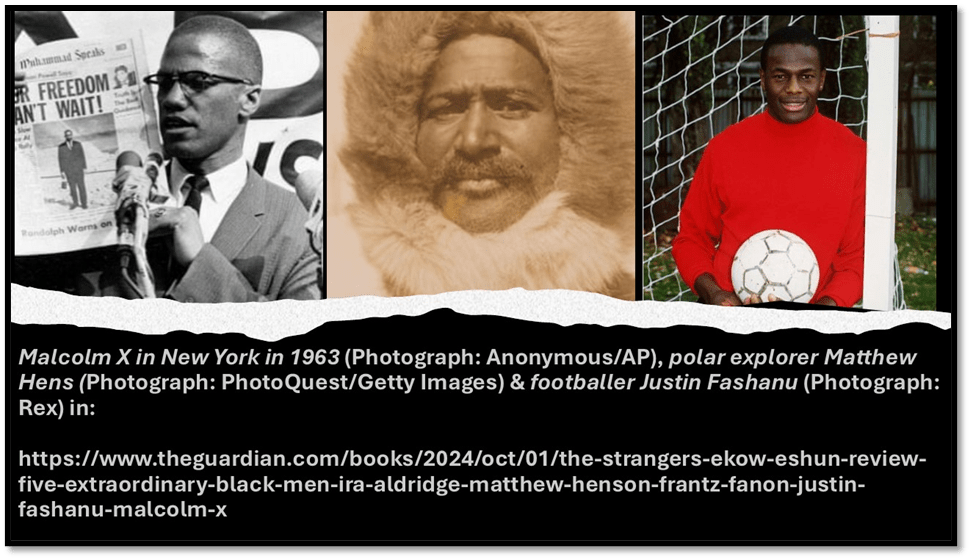

There is a lot to say about Ekow Eshun’s brilliant book, The Strangers, as a means of changing the landscapes of the biography of Black Men in history, especially when the stories of their lives have either been marginalised, as with the eighteenth-century actor Ira Aldridge and the early twentieth-century polar explorer Matthew Henson in the very different times and places of their operation in history, or misrepresented, but almost certainly both misrepresented and marginalised, as if each process fed the other. Hence, while most people have a memory of Malcolm X, for how many is this history anywhere near comprehensive and based on much but stereotypical pictures of an icon to admire or despise or both.

Likewise I felt I lived through moments of the history of Justin Fashanu (19 February 1961 – 2 May 1998), as the first male footballer to publicly declare his queer sexuality and his almost classic denigration as a sexual predator of very young gay men, leading to his suicide. Even as a white gay male, I had a relationship in my own interior space with the life of Fashanu, most of it imagined by the press or in public talk amongst different communities, including queer ones, and, in a more complicated way, by myself, for though I was not a footballer or interested in football, this guy was seven years younger than myself, and providing a lead at the time in the modelling of ways of coming out as gay or queer. What I didn’t know then was that both he and brother John were both care-leavers, and thus marginalised in this way too, and dealing with the public and private imagination that people have of public child-care and the reasons some were forced to experience it.

The Black Imaginary has some real evidence in its support that Eshun uses in the case of the actor, Ira Aldridge, for the latter became known as the first black actor to excel as Othello on the American and British stage, a role that exalts in the Black imaginary. Othello’s tales of his knowledge of the world even mirrors some of the more lurid graphic and written representations of the Black, and indeed Oriental and the Arctic, regions of the world and their peoples, in the late medieval Mappa Mundi in Hereford. Interspersed with the narratives of his wonderful Black men, told from their point of view but in the grammatical ‘second-person’ (you) not ‘first-person (I), are essays which detail how that imaginary was represented . After hearing from Iraas if from himsel, we hear of the treatment of the ‘monstrous races’ in the racial iconography and topography of Mappa Mundi. Othello tells of (Act 1, Scene 3, 162ff.):

… my traveller’s history, Wherein of antres vast and deserts idle, Rough quarries, rocks, ⟨and⟩ hills whose ⟨heads⟩ touch heaven, It was my hint to speak—such was my process— And of the cannibals that each ⟨other⟩ eat, The Anthropophagi, and men whose heads ⟨Do grow⟩ beneath their shoulders. These things to hear Would Desdemona seriously incline. But still the house affairs would draw her ⟨thence,⟩ Which ever as she could with haste dispatch She’d come again, and with a greedy ear Devour up my discourse.

I do not believe that the choice of Ira and the concentration in his story on his admiring rivalry in enacting the role of Othello as well as did Edmund Kean (4 November 1787 – 15 May 1833) – but as no white man could – matters in terms of the reception of the idea in terms of the Black imaginary. It is an idea from images in Othello and Mappa Mundi revived in the white press in ways that impinged on real Black men. A letter from a ‘lady’ (a white lady of course) sent to the manager of the Leeds Playhouse, John Henry Alexander, expressed her ‘revulsion’ at Black actors playing Othello. Ira was shown the letter. It sums up a level of popular white thought, nut Ira is reported to haave laughed at it. The ‘lady’ says:

A full-blooded Negro, incarnating the profoundest creations of Shakespeare’s art? One’s spirit cannot accept it? The African jungle should have been filled with the cries of this black, powerful, howling flesh, not the Leeds Playhouse.[2]

But this book is not about these men considered in isolation, as if the racism of the world was for each peculiar to their own spatial-temporal place and had no trans historical commonalities. The book makes trans historical connections throughout. Here are the opening sections (‘Ira Aldridge / Monstrous Races’ ) as described by Christina Fryar in The Guardian:

After each long chapter comes a shorter essay, where Eshun combines his own personal history with an eclectic exploration of Black history. In the essay that follows Aldridge’s chapter, for example, the author considers the Hereford Mappa Mundi, a medieval map that describes African and Asian groups as “monstrous races”, sketches out the final 20 years of David Oluwale’s life before he was found dead in Leeds’s River Aire, and recounts the time a journalist mistook him for a different Black man. [3]

Each of these sub-stories communicates by reverberating the deeply tragic story of Oluwale with that of Aldridge (and with perhaps the black men who became part of white society as possible models of Othello did in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries) with each other. But it also associates these stories with the mechanisms of micro-racism (the fusing of Black male identity into one whole in white eyes for instance far too often which leads to false identifications) interact, and how these interact with larger facets of racism, sometimes without the author drawing the lesson themselves.

The association with the wild and savage was a feature of the Black imaginary as the hegemonic White west saw it, even when tempered by a contrasting mythology of the noble Savage (present in Spenser as much as Rousseau). And this imaginary was a feature in the way each man, whose story is told in the second-person, confronted racism in each his own time with varied nuance and application, right up to Justin Fashanu where banana imagery would be used to type both his racial and sexual history (as a food of apes or as an emblem of a blowjob respectively) in the jeers and gestures of white male football ‘fans’. I want to concentrate on Fashanu.

Christienna Fryar summarises Fashanu’s story thus:

… Fashanu’s promising football career fizzles out under Brian Clough’s indifference toward him at Nottingham Forest and the stifling homophobia of Britain in the late-20th century.[4]

But that summary over-simplifies and perhaps stereotypes in itself the profound and many faceted analysis of the footballer’s life, including its contradictions. Brian Clough is indeed the monster of this story and a monster for whom the word ‘indifference’ does not at all capture the essence of what the existence of white working-class heroes meant to Britain at the time, which far extends the evil of which he was capable beyond anything to be accounted for by his problematic personality and sense of aggressive entitlement. Clough represented a no-nonsense ‘realism’ that, with a working man’s supposed bluntness, refused to accept that racism, homophobia and heterosexism were real issues except for the governing and institutionally educated, and could with that belief in himself as a ‘truth-teller’ just see Fashanu as a willing product of the commodification of football talent, black or white, gay or straight, whose role was merely to score the goals he was bought to produce in the interests of his employing club.

Fashanu’s story is the most moving in the refusal of his white colleagues to even notice racist and later homophobic chanting and its effect on Fashanu’s ability to self-create an imaginary person full of positive rather than negative potential .The use of the second person comes strongly into its own in such descriptions:

… the dressing room after matches is the worst, Your teammates never mention the insults and the spitting. Don’t they notice it, or do they just not care? They talk endlessly about the game and the ref but their silence on this topic is pointed. The experience is yours to bear alone. With each game your confidence dissolves further, washed away amid their indifference?[5]

This is where Fryar may have taken the word ‘indifference’ to characterise the worst thing facing Fashanu. But this would be to read without the access to the unspoken imagination of the self who uses ‘you’ to name themselves. The point about it all is not what these men, or Clough, feel about you, but that you must ‘bear the experience alone’, of feeling their behaviour and variously interpreting it. From such isolated imagination one often dreams the worst. It is indeed the source of the most terrifying dreams.

These dreams speak not only of queer back male experience but of the commonalities between Fashanu and other Black footballers of his time, including brother John. For men learn to know and feel interior space as a result of all the components of their world frame to them to know and feel. For Justin this was not only because of race and sexual identification but because of being a survivor of the care system in a Barnardo’s home and with largely kins white foster parents. In the care system boys survive by taking on the persona of a fearless man, not speaking that which pains them but feeling it none the less. It causes a ‘stammer’ in brother John. The advice ol;der brother, Justin, gives him (giving it himself in the term ‘you’, of course, also) will be fatal for their later relationship where John defends himself against association with a queer brother by manly defiance at a point where Justin can no longer harden himself:

You were his interpreter, guide, protector. Don’t let them see you scared, you told him, although the truth was, everyone was afraid. The crime is not to feel it but to show it. That’s what prompts the older kids to go marauding room to room at night. They’re hunting weakness. You have to pretend that you’re a man already, impervious to pain.[6]

This is fine prose. The ‘you’ given the advice is only ostensibly John Fashanu. Its main recipient is Justin, who therein cuts off what might have been his support in a more honest relationship to John, if such was ever possible – as men and brothers open about their feelings. This is a lesson Eshun learns. He appends to Justin’s story one about himself. Hardened against fantasy in day-dreams, Eshun is tortured in dreams at night with varied fantastical content, though much referring to racist threat> The dreams have a key antagonist, a tormentor whom he must learn to be not a devil but himself, actually appearing in the role Justin tried to take on for John , and with salutary intentions; ‘interpreter, guide, protector’. That men even need such a model is hard to admit for all the men in this book, even the almost saintly Franz Fanon. But certainly Malcolm X.

For me reading it, the interesting complication is Justin’s imaginary connection to the very real threat of HIV infection at a period in his own life that I remember so well in mine. Hence the quotation I use in my title- here again – but fuller and with the connection to Clough, where ‘indifference’ is the least of what he shows to Justin, but something more malevolent in the imaginary that it sparks in Justin and more terrible than the nasty piece of work that Clough was, as a ‘man’s man’:

The memory of Clough’s slap is impossible to get out of your mind. You brood on it for weeks, resenting the contempt in the gesture, the indignity of it, and your powerlessness to retaliate. In that moment he could have said or done anything he wanted and there’d be no way to defend yourself. He reminds you of a staff member from the home who would reach out and flick kids on the head for some perceived slighting of the rules. …

The fear of being powerless. The fear of being watched and judged. The fear of infection. They blur together. The mysterious American disease has grown larger and more ominous in your imagination as it begins to spread in Britain. … You read about it in the Mirror and you kept the paper afterwards, hiding it at the back of your bedside drawer, unable to throw it away.[7]

The treatment of men by men is ostensibly the subject but its true subject is the power of the imagination in you to interpret the slights men give each other (white to black mainly in the book but not only) as meaning so much more. Not even contempt is enough to fulfil that imaginary. In Fashanu the real events of the world get translated into huge proportions of imaginary strength, but partly because they are elevated to that position in social imagination – the fear associated for instance to infection and contagion, the bond between the oppressed and the moral panic to which they are too often associated – in the form of a fear of contagion with disease, and by wildness, darkness, enslavement and appropriation by the other. That other is the Imaginary Other having the most fearful of proportions – the content indeed of Othello’s stories and inhabiting the uncivilized margins of the Mappa Mundi.

As a young man I knew, without understanding, the effect HIV discourse (often misleading and unnecessarily punitive) had on me by the yoking of heterosexism, homophobia and the moral panic over infection during the epidemic at its worst and incurable, where many died, For Justin that gets tied to the way Blackness too is signified as ‘dangerous’. I think these deep waters surround the map of the minds of Black men in this book, though in various different ways and with different outcomes – not tragic at all for Fanon, but certainly so for Malcolm X, reviled by his own Black brothers, even Mohammed Ali.

And so it is no wonder that the imaginary is released from rumination over a ‘slap’ from Brian Clough, the meaning of which gets interpreted mainly in the lonely imaginary of one who must feel the meanings possible without support, and without even any true knowledge of why there is no support for him. Fashanu never realises the possibility of a positive imaginary like others in the book but for him it is imagined by Eshun as relating to a memory of a moment of longing and for the return between two men of ‘candour in your eyes’. For others the end of the book leaves such an imaginary open: ‘the unscripted, the always-possible. Even now, some bright future forming out of sight, coming into reach’.[8]

Do read this beautiful book. You will be love it. Just be open to its candour and gateway to the imaginary, even the scary imaginary.

With love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Ekow Eshun (2024: 340) The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House.

[2] Ibid: 37

[3] Christienna Fryar (2024) ‘The Strangers by Ekow Eshun review – inside the minds of extraordinary Black men’ in The Guardian (Tue 1 Oct 2024 07.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/oct/01/the-strangers-ekow-eshun-review-five-extraordinary-black-men-ira-aldridge-matthew-henson-frantz-fanon-justin-fashanu-malcolm-x

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ekow Eshun op.cit: 329

[6] Ibid: 299 (my emphasis)

[7] ibid: 340

[8] Ibid: 355