“Do your parents know you are gay?” “They’re village people.” “People can surprise you. …”.[1] My name for this blog is Regions, towns, cities, identities and village people: Determining the nature of Community. In this blog I interrogate the decision of the Durham Book Festival to entitle a session on new novels by Andrew McMillan and Tawseef Khan Writing the North. The novels considered were Andrew McMillan’s Pity (2024, Edinburgh, Canongate) and Tawseef Khan’s Determinations (2024, London, Footnote Press) I attended the session on Sunday 13th October 2024 at the Studio Theatre in The Gala Theatre, Durham at 2.30 p.m.

I sometimes feel sorry for Andrew McMillan who has to see me at so many events in which he discusses his art. I have already seen him speak about Pity at two events already, one at Whitley Bay and another at the Edinburgh Festival – where he appeared with Jon Ransom (see my blogs on those events if you wish at the links on the event names above). However, this time I saw Andrew’s talking of his great novel Pity with a debut novelist whose non-fiction work I did not know previously. His presence was endorsement enough of writing I ought to know. I decided to go to the event only on Saturday 12th October to make up for the disappointment of the cancellation of the Alan Hollinghurst session on that Saturday. I ordered Tawseef Khan’s Determinations on Saturday on my Kindle as a result and had read it before I left for the event.

I could not put that novel down. As I admitted to Tawseef when he signed my copy (for I bought a hard copy too) this novel felt to me like the equivalent for our age of Jane Austen’s Persuasion. He, like Austen picks a word that both characterises the plot and the notion of character and its content. The whole substance of Persuasion is based on a fictional history of the choices people make and the kind of persuasions that lead to those choices: whether they be the persuasion of authority from above. For instance, the decisive persuasion of Anne Elliott by her female mother-figure Lady Russell, that she did not, in her financially vulnerable youth, marry a man of so uncertain fortune as the young Captain Wentworth.

Anne Elliott learns from events, and the conduct of others, eventually the settled self-persuasion to accept Wentworth on his later proposal. Austen may ring changes on the ethics of accepting authoritative persuasion but the novel does not contradict the fact that elders often know better. The fact is that by the time Anne persuades herself to accept Elliott, he is established in rank and wealth and not the man of no fortune but in his unclear prospects from which she was, I think the novel concludes, rightly persuaded to refuse. As a young man no mere sea-captain, however apparently worthy to rise in rank, would have been yet established nor irreversible. The point is that theme of ‘persuasion’ in Persuasion is that of how life-choices are, and normatively should be, determined.

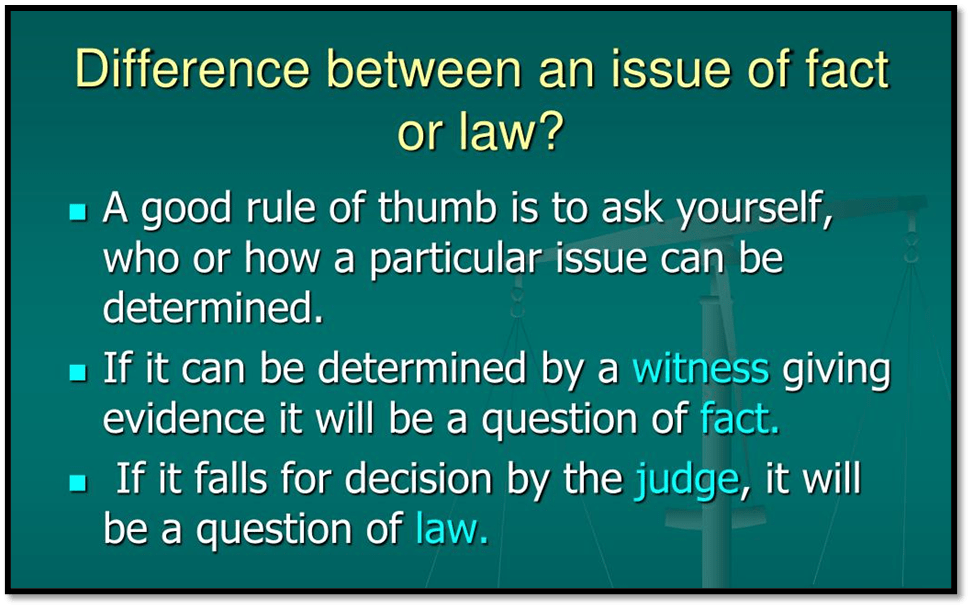

Tawseef Khan make the focus of his novel the ‘determinations’ that English courts pass down to asylum claimants. These documents of legal outcome bear the judge’s decision and reasons for that decision in asylum cases, and we actually read a full determination of the fictive case of John Kulasingham (based on real enough cases from Khan’s own practice, as Chapter Three of the book.[2] Others follow for other characters equally arbitrary in the judgement of the circumstances of real people. Part of one other, that handed down to the character, Khalil, we read together with the perspective of the central character Jamila, an asylum lawyer. She concludes that the ‘determination’ made was based on the Home Office having given it ‘a superficial glance’ before it ‘then proceeded with its ready-made conclusion’.[3]

Given that there are many such determinations in the stories of the asylum and refuge claimants in this novel, the nature of the word itself gets focused so that thew actual term need not be used. Like persuasion, determination is an ethical quality that motors decision-making into action as well as a result, for instance faced with friends she has neglected, Samir and Maryam, it ‘took a degree of determination to walk over, especially as her instincts compelled her to leave’.[4] Determinations are not merely outcomes of decisions, they are moral qualities and forces within persons that do not necessarily match the instinctual, nor the institutional, ready-made scripts for our behaviour. They determine how people place you ethically as well, as in the case of asylum, determining the possibility of refuge or not in the UK.

Jamila Shah, for instance, has to have it to defend her authority for instance with both staff and clients. When Sadia accusingly says that Jamila is ‘not married, are you’ in order to challenge her view of the position of women in it, she knows that her argument must stand and so: ‘she tried again, caution in her voice, but also a good deal more determination’.[5] That may, I have to admit exhaust the uses of the word in the novel Determinations – although the same applies to the word ‘persuasion’ in Persuasion. The word matters less than the theme it promotes and the structures of behaviour, thought and action it describes. What matters in Persuasion, is what the forces are – external and internal authority in the balance – that persuade towards any decision, not only of marriage. In Determinations too the issue is how are decisions determined and, in extension, what forces internal and external to the person the decision most affects contribute to it, There is a huge problem when the state alone, and the forces of a ‘hostile environment’ (Theresa May’s words) it marshals to predetermine cases in its favour.

But the issue that Determinations truly has as its focus was named in this event by Tawseef as ‘community’ in answer to a question from the very good interlocutor (Professor Naomi Booth, the Head of Durham’s University English Department it seems) about the attitude of both novelists to main characters.

Neither Pity nor Determinations truly has a main character, both novelists admitted, and in both novels characters are often forced to articulate their own autonomous viewpoint against the noise of other voices, jostling to be heard. As Tawseef Khan says the solicitor Jamila’s office is an ideal disrupted quarrelsome focus of contrary voices, from staff and clients, that add up to so much ‘noise’ that must continually be interrupted if anyone is to be heard. In contrast the Home Office speaks its self-determinations in brutal sole authority without giving chance of effective interruption, except by the highly determined, as Jamila must be.

In Pity the equivalent to this community focus is the working men’s club and the ‘gossip’ it contains (well barely contains – it spills out everywhere in the town).[6] Contrasted with this business in which the need for formal carers to give caring families a break flows into witness of possible homophobic violence are other more regulated but transportable temporary communities such as those of the academic community who descend on Barnsley, with a poet very like Professor Andrew McMillan (the author allows that uncertain identification) in tow to cast a perspective on contemporary Barnsley from the outside, with at least the look of authority as they pontificate on the meaning of ‘Community’.[7] Perhaps one of the most moving moments in this event was when Andrew spoke of bringing his novel to the writer’s own home-ground community of Barnsley as ‘coming to terms with my own outsideness’. Attached to this is the awful dialectic in the novel in the choice of its sons and daughters to leave or to stay. Andrew chose to leave, if only to Manchester (near enough) but the distance is not only in miles. The novel lauds those who stay and narrate Barnsley in a different way, like Simon with his version of Thatcher.

What determines the person’s wishes to live or not amongst a certain community (whether a community of place or identity) is then at the centre of both of these novels. Those determinants include the means by which they will do so (by finding a ‘living’, in the case of asylum seekers following determination of a ‘right’ to make a living in that community) and the power and personal resources to implement these personal decisions. But note that in both the interest is in not just communities identified with place, location or ‘setting’ but with identity. Of course the two elements of our notion of community are in continual dialectical co-formation, emerging hopefully as third terms like local queer communities with fuzzy edges with the other elements of community in which it is in friction and coalescence (both remember).

Andrew McMillan uses his characters Simon and Ryan but also Simon’s bisexual father (his bisexuality still dawning), Alex, who must move beyond his own mining father’s values without losing them and be a little more ‘visible’ than he likes as ‘Simon’s dad. Puttana-as-Thatcher’s dad’.[8] I think then it helped the interlocutor started the event by asking about the ‘settings’ of the novels comparatively, although I think we needed setting to be inclusive of communal elements not conveyed by the idea of place or ‘locus’ alone. For both placing community has much to do with the idea of where conventionally literature takes its setting.

Just as Andrew McMillan avoid the setting of urban Manchester, with its pretensions to being a cultural hub (to say nothing of London for choosing the North itself is a step beyond convention perhaps – of which more in summary at the end of this blog), so Tawseef told us that eight years ago when Determinations was in planning (or ‘determination’) it was to be set in Bethnal Green where his solicitors’ practice then was. He recounted the resistance in himself to setting it in Manchester and how he overcame it. In Manchester, he could map his characters location in the various villages and small towns that once were independent of the conurbation as it is now – with those names that ring with associations of all kinds for Mancunians like Ancoats, The Northern Quarter, Chorlton, Didsbury, Stockton and, of course, the Gay Village (where ideas of community of identity and place are meant to meet – for some).

From top left clockwise: Didsbury, Chorlton, The Gay Village (Canal Street), Ancoats and, finally Rusholme. All in ‘Determinations’.

Community of place has very porous boundaries and internal differences in both novels. Barnsley, for its modern characters, if not for the first generation of miners in it, extends to he pubs in Sheffield where Simon enacts Puttana and on various train routes travelled between places with distinct meanings. In Determinations the characters live are located in places whose meanings differ t them hugely and significantly. These are only extreme in terms of differences between South East Asian setting and British ones in , for instance Nazish’s comparison of herself as a factor in the communities of Wilmslow Road, Rusholme (that’s in the bottom right picture above) and the Swat Valley in North Pakistan where her grandmother lived till her death, a comparison Nazish only makes when her grandmother dies, thinking of the safe refuge she found with that grandmother.[9]

Swat Valley

But communities of identity matter too – to Nazish who is even urged by her family, other than her grandmother, to go to Britain where her life as a lesbian might be accepted (only to find that isn’t entirely the case) or my own favourite character, Zulfikar, whom Tawseef at the event described as unfinished business, someone requiring better understanding than in this novel, in perhaps another later novel.[10] I don’t agree for to me the partiality of our grasp of Zulfikar’s identity matches his own far less educated and developed grasp than Nazish of her own (wonderful character though she is), partly as a matter of differences between the characters of class and education if not of race, religion, though certainly of culture (that between Pakistan and Bengali Bangladesh – a cultural difference that was the site of bloody wars of independence).

For instance I title this blog with a particular favourite quotation of mine that comes when Henry, his putative English ‘daddy’ (an older richer man who likes younger men and is prepared to ‘keep’ them), looks to the commonalities in the experience of gay men testing out family support. They have this conversation:

“Do your parents know you are gay?”

“They’re village people.”

“People can surprise you. When I came out, it divided my lot. But I expected them all to reject me”.[11]

Of such conversations queer community, indeed at its best, is made. But, Henry, a union man, does not, as I do, react with humour to Zulfikar’s phrase that his Bengali family are village people – members then of the agricultural poor class in Bangladesh, with memories of that sign of queer identity that was the pop group called Village People.

I expect however the highly educated Tawseef Khan did – though he did not confirm that when I asked, though he smiled. In many ways Tawseef must feed a lot of the energy that goes in the intersections of identity (both entitling in our society and otherwise) through the character of Jamila Shah. She continually kinds to refine identity out of categorical labelling, around the term ‘Muslim’ for instance. But she also has to fight the labelling of her sexuality as queer because she fights queer cases and one of her best friends, Shamir, is an openly queer male. Nazish, who is deeply unsure of her identity of place identification, perhaps even of ‘race’ has no doubts that she identifies as lesbian and wants everyone else to be clear in that category saying to Jamila, even using the incorrect label, Mrs, which is, Jamila tells us elsewhere actually a label of professional authority and a ‘mark of respect’ in the community of South East Asian asylum-seekers and therefore ‘she resigned herself to a title and authority that wasn’t really hers’.[12]

“Actually, Mrs Shah, I never understand this. When you represented me, I was always wondering, what does she like? Boys or girls? Everything or nothing?” Nazish asked.

Jamila’s smile disguised her irritation. It wasn’t an especially novel question … nor did it offend her. But there was something about its entitlement, its claim to know who or what exactly powered her desire that didn’t feel … right. Some rooms in her house were locked.

This is not just about a desire to remain ‘in the closet’ in any way but a resistance to categories that are strictly unnecessary. That the locus of the object of her desire was locked away is not to maintain secrecy but to defend the right only to open up queries about oneself one wanted to open and met your needs not those of others. The issue is precisely about the right to self-determination, a right that has to be extended to Tawseef too precisely because this novel must have opened up many worm-like enquiries as to his sexual identity. That he dramatises them in a woman is important but not as a defence but to show that it is more than the British Home Office who sometimes want to close down what sexual (and gender) identity actually means to the person embodying its repertoire of variations in themselves.

Jamila is unhappy, as is Zulfikar that other queer men tell him how to prove his queerness to the Home Office to gain asylum – ways alien to his character as a former ‘village person’ from outside Lahore, like making an explicit gay sex video of himself with a man. As much as this is not Zulfikar’s manner of queerness, he is also quite unlike the flamboyant Western queer identities played with by the group, The Village People in the collage above (bikers, sailors, Cowboys and Indians, construction workers and so on …).

Lets’ return to that point because, whether the play on the word village (in the name the group from the USA it originally signified the gay area of New York, Greenwich Village). It little matters whether the play I referred to was intentional on Khan’s behalf or only my own. I think it a good example nevertheless of the interaction of queer communities of identity and communities of place. In fact neither community is a community of the homogeneous but of massive differences – even beyond the fine class differences and obvious racial ones between Henry and Zulfikar. That is so in the ‘villages’ that make up Manchester and are neither just Mancunian nor another thing. That is clear in the novel, when people utilise location boundaries. But it is also true of the Gay Village in Manchester (focussed on Canal Street modelled on the example of Greenwich). It is largely a haunt these days of hen parties and sightseers, but even before that happened it was a community full of divisions as well as unified support between them: – a ‘village’ sometimes (but not always) with the heart of a stony oppressor as stony as the outside world to some differences of self-performance:

Each time Zulfikar went to the Gay Village, he felt horse galloping in his chest. On previous occasions he’d hidden among his acquaintances, but now he studied the crowd: men making eyes at each other….

Forced by his friend, a former asylum seeker the one who recommended making the sex video, Kehiru, to dispense with a baggy T-shirt for appearance was not Zulfikar’s aim, put on Kehiru’s ‘favourite tye-dye shirt’, presumably tight and be sprayed with CKI. But why should Zulfikar be a clone of Kehiru. In the end it is because the Home Office demand it in order to meet their identity stereotypes – and that include active sex, for they have no concept of the queer otherwise.[13]

Communities of identity cover a lot of ground explored in both novels of identity (through class, work role – miners, police, drag queen), group social identities of place or venue type (clubs for instance), sex/gender, sexuality, race, culture, nation etc. etc. … Pity explores the Maurice Dobson Museum – a former miner who set up a grocery shop with his male lover in 1956, ‘at a time when homosexuality was illegal’. Dobson wore women’s clothing and explored his sexuality with enough support from his local community to male it viable. That different communities meld in the one former mining village where Dobson set up house, household and made a living runs counter to the notion of homogeneity even in the intersections of a villager. What matters about a community is ‘the importance of who is tells the story’: the story constituting its ‘creation myths, of the importance of a place telling the story of itself’. What McMillan insists that there can be communities of place that intersect communities of identity, in which both the place and the identity will look different in differently determined accounts of it.[14]

It begins to feel as we explore that there are important commonalities in these two very different novels about very differently created and configured assemblages of both different and some similar identities that each novel has in its full repertoire – and both have VERY FULL repertoires.

And if we return to the interlocutor’s question about the importance and significance (or otherwise) of main characters, I think both novelists ploughed a similar furrow in their answer, although very differently expressed. Andrew McMillan said that Pity was neither the kind of novel of carefully and highly controlled structure in its narration and plot. He allowed it to jump about, change focus – not only in the eye used to see things but the kind of seeing instrument (from the recorder used in Simon’s sex work online, to the cameras Ryan works with – even those focused on a well-known ‘cottage’ – a public toilet used for sex between some men) as a security officer aiming to join the police, to the academic reports and ‘fieldnotes’ written by the academic researchers, to the ordinary gossip as it varies between work, leisure and other communities. Andrew at one point called Pity a ‘deeply unethical novel’, but, as he went on to clarify, that was because it refused one central source of ethical authority such as we expect in novels with an omniscient narrator – Jane Austen or George Eliot.

Both novelists spoke of their discovery when writing that conventional novel structure failed them, a point also made by Hollinghurst as I suggested in my blog on him (available again at that italicised link). It has a particular resonance in the life of queer characters (as Naomi Booth pointed out). By ‘queer characters’ I mean anyone who refuses to tell a story of themselves determined by some authority that claims to know them better than themselves. This is every character, apart from a few of the entitled – strangely including Kehiru in some respects, to ape a stereotype in the knowledge that this has benefits to them at least in the short term. It links to the demand in both novels for areas of invisibility in character and even of place that don’t get seen (a point made much more subtly than I can make it by the panel). And it includes buried material just as the private lifes of the generation of Barnsley miners Andrew writes so beautifully about in his poetic flashbacks to them. Their poetic nature (I saw this for the first time this time) is part of their abstraction from a knowable detail. Take this one (the italics are the writer’s):

He steps out into the long corridor of early dawn; wind galloping past him. Above, the sky is moving quickly and three doors down Pat is just closing the front door … The village, on their shoulder now, still asleep, not watching the migration of tired bodies. One of the men said he thought he could hear the coal cracking. Another man told him to stop talking daft. …[15]

I have never dared ask Andrew about an echo of Tennyson I hear here of In Memoriam (lyric cxvii).

Doors, where my heart was used to beat

So quickly, not as one that weeps

I come once more; the city sleeps;

I smell the meadow in the street;

I hear a chirp of birds; I see

Betwixt the black fronts long-withdrawn

A light-blue lane of early dawn,

And think of early days and thee,

And bless thee, for thy lips are bland

And bright the friendship of thine eye;

And in my thoughts with scarce a sigh

I take the pressure of thine hand.[16]

Andrew reading – he took the invitation to read from the lectern.

Nothing can be further from McMillan’s context – a middle-class gentleman thinking he might hold the hand again of a male friend long dead, all played out against what is made invisible and internally secreted but for that ‘light-blue lane of early dawn’. How close or otherwise is that from McMillan’s ‘the long corridor of early dawn’? Perhaps not near enough but what these passages are about are what the men in the mines gladly, perhaps without knowing, suppressed from themselves and others – not because they were repressed queer men but because their life was constrained all day in long corridors underground: ‘Dark like the bottom of the ocean’.[17] It is the same cusp on which male friendship is on the cusp of desire, a handshake of ‘holding hands’.

In Khan’s novel Jamila Shah slips from being the central focus of consciousness and ‘point of view’ in some narrators to becoming a named (as Mrs Shah) or an unnamed actor as seen by her staff or her clients. Here is the view of Sadia, a member of staff, but introducing her husband Akbar, to the office to see if it competed with the law firm for which he worked (with Mustafa), though (unbeknownst to her) only as a clerk. She looks differently at it as if from the imagined point of view (as a novelist would) of her husband (whom she doesn’t really know as well as she thinks): ’She hadn’t liked what she had seen then – seen through an outsider’s gaze. The office was small and untidy. …’. But that view transforms even within one paragraph until she sees it just in the way that Mustafa claims to see his own office but which she had thought a delusion:

It was a temple. A Sunday school. A community centre. Akbar’s reverence of his boss had been a mystery, but with time she understood: the work had a spiritual dimension. If Mustafa was a visionary, then Mrs Shah was too.[18]

Tawseef reading – he preferred to sit.

And for Akbar, or so his wife Sadia thinks (for many points of view are not approached directly in a way that validates them), the point of view he begins to fear, when he loses his post and, it seems, his wife (who is now staying with her parents) is that of a traditional Muslim community. Why does he hesitate outside the house when visiting Sadia. Nobody will ever know?

Was he worried about community? Did he fear the emasculating power of their words, if they learned he was to become a ghar-jamai, a man who lived with his in-laws? As he stood there, was he weighing up the pros and cons, calculating if she was worth it – or was it a question of courage?[19]

Pity is not the same kind of novel, but it has communality with the story of Nazish who is the only character who reevaluates Britain and Manchester in such a way that she would rather return to stay in Pakistan, whatever its effect on her freedom as a lesbian. Much of this needs rethinking by me but when Andrew talked about the way a community represented ‘home’ or not, he invoked an idea used by the academics in the novel of home communities being ‘bound up’ with grief and nostalgia that the academics explain as ‘inherited trauma’. None of this can be resolved – academic and psychoanalytic discourse in the novel like all academic discourse in real life has no more authority than those it seeks to interpret are willing to give it, for right or wrong. But I think the two novelists certainly seemed to feel there was material here from which to consider themselves singing from the same hymn-sheet (a deeply inappropriate and cliched metaphor in this context – LOL!).

Tawseef spoke of the deep question not only of a notion of ‘home’ that was not ambiguous but also of ‘refuge’ or ‘asylum’. For concepts we find comforting in the abstract never are when realised in our own specific circumstances. Concepts like these were written in a generalised schematic mental playscript that pays no attention to the complex and contradictory conditions that actually determine our lives and our decisions about how to survive circumstances and make a living in them. . Tawseef said that to seek ‘home’ and / or ‘refuge’ is to seek it in places and communities (of identity and place) that begin a series of questions about what home means rather than being an answer to the question: Where can I find home / refuge?’ Andrew McMillan insists that things may be different for entitled white people in a hegemonically white culture and that there is no easy translation between issues of staying with and telling different stories about how narratives of ‘home’ might work in a complex world. This could be, he suggested, because the white people in his novel never have to submit the things they wish to be visible of themselves to an authority capable of totally invalidating any other story than one they want to recognise as the story of the asylum seeker in a necessarily (as they see it) context of a ‘hostile environment’.

I cannot end however, without at least a paragraph on why the two writers were advertised under the rubric ‘Writing the North’. My own feeling about this is that the notion that the North has to be rescued from invisibility in writing is perhaps a double-edged sword though I agree entirely with Andrew McMillan and Tawseef Khan that there are forces on writers to believe writing can only sell in English-speaking culture, or indeed have literary quality rather than a sociological or propaganda one, if set in the South of England. That indeed must be contended with the representatives of some of these forces in critical journalism, the academy and publishing but at the level of readers I think it is a mistake to think it is they who resist the North as a theme, or if so only at the level of readers in some of the institutions I have mentioned as being reactionary forces. The danger of encouraging a Northern writing considered as distinct is that it valorises stereotypes of the north that are themselves somewhat imprisoning and limiting. Neither of these novels do this but that is not because their primary purpose is ‘Writing the North’ but in precisely showing the narratives of the North vis-à-vis other spaces must be reappraised and rewritten from many perspectives simultaneously, not all them intrinsically Northern but finding their place (and the suppressed histories therein like Maurice Dobson’s). Nevertheless, that writing is in the end by necessity an admission that the North must be seen not in its most ‘positive image’ but as a fact in lives seeking refuge in that, and finding it but only together with patches of the threat it poses:

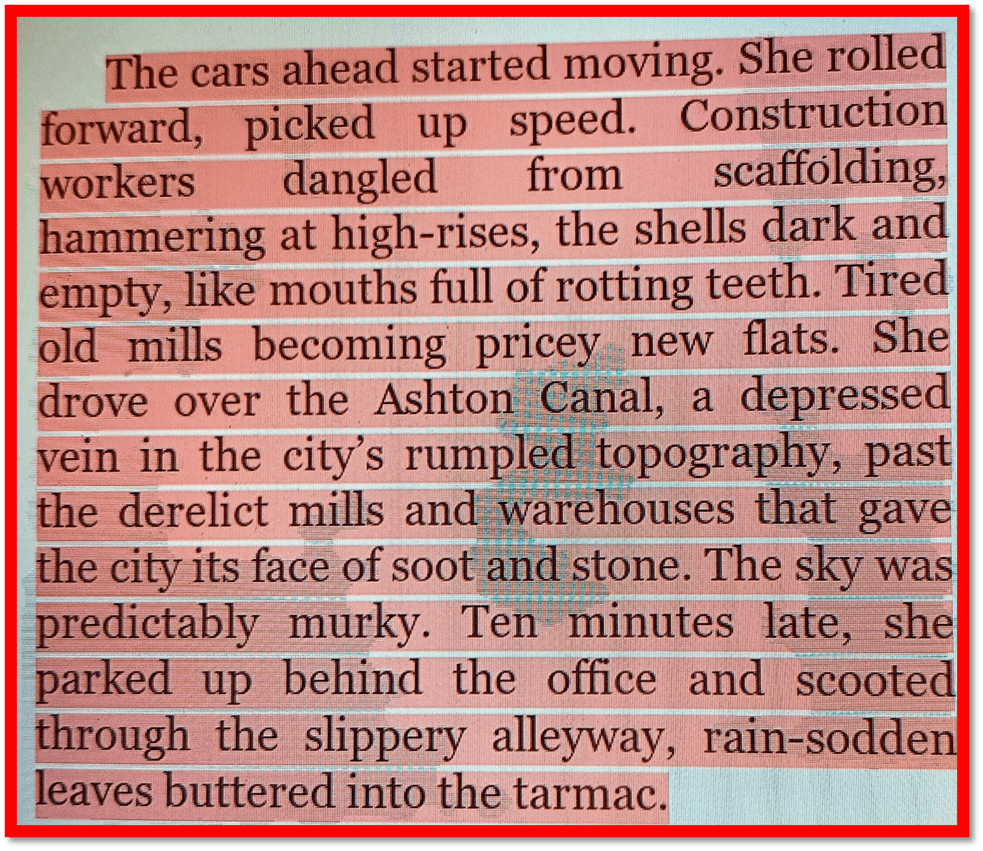

This passage is in Tawseef Khan, op.cit: 4 in the hard copy of the novel. The photograph from my Kindle highlighted passages.

This passage from the first two pages of the novels shows Ancoats as Jamila sees it on the way to her office – a space defined by the time span of history, including contemporary history, as well as the duration of a journey, and with the visceral quality of an body where desire and disgust might both be used in its appraisal. There is love here – in the leaves buttered into the tarmac but it is far from simple. Grief and nostalgias predicted in the ‘inherited trauma’ model invoked in McMillan’s novel? Perhaps, but also something that must be faced if we are ever to change it, and it will take more than concentrating solely on the North.

I will though definitely stop here because some things I am sure I will have got wrong and I respect (nay ‘love’ – for the art produce is worthy of love, wanted or not) the writers too much to continue when I feel this. Sometimes I ache for a community that would discuss these issues with me. So feel free to join me in such communion. If anyone is reading this. LOL.

From ‘Reading Sacred Texts Queerly’ available: https://slideplayer.com/slide/12206467/

But for now, I recommend both books, especially to queer readers and frankly if you are a true reader (even of the Bible as the above slide argues) you ought to be a queer reader – one who reads inside and outside norms set as freely as they breathe, refusing to ‘resist’ difference.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Tawseef Khan Determinations (2024: 192) London, Footnote Press.

[2] Ibid: 22ff.

[3] Ibid: 260

[4] Ibid 125

[5] Ibid: 141

[6] See Andrew McMillan Pity (2024: 122ff), Edinburgh, Canongate.

[7] See ibid: 190ff. For the poet see ibid: 94ff.

[8] Ibid: 166 (Puttana is the name of Simon’s usual drag-persona, a character from Jacobean comedy. See my blog: This is a blog on Andrew McMillan (2024) ‘Pity’ Edinburgh, Canongate Books. – Steve_Bamlett_blog (livesteven.com) at: https://livesteven.com/2024/02/14/this-is-a-blog-on-andrew-mcmillan-2024-pity-edinburgh-canongate-books/?_gl=1*ijm2va*_gcl_au*OTg1MjkwNDQxLjE3MjYwNDY4NDI.

[9] Tawseef Khan, op.cit: 232

[10] See in particular ‘Chapter 18: Zulfikar’, ibid: 188ff.

[11] ibid: 192.

[12] Ibid: 11

[13] Ibid: 188

[14] Andrew McMillan, op.cit: 110

[15] Ibid: 103

[16] In Memoriam (Tennyson) Canto 117 – Wikisource, the free online library Available At: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/In_Memoriam_(Tennyson)/Canto_117

[17] Andrew McMillan: 49

[18] Tawseef Khan, op.cit;131

[19] ibid :137

One thought on “Regions, towns, cities, identities and village people: Determining the nature of Community. This is a blog about seeing Andrew McMillan & Tawseef Khan.”