Anyone who attempts this question will soon get caught in a trap, for the first word of their answer will be their downfall: ‘I am most proud of …….’, they start and then describe a quality of their personality or appearance in the world, or perhaps some past action undertaken that they feel deserves notice, by them even if by no-one else. The problem is in in the first word ‘I’, the first person singular, who must state their claim to praise – the locus of their pride-in-self. But that first-person, in stepping into limelight,whilst it asserts its own value, isolates that value from what might make that value of some use to itself or others It turns itself into an object at best, a single simple word at worst, that isolates and renders static the very thing that ought to be in the company of those doing active good,alone or collaboratively and moving people or mountains as its justification in performance.

Lyric poetry is the best example of the fate of the observant static ‘I’ obsessed with its own witness of its own actiona, delberately independent of others from whom it has distinguished itself. One of the poems that comes to me at night when I can’t sleep, as in the late hours of last night is that known by its first line: ‘They Are All Gone Into A World of Light’.

This poem even sees the dead as more active than this sombre ‘I, hardly distinguished from the thing the word ‘I’ translates into, by virtue of a homophone alone: an ‘eye’. Henry Vaughan‘s gloomy seventeenth-century ‘I’ / ‘eye’ looks upon others, even dead others who at least have had the gumption to ‘go’, rewarded in the process with ‘light’ whilst his eye seeks meaning in the shadows.

Henry Vaughan

If ‘I alone sit ling’ring here’ (the second line of the poem) the only place my eye gets any clarity of vision is of them in the past wherein I saw more plainly. The pursuit of clarity of vision, where we ‘see clearly now’ haunts this poem, even down to the conceit in the last stanza where the ‘I’ laments the lack of perspective, from a hilltop, that confines it thence to the need of a ‘glass’. Vaughan means perhaps some telescopic magnifying glass that he is forced to use, although along with the word, perspective, it suggests also the instrument we sometimes call a ‘Claude glass’, a camera obscura that helped painters gain perspective. And the echo of that ‘glass’: ‘For now we see through a glass darkly; then face to face’ (Saint Paul in I Corinthians 13 verse 12). But for now, forget the Christian resonance and look at what this tells us about both the ‘I’ and the ‘eye’ of which we are so PROUD. They are less alive than the dead for they are the instruments used by the ‘living dead’, absorbed in ‘glimmerings and decays’ (glimmerings at the best …), people waiting to die.⁸

They are all gone into the world of light!

And I alone sit ling’ring here;

Their very memory is fair and bright,

And my sad thoughts doth clear.

It glows and glitters in my cloudy breast,

Like stars upon some gloomy grove,

Or those faint beams in which this hill is drest,

After the sun’s remove.

I see them walking in an air of glory,

Whose light doth trample on my days:

My days, which are at best but dull and hoary,

Mere glimmering and decays.

O holy Hope! and high Humility,

High as the heavens above!

These are your walks, and you have show’d them me

To kindle my cold love.

Dear, beauteous Death! the jewel of the just,

Shining nowhere, but in the dark;

What mysteries do lie beyond thy dust

Could man outlook that mark!

He that hath found some fledg’d bird’s nest, may know

At first sight, if the bird be flown;

But what fair well or grove he sings in now,

That is to him unknown.

And yet as angels in some brighter dreams

Call to the soul, when man doth sleep:

So some strange thoughts transcend our wonted themes

And into glory peep.

If a star were confin’d into a tomb,

Her captive flames must needs burn there;

But when the hand that lock’d her up, gives room,

She’ll shine through all the sphere.

O Father of eternal life, and all

Created glories under thee!

Resume thy spirit from this world of thrall

Into true liberty.

Either disperse these mists, which blot and fill

My perspective still as they pass,

Or else remove me hence unto that hill,

Where I shall need no glass.

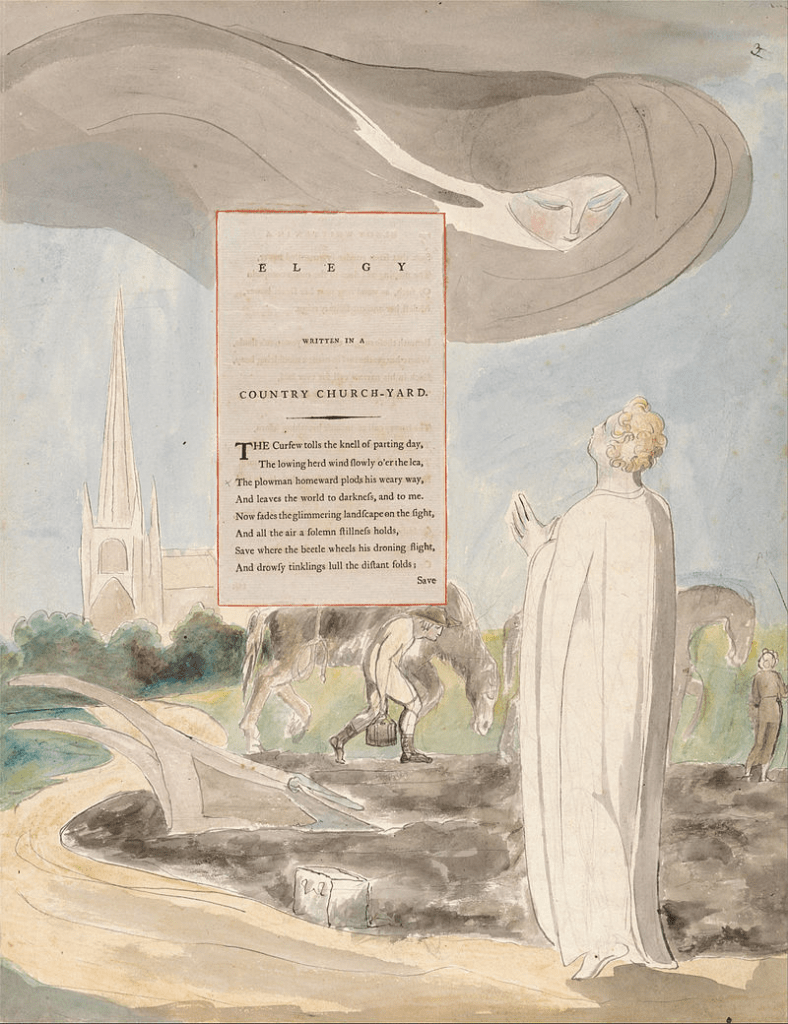

For the lyric ‘I / eye’ can only linger and watch these things of the world ‘pass’. Even passing (dying ultimately, but any act of passing by the watcher) is more full of life than the act of proud clinging onto one’s special instrument of vision – the thing of which you are so proud. The point is even clearer in a less theistic world than Vaughan’s seventeenth-century. Notice the elegiac lyric ‘I’ in Thomas Gray‘s Elegy Written in A Country Churchyard. Notice how it starts. The world is all passing by, but though that denotes its eventual passing in a series of deaths, it is considerably more lively, even the weariness of the ploughman looking forward to home, than the static eye left to darkness, that refuses top be moved as it comments upon vanity:

And that poem is also about the dark vanity of the entitled, those proud to call themselves ‘I’ and to praise their own refined witness of the world through the possession, like all their other proud possessions, of a ‘good eye’.

Nor you, ye Proud, impute to these the fault,

If Memory o'er their tomb no trophies raise,

Where through the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault

The pealing anthem swells the note of praise.

(lines 37-40, for text see https://thomasgray.org/cgi-bin/display.cgi?text=elcc)

And the secret of Gray’s Elegy is that that its poet is only ever an object (‘me’) equated with the ‘darkness’. The only time he becomes an ‘I’ is in saying how he misses a man he loves but to whom his love was never spoken (‘I missed him on the customed hill’). There is more of projected identification than clarity in the statement of Gray’s love as his imagination wreathes the ‘fantastic roots’ of its body round the last lover’s ‘listless length’, and wonders why he never even smiled at the young man he loved, leaving all smiling to be that imagined in him ‘as in scorn’, ‘crossed in hopeless love’. No wonder there is little ‘I’ in Gray’s poem. What after all is there to be proud of in never speaking for the good nor easing the other’s woe.

There at the foot of yonder nodding beech

'That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high,

'His listless length at noontide would he stretch,

'And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

'Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn,

'Muttering his wayward fancies he would rove,

'Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlorn,

'Or crazed with care, or crossed in hopeless love.

'One morn I missed him on the customed hill,

'Along the heath and near his favourite tree;

'Another came; nor yet beside the rill,

'Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he;

(lines 101-112, ibid.)

Gray was undoubtedly a queer man, friend of the more flamboyant Walpole, but rather less able like Walpole to cast his signature over the built world in fanciful Strawberry Hills. But Gray had a kind of inverse pride too – in being the poet of a respectable passivity before the vanities of the world. When William Blake illustrated the poem’s first stanza, he seemed to show Gray as potentially a man of light, with empathy for the labouring ploughman (the kind of empathy that for Blake fed socialism) but about to be smothered by ‘darkness’ in the form of a dark cloud. The cloud is, even as it descends, transposing itself into an avid nun about to suck out his life like a succubus, often the role of the established Church in Blake’s eyes. I think Blake got Gray right. Better make home with the ploughman and leave the pride of your own reserved saintliness as gentleman-poet, clothed in white robes: that is, at least, if you haven’t the gumption to ease the woe of your chosen love with your love embodied than get absorbed into the lonely pride of stillness that looks like religion. Being absorbed in the pride of dong nothing but stand there looking as if you were respectable gets us nowhere.

These musings go nowhere either. Were they ever meant to?

With love

Steven xxxxxxxz