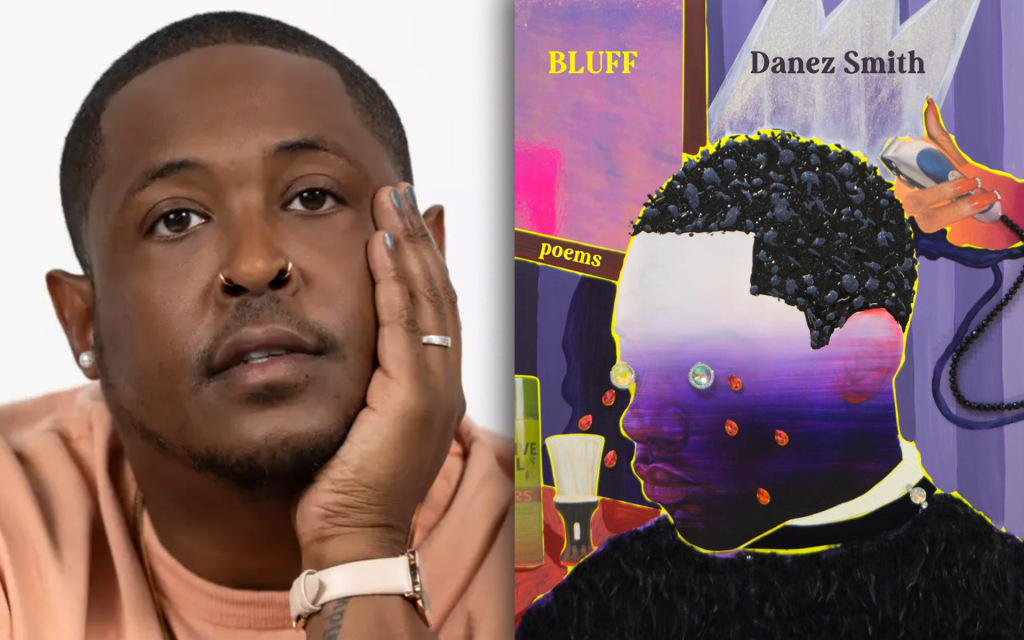

‘how dare I love you here in the evidence of evil’: some thoughts about Sioux Falls in Danez Smith (2024: page 81) Bluff London, Chatto & Windus.

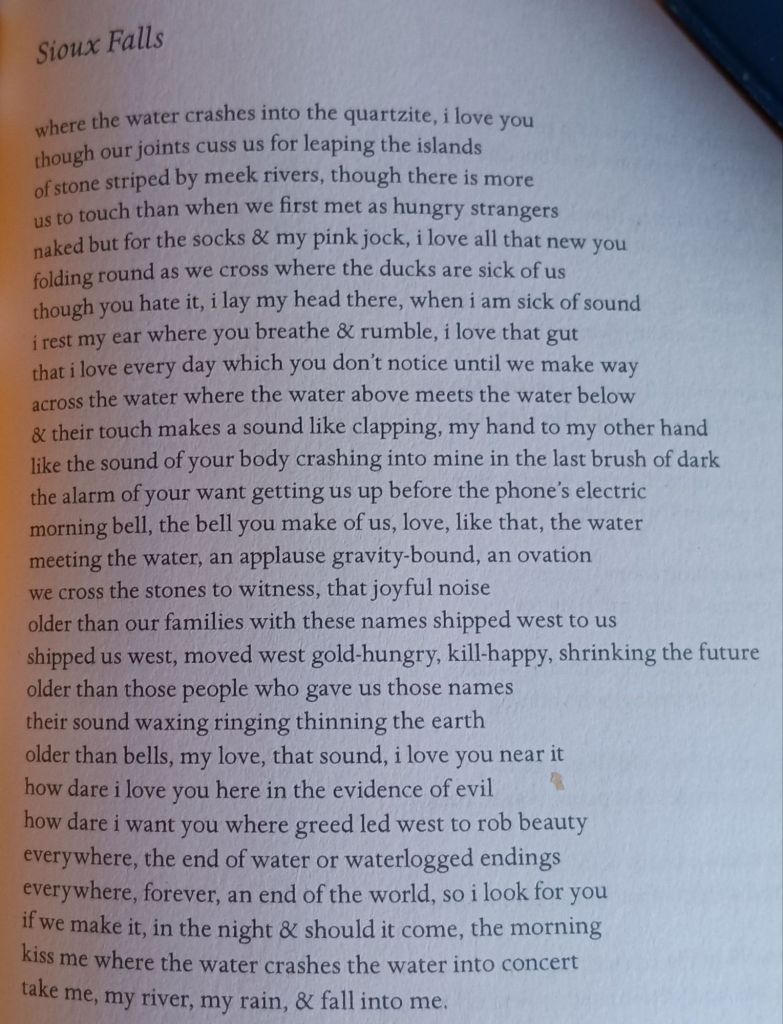

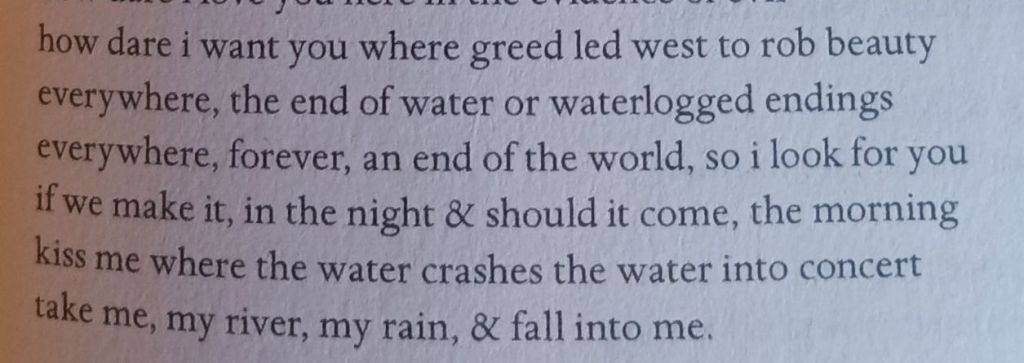

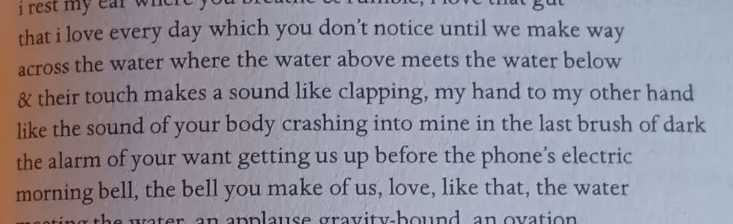

This blog is a preliminary in a mini-project to prepare myself to hear Danez Smith reading from Bluff at the London Literary Festival at The Southbank Centre at 3.15 on October 26th 2024 as part of my birthday present from husband Geoff. I am reading through Bluff and returning back again to poems as each shows its impact on me in various ways, in the aftershocks of first reading. When I reached a poem named Sioux Falls (page 81 of the beautiful volume) I stopped entirely and until I try to come to terms with its beauty, freshness and power I can’t move on. So here I try to write out a little of why I think, at the moment, this poem impacted upon me. Here is a photograph of the page.Hear Danez reading the poem at: https://soundcloud.com/the-adroit-journal/danez-smith-sioux-falls#:~:text=Stream%20Danez%20Smith%20-%20Sioux%20Falls%20by%20The%20Adroit%20Journal

The impact of Sioux Falls is surely in part that it queries whether it is possible or ethical to profess love in the presence of ‘evidence of evil’ (a point that astounds me as I watch the British government condone the Palestinian genocide it watched happen). That ‘evidence of evil’ is everywhere in the marks history leaves in the present – in its international and national politics, landscapes, communities, relationships, persons , and in various scarred things within them like bluffs, marked skin, viscera and perhaps even marked souls. I have though never seen it tackled in ways that take on too the interpersonal histories of how personal comfort too gives notice of the love of the long-loved one’s body as it rests necessarily into the landscape of evil, there being no alternative landscapes on offer. In Sioux Falls the lyricist notes that their lover is acquiring ‘more to touch’ in their body, folds of ‘new you’ (and me) and a comfortable gut and viscera singing as they must involuntarily whilst they ‘breathe and rumble’ – the lovers by the present time of the poem are no longer meeting as ‘hungry strangers’ nor as thin strangers.

Hungry strangers may feel the pulse of desire more strongly and more cleanly perhaps – where flesh does not ‘crash’ together and flow and ‘fall’ into the other with the beauty and slight but loved discomfort of ‘rain’. And perhaps our ‘joints cuss us’ now on exertion – whether these be the aging joints no longer agile in jumping between stones on the Sioux river or the joins of our relationship too ready to cuss sometimes rather than rejoice. But if ageing together means acquiring flesh in the ‘new you’ it also means a kind of moral growth too where it is clearly much more important to query how to dare to say that you love another in this ethically filthy world than to know you didn’t even care ONCE to dare when ‘hungry’ and slim to be ‘naked but for the socks and my pink jock’.

dare when ‘hungry’ and slim to be ‘naked but for the socks and my pink jock’.

Sioux Falls is a real place. Though the photograph above shows some of the rocks bold guys might choose to jump between and ‘cuss their joints’ after and contextualize the metaphor of the sound and mighty feel of water falling and crashing from one body of itself to another, its reality likes in the modern city the Sioux Falls Park can’t hide – dense in its brutal concretion.

But real places have real histories though a glance at the City website shows that even now that history is sanitised with its rather soft treatment of the genocide the place’s history hides, though showing enough of the ‘evidence of evil’. For Smith that evidence is compact with intersected stories of inter-racial brutality that, in the image of the drive West by white formerly European settlers, in this area fired to boiling point by the discovery of gold on land thought to be reserved for displaced Native American populations, also includes the shipping of slaves for the gain of gold in another less direct means – that of exchange of goods, into which African-origin bodies and energies had been transformed and named after their White owners like the ubiquitous Smiths.

older than our families with these names shipped west to us

shipped us west, moved est gold-hungry, kill-happy, shrinking the future

their sound waxing ringing thinning the earth

How forceful are those lines as ‘meek rivers’ in falls such as these turn into a place where ‘the water crashes into the quartzite’.The hardness of quartzite is the result of ancient elemental histories that no present current of however ‘meek’ a river can resist but fall over, and crash. It is a wonderful metaphor – learned from Whitman’s use of ancient geological landscapes, but so much more politically awake – of how a history of the evil, the story of numerous falls from grace (not one fall as in Judaeo-Christian mythology), fragments any sense of what we call the ‘pure’ pursuit of abstracts like love – but also beauty and poetry.

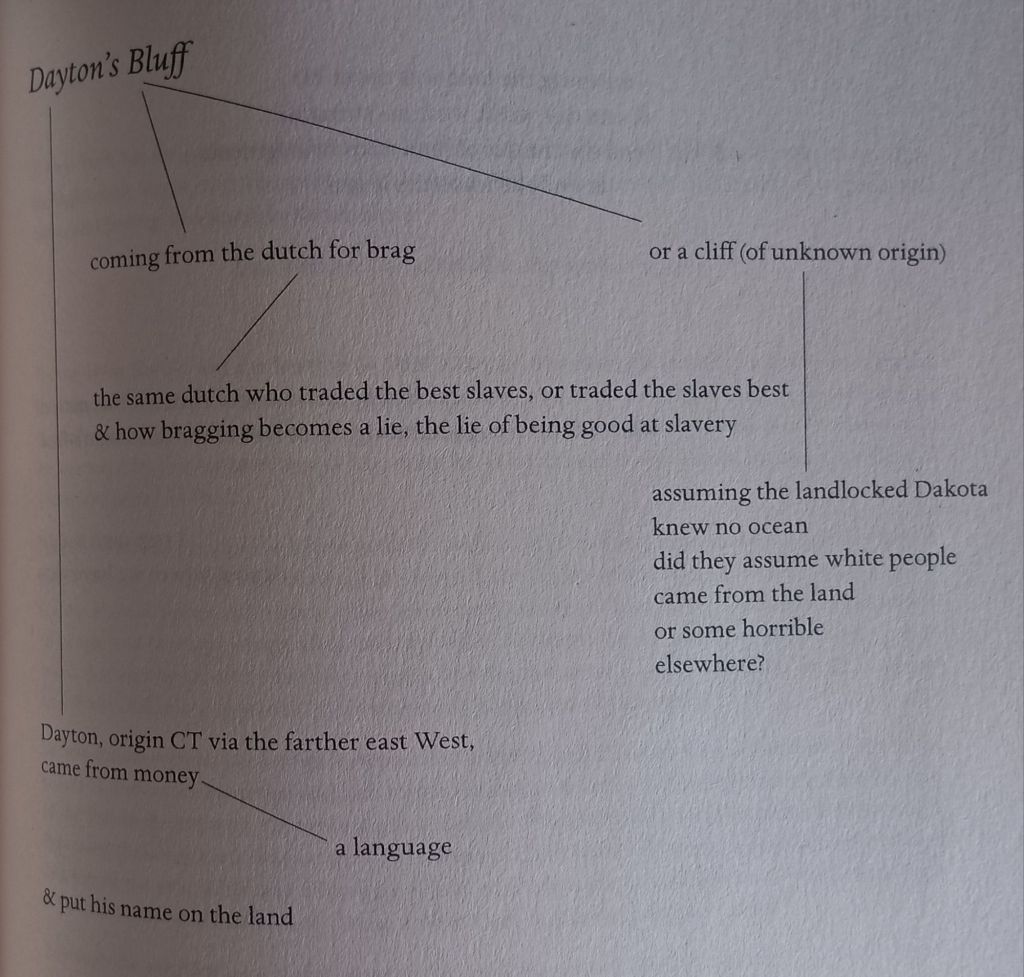

For this is the contention of the whole book, that I want to blog about later, that poetry itself – with its assumed hot line to beauty, truth, love and all the rest could be a ruse by a fallen world (betrothed as ever to capitalist imperialism, a bluff like those scars or ‘bluffs’ in the landscape, like Drayton’s Bluff in the poem of that name: another stolen and disappeared Indian metropolis based on a decisive landscape formation now colonised by white brutality that pretends (or bluffs) that it is otherwise:

Drayton’s Bluff (page 33) is one of the innovative poems I want to investigate later. Can such works only be poems that demand a reader perceiving their given and prescribed spacing and placement by the poet, for instance, or do the freer sound values of orality still predominate? The latter is thought – perhaps wrongly – to be the convention. But is it?

These are questions to ponder later. Meanwhile I remain bowled over by Sioux Falls and must think why that might be. Like Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach, this poem shifts between reflexive observations on a place in space and a relationship with the supposed addressee of the poem, which whom the lyricist is in love. Like that poem too it has an apocalyptic edge. Here’s Arnold:

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Arnold’s pictures a world of fragmentation and division in other voices are merely those consituting ‘confused alarms’ sounding out from ‘ignorant armies’ on a ‘darkling plain’. The echoes even in that poetic characterisation seem to be from a classical tradition at least as old as Classical Greece in which Arnold has an established and entitled place as the spokesman of white male western tradition. Arnold’s immediate predecessors and mentors such as Wordsworth and Shelley parsed that tradition to embody a model of the Romantic poet as sage interpreter of the laws that defined the ‘Good, True and Beautiful’. In Smith, the lyricist does not speak of others as ‘ignorant’ not least because they do not see the fact of being a poet as giving access to even a notional social privilege like that claimed by Shelley for the poet as ‘unacknowledged legislator of the world‘.

Smith’s lyricist is tentative, not even claiming the distinction of an upper-case ‘I’ , and interpreting the Western tradition (that which ‘led west’) as an end to what flows free, like the Sioux river above the falls, and must be end-stopped by obstructions to form ‘the end of water or waterlogged endings / everywhere, forever , an end of the world’. The worlds that white imperialism ended where like those of branded slaves shipped west, like the Sioux nation enclosed in a reservation, the ultimate genocidal tactic on a nomadic people, to subject them to mass starvation and Western diseases and capital-fuelled alcohol production from which they had no protection. Whereas Arnold seeks for his love, as a feeling and its object, to mask the lack of ‘certitude’, ‘peace’ and ‘help for pain’, Smith poses his trust in their lover and the hope of a ‘morning / kiss’ on a conditional – ”if we make it, in the night & should it come, the morning’. Their ‘concert’ of disturbed sound, its ‘crashes’ (like Arnold’s clashes’) being in the certainty that in fluidity and even round rocky obstruction, both being ‘taken’ and penetrated within by another flow such as his own with not dispossess but repossess him of a birthright ‘my river, rain, fall’, which might be that of the Sioux or of others wherein ‘greed led west to rob beauty’.

That Smith can only ‘dare’ this rather than assert his right as Arnold does, despite the obstacles of what elsewhere he called ‘Philistinism’, to what is the ‘ land of dreams, / So various, so beautiful, so new’ that poetry conjures knows all dreams are tainted appropriations of the dreams of others. Dover Beach as a place in space is an entirely validated boundary of English topography and culture, a limit of what it means to speak and talk in English as Arnold sees it, having few Transatlantic yearnings as Dickens and Oscar Wilde had. Sioux Falls attests to a genocide completed, not only of a people by its varied cultures; though its survivors, like Tommy Orange (see my blog at this link) look to find a new form of creativity in compensation and a respectful appropriation and sharing of Black, queer and Native American marginalised histories and topographies. One can only ;’dare’ to hope that such appropriations are not as insulting as those of the White West of other subordinated cultures, for the aim is NOT in Smith to subordinate. If his wonderful poem ends with a ‘concert’, a performative togetherness, it resounds throughout with clapping where performer and audience, self and its others become one in mutual admiring praise (being clapped as in a theatre) and intermingling of ‘flow’ between waters and the fluid bodies water represents.

I love it that the alarm clock (‘electric / morning bell’) metaphor recalls Arnold’ ‘confused alarms of struggle and of fight’; though I cannot even suppose as a long shot that Danez Smith intended that echo. Nevertheless, the point is I think for me that Smith is continually wanting to differentiate the fact of human desire from its deformations in capitalism, and that is surely the point of the line that still rings in my ears (I italicise and bold the words of significant comparison):

how dare I want you where greed led west to rob beauty everywhere, forever, ....

There is a desire that is not greed, nor that leads to robbery or appropriation. And that is why we still need poetry, provided we can tell the false from the true (and really be ‘true to one another’, Matthew Arnold), the true hand from the bluff one.

I feel I can read on now. Can’t wait till October 26th but will be back before then with more on Bluff.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

6 thoughts on “‘how dare I love you here in the evidence of evil’: some thoughts about ‘Sioux Falls’ in Danez Smith (2024) ‘Bluff’.”