‘[The moon rises at back, mounts in the sky, stands still, shedding a pale light on the scene.] …. ESTRAGON: “Pale for weariness” VLADIMIR: “Eh?” ESTRAGON: Of climbing heaven and gazing on the likes of us.” A blog about feeling not worthy of ‘its constancy’, and a case for a ‘queer’ reading of a classic play, in Samuel Beckett (2000, first published 1956) Waiting for Godot: A tragicomedy in two Acts London, Faber & Faber [1]. Preparation for seeing the production at the Haymarket Theatre, London 7.30 pm. on 25th October 2024.

Time will be on my mind when I travel by train to London on the 25th October because this trip is for my 70th birthday. There will be other blogs on the trip for the day starts once in London at the National Gallery blockbuster Van Gogh exhibition before I drop my things in a hotel near Elephant and Castle and return in the evening to the Theatre Royal Haymarket, which Michael Billington in predicting the pitfalls that any new production of a play with its honourable stage history calls ‘that temple of luxurious elegance’.

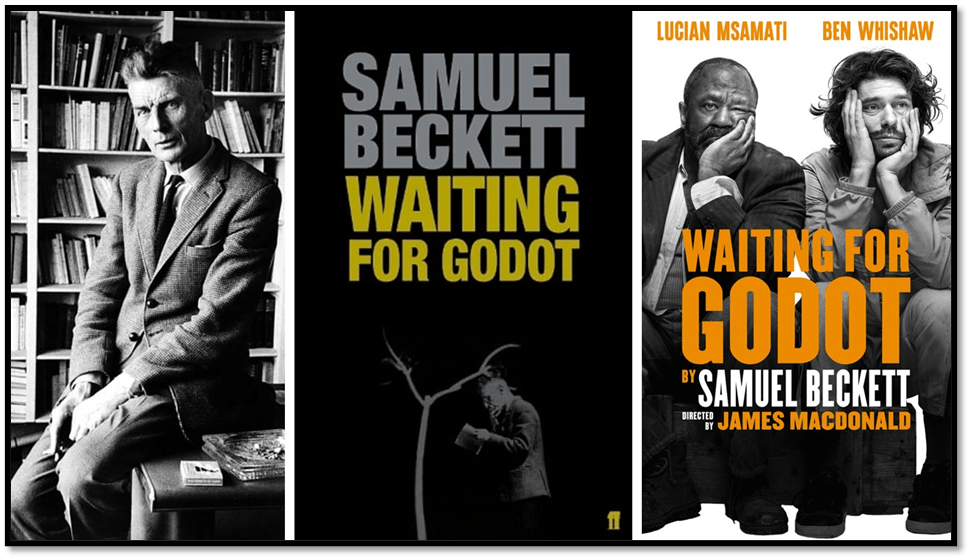

Billington’s article must have gone down strangely with the play’s director this time, James Macdonald and the stars who play plat Didi (Vladimir in full) and Gogo (Estragon), Ben Whishaw and Lucian Masmati respectively. That is so because the article seems to play upon one particular warning to the director and actor that they do not assume that ‘the way we stage Waiting for Godot’ should also be ‘changed with time’, and in one particular at least:

The difficulty Godot poses is that it is both tragic and comic but too much emphasis on the latter element can unbalance the play. … (A) West End production in 1991, starring Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson, which by milking every line for a potential laugh sacrificed Beckett’s sense of desolation. …

I still await the new Haymarket revival with eagerness. The test for me will be whether it acknowledges the play’s comedy without lapsing into self-regarding sentimentality and whether it captures, as Beckett’s own production did, the derelict dignity of the two tramps and the human capacity for endurance in a seemingly senseless universe. [2]

For an old man of the theatre to issue such warnings may mean he had his ear to the ground about this production, for though universally credited with being true to the text, Alexander O’Loughlin in The Tatler of all places says:

This adaptation revels in the play’s humour, offering a fresh and engaging interpretation that contrasts the existential heaviness often associated with Godot. ….

Macdonald’s focus on the comedic elements was a refreshing shift, with Whishaw and Msamati honing in on the vaudevillian qualities of their characters. Along with Jonathan Slinger and Tom Edden’s performances as Pozzo and Lucky, the cast’s timing and physicality are impeccable, offering a feeling of delight amidst the original bleakness of the play’s existential themes. While traditionally Godot tends to emphasise a sense of despair, this version invites the audience to laugh at the absurdity of the human condition through the games they play, the stories they tell and the notable three-minute hat swapping sequence. Perfection .[3]

This does not sound very much like Michael Billington’s advice followed as strictly as it might be, though clearly it is to O’Loughlin’s taste. This may not be because the play denies that that which we find comedic is not also tragic, but it certainly stands against the notion of an emphasis on ‘derelict dignity’. Billington was no longer the drama critic at The Guardian when he wrote that article but one of his successors, Arifa Akbar, who seemed to have read and agreed with Billington and have found the problem he predicted to be edgily there:

Samuel Beckett’s 1953 tragicomedy about two woe-begotten men waiting by a willow tree for a mysterious figure to appear tips a delicate balance between the absurd and desolate, the funny and dreadful.

In James Macdonald’s production, the drama between Estragon (Lucian Msamati) and Vladimir (Ben Whishaw), who are yoked together in unspoken bondage as they wait for Godot, seems greater parts comedy than tragedy.

If at this point we wonder if we are heading for a condemnation based on Billington’s suspicion of the spurious modernity principle in the mounting of plays, we can have no doubt of that when Akbar speaks of the second act:

It gets more overtly clownish in the second act, with more physical comedy and even a Laurel and Hardy-style hat-swapping routine. Between them, Vladimir and Estragon begin to look like hobos impersonating a musical hall duo. But the comedy brings flabbiness, too, the pace slackening, with not enough prickling tension between them[4]

Even the idea of ‘impersonating a musical duo’ seems to echo Billington for he critiqued Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart for doing just that in 2009, if with some sartorial elegance.

But outside the world of The Guardian, and possibly Billington’s ghostly influence from his retirement, most critics have rejoiced in the production decision to emphasise the comedic and to look for the tragic nuance in that. That is what I hope will prove the case when I see the play, for certainly nothing in my re-reading of it excludes such an option. When we read Sarah Compton, the reviewer for What’s On Stage, we sense the same play seen by Akbar, but seen with much more of an ear for the emotive and tragic nuance of even high comedy. Perhaps too with a more humanly-informed intelligence. I hope so. She says of the main character actors:

With exquisite timing, they find new ways through familiar lines – Whishaw’s little pauses, Msamati’s ironic flatness – making the language poetic and musical, but always naturalistic.

It’s a remarkable piece of tightrope walking and it lets them illuminate the richness of thought that runs through the play, subject of a thousand theses, but feeling new minted. They also constantly convey, by little touches and glances, the affection and closeness of the two men. …. /…/

When the couple reappear in the second act, with Pozzo now blind and Lucky dumb, McDonald plays up the physical comedy of the quartet’s collapse on stage, turning their movements into a kind of dance of chaos, the events and their words passing the time, staving off despair. [4]

Now this sounds like a theatre-goer unblinkered by expectations of what despair feels and looks like, for I think it rarely wears the mask of ‘derelict dignity’ when it is believable in life, as it does in the conventions of theatrical history. Crompton certainly understands the play and the ways in which time and contemporaneity get reflected, sometimes by deflection. She for instance, speaks of how the ‘misery conjured in his play, the violence that it shows, the hunger and the waste, were all things he had experienced’, detailing evidence from Beckett’s life with the French Resistance Movement, and their coverage in essays in the programme. And it is not just the bleakness of War time France but of the bleakness of the cyclical hopelessness of post-war years of economic depression where the agency of time seems toxic. And the production clearly goes for nuance here not binary balance:

The passage of time is one of Beckett’s main preoccupations in this purgatory where nothing is remembered and nothing remains and Bruno Poet’s lighting marks the descent from day to night in cool tones, a rich red changing the landscape only when the Boy arrives to announce the non-arrival of Godot.[5]

That is a neat passage in a theatrical review. It alerts me that just as the theatre must indicate through the use of its own devices, of which the variations of stage lighting effects are the main perhaps, the ‘passage of time’ so must strain to represent the experience of time not of a passage of its quantifiable measurement but of as an idea, emotion, and perhaps even of a sensation of things like heavy eyes, the pinch of clothing and a weary body. I do not know yet if, or how exactly, this production might facilitate tha awareness, and though here I summarise some reviews, my main source of interest will be expectations set up in me by rereading the text of Beckett’s play, which surprised me by its richness.

I have not read it since I did so in a Special Level (S-level as it was called) English course at grammar school in the 1960s, when the play seemed contemporary and to be liked for the modish intellectual edge it gave you when you said you were studying it or going to a Manchester theatre in order to see it enacted. Fiona Mountford in the i newspaper must have had a parallel if different experience. She speaks of seeing it at school but feeling ‘alienated and bewildered’ by it, ‘only realising later that Beckett goes down considerably better with those whom life has buffeted about a bit’.[6]

I fully agree with that last statement, although peculiarly what she predicts I will see does not match my expectations of the text, when she says that the characters Pozzo and Lucky illustrate ‘the ravages of time whereas Masmati and Whishaw are suspended in an eternal present tense of equivocation and uncertainty, …’. I think binary contrasts like these rarely predict real experience, even of plays, and in reading the text, I think there is much in the relationship of Estragon and Vladimir that speaks of time passing, even if sometimes in denial or, for Estragon, a kind of aesthetic sublimation. It is that I want to explore for myself in the text as preparation for seeing my play. Such preparation enhances my joy in a play. Nick Curtis in The Standard gives me hope, for he says:

I’ve seen many fine duos play the leads but this time I enjoyed and understood the play on a whole new level. …. / ….

Here the look, if not the words, are updated. Vladimir (Whishaw) and Estragon (Msamati) are not picturesque stage tramps but recognisably homeless men in shabby anorak and overalls, suffering the privations and ailments that rough sleeping leads to. / ….

… in Macdonald’s production it feels like human existence is distilled, albeit from the exclusively male perspective of the Forties and Fifties. Still difficult, still challenging, Godot isn’t for everyone. But this is the best production I’ve ever seen.[7]

This is respectful of both the play and the craft of theatre in all its domains, which Billington was not at times. If we are to critique the effect of our own times on the reproduction of classic plays perhaps we should do it like O’Loughlin, whom I mentioned previously, he of The Tatler. For he wanted more not less contemporaneity, of which he finds little in this production except in production style and the modernity of the blend of the plays language of its own period and the modern rendering of their inner life can now be understood.

Yet, for all its visual splendour and outstanding performances, one might still ask; what new ground does this production cover? …. / …/ For instance, when Godot was staged in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans in 2007, the play’s absurdity and themes of waiting were transformed into a potent metaphor for the socio-economic disparities and injustices of urban America. The play became a reflection of the marginalised communities still waiting for justice, survival, and recognition. This contextual shift gave Godot a new layer of relevance, a feat that is difficult to achieve in every staging of the play.[8]

I feel I have looked at the worst that could happen when I see these plays and found evidence for hoping for the best, or even better. One can only respond as one must in the theatre and I will do on in a future blog. But reading the play opened it up to me in ways it never was in my past. Though I revered it of course, reverence is never the recipe for keeping play’s alive. I have to admit tha I will prick to my ears to see how Ben Whishaw, my favourite queer actor, when as he enacts Vladimir waiting for ‘the last moment’, that Estragon accuses him of always doing, with all the richness given to that phrase, says the line: ‘Sometimes I feel it coming all the same. Then I go all queer’.[9] Again when he says in Act Two to Gogo about his night away from him: ‘I missed you … and at the same time I was happy. Isn’t that a queer thing?’[10]

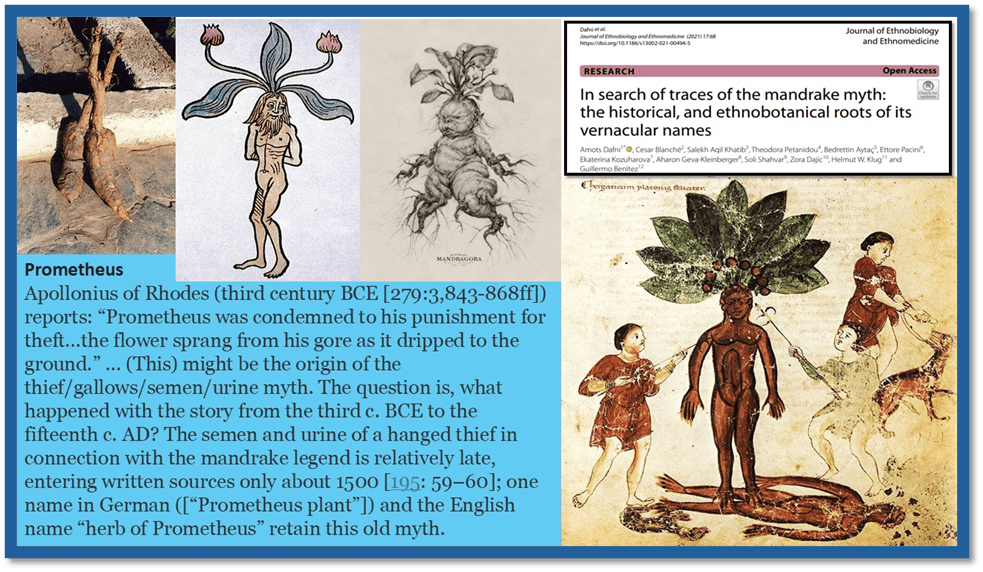

Absurdity and diversion from sexual and other social norms are more at issue in the play than I had ever imagined and I do not rely on a modern use of the word ‘queer’ in pointing this out. And indeed the term ‘queer’ was used, both pejoratively and otherwise even in 1950s. Recently, and I intend to read this book more fully soon, I became aware of work that demonstrates by applying ‘feminist, queer, and trans theory’ to Beckett’s rather offset interest in relationships in his novels and drama that stress the mutually embodied to ‘show the writer’s relevance to contemporary debates in the fields of gender and sexuality’. This book is Daniela Castelli’s Insufferable: Beckett, Gender and Sexuality in the Cambridge University Press ‘Elements in Beckett Studies’ series. The example Castelli uses from Waiting for Godot in setting out her stall of instances of what I call ‘Beckett’s rather offset interest in relationships in his novels and drama that stress the mutually embodied’ is the incident in which the central characters contemplate the advantages and disadvantages of a mutual hanging from the tree in their otherwise desolate landscape. Castelli writes:

We might be tempted to think that Didi and Gogo are just making a sill joke about the potential embarrassment of having an erection when hanging themselves despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that the Lord Chamberlain thought otherwise; he requested the line to be excised from the English production of 1954. [11]

I don’t quite understand why Castelli calls the two men’s reaction one of ‘potential embarrassment’. In fact the text shows an overwhelming interest in the event of a erection in what is a mutual hanging, if they can manage that – which has its own difficulties. It is proposed and received between them as a rather exciting prospect – emphasised even by Beckett’s stage direction:

ESTRAGON: What about hanging ourselves?

VLADIMIR: Hmm. It’d give us an erection!

ESTRAGON: [Highly excited] An erection!

VLADIMIR: With all that follows. Where it falls, mandrakes grow. That’s why they shriek when you pull them up. Did you not know that?

ESTRAGON: Let’s hang ourselves immediately[12]

It is not only that that Estragon gets ‘highly excited’ at the prospect of an erection that matters here but that the ‘erection’ is a mutual incident that connects their bodies. The excitement is in the joint hanging and the joint hanging, even, as they are to find as they discuss the options they have to hang themselves in serial order of some kind, but who gets to go first, potentially leaving the other alone? Far from embarrassed, the men can be conceived and enacted as highly energised by this act of what they think, but for a moment to be a site of mutual satisfaction and even generation through Didi’s invocation of the mandragora / mandrake myths that some see deriving from the idea of Prometheus’s challenge to Zeus that he is a better friend to humankind. The two men become highly mythical biological fathers, even if a dangerous and monstrous thing compounded in error.

Reading the play again, aware of course that the role of Didi will be played By Ben Whishaw, but not necessarily with any of these readings in mind or potential (we shall have to see) I became much more aware of the affective and physical (the latter operating under severe restraint) bonds between Didi and Gogo. In a kind of reverie Gogo speaks of his dreams of visiting the ‘Dead Sea’ which he conceives of as ‘pale blue’ as it is on maps, for ‘our honeymoon’. Whose honeymoon does he mean? The time could well predate Didi’s appearance in his life, but we can’t deny that the tendency to first person plurals in this play seems always to encourage a sense of desired unity, as in the phrase ‘hanging ourselves’ in the being of both men, desired but resisted. It seems to motivate moments of commitment and tenderness, sometimes withdrawn in embarrassment as when Estragon imagines that he’ll ‘never walk again’ as a result of the kick Lucky gives him and Vladimir says: ‘[Tenderly] I’ll carry you so. [Pause] If necessary’.[13] Surely an actor here veers between tenderness as called for and a resumption of the masculine feeling that touch or proximity between male bodies may only be in practical ‘necessity’ not from desire or feeling of any kind.

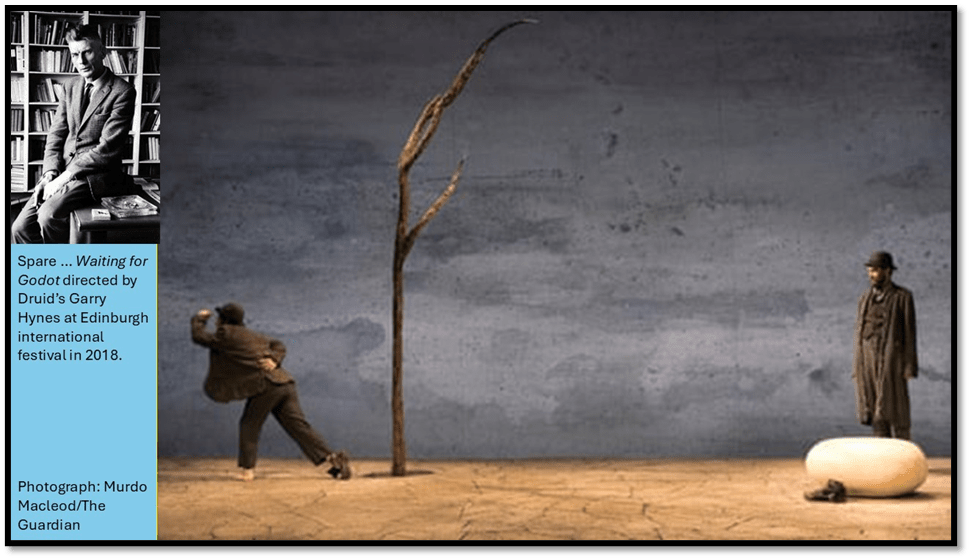

Just before the end of Act One, the guys discuss how they first met and where Didi seems to have ‘fished out’ Gogo, perhaps from a watery death, fifty years ago ‘perhaps’ says Didi. They continue to discuss the chances of their relationship and common goal (in the metaphor of a road) having continuation. Estragon wonders ‘if we wouldn’t have been better off alone, each one for himself’, for they ‘weren’t meant for the same road’.[14] Arifa Akbar points out that though the set by Rae Smith is ‘post-apocalyptic’ in resonance, with mounds like those in later Beckett plays that, in those plays but not this one bury their protagonists up to the neck, in this new production, there is no sign of its site of a ‘country road’ as specified by Beckett: ‘’A country road. A tree. Evening’.[15] O’Loughlin thinks this production’s ‘barren, dreamlike space perfectly mirrors the existential void of the piece’.[16]

Even in the 2018 production by David Gary Hynes picked out by Michael Billington as the best so far had no obvious indication of a road on set.

Nevertheless the ways of enacting common purpose and direction extend beyond metaphors of a visible road, along which neither go, at least in sight of the audience, although they gaze at what may lie beyond it, before the curtain falls. In Act Two, apparently the next day, they are reassembled at the same place on the same road still querying each other’s state of feeling about their union.

VLADIMIR: You must be happy, too, deep down, if you only knew it. ESTRAGON: Happy about what? VLADIMIR: To be back with me again! ESTRAGON: Would you say so? VLADIMIR: Say you are, even if it’s not true … We are happy [Silence] ESTRAGON: What do we do now, now that we are happy?[17]

Yet despite the fact that my reading of this restrained emotion for each other in Didi and Gogo, critics have given no support for such readings in the past and even now, so I cannot know if it is there to see in this production where an actor of Whishaw’s intelligence about the shades with which queer relationships manifest themselves would have seen in the text. I can but see. Certainly Akbar’s characterisation of her interpretation of what the production shows, as of two men ‘yoked together in unspoken bondage’ rather minimises any sense of affect as a phrase to open her review, she goes on to say nevertheless two paragraphs on that there is an enactment of ‘affection between them that is endearing – they gravitate towards each other and hold hands boyishly’.[18] Nevertheless, all that seems to confirm that the emotion tends to the wistful rather than the tragic, which she believes to be required.

Surprisingly, given the way I have favoured O’Loughlin’s reading of the play as he saw it, his description of the central male relationship undermines giving it credence as a relationship mediated by desire and resistance to desire even more than Akbar. He says of his interpretation of how the men enact the relationship that ‘their chemistry was perfect, at times romantic in a platonic sense – a codependent friendship based on a hatred for being alone’.[19] I don’t see how we get to the idea of the Platonic here, which is a concept indicating the active renunciation of a sexual element in a relationship, to which Alcibiades, the drunken but beautiful young Athenian statesman, attributes his inability to seduce Socrates in Plato’s The Symposium. The relationship may be ‘codependent’ but it does not lack the characteristics of many other relationships, ancient and modern (even ones I have experienced myself) and certainly does not mean the basis of the relationship is related only to a mutual selfish fear of isolation. I sense that more in Sartre’s Huis Clos, but Sartre was not the artist that Becket was.

My interest in the play may be to interrogate a little more and with less certainty that I know the intentions of Beckett than the critics I’ve cited what the closeness that that the actors in this production have given to Didi and Gogo. I think alertness to the importance of ‘touch’ and ‘touching’ in the play is required here, and a richer sense of how to interpret how and why we touch each other.

The classic means of understanding Didi and Gogo must hover around the many references to an ‘embrace’ desired and given (or denied) in the play and how we read these issues of proximity and distance – some critics refuse to read them at all, which is itself heteronormativity that runs deep in supposedly critical souls. Vladimir demands an ‘embrace’ from the start as emblem that they are ‘Together again at last’, but is rebuffed by Gogo, at least for now, perhaps because his experience of separations is so much more viscerally violent, represented as being beaten by many offensive men while he lies in a ditch: [Irritably] Not now, not now’. [20] When the first embrace does happen, they find reasons for ending it with relative distance. Vladimir ‘stiffens’ before he ‘softens’ at Estragon’s touch, and Estragon uses the fact that the other stinks ‘of garlic to ‘recoil’ from him.[21] What follows is the episode on the proposed mutual erection on mutual hanging.

In Act Two, the first embrace of the evening is horribly complicated by feelings of desire, past rejection and defensiveness:

VLADIMIR :… Come here till I embrace you.

ESTRAGON: Don’t touch me. [Vladimir holds back, pained.]

VLADIMIR: Do you want me to go away? [Pause] Gogo! … Where did you spend the night!

ESTRAGON: Don’t touch me! Don’t question me! Don’t speak to me! Stay with me!

VLADIMIR: Did I ever leave you?

ESTRAGON: You let me go.

VLADIMIR: Look at me. [Estragon does not raise his head. Violently.] Look at me!

ESTRAGON raises his head. They look long at each other, then suddenly embrace, clapping each other the back. End of the embrace. ESTRAGON no longer supported, almost falls.[22]

Enacting this exchange, involves being able to give TOUCH meaning in the manner we speak it, embody it and move with it. That Gogo, ‘no longer supported, almost falls’, feels to me both comic and tragic – not because, in Billington’s terms, the actor seeks a spurious balance, but because standing and falling are themselves poses of deep affect as well as visual humour (and there will be much of it in Act Two). I hope to comment on this after seeing the performance. The next time the two embrace, as instructed in a stage direction, is immediately before a plethora of clown-like displays of attempts to support that fail so that all fall, at first in the failure of the two men to live up to the rhetoric of words like ‘Come to my arms!’, such that they fall silent with each other and just ‘wait’ again, and then projected into Pozzo and Lucky (now, in Act Two, respectively blind and mute).

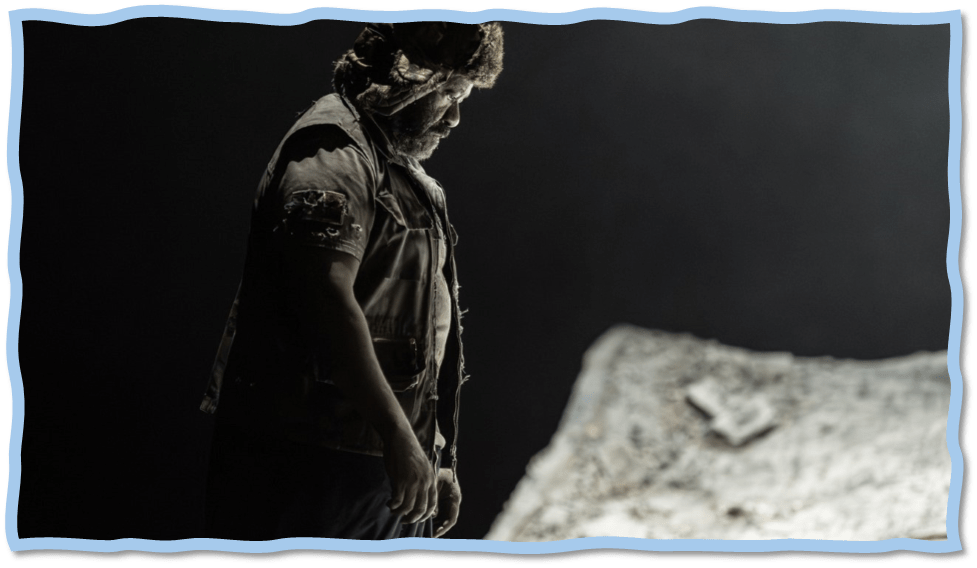

Pozzo and Lucky by the way are I think perfectly there to simulate symbolic forms of relationship that differ from those of Didi and Gogo as much as they bear symbolic commonalities – as in their falling in Act Two. In Act One their relationship is formal – that between master and slave, a model that is potential to Vladimir and Estragon but continually resisted by the advent of emotion in my reading. Full of symbols of connection and reasons for it – like inequality of power and status, the realisation of bonds as a rope bond, almost like a noose that the two insist ensures some closeness but not too much, so that Lucky is kept at a serviceable distance:

Lucky I think never releases the burdens from his hands unless forced to enact something against his will because he must never use those hands as instruments of touch. When nearly touched he becomes intensely violent.

But see the lovely photograph of Marc Brenner’s below. It could not be more clear the actor’s hands are both ‘capable of earnest grasping’, to use Keats’ words, but hanging back from doing so. Even their lift to each other and away from their own bodies is halfway to a touch. Again I need to test this out in seeing the production.

But I can’t leave this without returning to that ‘honeymoon’ that Estragon is planning early in the play. The etymology of the word according to etymonline.com is no older than the 1540s. Here’s what the online service has to say:

honeymoon (n.)

“indefinite period of tenderness and pleasure experienced by a newlywed couple,” 1540s (hony moone), but probably older, from honey (n.) in reference to the new marriage’s sweetness, and moon (n.) “month” in reference to how long it probably will last, or from the changing aspect of the moon: no sooner full than it begins to wane. French has cognate lune de miel, but German version is flitterwochen (plural), from flitter “tinsel” + wochen “week.” In figurative use from 1570s. Specific sense of “post-wedding holiday” attested from c. 1800.

It is clear that the reference to some kind of illusion is always intended, associated to the classic associations to the moon of changeability of state. The word as used in the Beckett play for me becomes part of other networks of moon references that guide the play’s treatment of time, duration and change, The Moon ends both acts in rising. At the end of Act Two, the point is almost painfully poignant. The moon causes a change – the men must part for the night, the time at which usually couples sleep together. They will not ‘go far’ from each other for, as Didi says: ‘We have to come back tomorrow’. This regulation of parting and meeting is a bit like that in Browning’s cognate parting and meeting poems though the timing of each action is inverted between them. But Estragon, always the more emotional actually feels still that the two might go away together – presumably on that honeymoon. Hence when he says, ‘Where shall we go?’, he can be taken to mean were shall we go together.[23] Didi puts a stop to that, ever aware that Godot might punish them and MUST be waited for. And while they wait for Godot, the two will never be in a relationship that matures. That is why Godot is not God, as Beckett insisted to Ralph Richardson.

In Act One, the moon ‘rises at back, mounts in the sky, stands still, shedding pale light on the scene’. Pallor matters in this play. It is that which never rises into full-blooded life. Estragon ‘contemplates the moon’ whilst Vladimir says: ‘What are you doing?’ For me, Gogo’s answer is central to the play (hence I use it in my title):

‘[The moon rises at back, mounts in the sky, stands still, shedding a pale light on the scene.] …. ESTRAGON: “Pale for weariness” VLADIMIR: “Eh?”

ESTRAGON: Of climbing heaven and gazing on the likes of us.”[24]

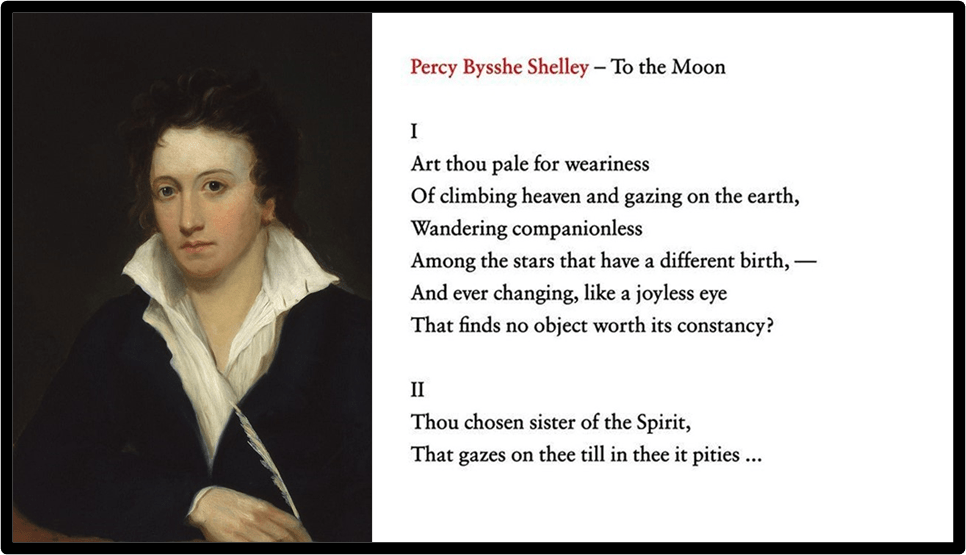

The response of Gogo is a near quotation of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s fragment To The Moon, which I place below:

Laura Quinney put this near quotation into her consideration of her thesis that BOTH Shelley and Beckett have a similar grasp of the theme of what time means in human experience: ‘because of the nature of time’ characters in both writers’ works ‘are confronted with’ what she calls ‘cognitive bafflement’ – ‘a purgatorial temporality in which nothing more can take place’. For both writers their characters and narrators ‘don’t know what is happening to them’.[25] Yet Quinney really does little more than correct the Grove Companion to Samuel Beckett in its assertion that the reference is there only to show that Shelley is ‘an English poet drawn on when a romantic cliché is needed’. She rightly says however that ‘Beckett’s attitude towards this poem cannot be merely satirical’ but is instead ‘equivocal’.

Estragon amends the quotation to add that the moon is weary specifically, ‘Of climbing heaven and gazing on the likes of us’, but that sentiment of existential disgust is not so far from the spirit of Shelley’s poem.[26]

I see more that ‘existential disgust’ in both texts but not for the same purpose. Becket was clearly calling on a greater knowledge of the poem, in Estragon if not Vladimir. The latter is more practical and with an ear to the demands of the ‘status quo’, including its heteronormativity, but Estragon still has dreams of escape for which he is punished by nightly beatings by an unquantifiable number of young men. When Estragon sees the moon weary and pale for ‘looking on the likes of us’, the key word here is ‘us’: a pair in a togetherness that never ever really gets it together beyond a swift embrace so that the two men are less an ‘us’ than two isolated men bound by a relationship they refuse to understand. No wonder the moon is pale and weary. And Shelley’s moon is, unlike these two men ‘Wandering companionless’ in preference that sticking together in one place that is like purgatory, waiting for a thing that never happens, Godot who never comes though promises too and still asserts his patriarchal authority, not unlike Pozzo. That moon is ‘ever changing, like a joyless eye’: the point is that that there is a homophone here which suggests not only what the moons sees but what it has become: a ‘joyless I’ not a ‘we’ or ‘us’, for the moon ‘finds ‘no object worth its constancy’. This moon is quite the flirt then if still joyless and lonely – a kind of Childe Harold, Shelley might have thought as he looked to his friend Byron. But as for Estragon’s point, his the ‘likes of us’ points to a couple who are not a couple, an ‘us’ that is not ‘us’ for in fear of a demand for constancy that is not waiting for some obscure event, of which they have no knowledge of its probable content – the coming of Godot.

In my reading Shelley’s poem is integral to the play, just as Quinney sees it, but integral because it focuses on the relationships of the men in it – Didi and Gogo for whom there is hope and Pozzo and Lucky for whom there is none. He reason that there is no hope for Pozzo and Lucky is that their relationship has long hardened into the conventions of an unequal society – equal only in disabling its participants other than in taking a ‘fall’ over and over again.

Whether my reading will help me with this production i don’t know. In many ways I hope it doesn’t for then the production will have shown me a different way of viewing the play: one I might prefer. I can always hope. But I will enjoy it. As I say, I have long been a fan of Whishaw from afar as this magazine in my book collection might evidence:

I am also a fan of the great Beckett – and have been for longer than for Whishaw. I cannot wait to see the play for myself

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Samuel Beckett (2000: 45f., first published 1956) Waiting for Godot: A tragicomedy in two Acts London, Faber & Faber

[2] Michael Billington (2024) ‘The waiting is over! Have the times finally caught up with Godot?’ In The Guardian (Mon 29 Jul 2024 06.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/article/2024/jul/29/waiting-for-godot-samuel-beckett-ben-whishaw-james-macdonald

[3] Alexander O’Loughlin ‘Waiting for Godot is a beautiful, haunting, and wonderfully funny production that reminds us of the play’s enduring power’ in The Tatler (25 September 2024) available at: https://www.tatler.com/article/review-waiting-for-godot-london-theatre-royal-haymarket#

[4] Arifa Akbar (2024) ‘Waiting for Godot review – Beckett’s classic tragicomedy is more comedic than tragic’ in The Guardian (Fri 20 Sep 2024 00.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2024/sep/20/waiting-for-godot-review-becketts-absurd-desolate-existential-tragicomedy

[5] Sarah Crompton (2024) ‘Beckett’s classic returns in a new production from James Macdonald’ In What’s On Stage (20 September 2024) Available at: https://www.whatsonstage.com/news/waiting-for-godot-with-lucian-msamati-and-ben-whishaw-west-end-review_1632794/

[6] Fiona Mountford (2024:41) Review in the i newspaper (Monday 23 September 2024), page 41.

[7] Nick Curtis (2024) ‘Waiting for Godot at Theatre Royal Haymarket review: the best staging of this challenging classic I’ve ever seen’ in The Standard (20 September 2024) Available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/culture/theatre/waiting-for-godot-theatre-royal-haymarket-review-b1183120.html

[8] O’Loughlin, op.cit.

[9] Beckett 2000 op.cit: 2

[10] Ibid: 50

[11] Daniela Castelli (2023 1f.) :Insufferable: Beckett, Gender and Sexuality, Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Delhi & Singapore, Cambridge University Press (Kindle ed.)

[12] Beckett 2000 op.cit: 9

[13] Ibid: 25

[14] Ibid: 47

[15] Akbar, op.cit.

[16] O’Loughlin op.cit.

[17] Beckett 2000, op.cit: 51

[18] Akar, op.cit.

[19] O’Loughlin, op.cit

[20] Beckett 2000 op.cit: 1

[21] Ibid: 9

[22] ibid: 51

[23] Ibid: 85

[24] Ibid: 45f.

[25] Laura Quinney (2021: 183 [Abstract]) ‘Heaps of Time in Beckett and Shelley’ in Sophie Laniel-Musitelli & Céline Sabiron (Eds.) Romanticism and Time Cambridge, UK, Open Book Publishers, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0232 , 183 – 202.

[26] Ibid: 186. For the line from the play see Beckett 2000 op.cit: 46.

10 thoughts on “A blog stating a case for a ‘queer’ reading of the classic play by Samuel Beckett ‘Waiting for Godot: A tragicomedy in two Acts’. Seeing Ben Whishaw at the Haymarket 25th October 2024”