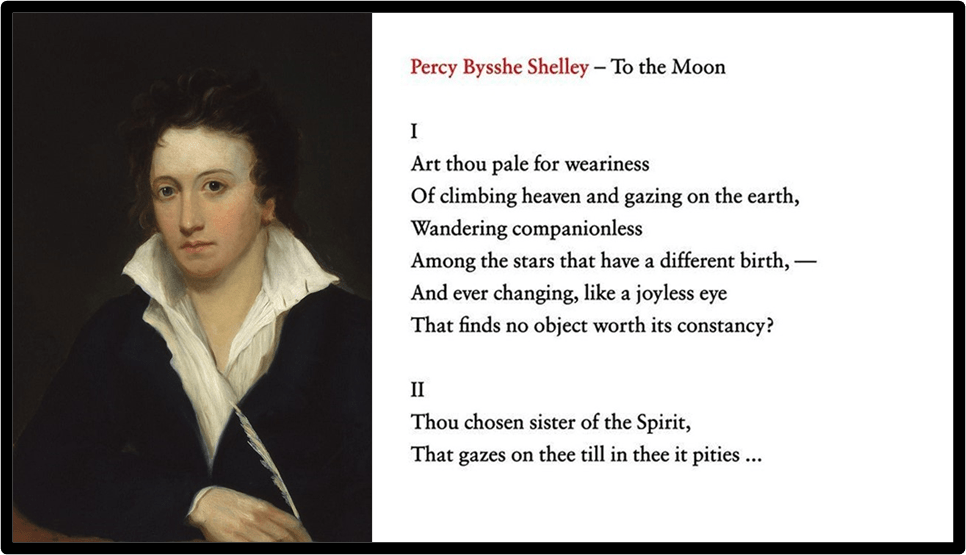

I looked at the play Waiting for Godot in an earlier blog (available at this link). I often do this, preparing myself by looking at my expectations of a production based on knowledge of its text and the prognostications of such critical review material of the actual production that I have seen. It amuses me now to look back at that blog and ponder why I made such play in it of the role of the Moon, as in this section, that refers to the text from the play and its stage directions which I cite and which in well-know ways refers directly to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s To The Moon, both texts offered again below before my statement from the early blog:

‘[The moon rises at back, mounts in the sky, stands still, shedding a pale light on the scene.] …. ESTRAGON: “Pale for weariness” VLADIMIR: “Eh?”

ESTRAGON: Of climbing heaven and gazing on the likes of us.”[1]

The response of Gogo is a near quotation of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s fragment To The Moon, which I place below:

…. When Estragon sees the moon weary and pale for ‘looking on the likes of us’, the key word here is ‘us’: a pair in a togetherness that never ever really gets it together beyond a swift embrace so that the two men are less an ‘us’ than two isolated men bound by a relationship they refuse to understand. No wonder the moon is pale and weary. And Shelley’s moon is, unlike these two men ‘Wandering companionless’ in preference that sticking together in one place that is like purgatory, waiting for a thing that never happens, Godot who never comes though promises too and still asserts his patriarchal authority, not unlike Pozzo. That moon is ‘ever changing, like a joyless eye’: the point is that that there is a homophone here which suggests not only what the moons sees but what it has become: a ‘joyless I’ not a ‘we’ or ‘us’, for the moon ‘finds ‘no object worth its constancy’. This moon is quite the flirt then if still joyless and lonely – a kind of Childe Harold, Shelley might have thought as he looked to his friend Byron. But as for Estragon’s point, his the ‘likes of us’ points to a couple who are not a couple, an ‘us’ that is not ‘us’ for in fear of a demand for constancy that is not waiting for some obscure event, of which they have no knowledge of its probable content – the coming of Godot.

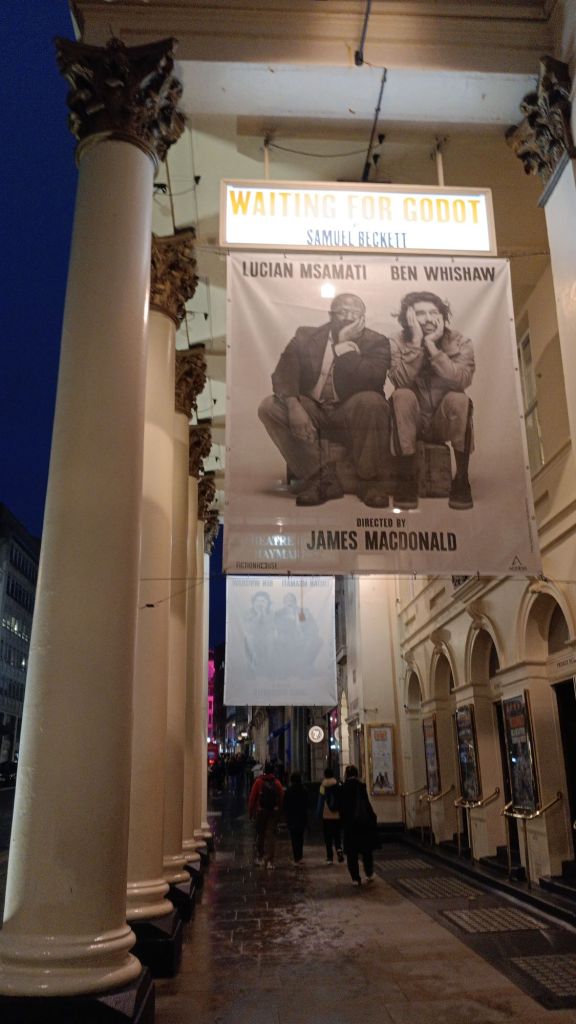

That reading of the play may be unique to me. The reason I know that this production does not share it, is that the text I quote is actually cut from Jame’s MacDonald’s play-script for his Waiting for Godot and not spoken in the play. Even Beckett’s stage direction is considered worth ignoring as if it referred to a Beckett stage without the sophistication of what this version sees as merely a lighting effect in the play – referring to the passage of time of course, but not to other associations of moons, or ‘honeymoons’ to which I also attach my reading for this feature of the play to me.

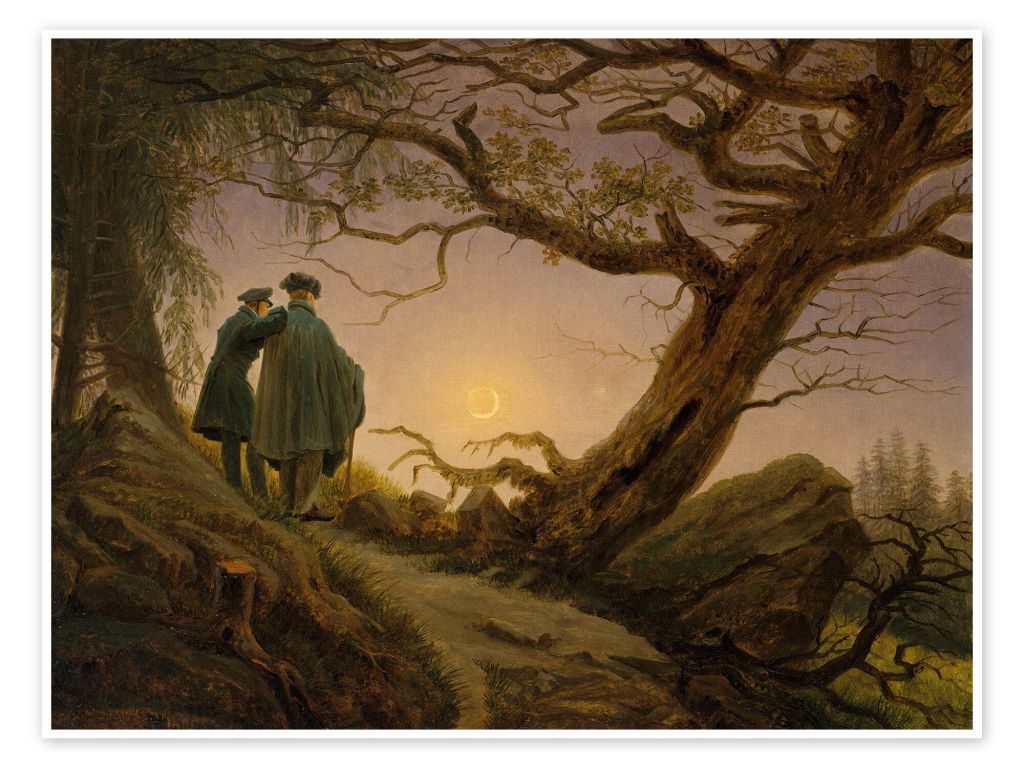

This is despite the fact that James Knowlson, Beckett’s biographer, in his programme note for this version’s programme, points out a fact that I did not know previously that Beckett ‘revealed that Caspar David Friedrich painting of Two Men Contemplating The Moon inspired the visual setting of Waiting for Godot“. [2]

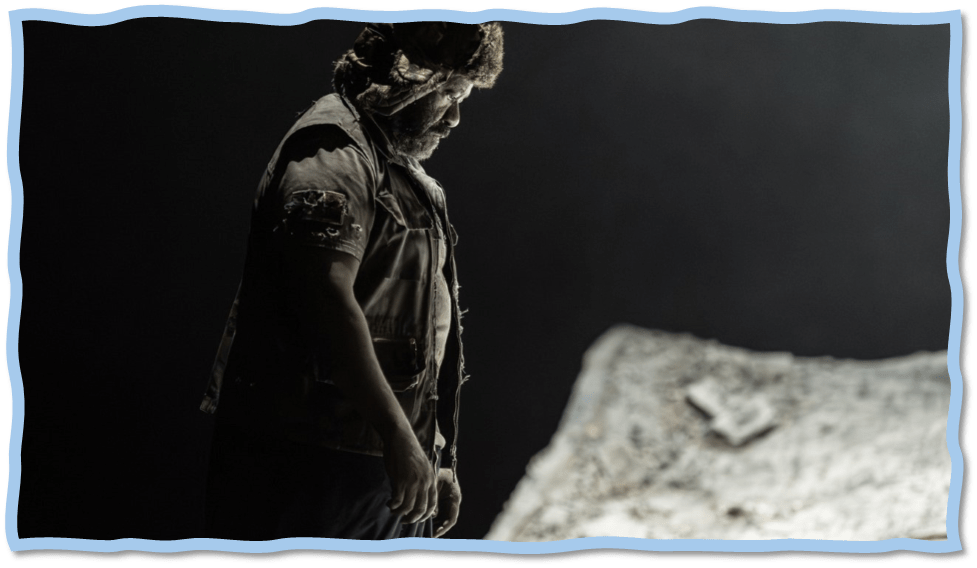

That ‘contemplating the moon’ was part of what Knowlson may mean about the ‘enduring imagery’ of the play. In the Friedrich image the men contemplate the moon as a sign of their relationship to the physical and natural world. This never happens in the play-script used nor in the action delivered By Whishaw and Msamati. The moon however features as an indicator of time’s passage, even if not hailed, labelled as a ‘moon’ (offering associational potentials thereby) or singled out. It is clear from the Scene from which the still below is taken (it must be Act 2 for the tree bears leaves which it only does in Act 2) that moonlight effects matter to the directorial crew and lighting director, Bruno Poet, and that they were perfectly adapted to the set design by Rae Smith.

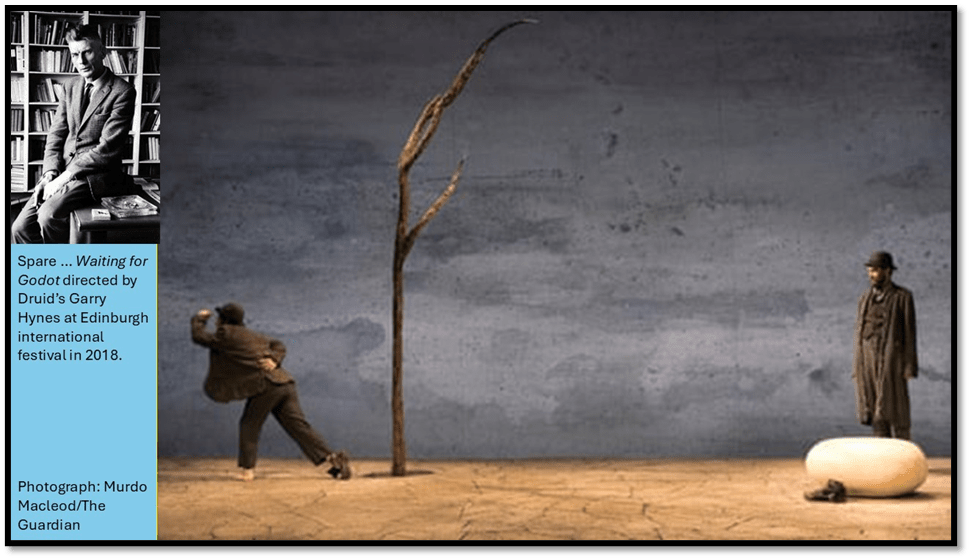

The set avoided the usual flat landscape of any other production I have seen, which use sets more like the set below.

The set in this MacDonald production played up the diagonal in its lateral and vertical placement; laterally, the set even hangs over the proscenium edge right of stage, where Gogo leaves his boots, vertically it is a series of raised inclines and depressions of differing size and significance. It all contributes to the notion of voids that overplay all of time and space and suggest a world that lacks any solid basis that might hold it it up from chaotic fragmentation. Hence the silver light of the superb ‘moonlight’, if that is what it was, was always undermined in the sequence of the play by the red lights that characterised the entrance of Luca Fone, playing the ‘Boy’, emissary and servant of Godot who may be one of two twin brothers, and his or their disappearance over the top of the incline at the rear of the stage into the cirumnambient void itself when he or they leave. There seems no clear sense that a place or a time is any place or time that we might otherwise recognise in this production – the space and time as liable to be metaphors of accidents of space and time rather than expected determinants of the framing of real embodied experience.

The production programme’s other significant note is from Fintan O’Toole who quotes Beckett saying of art that is ‘characterised by “the expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to expression, together with the obligation to express”‘. [3] If those who must express a view of the world we share have no topic, medium of expression, or capacity of power or desire to express them but still MUST express something somehow, then we are left with something like Vladimir’s statement about all the knowledge time and space allow us to sense their meaning as we ask: ‘What are we doing here, that is the question’. Maybe because it was Ben Whishaw saying this, this echoed the line of which it may be a rephrasing: ‘To be or not to be, that is the question’. Except that Hamlet never is so uncertain that there is a place and time he is expected to play out a pre-written role in. It is bold to say to an audience of a Beckett play:

We wait. We are bored ... No, don't protest, we are bored to death, there's no denying it

For no audience will not be aware that the place and duration of the play yields no real reason for us to pass the time as we do, as I did in The Theatre Royal Haymarket on the 25th October. The play was well received with numerous catcalls to the players, standing ovations and expressed pleasure but, under it there is Vladimir (Didi) again:

All I know is that the hours are long, under these conditions, and constrain us to beguile them with proceedings which - how shall I say - which may at first sight seem reasonable, until they become a habit. You may say it prevents our reason from foundering. no doubt. But has it not long been straying in the night without end of the abyssal depths?

There has never been such a play for asking us why we spend our hours in a theatre waiting dor something to make sense of our lives, to save us, as Godot is mean to save us. But likewise there has never been such a play to emphasise that the secret is the maintenance of an ‘us’ as having more present bearing on life that the maintenance of a lonely ‘I’ ‘wandering companionless’. And even without Shelley’s moon, this play well done shows that we are bound to each other. In the worse event, we are bound as Pozzo and Lucky are bound, by the convention of a hierarchy that gives us roles – but in this production, in Act Two at least, Lucky and Pozzo play those roles with a kind of mutual care. The bond which survives in the heart however is that of Gogo (pronounced to sound like Godot in this production) and Didi. And I think Fintan O’Toole shows me that there is in the play a queer note still – which is its persistent questioning whether we are responsible or not for the violence and cruelty that we believe to be attracted by being ‘different / other’ than the norm. It is a question O’Toole believes was directed by Beckett at the impossibility of understanding the persecution of otherness by the Nazis in Germany and conquered France, a power he resisted in the French resistance until betrayed. Here is the nub he quotes:

ESTRAGON: I wasn't doing anything. VLADIMIR: Then why did the beat you? ESTRAGON: I don't know. VLADIMIR: An no, Gogo, the truth is there are things that escape you that don't escape me ... ESTRAGON: I tell you I wasn't doing anything. VLADIMIR: Perhaps you weren't. but it's the way of doing it that counts, the way of doing it, if you want to go on living.

That ‘not doing anything’ is sufficient to attract repulsion and social repercussion if you do it (for ‘not doing’ is a thing that must be ‘done’ too) in a ‘way’ that others choose to dislike or worse is a thing the oppressed and marginalised know too well. And the only way to avoid a beating from the validated is to learn to do nothing in the right way not the wrong way. And for Vladimir that means not hearing the dreams of others or expressing a need to ‘escape’ the hope that something will turn up of its own accord (there is much of Mr. Micawber in Didi) but enduring it, waiting for it – patiently. And Didi is right. Gogo finds that much more difficult than he. And for me I understand that by seeing in Gogo the incurable romantic lover – the lover on the way to a honeymoon that ever evades him so that he never is a part of ‘we’ in a convincing way. Didi on the other hand realises that ‘we’ exist only by finding ways of passing the time where ‘we’ are without caring to know where and when that is. Hence he keeps trying to remind Gog that ‘were’ here and now yesterday, as we we are today and will be tomorrow. Where were he if not here like now Didi says, To which Gogo replies, refusing to think of ‘we’ but only of ‘I’:

How do I know? In another compartment. There's no lack of void.[4]

There may be no time and place in which ‘I’ exists after all, but if we desire to become ‘we’ then we must inhabit some place over some time in the present or in memory, even when all meaning is gone and every place is no more than the ‘scenery’ your acting partner speaks of unconvincingly to you.

Recognize! What is there to recognize? All my lousy life I have crawled about in the mud! And you talk to me about scenery! [5]

This production is a great one because it understands that like all the greatest plays, it understands that every thing we do – either act or wait for the action of another – is little more than a play-script where we must convince ourselves of communal identity and need for each other or go on ‘crawling in the mud’, set on by those who feel themselves entitled to own the land in a ditch or tied to a ‘master’ like a ‘slave’ because he gives us meaning in exchange for our meaningless obedience to him. This is the stuff of tragi-comedy. And in tragi-comedy, desire and hopelessness combine, and consequences. The erection scene was played perfectly:

ESTRAGON: What about hanging ourselves?

VLADIMIR: Hmm. It’d give us an erection!

ESTRAGON: [Highly excited] An erection!

VLADIMIR: With all that follows. Where it falls, mandrakes grow. That’s why they shriek when you pull them up. Did you not know that?

ESTRAGON: Let’s hang ourselves immediately[6]

This was a production where touch mattered enormously and both the touching, and refusal thereof, between Didi and Gogo was so obviously set against the mediated relationship of Pozzo and Lucky, with its ropes, hierarchy and use of commands. And it was also a production where the function of touch as connection was played forcefully – its cruelest moments those of confused loneliness as in Estragon or arrogant denial as in Vladimir.

I loved this Godot. HERE I sat entranced.

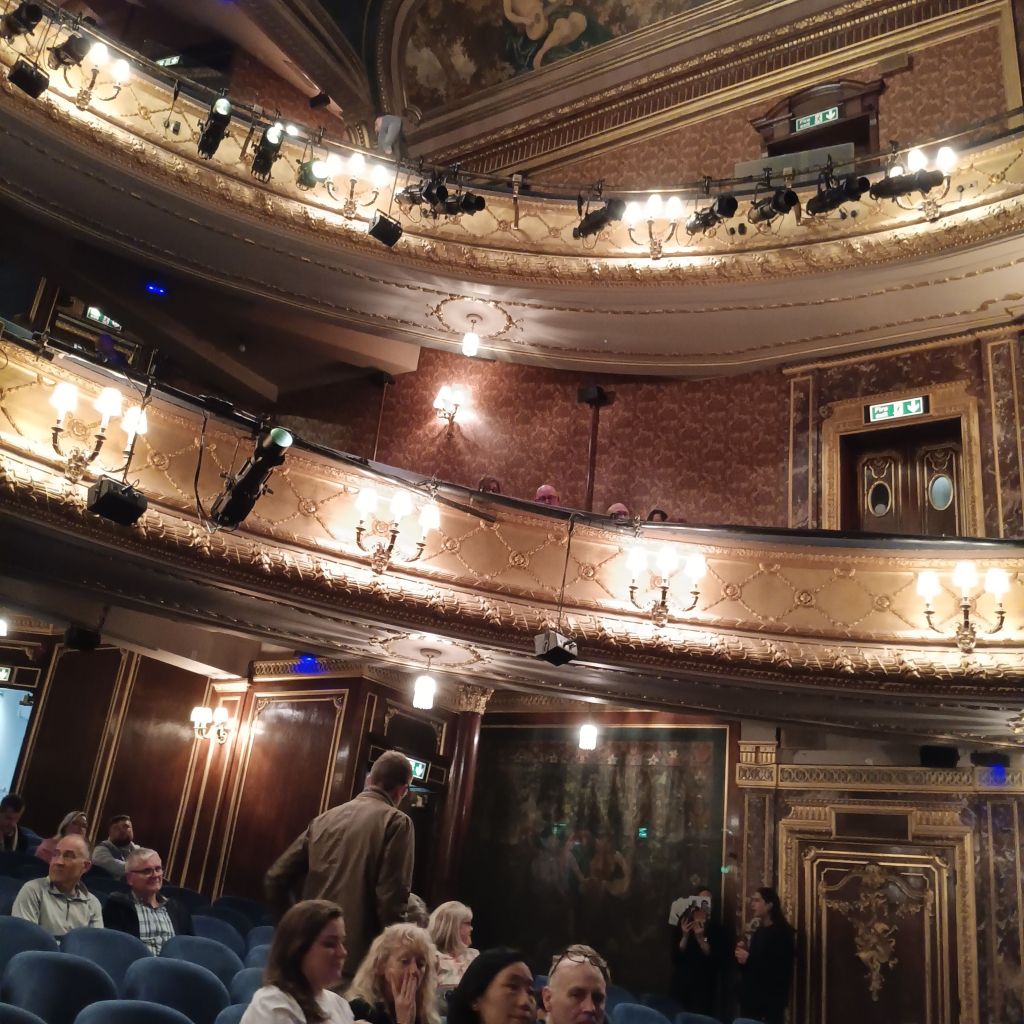

And the theatre. I LOVED IT despite myself.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Samuel Beckett (2000: 45f., first published 1956) Waiting for Godot: A tragicomedy in two Acts London, Faber & Faber

[2] James Knowlson (2024) ‘The Enduring Imagery of Waiting for Godot’ in Theatre Royal Haymarket Programme

[3] Fintan O’Toole (2024) ‘The Obligation To Express: Beckett’s Politics’ in Theatre Royal Haymarket Programme

[4] Samuel Beckett op.cit: 57

[5] ibid: 52

[6] ibid: 9

2 thoughts on “‘[The moon rises at back, mounts in the sky, stands still, shedding a pale light on the scene.]’ In the Theatre Royal Haymarket production of ‘Waiting for Godot’, is the unlabelled moonlight compensation enough for an absenting a visible moon?”