In my blog on Victoria Chang, I spoke of her use of largely regular iambic pentameter lines of verse in Section II of her new volume With My Back To The World, in an elegy or obit called Today, and based on the Date Paintings of On Kawara.

Do schools teach metre and basic metrical analysis now when they teach poetry on literature courses, especially if the literature is English and not a language habituated to distinguishing the quantity, quality or both of sound signified by alphabetical signifiers used in writing, aa in Greek, German or French? I have my doubts. I once acted as a moderator for One Awards where it was considered old-fashioned to encourage even the most basic kinds of teaching about even ‘knowledge about language’ beyond the intellectually thinnest notions of register in schools at secondary education level. Skill in clause analysis was considered too much to expect in the skills of trained teachers, or other moderators, of English, even English Language. If this remains true, it does a disservice to learners.

However, the relevance of that issue here is that I started wondering whether a phrase or two I used in that blog would be understood. In particular this comment. To tell truth, I was already concerned about it because I spoke from memory about how poetry was discussed when I was a learner at University College London, taught by people like Winifred Nowottny and A. S. Byatt. Take this example sentence or two:

The idea of ‘touching time’ is the essence of the book, and see how the iambs assert themselves in this section, in order to beat time, or maybe more accurately tempo, so that it is like a heartbeat, which is how Wordsworth and Tennyson thought the iambic pentameter worked to engage us empathetically, according to A. S. Byatt.

Now I was already concerned about this because there is no supporting reference for Byatt’s view in my blog. It was though commonplace to hear her speak of this idea, and have to explain it, when she taught Romantic and Victorian poetry, as she did to us all that time ago. But I could have given a reference. I was just too lazy.

The key essay containing the idea is her essay on Tennyson’s Maud in Isobel Armstrong’s clear riposte to the denigration of Victorian poetry (notably in Leavis’ Revaluation) by F. R. Leavis and the Scrutiny group, The Major Victorian Poets: Reconsiderations. An example passage is that below in which, in lectures (if not quite in this printed essay) Byatt would extend into the metrical analysis of the lines quoted here as auditory prompts to the notion of the flow of rivers as emblem of the flow of blood, and the temporal promptings of the biological heart, rather than the ‘heart’ in its sentimental understanding. In questions in lectures, she referred these very lines to Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey, whose scansion entirely mimes the motion of the blood, even its surprise leaps (but you can try that for yourself afterwards):

... I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

...

In doing so she argued that the inversion of logic in the transposition of the modifiers ‘along’ and ‘in’ dramatised the function of the heart as explicated by Harvey to regulate blood flow across different domains. After all, she said, you should expect to feel things ‘in’ the heart not ‘along’ it, and vice-versa with the blood flowing ‘along’ biological tubing like veins. We needed to understand this, she insisted, to understand how the sound of the verse captured the difference of everyday blood flow rate to that in the sexual excitement felt by the child-like narrator in Maud.

Text from A. S. Byatt (1969: 87f.) ‘The Lyric Structure of Tennyson’s Maud’ in Isobel Armstrong (Ed.) ‘The Major Victorian Poets: Reconsiderations’ Abingdon & New York, Routledge, 69 – 92.

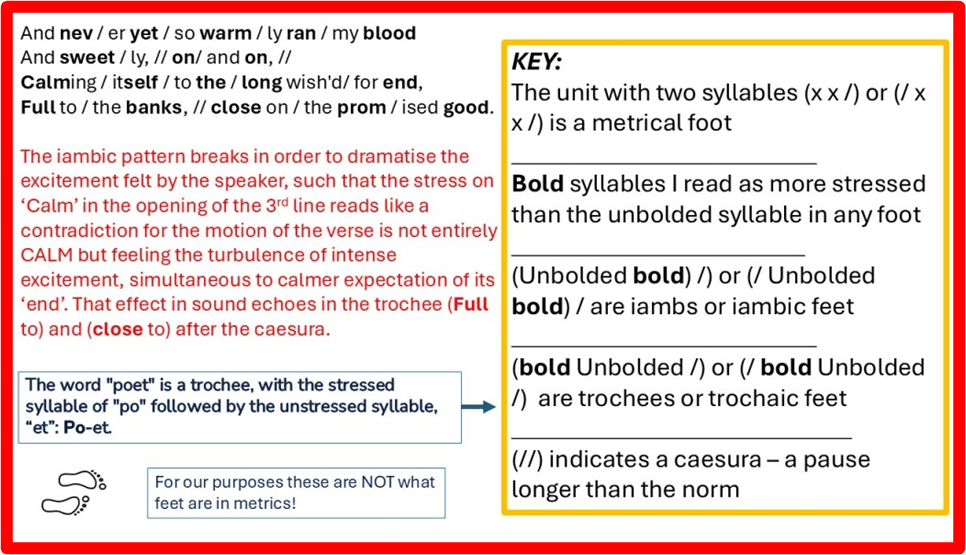

And back in my lonely college room I tried the idea out by scanning the Tennyson:

And nev / er yet / so warm / ly ran / my blood

And sweet / ly, // on/ and on, //

Calming / itself / to the / long wish'd/ for end,

Full to / the banks, // close on / the prom / ised good.

Here is a a reproduction of the lonely findings in box form, with an explanatory key missing from earlier statements:

And remembering this made me think again about a poem that is almost the key to my love of poetry in its development in school:

A Slumber did my Spirit Seal

By William Wordsworth

A slumber did my spirit seal;

I had no human fears:

She seemed a thing that could not feel

The touch of earthly years.

No motion has she now, no force;

She neither hears nor sees;

Rolled round in earth's diurnal course,

With rocks, and stones, and trees.

It is a favoured poem in my memory, from which it often enters my consciousness totally involuntarily, because it more clearly than any other poem addresses with such economy what we mean by feeling and its claimed absence or presence in poetry- a thing it can’t fail to do because it rhymes ‘feel’ with ‘seal’, as if not feeling were a clear kind of over-contained thing. Sealed feelings are not jist feelings boxed in but with the box over-securely sealed. Such feelings are not absent feelings but suppressed ones and this is how this poem works to allow us to understand the lyricist’s voce, that person who uses ‘I’. At school our teacher Geoff Mountfield was his honoured name, spoke of the homophone between the word ‘seal’ and ‘seel’, a verb used in hunting with a hawk to indicate the blinding (originally by drawing threads through the bird’s eyelids or by cap of course) of the hawk.The containment here is even more fearsome.

It is a poem about time of course, our fear of the effects of its constant passage to some end that is, or is a kind of, death. What is the repressed in the poem is that the lyricist understands Lucy as intangible not just to ageing and death, to mortality, but to his own touch or hertouch on him, desired but not attempted: As we read the poem, we understand that somewhere deep, the lyricist understands and wants Lucy to be something the ‘does not feel’, as if the verb ‘feel’ were intransitive and not modified as transitive by the object in the run-on (enjambment) of the lines. This level of contradiction makes the verb ‘seemed’ work hard.

But when we achieve a totally unfeeling Lucy, to wit one dead and buried and entirely motionless except for the motion given to her like all nature, but also to dead ‘rocks’ and ‘stones’, we realise the pain involved as thecreslity of unsought endings impinge on the contradictory wishes of our earlier lives. Had we known Lucy would die, would we have acted differently? I have though that about a person lost to me by death, myself even in my older age.

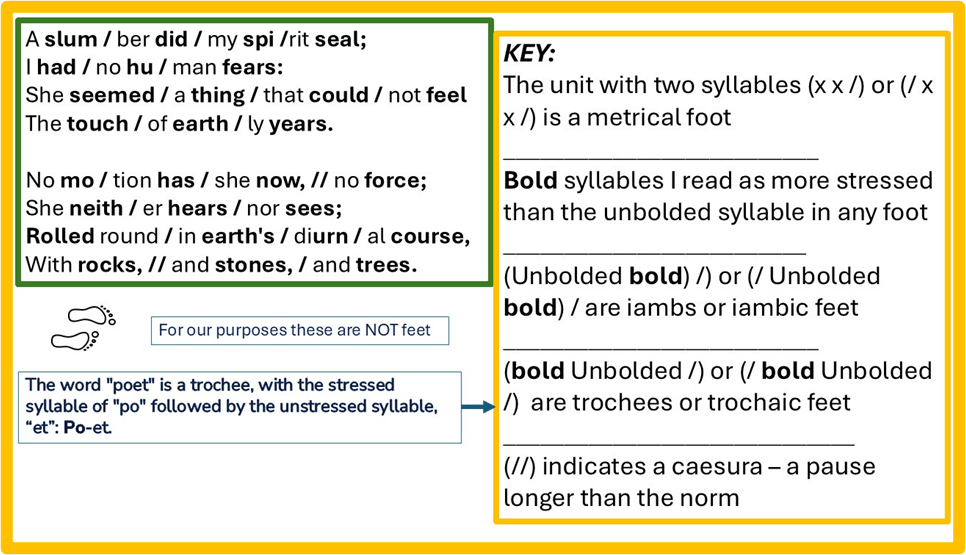

But my point is that this poem dramatises all this through poetic measures or metrics. Here is my scansion – first in text and then as a box, like the one above on Tennyson.

A slum / ber did / my spi /rit seal;

I had / no hu / man fears:

She seemed / a thing / that could / not feel

The touch / of earth / ly years.

No mo / tion has / she now, // no force;

She neith / er hears / nor sees;

Rolled round // in earth's / diurn / al course,

With rocks, // and stones, / and trees.

Without the constant reassertion of iambic lines (with 4 feet in he first and third lines of each stanza, three in the second and fourth), we could not feel as much the lulling soothing force of repressed, sealed, or ‘seeled’ feeling, that makes us a thing that ‘sees’ nothing like the buried dead. Without it the word ‘force’ in the last stanza would lack felt ‘force’. That the poem ends with the fact that ‘trees’ (living things) are also ‘Roll’d round’ in the earth’d daily motion, is in itself a triumph for it emphasises that it it is not life that is lost in Lucy that matters as much as the ability to move (and I think ‘to move us’ – to be the object that seems to call forth our lyric and embodied emotion, and even deep sexual feeling).

I wrote this as reparation for my laziness yesterday, but to also hold back on my next blog on Mark Haddon’s 2024 collection of short stories, Dogs and Monsters. But there is a link to that upcoming blog too for both Wordsworth and Haddon want us to understand how and why we need the concept of the ‘human’ to organise our feelings as meaningful in stories we tell to ourselves and others. In Wordsworth, the point of his very short story lies in the thought of what it means to ‘have no human fears’ (which is to be a kind of invulnerable monster), and it would seem that such fears are embedded in the notion that our imagination must get used to feelings, including our fears, that occur in time (in the experience of ‘earthly years’ for instance) and embrace them whilst within the flow of time itself – in the varying heartbeat of a poet’s verse..

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx