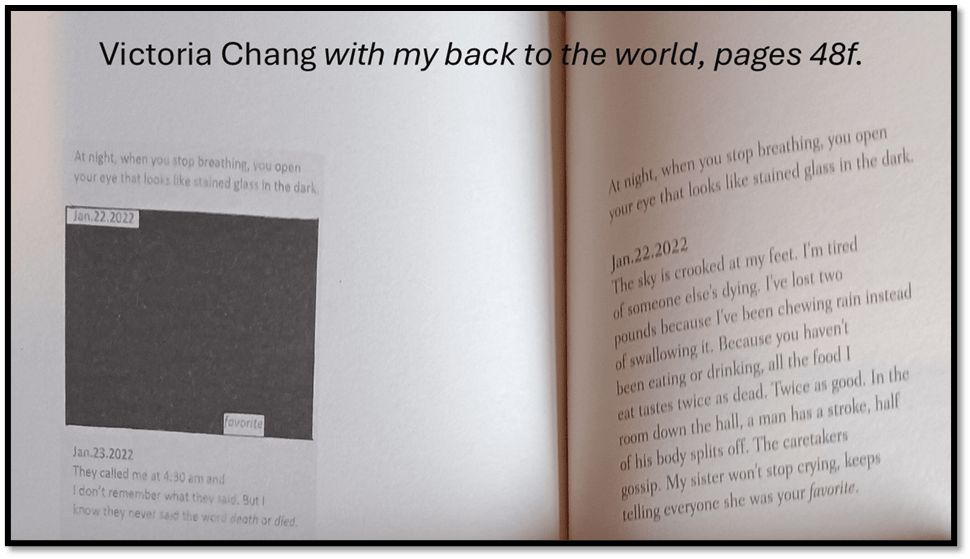

‘Agnes must have miscalculated’:[1] The math that we get wrong in art, perhaps deliberately. This is a blog on Victoria Chang (2024) With My Back To the World London, Corsair Poetry.

Ekphrasis is an exercise in written words, used in poetry since Ancient times, to describe visual art in a way that tests whether words alone can’t make ‘pictures’ in the mind of its audience. In a sensitive review in World Literature Today, Kathryn Savage describes Victoria Chang’s poetry in With My Back To the World thus:

Ekphrastic in nature, Chang’s new poems are printed alongside collaged imagery and time-stamped early poem drafts, inspired by conceptual artist On Kawara’s Today series.

Try as I might I cannot get this insight to clarify whether to be ‘ekphrastic in nature’, qualifies whether these poems constitute ekphrasis or not. I do not say that in criticism of Savage, because I think Chang wants her poetry to use ekphrastic technique to question the nature of each and every mode of art and the boundaries between them. In ekphrasis we usually assume that our interpretation of a picture replicates the thought processes of the visual artist we work with to produce writing, not debate with them whether they know what art, even their own art, is and means. For this is what Chang does with Agnes Martin and On Kawara, challenging them as much as explicating them.

There is no getting away though in fact that these ‘poems’ even challenge what we mean by poetry, perhaps even the processes thought to constitute the ‘work’ that is the process and end result of what we mean by art of any kind. Chang, more that any poet I know, challenges even herself as the repository of the things that make one a poet. There is, for instance, a tremendous extant interview with Hiedi Seaborn of The Adroit Review from 2020 following her lauded volume Obit, where it is almost impossible to know exactly what ‘triggers’ her poetry other than her refusal of the traditional poetic form of the ‘elegy’ with her own invention in form, the ‘obit’ ( a play with the journalistic form, the obituary).

I wrote obits right away from the very beginning, because I didn’t want to write elegies. I didn’t want to write about my mother at all, or the feelings that I felt. But that word triggered something in me. Once I started writing, I didn’t even have time to sit down and make a list of things I thought. I literally just went one after another, bam, bam, bam, because of how I felt. I was really much more driven by my feelings, versus my mind. But the poems are very thinky. (my emphasis).[2]

That dialectic – almost an angry debate – between combatants, but here between thought and feelings but in the new poems between Chang and Agnes Martin (to name but one) are the essence of these poems, as they do not put pictures into words as argue what pictures and words are with any one imagined to have the bravura and status to be worth debating. There is in Chang, a kind of biting self-critique that fuels her debate with beloved others: a sense that there is something deficient in her, not yet developed or matured (and other artists, who in the same interview she describes as, of necessity:

literally, the most narcissistic bunch of people I’ve ever known. God bless us, and I love us all to death, but that’s something that really bothers me. I think we’re wired that way because we have to be, because we have to spend so many hours in our own heads.

Artists spend lots of time entraining the facets of divided and divisive personalities how to both think and feel, and to combine both but possibly succeed best when they fail in achieving harmonies of any kind in the process. Just how deep this goes, can be tested in the following much longer passage from that interview, one I find extremely challenging to read:

I also think that I hadn’t experienced real hardship until my dad had a stroke, and that was in my late 30s. Then my mom died, and that was another level of hardship. It’s awful to say that things like those are good for you, but I do think that all of those awful experiences were really good for me as a human being. Because I was very much in my head all the time. I feel like I can actually go to my heart and not feel so vulnerable. Because for me it’s always about vulnerability. I was taught to be strong, and to be that pillar, all the time. So, to actually show and reveal what I really feel, and to be vulnerable, was just not in my vocabulary growing up. It took my mom’s passing to be just a smidge more comfortable with that. I’m still never going to tell people stuff, because I’m not that open of a person, and so I think that Obit was more revealing, for me, than my other books.

….

I think that I was forced to grow up, and I’m still growing up. I’m certainly not even remotely… I mean, we grow up and we are grown, and then we die. Why am I working so hard at life if I am just going to die? It’s a really strange question. But my mission in life, my mother gave to me, was always to be really successful at whatever I did. Work harder than everyone else, do the best you can, and just go-go-go, mostly because it’s a good thing to be ambitious, apparently, but also because we are marginalized in all sorts of obvious ways. That’s not to say I’m not a generous person, but it wasn’t like I was going to sit around and have a lot of empathy for everyone all the time and spend a lot of time wasting my time on feelings. I think that I took that mission to heart, and in fact, that mission replaced my heart. I’m hardly reformed. I’m still very much that way.

It’s astonishing to see such deep candour about what it means to live in one’s head as a poet must, constantly processing experience in a ‘thinky’ way and settled in the isolation that involves, even able to identify it as narcissism, though that might not be as damning as it once sounded (see my blog at this link). Chang sees her family life geared to a kind of ruthless pursuit of achievement that allows her to be totally locked-in the ‘wordsome’ expression of thought, feeling and sensation without ever feeling anything at all about the outer world. She is aware her parents, particularly her mother, drove this feeling but so to does her father’s stroke and her death drive her into new ways of exposing feeling to and for others in ways that no longer hide her from the world. And with that goes empathy, a desire not to see your poetry just excel but to see in it an exchange of empathy between self and other a desire to link to the feeling of the other either in connecting to what is more ‘universal’ in experience or in a new attention shared between reader and writer. After she calls out writerly narcissism, she rationalises it:

You need to be like that, I think, to be successful as a writer. Because if you cared too much about other people, you would’ve done other things, and you would never be able to chain yourself to a desk. I think we have to be that way, but that really bothers me about writers. So, I try really hard to not be that way in my writing as much, if that makes sense.

Whether we accept that characterisation of writing or not, I think if we are to get to the root of why Chang’s later work is SO powerful, we must see in her art the urge to what she will call, as E.M. Forster did, the aim to ‘only connect’, not only o connect ideas, feeling and the senses within each of their isolated domains, but together, and with other persons who might have felt or will feel the power of those interconnections, which cross distance (time and space – hence the ‘asynchronously’ in the quotation below). That is how I read, this piece, the first selected statements of which tells us that her poetry does what no other poetry she has found does, and she is incredibly well-read (a statement that might strike anyone as full of a kind of vanity, where Chang clearly NOT VAIN). She says of her poetry (here of Obits):

… it’s a way of connecting people. Although again, albeit asynchronously. That’s what I wanted to write this book for. Someone could pick up my book—in the same way I picked up Meghan O’Rourke’s book, or Joan Didion’s books—and suddenly feel connected to me.

…

But then I think, everyone’s going to care if I’m able to make people understand that these are universal feelings. So how do I do that in a poem? I remember at some points feeling like I was getting too detailed, and in the minutiae about things that only I would care about, and then I would try and lift it up a little bit more, like a drone shooting up into the air. And getting back up to a level that I felt like I could reach people.

I started though by seeing how we might query, as the proposer of the idea, Kathryn Savage, herself does I suggest, that these new poems are ekphrastic ‘in nature’ but not necessarily ekphrastic. The only way I know of doing his is to test out one of the poems where we can access the Agnes Martin referred to, though these paintings do not lend themselves to reproduction. I chose one, where I had help from an established critic in the press, here Nicole Yurcaba from the Arts Fuse digital review magazine, Leaves, 1996.

Yurcaba’s thesis is that Chang’s poems in this new volume focus really on a dialectic with social and aestheticized notions of mental distress. They do this she says so that Chang can create in her own art :

a new space, a place where depression and grief can be accepted rather than rejected or stigmatized. Hopelessness may consume the speaker, but art, and the time spent with making or encountering it, serves as a strange form of salvation.[3]

The poem plays, no doubt, on that feature of Agnes Martin’s work – who was diagnosed with schizophrenia (whatever that really means in a better world where psychiatric diagnosis is seen as a kind of rather random labelling) and who spent her later years (still working and producing the series of works that gave Chang her volume’s title) in An ‘assisted living facility’, in the words of The Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). Wikipedia gives enough of all we need to know here without otiose speculation on the value of psychiatric symptomatology:

Martin was publicly known to have schizophrenia, although it was undocumented until 1962. She even once opted for electric shock therapy for treatment at Bellevue Hospital in New York. Martin did have the support of her friends from the Coenties Slip, who came together after one of her episodes to enlist the help of a respected psychiatrist, who as an art collector was a friend to the community. However, her struggle was a largely private and individual one, and the full effect of the mental illness on her life is unknown.[4]

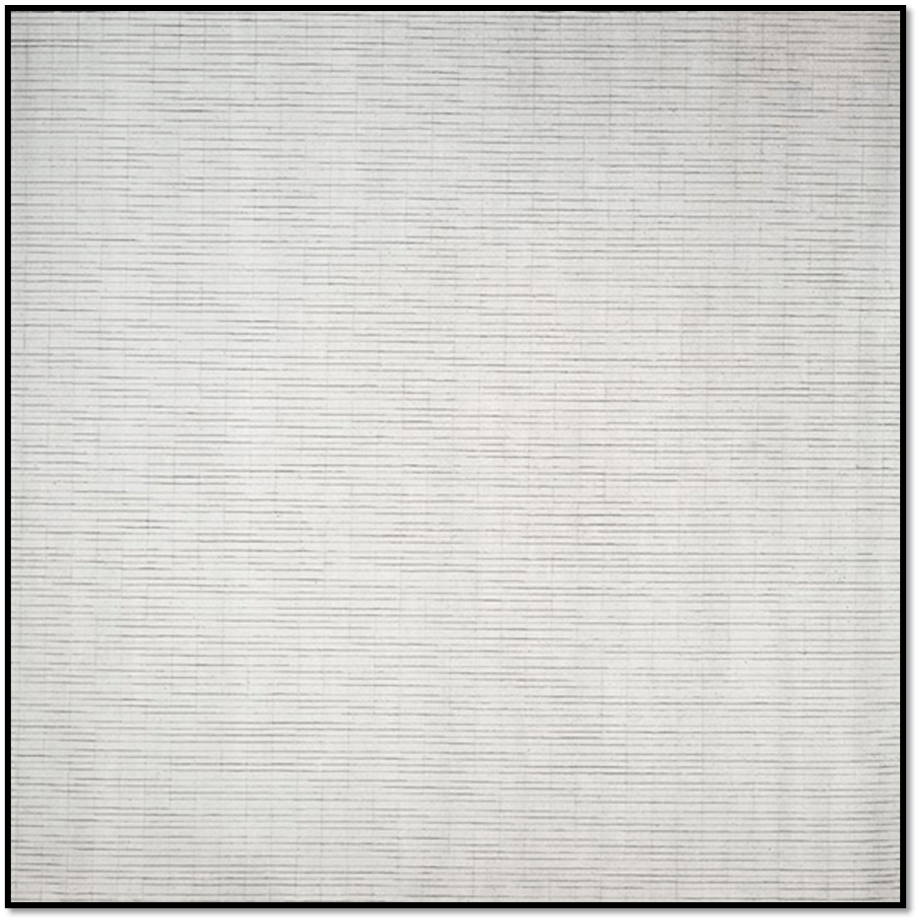

This information does not give us access to readings of Leaves, 1996, the painting. Here is a good a reproduction of the painting as I can get:

Agnes Martin ‘Leaves’ (1966) available at: https://www.wikiart.org/en/agnes-martin/leaves

It is a painting that absolutely needs to be seen in the flesh, and in truth, I have not seen it thus. But it contains the thing that all the reviews tell us Chang does with is to refer as Savage says more generally of more poems referring to perhaps this and other paintings of the 1950s and 60s and to ‘the speaker’s own experience of depression and observation of Martin’s signature pencil lines’.[5] It is typical of Savage’s delicacy as a reader that she does not say the paintings are ‘read’ by Chang’s poems (if only UK poetry criticism was this subtle). Now Yurcaba has little or no reference to what might be called ekphrastic in the poem. I think the reading is however useful enough to cite in full:

“Leaves, 1966” is an exploration of the various ways depression manifests. It opens rather peacefully: “On some days, my depression is over there in a picnic basket while I am / over here looking at art.” A sense of distance and displacement emerges as the speaker imagines ants being closer to the depression and then eating it. Still, despite the ants’ consumption of desolation, they are not depressed. That means that the speaker has been unable to transfer the condition of sadness elsewhere. The depression remains in the speaker, who is forced to take ownership of her sadness. “I miscalculated my depression,” confesses the speaker, admitting “The last time I saw it was at 10:00 p.m.” This leads to one of the speaker’s most powerful statements regarding melancholia: “I always think it’s gone. But it regrows each night. It has skin.” The depression is personified, transforming it into a constantly present, ineliminable entity.[6]

I think this fine as it stands, but it fails at all to show how reference to the painting by Agnes Martin works in it. The critique gives a fair enough summary p to the moment where the queen ant, to whom the worker ants feed the cut up leaves of which the lyricist’s depression has become the metonymy (a common form of metaphoric action in these poems) But it needed to note that the transference of emotion posited between the Queen Ant and the lyricist, may be working the other way between Agnes Martin’s Leaves painting and the lyric Leaves, 1966. For the poem shifts direction rapidly as it turns to a kind of ekphrasis of the painting and before it turns to self-critique about the lyricist’s knowledge about her own depression:

…Agnes must have miscalculated. There are 127 lines But only 3 complete sets of 4. The set on the top of the painting only has 3 lines. I miscalculated my depression. The last time I saw it was 10.00 p.m. I always think it’s gone. But it regrows each night. It has skin. It is even waterproof. In a way, it resembles leaves. But everything resembles leaves at some point, ….[7]

In my reading (and re-reading) of this I find such constant variance of response to the evaluation of art, the senses, thoughts and ‘feelings’. The thing Agnes is accused of (miscalculating the number of lines and their categorical relationship to each other) is almost trivial response to the painting – an anger directed at the painting for being what it is and not another thing. Having decided that the painting works by creating sets, using the term in part as it used in mathematics of lines, it disputes the accuracy of the categorising and/or calculation of these sets. This is a means of describing Martin’s lined or other pictures in other poems (I will refer afterwards to Untitled #5, 1998). It sees the coolness, intellectual detachment and isolation from the common and the communal as bound up in the stereotype of the mathematician, an entity that stays in its ‘head’, and whose aim is not primarily to connect with anyone or anything. It rings bells with the anger wherein Chang debates with Martin, and perhaps her former self which Martin may represent, whether art primarily means ‘freedom’, as apart from connection, or whether ‘solitude’ is the same thing as ‘freedom’. [8] It is easy for the artistic to fly to such narcissistic solipsism, given the demands of art that mean solitude is necessary for its achievement (or so Chang thinks not unlike Agnes Martin) who lived in an adobe hut away from all connection for a significant part of her life.

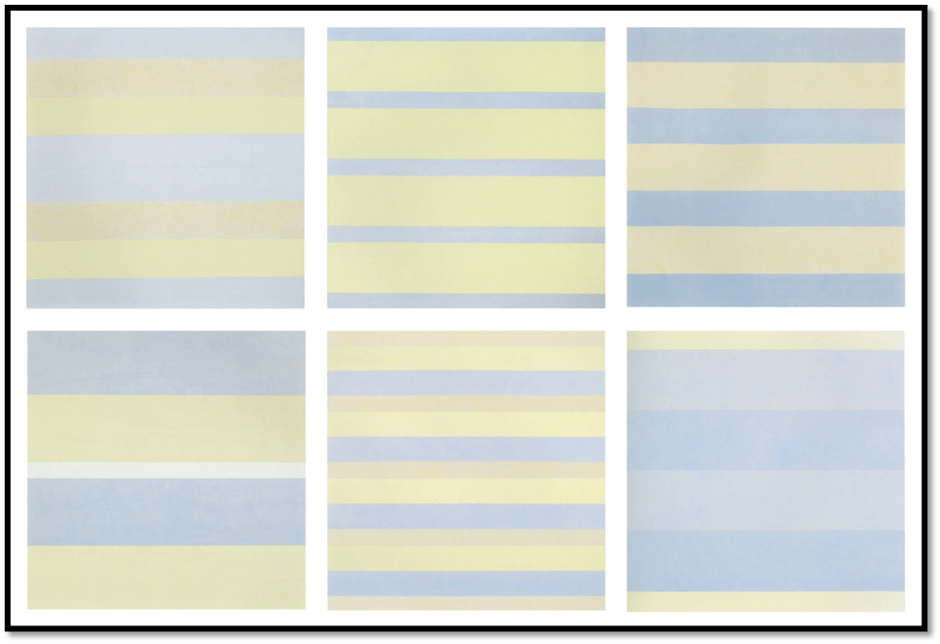

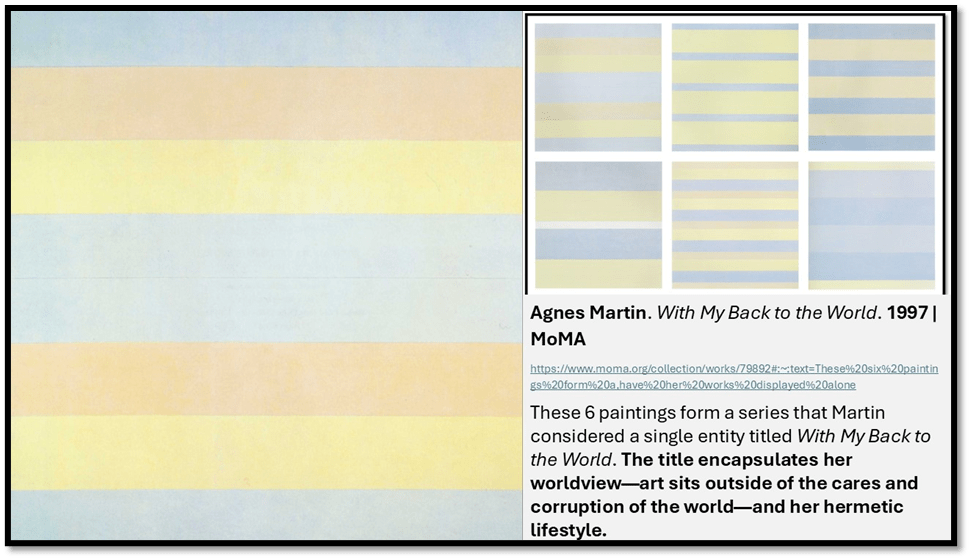

And perhaps Chang shows at other points Martin miscalculates other aspects of her line paintings. The undeniable ekphrasis in the mathematical accusation lies in the fact, as MOMA acknowledge (of My Back To The World series by Martin) that the method may appear to be merely that of identity of forms and repetitions, ‘but with time, attention, and a closer look, their many small variations reveal themselves’.[9] Gaze at the poor reproductions of that series as a whole below. Without seeing it in the flesh we would not see that the whole being of this painting of boxes, rectangles and lines of apparent monochrome sections, that the whole was created by hand with a paintbrush, that the regularities contain ‘flaws’, that are possibly of more importance than the sense of the overly controlled and regulated in abstract thought.

I think Chang knows that Martin ‘miscalculated’ as a means to find one inkling of connection between her art and individual viewers of and the communities art might serve in a fairer society. Hence for both of them the title of their works in these instances are a kind of ironic insistence on turning ‘one’s back’ to the world and looking only at your medium (whether paint or language. MOMA still, in their publicity say that her title (the one used by Chang) ‘encapsulates her worldview’ , but how can they possibly know this of her or have known it whilst she lived. Her ’hermetic lifestyle’ as they call it is often read as a preference for isolated exercises in Zen Buddhism than for social living: commonly she is thought of as living ‘above the line’ of common humanity and ‘boxed in’, sealed hermetically by her own choice. And, who knows, this may be true, but it is certain that in part Martin turned her back on the world for the reason other queer people did of her time, and others of emotions that refused to be merely those of the prescribed norms, such as her beloved Mark Rothko.[10]

In Chang’s poem on this series With My Back To The World, 1997, turning your back on living with others involves negotiating the pains of parting and the admission that your satisfaction hereafter is in ‘emptiness’.[11] Even a poet knows that when she learns that it is ‘possible for a sentence to have no words’, that may be because it resembles metonymically a prison sentence, boxed up in silence.

My impression that Chang sometimes debates angrily with Martin about her turning her back on the world in positive or negative narcissistic rejection of the ‘other’, other than in the abstract, is based on poems where far from describing the painting, Chang pulls out of it something that challenges the supposed ‘worldview’ everyone (perhaps even Agnes Martin at the level of her refinement out of the social world the concept of truly embodied desire. There is an insistence in this poem I love, which also speaks of Martin’s use of ‘lines’:

Agnes’s lines desire to touch each other, but never can. Depression is a group of parallel lines that want to touch, but never can. Or maybe it is a group of parallel lines that only other people hope will touch. …[12]

And what of her treatment of Agnes’s love of the use of boxes in rectangular or other form, and with them the idea of containment – the locking in of externalised meaning, even of language for a poet, who will always find language implies sociality as paint does not necessarily do so. Some poems speak of boxes such as the beautiful Summer, 1964, where named within it:

There are 1, 645 boxes. Inside each box is a small white dot. On some days the dot looks like a dot. On other days, each dot is one of my tears. 1, 645 tears in the last week.

Of course quantification boxes one in. The point is Chang asserts, in biological and metonymic truth that measures of number are not the key to comprehension any more than sentimentality, for: ’Tears do not come from the heart’.

They come from outside us like time, from one large repository. Which is why we cry when other people cry. In this way, tears are communal. We depend upon each other for our sadness.

This poem more than any other poem insists that the truth of obit or any other poetry about loss is not what lies deep inside the individual but in reaching out and grasping others – in the communality of our universal sorrows. But boxes act in other ways.

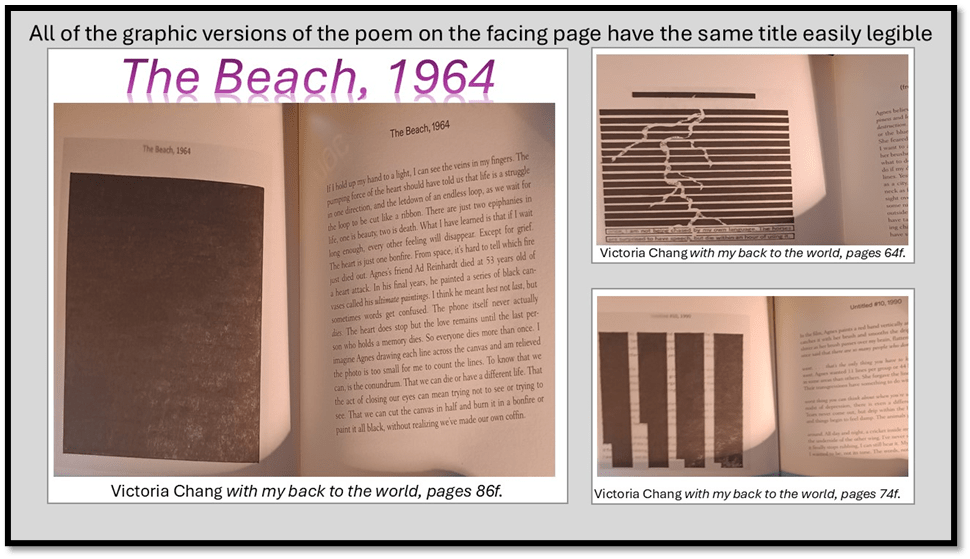

Many of the poems are accompanied by Martin-like forms of graphic which obliterate the poem’s words with a partial or full cover by a box or a number of boxes (in stripes sometimes) or of words that fight out of the box by changing the colour of their font. In Red Bird, 1964 [13] the bird is a metonymy of feelings about death that is ‘in a small box’ because burial has been thought unnecessary. No longer does the lyricist find ‘feeling’ contagious. Boxing a bird may mean it might as well be a rat the poem concludes, but even if a bird you would not through that black box to see a ‘red bird’, or, as I think it allows to think because of the metonymy enabling the use of the homophone connection in the word, a ‘read bird’. To read is to empathise if the poet / artist allows it. I think Martin and Chang allow it, though in Martin’s case the repressed lies more deeply buried. Martin doesn’t enclose her Red Bird (1964) in a ‘black box but in a cream-white box with a faint line of black dashes at its outside edges, laid on an identical white background.

Agnes Martin ‘Red Bird’ (1964) available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/34916

Boxed poems can contain the same suppression of data that contrast with expectations, largely those given by a title as Martin’s paintings do. The poems can, as I have suggested be covered by one box or many. They may not occlude all the words, which are all to be read on the facing page uses a regular printer’s font. For instance, in one box that covers only the typed lines presumed to be underneath it, we see some through the jagged gap made by a gap in the box shaped like a tri-forked lightning flash. The last two lines are not occluded by anything. Interesting effects occur here, which I will leave for other readers to discover and interpret.

In another lines show between boxes in the form of four boxes with the form of irregular shaped vertical stripes across the text, And in The Beach, 1964, a favoured poem by me a box covers the entire words but taunts us with visibility by being of variegated tone.

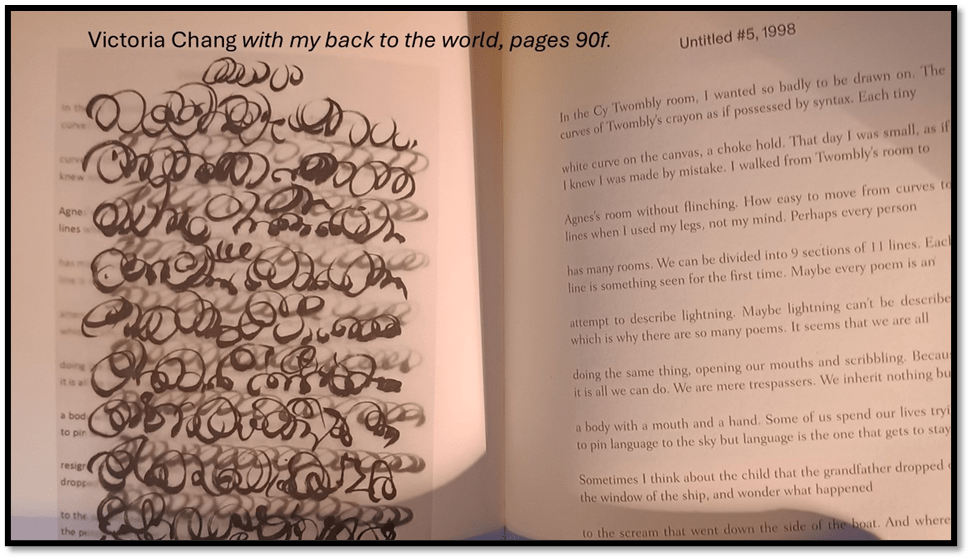

Sometimes text is obscured with other motifs. In a poem Untitled #5,1998 (which I said I would mention again earlier for other reasons too) that also invokes Cy Twombly, the marks which cover the page have a circular repetitive form that sometimes look like cursive script, as in Twombly’s work. The lyricist talks of her desire to ‘to be drawn on’, fully aware of the ambiguity of that in language – she wishes to be either obliterated or led forward. But she is aware of the violence that obliteration might involve since ‘ Each tiny / white curve (black in the picture – again a kind of play) on the canvas a choke hold’. It is my strong feeling that the key to the debate with Martin, and other artists, including Cy Twombly and Ad Reinhardt, lies in the fact that language is a deeply different medium to paint, even when Twombly paints language. Even though poets ’spend our lives trying / to pin language to the sky nut language is the one that gets to stay, for it can never be divorced from social communion.

And I promised I would mention a nuance with regard to this poem about mathematical calculation and basic counting of units. It is a rather different point to that I made above, as we look at the graphic version facing the text-only one of the poem. For Chang says of the Martin painting, and of her graphic poem I think: ‘We can be divided into 9 sections of 11 lines’.

The statement is literally true of Martin’s Untitled #5,1998 (see below):

But, literal soul that I am, I wanted to find it true of the graphic poem in the book. That does indeed have 9 sections (stanzas) but the number of cursive lines seems to only be 10, until of course, you see one partial line inserted to the right mid-way down the printed page. Even more nuance is added when you realise that this insertion also reads as a curved continuation of a line running diagonal (it is back to 9 and 11 as our number count then – and a reference to a famous catastrophe in global history in the USA). Yes! perhaps! But having noticed the diagonal, you perceive many more diagonals – possible lines proliferate and throw us into the danger of ‘miscalculation’ again. But, wait! Isn’t that the point. Miscalculation of an artwork or a poem’s measurement or measure might be the secret of the poem or artwork. Does the truth lie in the error. Such unanswered questions are the stuff of Chang’s wondrous art.[14]

Before I leave the use of boxed containment as a theme in the Agnes Martin poems in Section I and III of the volume (although we will return to it for its different use in section II), I think it worth hearing Chang talk about this theme to Seaborn in the interview referred to above. We may think boxes constraining as well as containing but sometimes they liberate text, as when the text turns white, seeming bright against a black box in Starlight, 1962.[15] Binaries do not help us, for the variations of liberation and constraint in any form are too multiple, as is femininity and masculinity, or black and white. This is what I understand Chang to have meant below in 2020. It is about Obit, and you will notice that in these new poems she does ‘give (herself) a box to write within’. At one time that box is her parent’s coffin. :

Oddly, the box form, the rectangular constraint, was really freeing. We think of form as oftentimes constraining us, but in this case, it was so free. I didn’t write in a box, like I didn’t actually give myself a box to write within, but I think that thinking in these terms, and this form that it was going to be in, was really freeing.[16]

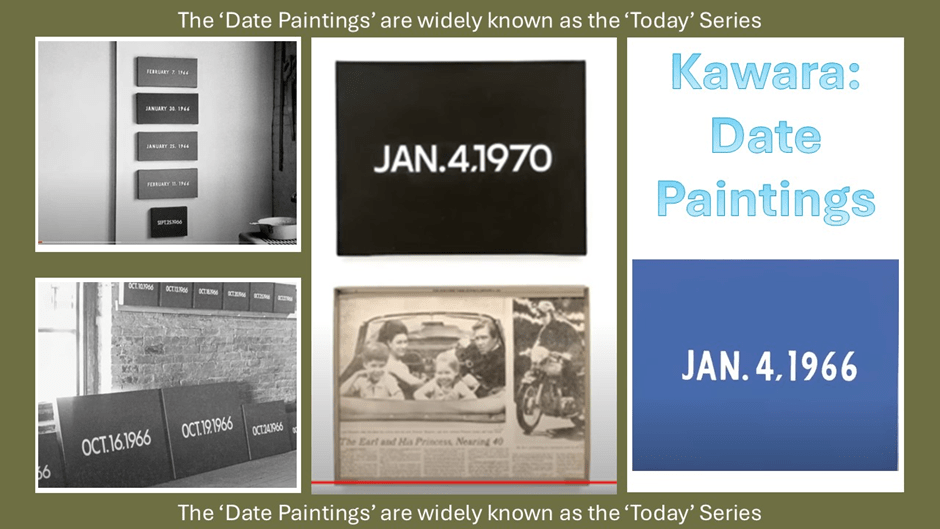

Burt before, for me sadly, leaving this volume I want to turn to the wonderful poems in Section 11, called Today and based on the Today series by a different artist, On Kawara. In fact Kawara knew them first as his ‘Date Paintings’ and he only used literal boxes to display them later in his career. Early on he needed to emphasise, despite the minimalist conceptualism of the mode of painting that he painted using several layers, that despite appearances on superficial look, whenever he used the ‘same’ colour background, repetitively and frequently, in fact the mix of the colour always differed as dis other features such as the precise visibility of dense brushstrokes. A good introduction to this work is provided by a very brief (less than 5 minutes) video from the Guggenheim Foundation by Jeffrey Weiss and colleagues. There is also at the website a transcript of the video commentaries and interviews. [17] An idea of the series appears in my collage below:

I think this poem though picks up on another aspect of the Today series which Jeffrey Weis and Kasper König talks about in Kawara when they discuss the effect of his addition to the paintings of containing box displays and one parallel boxed news-story from each day recorded. They say:

Jeffrey Weiss: After a certain date, Kawara began producing boxes for his Date Paintings and lining those boxes with newspaper clippings which were derived from the daily press.

Kasper König: So this is very Japanese. You know, you have a scroll painting, and you unroll it, and you roll it back, and you store it.

Jeffrey Weiss: The boxes originate with Kawara’s need for storage. He was living in a constrained loft studio, and he was producing an enormous amount of work in the mid-’60s. Each painting has its own box. And, of course, they contain the newspaper cutting. So each cutting from the newspaper represents a different news story of a given day. And when you line them all up, it creates some kind of a… almost the impression of a narrative. [18]

I think with these poems, as with the Martin ones, Chang wanted to both box up her record of the dying, death and mourning for her father, and to show how language presumes the presence of a felt voice. Her father’s death occurred after Obit was published, although he had been in a state of paralysis following stroke with no communication or mobility since before his wife’s death and hence, I think, the sense of retrospect in section II of this new volume. Of that ‘presence of a felt voice’ we need to add with Kathryn Savage that it, as in Obit, ‘externalises internal psychological and emotional states’ (including cognition I’d add) and, as Savage continuing puts it so beautifully: ‘What a gift to the reader, this invitation to press outwardly and inwardly at once as if both reaching and grasping simultaneously, as if holding hands’.[19]

But another feature of the Section II narrative is the different way it addresses concepts of counting and measure to the way it is done in the Martin poems with complex references to the measuring of time, distance and unit counts to show the difference between quantitative measure and the quality of feeling counting misses. The obvious example amongst the Martin poems is the poem that refers to the sexual abuse of Asian women because they all look alike to Western eyes it seems. The poem is Untitled IX, 1982. Here quantity fails to measure what it means to be ‘touched’, but the ambiguity of the word touch is deeply felt, for to be ‘touched’ is used too loosely in Western culture, but still hols deep potential for affect, as does this poems suppression of the events of racist rape lying behind it.

I counted 44 lines and while I counted 44 Asian women were touched. People confused the 44 Asian women with each other. How did Agnes know this was the colour of desire?[20]

In Today, count and measure refer us back to the poetic tradition, for each is a word to discuss the metre of poetry – a term that combines reference to both mathematics and music. These poems are in deeply traditional iambic pentameters (the line structure used by Shakespeare and Milton (to name but two), and you can count the ten syllables in each line. The form is loosely applied but diversions from the iambic foot structure always follows a need of emphasis in sound, meaning and feeling. But my subject is boxes, constraint and containment. Some poets have always complained that inherited metrical patters box in emotion, whilst other see it as liberating, but I hope to show liberating is Chang’s use of it, who felt as they thought and counted both syllables and stresses in here lines as she went. There is so much to love in this narrative elegy, for such it is surely, which pulls together themes of count, calculation and measurement by the clock with notions of the constructed and the boxed. But look at how these lines deal with emotion by metre. I will not comment much, just scan them.

Nów that /no-ońe /is léft,/ thére is/ nothíng léft to/ know. Th́ere /was név/er jóy /in lífe, ónly/ varý/ing leńgths/ of sád/néss, in betweén/ the cóws/, biŕds, and/ our lóok/ing úp.[21]

Largely this is regular, apart from the attempt to support the line structure of the verse with a stress on the first syllable of a line. Some inversions of the foot emphasise feeling (in ‘there is’, for instance, or emphasise the counting of animal forms, of which this poem has many, usually in iambs. What matters in these lines is the shift between the zero counts, emphasised by there contrast to ‘one’ to the quiet insistence on ‘our’ (quiet because relatively unstressed) in ‘our looking up’. There is emotional and narrative progression here.

But even more telling is the comparative use of parallels between conventionally printed text and text overlaid by graphic, usually black boxes used in documents to redact material as in the fictive example of a pro forma below where sensitive material is restricted.

Clearly redaction boxes censor material, and this may even be done when material is felt to trigger emotional responses we want to avoid. I will leave Section II, beautiful as it is, and as much as there is to say that I haven’t yet, with an example of this.

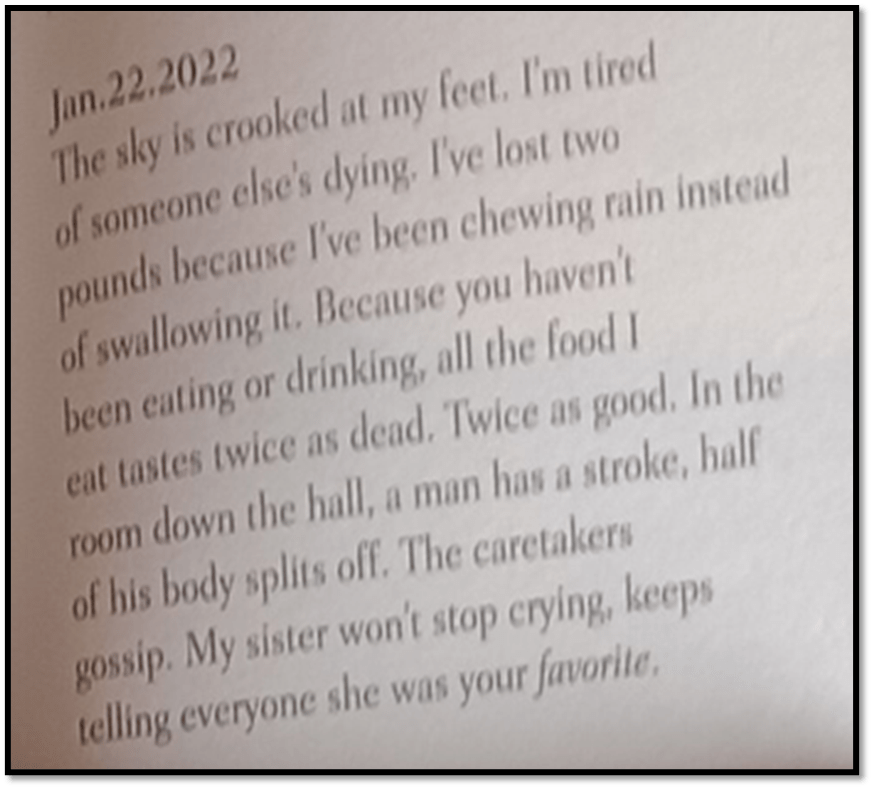

Most examples redact all the material but the date (in the fashion of Kurawa) in a current day in this poem but here (there is another instance, one word remains, the word ‘favorite’ (sic.). Possible interpretations of this abound and those are not my point. I just love the extra freedoms this gives readers to interpret, since they also know the underlying text which in this case faces the redaction. Here is the text, a little more legible.

The truths here tear at us. It looks again at the awful moments in mourning when we feel our empathy gone: ‘I’m tired of someone else’s dying’. Death becomes in such pain a stale taste, but a stale taste that the lyricist finds good The fate of another man, unnoticed by her sister, who has the stroke that had made her father to use the awful word ‘vegetative’ for so long occurs’ down the hall’. The content is overwhelming. Better this is redacted, perhaps, half the mind says. There are lots of inversions (or conversions of iambic into trochaic feet if you like) in the final lines, which mime the ‘weakness’ stroke brings for instance (/stróke, half), together with conscious raising of technical effects of alliteration, repetition and weak assonance, especially in the present participles. This, in itself feels like time itself gone ‘crooked’.

There is so much more that we could say of the handling of narrative and serial time and their interactions, which is crucial in this and other poems in the volume. Think of the narrator / lyricist wondering why ants congregate on her notebook on an epithet she’s written from Etel Adnan’s Time, who dies too through the course of the poem. In the approach to death time becomes material, and a thing to touch with the senses. The idea of touching time is the essence of the book, and see how the iambs assert themselves in this section, in order to beat time, or maybe more accurately tempo, so that it is like a heartbeat, which is how Wordsworth and Tennyson thought the iambic pentameter worked to engage us empathetically, according to A. S. Byatt. Consciousness about the use of the word ‘measure’ here is characteristic:

Jan, 27. 2022 When death was near, I could touch time. It was softer than I thought it would be. There were two of them. When I tried to measure their lengths, I was sent back to the living. I was shorter but the shadow was longer.

This, like other usages of the self-conscious reference to metre in the poem would be more clear if we remember that metrical analysis in English, for some at least although only because of the practice in Latin verse, prefers the analysis looking not at stress but the relative ‘length’ of sounds in a line: an iambic foot being a /short long/.

Heidi Seaborn got Chang to talk about ‘time’. She said:

The idea of time is always really interesting to me, too. How do you get outside of time? How can I not just stop time, but go outside of time? That’s what I feel when I read. If I’m in a mode of reading and thinking and quiet—and I have very little time to do that now, but I try and give myself that time, quiet, reading and thinking on my own—I genuinely feel like I’m outside of time. I think there’s that desire to not only stop time, but to get outside of it, and if it’s still moving and you’re outside of it, that feels really interesting to me. Because it feels like you’re asynchronous with the world and the earth and almost your own body. For me, reading is very spiritual. It’s a very out of body experience. That’s why I like to read, and that’s why I like to write, because it’s the only thing that feels like it’s not time-based, and it’s not moving forward. You’re in time, if that makes sense, or outside of time, but you’re not being dragged along with it.

….

What is time anyway? I don’t know. These are all bigger questions that are always so interesting to me.

The idea of being ‘outside’ rather than ‘inside’ time is a crucial one, as is the idea so like Aquinas’ idea of God of being the Unmoved moved Mover. But when Chang says ‘if it’s still moving and you’re outside of it’ she does not mean only time but the feeling of affect: EMOTION. The idea of empathy is, after all, based on holding time back enough to make it worthwhile to feel anything for anybody, even oneself considered as an entity. And the real philosophical point in today is this, again from the interview preceding the collection.

The process really taught me the ability to let go of things. Even though I loved something, I’d realize that not only does that word or phrase have to go, but the whole thing has to be changed. It was really a painful process, but I think I learned a lot about myself, and not to be so wedded to things

She is talking about writing OBIT here and letting go of favoured ways of self-expression for new discoveries. However, it is a resonant statement in Chang, who talks so much about death and loss and reactions thereto, She will never validate any one approach, maybe especially Martin’s, who she clearly respects as much or more than her mother, though that too is a nuanced thing, for her mother and father were perfectionists and they may have loved through the encouragement of aspiration rather than bonds of affection you feel when Chang talks about them, and why she HAD to grow beyond them and their influence. My final feeling as yet as I put this blog away and the book down which has been with me it seems, now I have grown to love it, forever is that to read is not just to enjoy exceptional poetry but to RELEARN what that thing is.

What I have learned from Chang, and perhaps other poets recently – like Frears and Joudah – is that Agnes gets it quite wrong, even about herself and her painting, in saying the ‘only thing you have to know – exactly what you want’. But Chang returns to her own case whose ‘error was to become what I wanted to be, not its tone’. To become the ‘tone’ of what you want to be is not a clear concept, neither is it to be the ‘cutting’ rather the words that define being. It is more than praise of the performative over the essential in the self. It is about reaching out to something you don’t know and may not know when it happens, unless you train your desire away from past forms.

This volume of poems is superlative. But it puts me in a quandary about seeing The Forward Prize awarded for a collection in October at Durham. The poets on the shortlist are all so different, each moving in different directions with poetry as a medium. Perhaps the best thing is let it happen and then let it go, and hope the ‘tone’ of beauty remains from reading all of these beautiful poets.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] From: Victoria Chang Leaves, 1966 in Victoria Chang (2024:39) With My Back To the World London, Corsair Poetry.

[2] Heidi Seaborn (2020) ‘A Conversation with Victoria Chang’ in The Adroit Journal (online) Available at: https://theadroitjournal.org/issue-thirty-one/victoria-chang-interview/

[3] Nicole Yurcaba (2024) ‘Poetry Review: Victoria Chang’s “With My Back to the World” –“What if I’ve spent my whole life wanting to be seen?”’ in Arts Fuse (online) [April 2, 2024] Available at: https://artsfuse.org/289195/poetry-review-victoria-changs-with-my-back-to-the-world-what-if-ive-spent-my-whole-life-wanting-to-be-seen/

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnes_Martin

[5] Kathryn Savage, op.cit.

[6] Nicole Yurcaba (2024) ‘Poetry Review: Victoria Chang’s “With My Back to the World” –“What if I’ve spent my whole life wanting to be seen?”’ in Arts Fuse (online) [April 2, 2024] Available at: https://artsfuse.org/289195/poetry-review-victoria-changs-with-my-back-to-the-world-what-if-ive-spent-my-whole-life-wanting-to-be-seen/

[7] Victoria Chank 2024: 39

[8] See ibid:37, 23

[9] MoMA (Accessed 2024) ‘Agnes Martin. With My Back to the World. 1997’ MoMA website. This page available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79892#:~:text=These%20six%20paintings%20form%20a,have%20her%20works%20displayed%20alone

[10] For the queer connection: ‘She moved to New York City in 1957 and lived in a loft in Coenties Slip in lower Manhattan.[7]: 238 The Coenties Slip was also home to several other artists and their studios.[5] There was a strong sense of community although each had their own practices and artistic temperaments. The Coenties Slip was also a haven for the queer community in the 1960s. It is speculated that Martin was romantically involved with the artist Lenore Tawney (1907–2007) during this time.[5][12] A pioneer of her time, Martin never publicly expressed her sexuality, but has been described as a “closeted homosexual.”[13] The 2018 biography Agnes Martin: Pioneer, Painter, Icon describes several romantic relationships between Martin and other women, including the dealer Betty Parsons’. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agnes_Martin).

[11] Chang ‘With My Back To The World, 1997’ in Victoria Chang, op.cit: 3.

[12] Untitled, 1961 in ibid: 24

[13] Red Bird, 1964 in ibid: 69

[14] See ibid: 90f.

[15] Ibid: 16

[16] Seaborn, op.cit.

[17] Jeffrey Weiss et. al. (2015) ‘On Kawara: Date Paintings’ video from the Guggenheim Museum [online] (4:43February 6, 2015) Available at: https://www.guggenheim.org/video/on-kawara-date-paintings

[18] Ibid. My emphasis

[19] Kathryn Savage, op.cit.

[20] Victoria Chang, op.cit: 31

[21] Feb. 7th in ibid: 56

3 thoughts on “Agnes must have miscalculated’: The math that we get wrong in art, perhaps deliberately. This is a blog on Victoria Chang (2024) ‘With My Back To the World’”