A writer at Work: A quick look at Derek Owusu’s novel in preparation possibly entitled Kweku. Submitted with trepidation (but with no request for answer) to @DerekVsOwusu

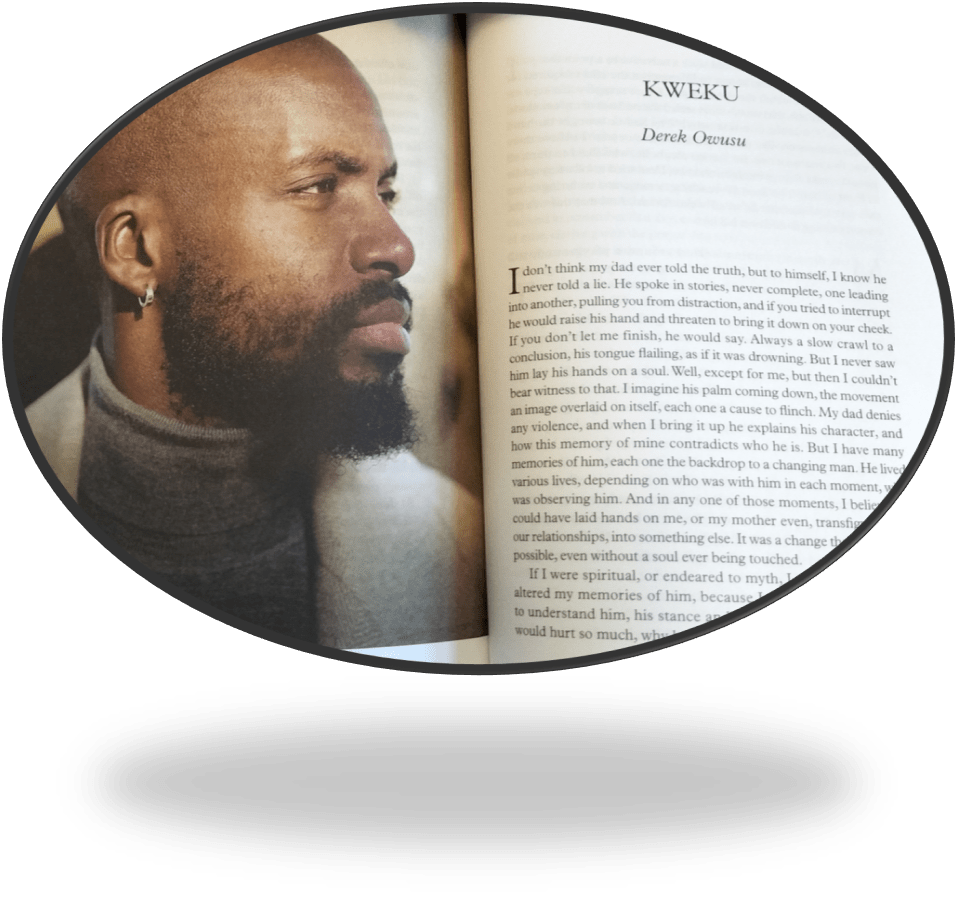

In a recent diary piece on a stay at the Edinburgh Festival, I included the following, about which I am ashamed enough to come clean, for I have just read his piece from the Spring 2023 Granta (Issue 163): it’s title Kweku. The piece below is somewhat edited.

The next event was based on the recent edition of Granta magazine which contained stories or early studies for new material from people considered the best of British young writing (40 being the cut-off date for ‘young’). But to be truthful, I was only attending because of my interest in Derek Owusu, whose light ought to be shining more brilliantly over the whole literary scene.

And seeing Owusu was worth it. However, in such an event there was not much chance other than to just see him, although, since Derek is extremely good looking, maybe seeing him has its own benefits. For that reason I have little enough to say. Other attendees kept talking about what a stimulating event it was in their questions but to me it felt rather bitty and without much force as a means of consolidating what it means to know a writer. Thus even my admission of liking the look of Owusu feels like bad form because I know him mainly as an innovative writer about and within ways of understanding mental distress and an outstanding one at that, whose books could change things and also of someone who recognises the dangers of the eroticisation of young Black men in white queer culture. I was pleased to say to him that a modern writer who entitled one of his books Safe and another one Faith, there was certain to be something entirely world-changing in such reversions to concepts usually guarded by the battalions of the political right and the champions of all kinds of normative response to the world. He is definitively NOT one of the latter. He will surely make greater waves than we are yet aware of in literature and in accounts of mental health experience. I hope so for he writes like NO-ONE else I know.

My only excuse for writing so slavishly about this guy and focusing on his compelling visual attractiveness is that I was possibly already at that time in that tired and enervated state of mind that could have been the bout of Covid I have now. It’s a poor enough excuse and I offer unreserved apologies to the writer who deserves better than to be the subject of such superficial and unrequested attention.

Reading the Kweku piece which addresses the experience of both himself and his father indirectly no doubt, as Losing the Plot (my blog on this can be found at this link) does with the experiences of both himself and his mother. Owusu pointed out at this session that it is mistaken, and perhaps presumptuous, to conflate him as a novelist with the identity of the fictional character who ‘writes’ the marginalia supposedly to the third person account of his fictional mother in the novel. They intersect he says for Owusu’s own mother had some of the same experiences as the mother in the novel. However, nothing in the novel tells us where the line of fiction and the fact of his own mother’s experience overlap, for how, with such a subject – the unusual beliefs and experiences created by extreme trauma and which some label psychosis. The same acts of disguise will inevitably be in play in the new novel, though the method looks as though it may be entirely different, in relation to the treatment of another son, who was to fall foul of alcohol at his father’s death, an alcoholic, from alcohol related liver disease. These circumstances cannot be treated as the ‘facts’ of either his or father’s experience.

For me the piece had another attraction. I think of Owusu as using the experience of mental distress and response to trauma to queer our normative expectations of the world and how we see the stories in it and their meeting points. But I do not see him as addressing LGBTQ+ themes as such. Yet Kweku does cross this boundary of normative expectation too. Again no assumption can be made that this is a ‘coming out’ novel for Derek Owusu himself. It is like him to respect all diversities and their intersection – his edited collection of essays, Safe, does precisely this with other writers giving material on the experience of Black queer young men (find my blog on that collection at this link). But the piece Kweku, ends with a son, acting as narrator, taking alcohol for the first time at the death of his alcoholic father. That son and Dad are drawn in a liminal space between any rigid sense of their distinct identities is very clear.

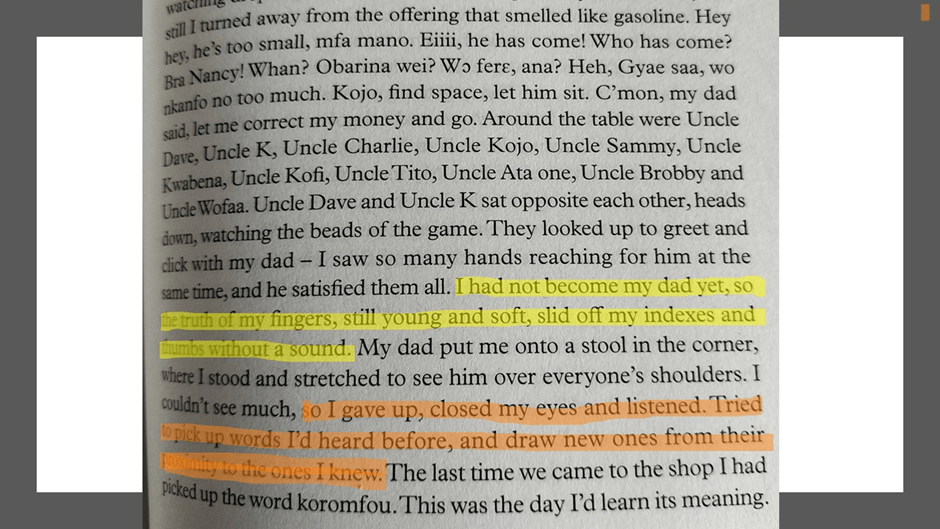

Before the scene in which he takes his first drink the narrator remembers going into Ghanaian owned shop in Tottenham Court Road. But this functions to show that Owusu’s narrator feels unclear about the boundaries within the liminal and hence mixed loci of consciousnesses within which it is necessary to write at the same time: These are at the least the consciousness of the child-self depicted and that of the narrator of the child-self from his current adult perspective, to say nothing of possible future ones (for are not most men at most ages beings that have not ‘become my dad yet’). And there are other issues. Are these liminal points of view of events mediated too by the consciousness of both child and narrator of how he is seen by his father’s friends who by virtue of being friends have also become his Uncles (a father’s male friends would become Uncles without need of other familial bonds – true of many cultures – even white working-class ones once – in my memory of these). How are we to read this beautiful sentence?

I had not become my dad yet, so the truth of my fingers, still young and soft, slid off my indexes and thumbs without a sound.[1]

The issues of understanding here are of course those associated with poetry, and of an embodied knowledge, where the names of the body parts still bear something excess of their cognitive content, something of sensation, whilst leaning out to other future cognitive functions, such as those that connect the function of an index finger to indexes through which a books referents can be listed. It is beautiful. It is difficult to see other writers daring this in the way Owusu does. And these issues are deeply locked in specific and perhaps localised cultures – even localised to different London districts or churches or even idiolects established by powerful people in their own community. Owusu’s narrator will claim soon that:

We’re raised in what would be a body of lies to someone else, truths expressed in a language that sings false to those of a different church, different culture.[2]

By the way, before I make my main point here look at the wonderful phrase ‘sings false’, it works mainly in attaining beauty because it activates memory of the phrase ‘rings false’ (a dead metaphor that has become a hackneyed phrase – no one thinks of the sound of an unspoiled bell – and therefore ‘true’ because cracked bells do not ring true – now when they say the phrase). It lives again in ‘sings false’ because of that assonantal resonance between the phrases and the difference in the music used to be a metaphor for truth being proclaimed. Only fine writers do that. However, that idea of a ‘body’ of lies in this sentence is central to understanding not only language but also Owusu’s exciting notion that lies and myth AND language (they become interchangeable in the narrator’s discourse sometimes) are embodied – not only in each person’s individual body but the body of the embodied community – of Uncles or others. The simplest form of that can be seen in the episode to which I refer. When men become related as uncles purely by a matter of naming, language clearly is more than a mere sign of body relation. In the passage in the shop, the language in conversation appears hybrid between English and a language I can’t identify.

Of course the likelihood is that it is a Ghanaian language but not only do I not know that for a fact but Owusu clearly wants to show that he, as a young child, is only beginning to learn this language in which his father excels himself by trial and error, uninstructed in any formal way by his fathers and the Uncles. Unable to see what is going on, he attends by listening, trying ‘to pick up words I heard before, and draw new ones from their proximity to the ones I knew’.[3] Understanding this linguistic exchange is not the purpose of this passage, rather understanding the universality of the problems unfamiliar languages, or aspects or localised forms of a language (and these could be unfamiliar for any number of reasons) that faces all novices, and in some arenas we must all be novices. And the burden of this story is how one inherits the Name of the Father (as Lacan called it), the language in which fathers are ontologically difficult to separate from lies and myths, the stories they tell themselves and each other. Indeed ontology yields to epistemology as the central problem of metaphysics in a storied world. Take for instance these two perceptions of the world lying some distance from each other in the extract:

I don’t think my dad ever told the truth, but to himself, I know he never told a lie. He spke in stories, never complete, one leading into another, ….

…

To maintain a story, many will alter ideas and truths, motifs and threads. We contort our tongues and tailor our thoughts, rehearse our lines to reshape the world in the image of our narrative.[4]

But though clearly Kweku is a story in which we are to begin to understand the meaning of ‘alcoholism’ in the complex network of behaviours and metamorphoses of form that constitute human being, it is obscured by a necessary truth: ‘A story, like deceit, or myth, is never finished. Each retelling or recalling is embellished by what came before, adorned by what could come after, fortified within the present iteration’.[5] How clever Owusu is about the nature of the mind-brain continuum and, let’s face it, about embodied life in general, wherein language is but yet another excretion of the body, still believed to be of the body but bruiting its independence, as according to psychodynamic thinkers, its own turd does to a child, making it an ideal gift of itself to its parents.

But the language game I most enjoy in this intrigues me more – and probes feelings I have long had about the source of Owusu’s queerness as a writer. He has to now never made his theme about sex/gender queering of his themes, though his book Safe allowed other young black men to do so. One of these recently wrote a brilliant book, about which I have blogged previously which takes the concatenation of father-son-male lover triangle into the realm of the deeply and metaphysically queer. The blog is linked here: and I refer to Okechukwu Nzelu’s (2022) Here Again Now.[6]Nothing of this extended kind of meditation on masculinity is even promised even in the Kweku extract although who knows about the novel to come. The end of the story though exploits the now totally open game for sexual and/or human-relational thinking based on the word ‘partner’: one forced on queer people as the only alternative to what heterosexuals claimed to themselves as ‘marriage’ (or the state / region / convention claimed for them – for truly they were not agents of this in themselves), this became solidified in law in the form of ‘civil partnership’ until marriage became an option for those wishing to live in exclusive single-sex couples.

At the end of this story, drunk in a bar, the narrator waits ‘for someone to pick me up’. The vagueness of someone when complicated by ‘pick me up’ veers between the language of the genesis of a one night stand, without not also being the name of waiting for another to come for you, The writing of this passage is incomplete like Dad’s stories – is the ‘partner’, clearly identified as male, named some lines later, a partner of the narrator who had been waiting for his partner, the narrator, at home, a one-off ‘pick-up’, a partner for one night in all likelihood, with perhaps mutual complaints the next day that they were so drunk last night (‘sorry’ – I don’t usually do this!). Another possibility opens up however from the vagueness of reference, the ‘he’ who ‘squeezed me’ as the narrator lays his head on the bar: ‘someone’s head, a bald patch, a collar, the tiny bumps on someone else’s neck, te back of another body’, is the father the narrator has just lost but always wanted – the gentle male body who comforts one through the touching of each other’s body – the proximity where you ‘taste the perfume coming off his chest’.[7]

And that man anyway is as near as damn it too a spider you can drown in the bath: ‘Bar Nancy’, Kweku Anansi, the mythical spider with whom Kweku identifies whom a son might yet threaten to kill.[8]

All my love

Steve

[1] Derek Owusu (2023: 203) Kweku in Sigrid Rausing Granta (Issue 163: Spring 2023), 199 – 206.

[2] Ibid: 204

[3] Ibid: 203

[4] Ibid: 199 – 201.

[5] Ibid: 202

[6] Okechukwu Nzelu (2022) Here Again Now London, Dialogue Books

[7] Derek Owusu op.cit: 206

[8] Ibid: 203, 200 respectively

3 thoughts on “A writer at Work: A quick look at Derek Owusu’s novel in preparation possibly entitled Kweku. Submitted with trepidation (but with no request for answer) to @DerekVsOwusu”