Fated to love, or fated to die – this blog is a review of ‘Fireworks’ by director, and the use of the history of homophobic hate and queer redemption in the Giarre murders and its aftermath in the history of Sicilian Gay Liberation movement.

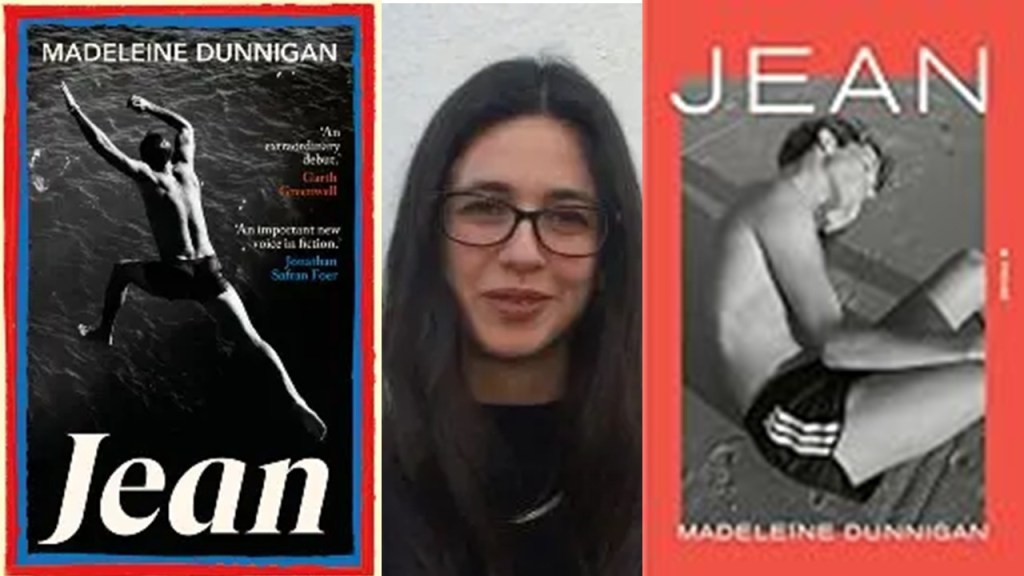

I am currently reading an amazing and beautiful novel about how love arises and gets between teenage boys called Jean by Madeleine Dunnigan . I will most certainly blog on this brilliantly written and plotted novel but it struck me that in its central scenes in the public school Jean attends, there is a fantasy party celebrating the school where, organised by headmaster David and the humanities master Charles, most of the teachers and boys drag up to celebrate coming of age and to tittilate the girls invited to the party from a neighbouring single-sex school.

The initiates – the boys leaving school for the adult world including Jean take on allegoric roles.Jean is allocated the role of ‘Perthro, which Charles says, pausing for dramatic effect, means destiny‘. [1] Only afterwards does Jean realise that Charles had invented that association, just as his love for Tom becomes consummated in his mind, that the word means literally ‘Nothing’: The chapter ends: ‘i am nothing. i am nothing’.[2] About all this I will perhaps talk about when I have finished the novel and write the blog, but already it has made me think about the particular necessity of ideas of fate and destiny in the lives of marginalised queer people in the later twentieth century – my period as it were. And these thoughts have been consolidated temporarily around the fact tat Geoff and I watched the beautiful Sicilian set 2023 film Fireworks ( Stranizza d’Amuri) by Guisseppe Fiorelli last night on DVD.

Fireworks is based on events that are very roughly indeed based on a real murder known as the Giarre murders in Catania, referred to in the article below, in Italian.

The facts of the case are briefly summarised in Wikipedia:

On 31 October 1980, the decomposed bodies of two young males, 25-year-old Giorgio Agatino Giammona and 15-year-old Antonio “Toni” Galatola, who had disappeared from home two weeks earlier, were found dead, hand in hand, both shot in the head. The two boys were called “i ziti” (‘the boyfriends’) in the village. Giorgio in particular was openly gay, after having been caught at age 16 in a car by a local carabiniere with another young man. He was denounced and given the Sicilian derogatory nicknam”puppu ‘ccô bullu” (“licensed homosexual”).

The film is set in tbe Syracuse region of Italy and exploits its historic associations through its quarried landscapes rather than Catania further in the North, rather than South, East of Sicily and in 1982 as a further open disguise. Fireworks does not use the real names of the murdered young men, changes their respective ages and heavily romanticises the context of the relationship, not least in the use of fireworks as a title, plot element and symbol both of the short and long-term consequences of their relationship and the relationships in their family networks. It uses prominently the graffito “puppu ‘ccô bullu” (“licensed homosexual”, though translated in the subtitles ‘certified homosexual’).

It is without a doubt, despite the cleverly crafted felt dramatic tensions of the fact of seeking same sex love in a rabidly homophobic and toxic masculine culture (Geoff kept shouting at the screen” don’t kiss him in that public place”), romanticised and rendered beautiful in every respect that perhaps transforms any recognition of the gritty and ‘real’. It does however do so in ways that evoke the role of perceived destiny or fate, that same narrative and person-centred double teleology in the archetypal romantic love story, be it Romeo and Juliet, or Tristan and Isolde.

What is the double teleology you might ask of romantic love? It is that aspect of romantic tragedy, the only true romantic genre sin e the middle ages, that predicts a necessary ending for a couple of ‘star-crossed lovers’ wherein the mutual affirmation of love and mutual death are both expected and fulfilling consummated images of each other. In the case of this film, although as in Greek tragedy, most viewer would have known at least a mythicised version of the ‘true atory’ it was based upon, both endings seem.pressing on the viewer continually. In the still below for instance, from left to right, Samuele Segreto playing Gianni Accordino, and Gabriele Pizzurro playing Nino Scalia talk of how, though they have just witnessed physically the hatred and violence directed at both of the village in which Gianni lives, and indeed of their parents, they will ‘make it work’, by which they mean the culmination of their love story, even if it must be in secret.

However, it is in on the beach of the river below that bridge that both will be heard, though unseen, to be killed by two immediately consecutive bullets from a gun. Guns are only one of the explosive devices that run through this film and most of Nino’s family in particular have a close and ambivalent relationship with hunting, though usually rabbits, with guns, even Nino’s little nephew, Totò played by Simone Raffaele Cordiano whose mastery of enacting infantile jealousy is amazing [in the true case the nephew was the murdered although at 13 he could not be charged under Italian law].

Of course, no queer viewer will fail to be enchanted by the beautiful innocence of the portrayal of these boy’s love for each but so much of this film is about the complexity of queer families and the ambivalence of supposedly homonormative communities. For instance, Nino’s uncle Ciccio Scalia (Giuseppe Spata, shown rather windblown but bare-chested in the photograph below outside his caravan with Nino) confides to Nino at his lowest that, from his experience (for he too loves men) ‘things can last forever if done secretly’.

It is tragic advice for Nino for his secret love is now public knowledge and cannot be hidden even by overt lies, but it exemplifies that heteronrmativity is actually an appearance easily fractured in practice and covert knowledge of that practice.

That truth is apparent too in Gianni’s life. Having already been sent to a reformatory for having oral sex with a co-minor, he is the butt of communal jokes and cruel practices. Often led by Emmanuele (played by the Giuseppe Lo Piccolo), the man who thinks himself the top cat of the bar and saloon next to Gianni’s home, and who turns the longing for notoriety into evil, constantly find ways of humiliating Gianni and his mother, Lina’s, lover, Franco who has a garage across from the bar, where he employs Gianni. At one time Emmanuele daubs lipstick on Gianni’s lips, without the latter’s consent and to his cost in terms of how his male peers see him.

As the humiliation turns nearer to physical violence against Gianni, he is saved by Turi, played by Alessio Simonetti, whose sexual ambivalence means he is attracted sexually to Gianni, and to his ambiguous credit, will sometimes save him from Emmanuele. However, Turi believes his sexual advances have been turned down by Gianni, although in fact Gianni genuinely has a task to be completed for Franco, delivering a moped to a home a long distance away. Spurned, Turi immediately turns from gentle seduction ( with rape too obviously a possibility) to antagonism and he picks up Emmanuele on his scooter, to chase Gianni, for so.e violent purpose wherein rape supposedly used as punishment of Gianni by both of the older guys might still happen:

In the still above, with beautiful Sicilian coastal landscapes behind the, the men harass Gianni, endangering him to a fall and in the end leading to an accidental collision with Nino Scalia on a spin on his new birthday moped from his parents. The sexual ambivalence of supposedly heteronormativity is then always uppermost in this community, as Ciccio’s role shows it is in the Scalia family, however macho it’s appearance.

Parental affection comes in for special treatment as part of the tragedy of the story as it speeds, if no faster than a moped through beautiful landscapes. Simona Malato as Lina, Gianni’s mother plays brilliantly a mother torn between love of her son, that has Oedipal elements at first apparently on both sides, but who is also jealous of losing her son – to anyone, but that he is a ‘certified homosexual’ gives her an excuse to save other boys from what she convinces other mothers, Nino’s in particular, from his predation. She sounds evil but what comes out of Malato’s embodiment is so.ethi g nuanced and tragic about women in patriarchal society. Her eyes leak both pain and abandonment, which while no excuse for her possessive hold on Gianni certainly show its determinations as complex.

Antonio De Matteo as Alfredo Scalia, Nino’s father, and craftsman in fireworks entertainment and shows is equally strong ina role that shows why we should never talk of ‘toxic masculinity’ as if it were not a construct of patriarchal societies but a function of biological sex/gender or of individual male personalities.

The relationship between Alfredo and his son is beautifully developed through Alfredo’s decline into bronchi-pneumatic illness and in reading fragility imposed by the condition, and his refusal to stop smoking. Having taught his son all he knows of designing g and creating beautiful and semantically targeted fireworks events,he recognises his son as ‘an artist’ of the trade and gives over responsibility to him, who has now brought Gianni in to assist him and learn the craft.

Alfredo hands over responsibility at an al-fresco dinner in front of his home, recognising that Gianni is a worthy apprentice and growing craftsman, although Gianni has somewhat reconfigured his family history to charm Alfredo and his wife, Carmela, played by Fabrizia Sacchi. It is easy to underpraise Sacchi, for the role of Carmwla, unlike Lina, is simpler but no less based in tragedy. I laboured to find a still of her before I realised that her contribution was often that of an observer, but a complex one. Witness the still below where the camera’s eye-view is that of Carmela from within the kitchen, the place we most often see her serving sumptuous meals to Alfredo’s extended family.

The boys hear Nino’s father delivering an encomium to each of them with pride and love of Alfredo in their eyes. For Gianni at this time we see Alfredo morphing into a substitute father for the one he never had, despite telling Alfredo he had such a father now in Germany and that he loved him. But the vision is blurred by glass (and perhaps Carmela’s tears)and criss-crossed by the grid of the window leading, creating the sense of the imprisoned vision of Carmela. It is to Carmela that village gossips have run to inform her that her son has been seen kissing the ‘certified homosexual’ Gianni, and it is Carmela Lina calls by telephone to warn her that her son may be ‘corrupted’ by Gianni.

Carmela’s emotions are friable. Seeing the boys with her husband,she throws the dinner plates on the floor. When her son runs in to help her she talks in code about not doing things one ought not to do, like dropping plates, and to be careful, for she dare not voice her fears and lose him.

If Sicily provides the both beautiful green and grimly dry landscapes, where rabbits are killed (and boys trained to kill them) by Alfredo’s brother, the quarry owner, then the night shots are beautified by the Scalia family’s fireworks displays. Fireworks are often a stock symbol of consummated sexual love, and though one scene predicts that for the boys as they become master fireworks craftspeople, put it next to the scene where fireworks show the passions of the divide between Alfredo and Nino when he comes separate him from Gianni, we see that’fireworks’ can use their beauty too to show the explosive beauty unfamiliar divisions and of the unresolved.

But the fireworks are very much like the double teleology of ro.anric tragedy that makes death the true sexual and romantic consummation of both Romeo and Juliet and Tristan and Isolde. It is the explosive gunpowder bang of the two shots, to whose consequences the film literally blinds us that consummates the love of the two boys, after underwater scenes of their close touch of each other, and their loving proximity on the secreted beach.

But the beauty of such love is not really about consum.ation but in all the travelling done together in which their proximity grows, on the moped Alfredo and Carmela gifted Nino. Those scenes haunt you after seeing the film and will draw me back to it

And most of all I think I value the scenes in which Gianni after treatment, presented as supportive and therapeutic, that civil society, communities and families pile on forms of love considered abnormal, is in the beautiful gaze of Gianni in which all of a sudden and repeatedly sees his destiny as redemptive of queer love, except that we always know that this confident gaze will bow to personal tragedy.

The film tries to convince everyone us that though the boys are killed, and their tormentor and killers, including the carabineri in some accounts, got away without punishment, the gay movement that sprang from that was in itself a redemption. I doubt that as the tables turn on queer communities again.

Do get the DVD or stream.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

_______________________________________

[1] Madeleine Dunnigan (2026: 126) Jean London, Daunt Books

[2] ibid: 141.