A week of Hamlets: [2] From some perspectives ‘Hamlet’ is a play about taking responsibility for your country.

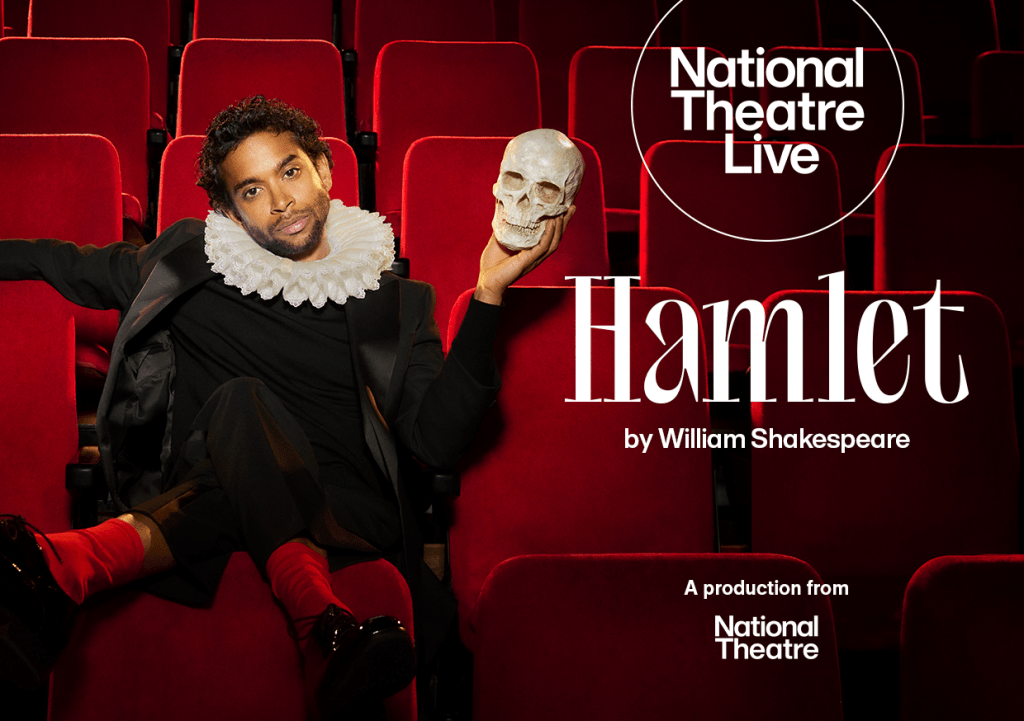

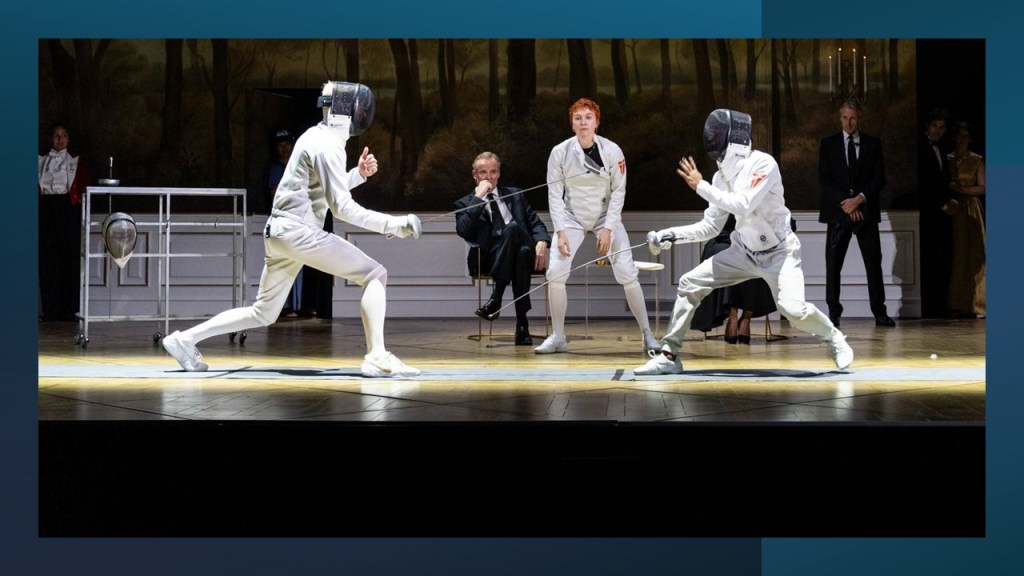

Part 1 of this blog can be found at this link. Yesterday Geoff and I saw, after its first launch, the streamed version of the National Theatre’s most recent Hamlet from the Lyttleton Theatre. The choice of theatre was significant, for the alienation effects in this production, those effects that remind us that what we are seeing is in fact an artifice, a performed construction of life rather than an imitation of it. The play within a play sections work precisely because they stress the artifice of the era of the proscenium stage from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. Lyttleton is a proscenium stage theatre unlike the Olivier. The flavour of the production is a stress on anachronism and lack of socio-cultural consistency – people in it dress with fragments from different times and places, except when in performative style in fencing costume, which seems evoked throughout – even part of Ophelia’s mad scene is played in a fencing visor and carrying a fencing sword, properly bated for play, unlike that of Laertes which kills Hamlet. Ophelia mad plays between the roles she has been given as a repertoire: such as passive-active, and angel-whore.

Unlike Riz Ahmed’s film Hamlet, this production has few obvious cuts, including even the long speeches of the players about the death of Priam that Hamlet calls for, only to find in it the passion for the defence of nationhood that he does not possess, a thing constant through the play making for the most telling comparison in that with Young Fortinbras, the son of Old Fortinbras of Norway, defeated in battle by Old king Hamlet of Denmark with the gain of some marginal lands. It does not cut either the essential background story of the relations between the states of Denmark and Norway (with some issues about Poland also considered) . The story is told in the first Ghost scene by Horatio but often cut, as too complex, from which comes this:

Now, sir, young Fortinbras,

Of unimprovèd mettle hot and full,

Hath in the skirts of Norway here and there

Sharked up a list of lawless resolutes

For food and diet to some enterprise

That hath a stomach in ’t; which is no other

(As it doth well appear unto our state)

But to recover of us, by strong hand

And terms compulsatory, those foresaid lands

So by his father lost.

Act 1, Scene 1, 108ff.

Young Fortinbras’ passion for the redemption of lands lost by his Father leads not to Young Prince Hamlet taking on his martial enmity to the Fortinbras Norwegian dynasty but to the election of Young Fortinbras to the leadership of Denmark on his rapidly coming death:. It is this very circumstance that feeds the characterisation of the enemies of the Elsinore land investment firm, Elsinore, by the dispossessed by that firm in the Riz Ahmed film. It reinforces that in both cases, whom passes as ‘lawless resolutes’ and who as ‘freedom fighters’ depends very much on the circumstances of your political perspective. In The National theatre this time much of the full text is used if paced at breakneck speed But restore the full text and many issues arise. Fortinbras is difficult to make into a pleasing hero. And whereas in productions I saw in the distant past made Denmark under King Claudius a kind of fascist state (on the strength of Hamlet saying “Denmark’s a prison” to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, this production tends to see Fortinbras’ crew as the willing beginnings of at least a military state to replace the vapid one of many combined cultures and no consistency that might be called ‘Danish’ which appears to be that state as run by Claudius, with his pro-European mainland style and general ‘freedom of movement’.

Hamlet, at the end becomes the harbinger of that military state, though he has seen it make its way into Danish life by sleights of hand, lies and threatened violence. He dies electing Fortinbras’ crew as his choice for power.

O, I die, Horatio!

The potent poison quite o’ercrows my spirit.

I cannot live to hear the news from England.

But I do prophesy th’ election lights

On Fortinbras; he has my dying voice.

So tell him, with th’ occurrents, more and less,

Which have solicited—the rest is silence.

Act V, Scene 2, 389ff.

It grates on some that Hamlet ends with the young Prince discussing international affairs – the payment of dues to England for the murder of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern and the settling of claims with Norway. Hamlet goes the whole hog, not only restoring the lands won by his father to Norway but enabling Norwegian rule over the kingdom he never ruled but in possible future promise. He instructs Horatio to reduce the story of the play to these political events (‘th’ occurrents, more or less’) and ensure ‘the rest is silence’. In Hamnet, this speech is turned into evidence of Shakespeare’s love for his dead son, proving the same to his wife who had never understood the poet’s vocation – the ‘rest is silence’ is heavily romanticised rather than showing, as it sounds, as a bit of too late political interest in the fate of Hamlet’s country by suppressing the story of a family’s ‘tragedy’ of extinction.

Fortinbras in this production is a brilliant portrayed kind of meathead military opportunist (I saw him as a kind of Farage), who pretends to take with sorrow what, in fact the audience know, he has always desired but never thought he would win so easily. But he soon invents, as was the way with rebels (compare Henry IV Bolingbroke as Henry VII Tudor) , some far-fetched (in the true meaning of the word since about seeking evidence from long-past marriage alliances) rights to be king in Denmark.

For me, with sorrow I embrace my fortune.

I have some rights of memory in this kingdom,

Which now to claim my vantage doth invite me.

Act V, Scene 2, 431ff.

What we note in this production is that Denmark is a confusing and contradictory hotch-potch undifferentiated and un-boundaried culture anyway (even though it opens with a watch set to subject any movement by Fortinbras, its a pretty ineffective one with plenty of time for gossip and ghost-watching. As I have suggested already it lives through the freedom of movement of its wealthy citizens and foreign cultures: sending its sons abroad (Paris for Laertes, Wittenberg for Hamlet, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern) for education or politically convenient death or absence (why Hamlet is sent to England). No doubt those sons, when they survived made the country they returned to a mix of cultural practices (the passion for court-fencing probably from France) including attire.

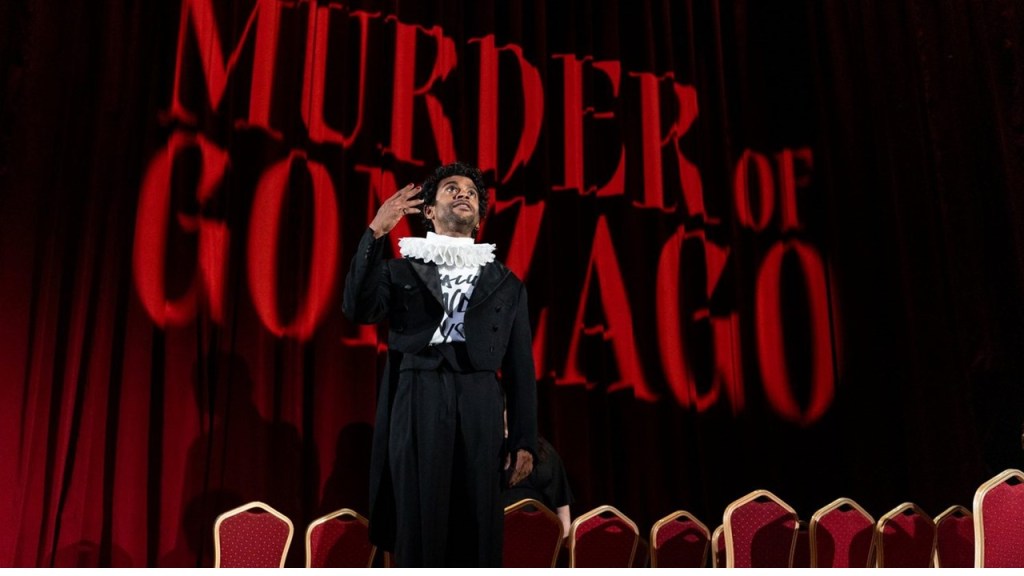

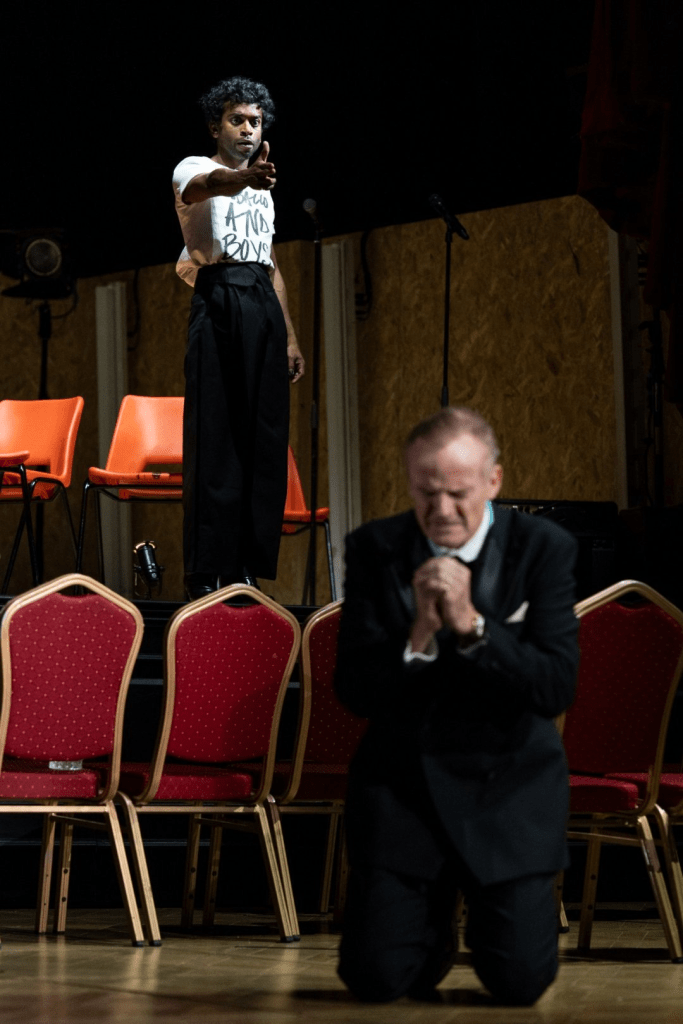

Hence our Hamlet wears modern red ankle socks, an old Blockbusters (a now dead company in present day UK even but I remember it) video t-shirt, but also later an Elizabethan ruff (strange anachronisms) as well as a fashionable (twentieth century wise) black suit donned for state parties. At other times he wears a woolly hat and puffer jacket. Above the mixed attire of him with Wittenberg Danish friends and peers Rosencrantz and Guildenstern have the loose flexibilities of upper-class public school culture that cuts through and confuses class and other distinctions. Their homosocial culture is also a kind of homo-affectionate one (in some speeches even homoerotic – where Hamlet searches through their clothese whilst they sleep).When he loses the Blockbusters T-shirt, he adopts a white one emblazoned with a black-charactered legend reading ‘Tobacco and Boys‘. Even when in formal wear, there is cultural variation passing by unmarked to general notice such as where Hamlet in formal Western black suit wears what appears to be an angavastra (Sanskrit: अङ्गवस्त्रम्) to mark respect for his father’s death months after the event and when he is told he should be celebrating his mother’s re-marriage.

The reference is a supposed statement, collected in records made by spies and used to incriminate him before his own patron spymaster by Christopher Marlowe, a young queer rival of the young Shakespeare (see the blog on a recent play at this link): ‘All they who love not tobacco and boys are fools’. The reference will be recherché for many but is of a piece with the cultural incoherence of this production – a modern t-shirt with an ‘old’ legend of rather risky meaning, since an invocation to pleasures seen as ‘niche’. Some aspects of this reflect a kind of artic bohemianism that speaks out through the players who visit the court, but whom Hamlet has met before, whose casuals contrast below with the one instance of nineteenth-century dress military uniform on the servant attending the court and welcoming in the players. T-shirts with emojis, coloured hair and liberties of individuated appearance all suggest cultural drift. Not least because the set contains mobile chests used by modern theatre companies, if not travelling medieval players (the ones below are labelled NTC and are clearly ordinary stock in the National Theatre Company). There is anachronistic sound machinery

Even in the retained Gravedigger scene, the Gravedigger (who is also a travelling player above and enacts the Ghost of Old Hamlet, with staring eyes in a British Imperial military costume) has a contemporary khaki cap and T-shirt, that matches the ‘modern’ but eclectic travelling gear of Hamlet on his return to England and here pointing to the skeletal mouth where once hung the lips of Yorick the court jester, which he has often kissed as a child.

Formal wear Is reserved for court activity against which small relaxations, like an untied bow tie indicate variation from formality and allow the egress of personal passion. This formal wear includes court fencing , an activity (probably French in origin) that indicates the playful court.

This gives power to the final confrontation between Hamlet and Laertes, in which so much relates to assumptions made about following unspoken protocols, like the bating of swords. Claudius invokes that fencing skill asa French import,the effect on Danish men in trying to ape that nation’s refinements and how easy it is to vary the protocol to ends the opposite of sociable. (Iv, vii 149

We’ll put on those shall praise your excellence

And set a double varnish on the fame

The Frenchman gave you; bring you, in fine, together

And wager on your heads. He, being remiss,

Most generous, and free from all contriving,

Will not peruse the foils, so that with ease,

Or with a little shuffling, you may choose

A sword unbated, and in a pass of practice

Requite him for your father.

Act IV, Scene vii, 149ff.

A difficult issue to work out for me though is why I find the family of Polonius so difficult to rationalise in terms of this production. Often played as slapstick (even the courtier’s death), interactions with Polonius by Hamlet are styled in a way I can’t read. The family group of Laertes, Polonius and Ophelia are often characterised by pastel shades and even white but this has no clear function. In a way I prefer Spall’s slightly evil Polonius in Ahmed’s Hamlet. That is because Polonius’ death is such an anomaly to the play though vital to its development. sometimes, despite its many beauties, I wonder if Hamlet is Shakespeare’s most messy and incoherent play, though I would lose nothing from it, because it all feels to matter.

The issue this production centres on is alienation effect, using the benefits of the Lyttleton’s traditional proscenium it mimics it with a proscenium within a proscenium, curtain space within a curtain space, and a Hamlet dressed in his most incoherent garb: ruff, t-shirt with cocktail suit on top.

The speech educating the actors stuck with me here more than usual. It gave me a reflective pause, when Hamlet says

Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced

it to you, trippingly on the tongue; but if you mouth

it, as many of our players do, I had as lief the

town-crier spoke my lines. Nor do not saw the air

too much with your hand, thus, but use all gently;

for in the very torrent, tempest, and, as I may say,

whirlwind of your passion, you must acquire and

beget a temperance that may give it smoothness.

Act III, Scene ii, 1ff.

That is because the direction of the acting in this production often emphasis over-interpretive gestures that felt over-done, in an acting style not of our post Stanislavskian age, but quite arcane (especially in Polonius’ family). There is a formality that isn’t quite that of the gestures of the town-crier but veering that way, and certainly not ‘gently’. For me this was yet another alienation effect: a reminder that what we are watching is a ‘performance’, even though for us as contemporaries all character is performance not reality – for reality is merely a performance to which you are accustomed. And the whole issue for Hamlet is ‘how to act’ if acting can be described as a falsification. That I don’t know how to act (in either sense) is for Hamlet an admission that being is no simple issue -but then so is ‘not’ being:

Now I am alone.

O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!

Is it not monstrous that this player here,

But in a fiction, in a dream of passion,

Could force his soul so to his own conceit

That from her working all his visage wanned,

Tears in his eyes, distraction in his aspect,

A broken voice, and his whole function suiting

With forms to his conceit—and all for nothing!

For Hecuba!

What’s Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba,

That he should weep for her? What would he do

Had he the motive and the cue for passion

That I have? He would drown the stage with tears

And cleave the general ear with horrid speech,

Make mad the guilty and appall the free,

Confound the ignorant and amaze indeed

The very faculties of eyes and ears. Yet I,

A dull and muddy-mettled rascal, peak

Like John-a-dreams, unpregnant of my cause,

And can say nothing—no, not for a king

Upon whose property and most dear life

A damned defeat was made. Am I a coward?

Act II, Scene ii, 575ff.

But the one thing Hamlet can and will not do in the text considered in full is act for the good of others, though Riz Ahmed makes him go some way towards that position. That’s the end of my open-ended thoughts on my week of Hamlets. If you want to shoot someone after all, you have to begin with a real gun and know whom you are firing it at.

Bye for now

Love Steven xxxxxxxx