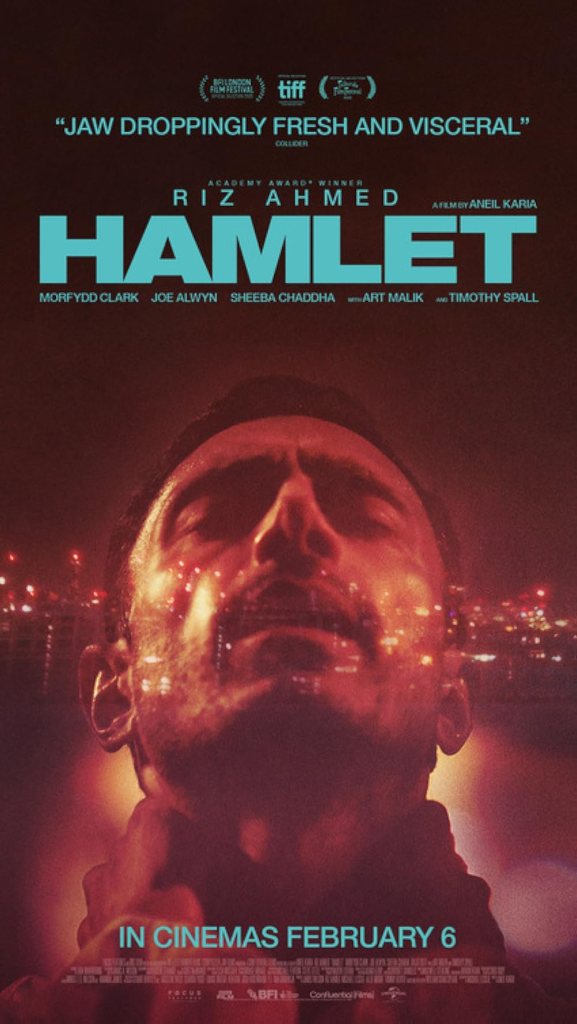

A week of Hamlets: [1] To start, there is a tendency to see Shakespeare’s character Hamlet as a part nightmare dream version of one’s autobiography. Riz Ahmed has won the prize for the finest version of such projects.

For a long time, literary critics have insisted that to see elements of the biographical in the charismatic figures that are the leading energy of dramatic plays, especially, those by Shakespeare is a’big mistake’. Many, however, have al;so felt that an exception might be made with the character of Prince Hamlet in the eponymous play. Here, for instance, is a stern critic, Barbara Hardy, from 1958, excusing Coleridge for a thoughtless identification with the dark prince.

However, later artists invented their own Hamlets to express the tedium of despair that was quite clearly not only biographical but autobiographical, as with Tennyson in inventing the speaker in Maud. And so on to dramatic and film directorial artists. We now have Riz Ahmed, surely offering us a Hamlet in himself and in his insistence, brilliantly beautifully done, to make the entire play a biography of a despairer, an autobiography of his youthful identification with the character. I suppose the point is that we oft give our own autobiography a make-over in the form of a heroic type with whom we identify, even if ‘only a smak’ in Coleridge’s case.

Cited in Katie Spencer’s piece on Sky News, Ahmed says of his Hamlet:

“Hamlet is feeling the way a lot of us are, you know, he’s feeling the world’s an unfair place,” he tells Sky News. “He’s powerless about it. He’s being gaslit about it. He’s complicit in it… and a lot of people feel that way.”

But perhaps they especially feel at the time they are studying Hamlet for the first time, as an aspiring actor.

Ahmed says he became “obsessed” with the story as a teenager.

“I had an amazing English teacher who gave me the play to look at because he saw that I was feeling out of place.” [1]

Feeling ‘out of place, is, in effect ,feeling that one is not up to the challenges the present time, and circumstances of place are setting one. It is a common feeling in adolescence, if not universal, such that there seems a kind of generality in Hamlet saying at the end of Act 1 Scene V:

The time is out of joint. O cursèd spite

That ever I was born to set it right!

It’s a generalised feeling and it in part restates what Nietschze called ‘the Wisdom of Silenus’:

But in Hamlet’s case it expresses something more than a generalised desire not to have been born but a desire not to be born in the social status I was born in which the duty to ‘set the time and place’ in which I was born ‘right’: such hopes and expectations do princes inherit at their birth. In Ahmed’s case, it appears that a generalised sense of being ‘out of place’ and unable to fit in the role allotted to one, as one sees it, led him to think of what role in life might most duplicate a sense of responsibility that it would be best to escape in modernity – in the world, that is, of late capitalism.

However, in such a world are we mainly deterred from wishing to fit in either because we see this world as ‘sordid’ or because we feel inadequate for fulfilling its roles to our own standard – by turning a ‘sordid’ world into something more beautiful perhaps. For most people at teenage and early youth, at least in my day, there was a bit of both of these feelings, which are in a sense contradictory, involved. And so it might have been, and perhaps still be, for Ahmed, of whom Spencer says:

In the past, the actor has admitted being an “obsessive perfectionist” when it comes to the projects he works on. When asked if becoming a dad might have seen a shift in Ahmed’s focus and made him a little less intense to work with, the pair crack up laughing. [1]

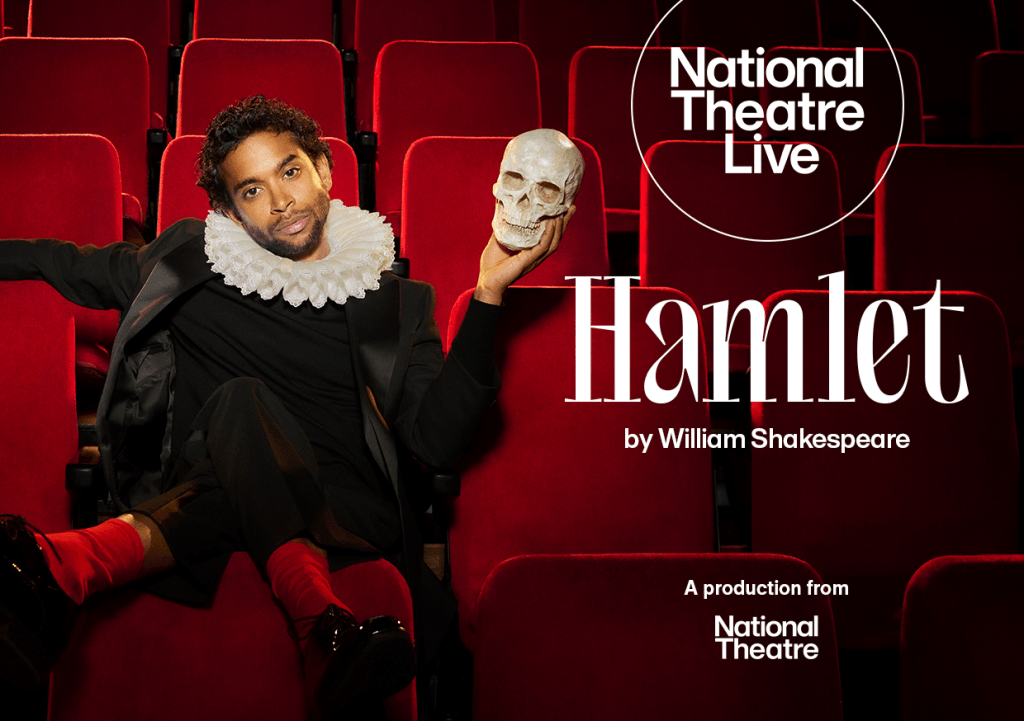

Image: Ahmed says he was ‘obsessed’ with Hamlet when he was a boy. Pic Reuters (source: Spencer op.cit)

It seems the laughter from both Ahmed, and his director, Aneil Karia, resulted from the fact that, seeing that Hamlet might be a play about fatherhood, fatherhood is merely one of the social roles we oft reject or wish ourself out of or are tortured by visions of how to be the perfect father. But late capitalism is certainly a burden that scores itself through Hamlet’s soul, as the rows of lights of a London landscape over, through and behind the Hamlet persona suggest in the poster – here again:

For me watching the film, for the first time, exposed me to the jars one might expect when so much of the play is known and sings its rhythmic verse in my head. This production is according to Elizabeth Schafer, a Professor of Drama and Theatre at Royal Holloway College, University of London: ‘a radical adaptation that mostly uses Shakespeare’s words but relocates to contemporary, uber-wealthy south-Asian London’. She calls the script by screen writer Michael Lesslie a ‘collage’ [2] Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian is perhaps more specific in saying how you create a ‘collage’ of a Shakespeare play:

Screenwriter Michael Lesslie and director Aneil Karia have devised a stark and severe new interpretation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet; there are transpositions and cuts, some light modernisations, and the text is stripped down a good deal. [3]

But it is the ‘transpositions’ that get me most, as the role of Laertes is expanded to include reception of speeches delivered by Hamlet to Horatio, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The latter pair are cut from the play as is the sojourn abroad mid-play, or the fact that a speech is delivered to Ophelia (not Horatio (in Act 1, Scene v,, c. 186) directly – face to face in her flat – that Hamlet will be play-acting madness (an antic disposition’) after this point. This all makes her fearful response to Hamlet’s later anarchic sexual and identity disorders harder to interpret. But maybe those transpositions are easy to take once you know the play is set in London, Elsinore is, in Shafer’s words, ‘ the ruthless family business of developers and builders’.

But they are not only ruthless internally to their own family members – enforcing marriage contracts to protect the firm of ‘Elsinore’ (including Gertrude’s (Sheeba Chadha) re-marriage to her brother-in-law, Claudius (Art Malik), but also a projected financially sound union within his own culture, cutting off his childhood ‘understanding’ with Ophelia and ensuring the loyalty and secrecy of family members – but also in its land and property deals.

We soon learn that the London setting of the events, when not in the rich mansion of the family, is on the half-built, half-demolished land won by subterfuge and illegal deals and involving its depopulation of its once settled, and migrant, populations. When Hamlet sees the Ghost of his Father, the ghost leads him alone to the top of a half-built ugly building that is clearly Elsinore-properties owned. Again as Schafer says, showing how characters and their interactions and inter-relationships are bound together:

Ophelia, like Hamlet, is disgusted by corporate corruption although, as the daughter of Claudius’s chief adviser, Polonious (Timothy Spall), she benefits from Elsinore’s rapacious deals. But as Laertes tells the pair, she is no bride for the future head of Elsinore. An arranged marriage within his culture and one that is advantageous for Elsinore is assumed to be in store for Hamlet. Overwhelmed by the nightclub music, dance and drugs, Hamlet flees out into the night and a decaying London, with skyscrapers on the horizon and walls graffitied with anti-Elsinore slogans. [2]

Polonius tries hard to match the rather silly diplomatic foolishness of the original Polonius, but is played (brilliantly by Spall) as a man worthy of his rather visceral death – however much an accident.The graffitoed walls are the work of Fortinbras, revealed to us by a newspaper headline caught by the camera to be an organisation, under a captain given the same name, of the dispossessed of Elsinore property grabs, liquidations and over-profitable rebuilding in the interests of the few.

Hamlet’s misogyny, deeply rooted in the original play, is perhaps a hint more playful in Ahmed’s playful drag-in-bejeweled-saris and the pain of Ophelia (Morfydd Clark) is nuanced oft with laughter, that doesn’t only disguise some of the pain, though we know Ophelia finds cruelty in more than Hamlet. Her pain at her father’s death by Hamlet’s hand is done so brilliantly there is no need for the stereotyped(by sixteenth-century standards) ‘mad scene’. Hence I disagree with Peter Bradshaw that we miss this scene, as with comic Gravediggers scene and ‘alas, poor Yorick …’. Clark is worthy in the role.

This is a play in which masculinity is confronted as a thing performed in intersection with class and other kinds of formal status, as in the still below. But what marks out this still is the audience-eye-catching gaze of Hamlet from within his rank: beneath that of Art Malik’s Claudius but above Joe Alwyn’s embodiment of Laertes. Hamlet seems to want an audience to ally with him, assert that his discomfort in space and time is understandable – hence his attraction asa young man with whom other young men will wish to identify.

But surveillance, even ours, also traps this Hamlet, where even wealth, status and cultural wealth speaks of isolation.

But the most violent thing in the play is not even the gut-turning murder of Polonius but the transformation of the scene usually called the ‘play-with-a -play, ‘The Murder of Gonzago’. It is played in this film as a traditional Indian dance, described well by Schafer:

The brilliant choreography (by classical Kathak dancer Akram Khan) reads, within the logic of this film’s narrative, as a direct threat of violence towards Claudius. The dancers’ fists create a funnel for poisoned wine to be tipped into the dancer Gonzago’s ear while Hamlet, apparently deranged by grief, watches eagerly.

Violence is a demon-god in Ahmed’s Hamlet, and the use of Indian dance is true to the fearsome stories it tells from the pantheon of Hindu Gods and heroes of religious narratives – hands soaked in symbolic blood, making a group seem the embodiment of a singular supernatural demon that makes us watch suffering in ways that makes us partake of it and its violence. Of course the scene-stealer is the performance of the ‘To Be Or Not To Be’ soliloquy by Hamlet in a speeding car, in the wrong lane with increasingly fearful, vehicles coming at him by his own volition, with his hands off the wheel. But it is one of many that make male isolation feel a terrible thing – bound up with alienation too from role and even the pleasures associated with youth, with scenes of abandoned pleasure often back-dropping moments of haunted ennui, driven by a search for meaning that has no blueprint for the meaning it seeks. Isn’t this how we imagine our own autobiographies?

Bye for now. We see the screened National Theatre Hamlet on Thursday night. See you again, I hope.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

_________________________________________________

[1] Ahmed cited: Katie Spencer (2026) ‘Riz Ahmed hopes his modern-day ‘visceral’ Hamlet will be shown in schools’ in Sky News (online) (Sunday 1 February 2026 01:50, UK) available at: https://news.sky.com/story/riz-ahmed-hopes-his-modern-day-visceral-hamlet-will-be-shown-in-schools-13500995

[2] Elizabeth Schafer (2026) ‘Riz Ahmed’s British south-Asian Hamlet is a moody tale of grief and shady family business’ in The Conversation (online) [Published: February 5, 2026 6.12pm GMT} available at: https://theconversation.com/riz-ahmeds-british-south-asian-hamlet-is-a-moody-tale-of-grief-and-shady-family-business-275056

[3] Peter Bradshaw (2026) ‘Hamlet review – Riz Ahmed’s tortured prince drives chilling modern take through London’s streets’ in The Guardian (online) [Thu 5 Feb 2026 07.00 GMT] available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2026/feb/05/hamlet-review-riz-ahmed-timothy-spall-art-malik-aneil-karia

One thought on “A week of Hamlets: [1] To start, there is a tendency to see Shakespeare’s character Hamlet as a part nightmare dream version of one’s autobiography. Riz Ahmed has won the prize for the finest version of such projects.”