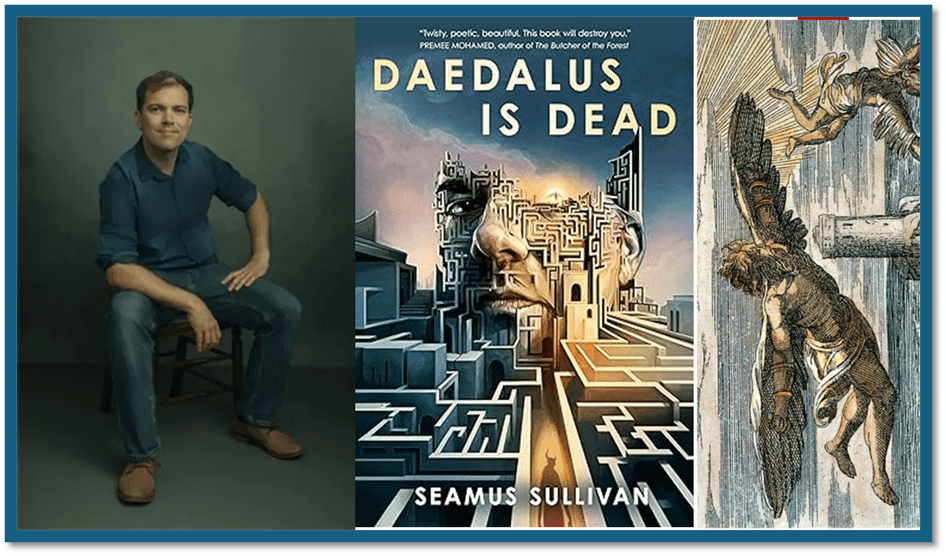

Ask that question to Daedalus? Would he uninvent the Labyrinth? In Seamus Sullivan’s bold debut novel his character, Persephone, the (part-time) Greek Goddess of the Underworld, informs her prominent subject, the dead Daedalus, that, ‘Heroism isn’t strength or bravery,…. It’s the conviction in your innermost heart that the entire story is about you’. This blog discusses a superlative addition to much of the chatty mess that is the novel focused on sex/gender based on Greek mythological heroes: Seamus Sullivan (2025) Daedalus Is Dead London, Tor, Pan Macmillan.

Daedalus has long been used as the mythical archetype of the artist-technician (the distance between the two is short in Greek, even a playwright like Aeschylus glories in his skill in techne). James Joyce combined the two in A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man by naming his young avatar Daedalus or Dedalos, the ‘name of the fabulous artificer’. He is the man who invented or mentally conceived and constructed purposive structures and tools responding to the needs of the moment yet with acuity and genius. We don’t think of such men, how fabulous their overreach of necessity as heroes necessarily. Sullivan’s Daedalus denies he is a hero. He thinks this fact ought to make him immune to the lust for the blood of heroes of the Minotaur. He and Ariadne had decided, he, now dead, tells Persephone, the (part-time) Greek Goddess of the Underworld that the Minotaur (The Bull of Minos but once the son of Minos named Asteirion) had developed an appetite for ichor which runs like molten gold in heroes’ blood, as with Gods.[1]

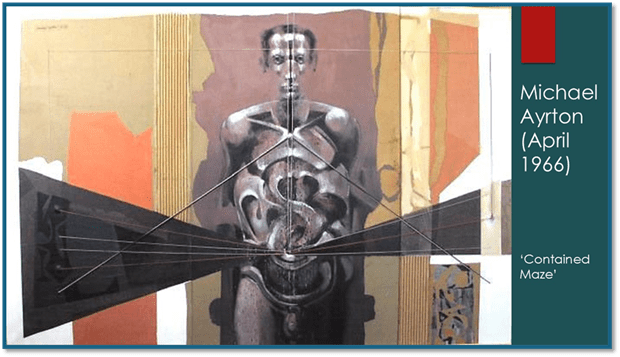

Bur artists or artificers (artists of the technical) may also be heroes, this novel suggests, for heroism is less a thing of glorious deeds but of the placement of self in narratives that tell of those deeds, or, as Persephone puts it: ‘‘Heroism isn’t strength or bravery,…. It’s the conviction in your innermost heart that the entire story is about you’.[2] I think Persephone gives this definition in order to redefine heroism in a way in which it fits Daedalus entirely, as a narrator whose stories in plot, ‘built’ or natural setting and character, are just another type of his cunning inventions and constructions, and are all speaking of him. The idea is not new, of course. The artist most obsessed by Daedalus as a figure of the artistic self mediating between interiors and exteriors as novelist and sculptor is Michael Ayrton.

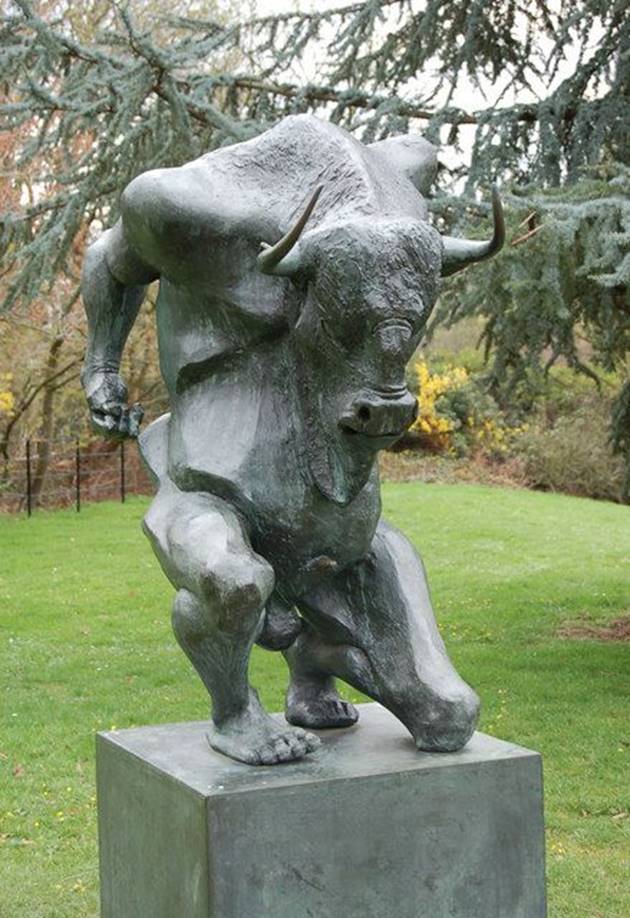

For Ayrton (and, Ayrton would argue, for Picasso too) the maze and the bull of Minos exist inside the visceral-psychological workings of the artist and is pulled forth to external vision only to endager anyone outside that interior, even the artist himself, if the maze within loses its continment within its gracious bodily walls.

In Ayrton, Daedalus the artist even could explain other classical mythic tropes such as that of the Laocoön . These figures of conf contained or released (and dangerous maze-type structures are capable of manifesting the unexpressed, and sometimes inexpressible and repressed (in the terms of this Lethe centred novel novel, forgotten), characteristics of inner rage, lust for power and sexul capture, and, defensive structures that pass for an appearance of grandeur.[3]

Prometheus in Sullivan’s novel says to Daedalus that the later artist was influenced by he architecture of interiors and exteriors that allowed the Titan God to invent humankind, as a complex of inner passages and bold and beautiful defencsive walls. When the Titan awakes, Daedalus records how he:

… talks cheerfully of how his designs must have influenced mine, for what is the human body, with its branching veins and winding bowels and many-chambered heart, if not a Labyrinth?[4]

Sullivan wants his Daedalus not only to be the controlling magus, although the control like the lust is not all conscious to him, or at least made available to his auditors. More than twice, but twice to each of the women in his life, interlocutors catch Daedalus out in recounting ‘false memories’ which minimise the scale of his sexual and power-seeking perfidy against that very interlocutor in the past: once to his estranged wife, Naucrate, and once to the young and virginal Ariadne, whose approach to her in bed is a near rape.[5] Perhaps the scale of his perfidy is greatest in his stories to Icarus, even that of his fantasy of a long stay, in which he semses that he is followed or hunted (there is a strange relation between these concepts) by the Minotaur, in the Labyrinth but in fact stayed only half-an-hour: these memories are near-psychotic.[6]

There is a close connection between the erected monuments of Daedalus’s art and the potency of a certain construction of masculinity that the novel illustrates, although always as if that construct were external to Daedalus himself, who sees himself as a mere servant of great men, keen to use him to build symbols of their poer, authority and charismatic allure as many men in his imagination and again in reality – notably of course King Minos of Crete, for even in Tartarus, where other giants are tortured for their male pride – the Titan Gods, ‘Minos towers over me’. Phallic towers is what Minos’s statue in Hell represents to Daedalus – a structure he is attempting to dismantle that continually re-erects itself. Fragments of Minos’ statues musculature that have masculinity burnished into thir very names, Daedalus uses as a staircase to ascent to the heights of those ‘hero’s’ hubris: ‘Shattered pectorals’ fragments of regal forehead. …, calves and biceps and buttocks and shoulders, stacking and cementing the pieces to make a gruesome staircase’.[7]

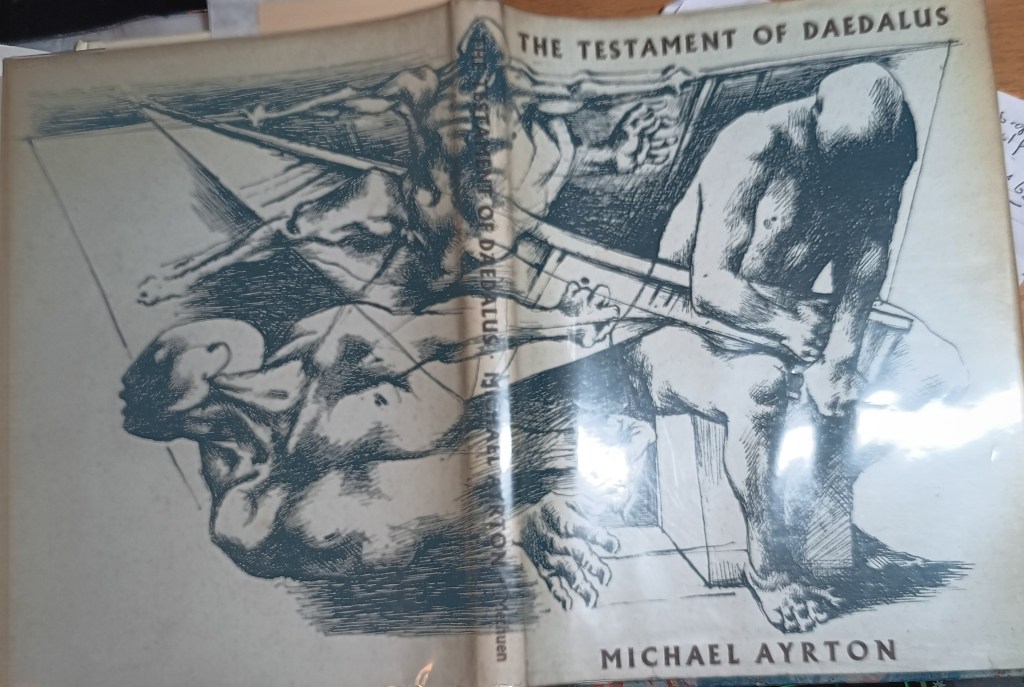

My copy of Ayrton’s (1962) The Testament of Daedalus

Even talking to his son, Icarus, Daedalus however seems to distance himself from Minos’ hubris though he serve it as a tool and with creative expression. Bulls are an ideal expression of a masculinity that rages but in a wonderfully funny exchange between Daedalus and Icarus as a playful infant, urging his Father to act as if Perseus and ‘slay; the sea monster he believes he is, Daedalus explains why he rejects a design for the external wals of the Labyrinth – a prison for a bull calf / boy hybris, Asterion – painted by himself with a ‘prison ship shaped like a winged heifer’.

“Minos was cuckolded by a bull. The child has unmanned him. He’ll never admit to this. He wants both a prison that hides his shame and a monument that shows off how manly he is.”

Icarus, of course is too young to understand this and says,”What’s unmanned?”, to which daedalus says: “An architectural term. We’ll cover it later.”[8] But to call unmanned an architectural term is more than a deceptive ploy used to an innocent child, it is an admission that architectural art and sexual and maculinist monumentality to powerful men are the stuff of Daedalus’s work. Just as Minos adopts Asteirion, the son of a bull, he also appropriates ownership of his maculine nature: the term Minotaur meaning the ‘bull of Minos’, glorying in its growth to huge size and consummate and specialised appetite for male flesh.[9]

Yet Daedalus himself, his own life isearly in the book, as he as an old man reflects back on his life, sees himself metaphorically as if he had always, even when holding his child Icarus in his arms, been housed in the Labyrinth, as if he were the Minotaur nd Icarus, the young Asteirion: ‘those places too were part of the labyrinth, and always have been’.[10] In some sense the ‘Labyrinth enfolded’ him at all times, whilst in Crete, or ashe flees it or once dead,[11] making him a poor father, husband and friend to Ariadne (who though him a safe space but found him sexually predatory). Icarus identifies with the young Asteirion and fears his loneliness, comparing it that caused by his father’s neglect when building his artwork-prison, wonders if his father is kind to Asteirion as he wonders if his father is ‘angry with’ him.[12] Daedalus’ vision of being trapped in with the Minotaur is his vision of being able to project the Minotaur’s followin ‘cip-clop’.[13] There is a clear indication that the construction of the Labyrinth becomes a means of constructing, out of Asteirion, the monster that is the Minotaur: ‘there he was, seeming to spring from the rock itself. An ageless fiend, hewn from the earth with the rest of the place’.[14]

As Minos turns against him, he imagines himself and icarus trapped together but apart – unable to see each other – but essential a prisoner of Minos lie the Minotaur is, and Asteirion was, unless he takes his place by taking Ariadne, his daughter. The last idea is only suggested in a vision of freedom strangely indicative of building a palace for himself and her but stinking of ‘sweat and dirt’.[15] It is he, who magnifies the threat of the Labyrinth beyond Cretans to the entire Greek world.[16]

None of this would be possible were it not that the social function of the masculine, and the power to enact that function, were not themselves created ambivalently. Men offer their families security as Kings and heroes supposedly offer the same to nations. Daedalus, from the beginning of the novel, insists to the absent Icarus he addresses that Icarus ‘could not know the lenghs I wnt to, to keep you safe’.[17] Yet in Hell, his dead wife Naucrate seems to insist that only she can ‘kee’ Icarus ‘safe’. We may, even then begin to wonde, if that means, keeping Daedalus away from him.[18] For there is something wrong with the way sometimes fathers, use their masculine role, to ensure the safety of others; women, girls and boy sons. Men secure the wherewithal of ‘homes’ to shelter families, but a the many-chambered heart of the novel is the Labyrinth, a home hat is also a prison, built at the command of a father for his step-son, a place with ‘Walls but no rooftops. Doorways but no dours’ – apparently open but nevertheless the more confining. For King Minos it is a ‘public safety measure’ this home for his son who will grow with his home into a monstrous being in a structure, ‘open but impenetrable’.[19] Minos instructs Daedalus thus:

You are to build his home …. It is to be impregnable, inescapable, And grand … He is not to be chained or confined.[20]

Buildng homes is building prisons however for more than Asteirion, and without. Even in Hell, whilst he chases each hint that he could follow to Icarus’ wherabouts it is you build him a home of his own design, a way ‘to hold you in my memory, to keep you in a place where the mist can’t scour you away’.[21] The mist is that of a waterfall in Lethe causing forgetfulness, but wheras dreams of building a home ‘hold’ and ‘keep’ the memory of his son, do they also trap and contain him from flight – the same flight that lead to the only way Icarus could escape the pursuit of his father, by flying up to his inevitable death. For other people, Daedalus provided the idea of a permanent homes that became a trap, from which only flight could guarantee escape. Thus for Naucrate, thus for Ariadne, trapped on a bed with Daedalus using his reputation for being ‘safe’ in her eyes to demand a sexual favour, Believing that he once Ariadne to flee with him and Icarus from her monstrous father, she says to him when they meet on Olympus:

“You asked for more than that. I said no in every way a person can say no.”

…

“You climbed onto my bed that morning, … You grabbed my hand. You said, ‘We’ve waited and waited. What sense is there in waiting any longer’.[22]

Daedalus loves innocence, but, as with Asteirion, there is no guarantee he wants innocence to say as such. On Olympus he notices young, apparently heroic, male flesh as much as he believes the mature Minotaur delights in, if with a rather more tearing appetite, noticing ‘preternaturally beautiful young men waiting beneath one of the archways leading out’. They could be: ‘Minor gods, or mortal princes kidnapped for their good looks’. Immediately after he notices a ‘beautiful boy carrying a tray of empty goblets and dishes almost runs into me. I dodge, then retrace his steps, passing more servers’.[23] In a novel where people follow other people or alternatively make themselves unfollowable by escaping alone and in secret conditions, this act of following seems to matter. Following another, or being followed can also be a chase, even a ‘hunt’, in which the clip-clop of hooves can be heard, whether the Minotaur is real or a projected Fantasy of a desire that may be Daedalus’ own. Trying to find his son behind the waterfall and its circumnambient mist that was once the River Lethe, the river of forgetfulness, Naucrate – who fled Minos, Crete and Daedalus (leaving her son behind) has to tell Daedalus that Icarus that she believes Icarus “didn’t want us to follow”.[24]

Icarus thought his father a hero. In an important game he asks his father to enact Perseus and kill him with a spear, because he is a ‘sea monster’. What are we to make of this. Heroes matter to the boy thereafter, as they aslo do to his contemporary Asteirion, another lonely boy abandoned by his father, for a different reason. Daedalus buys him an ancient scroll of the heroic adventures of the hero king of Uruk, that is The Epic of Gllgamesh (not mentioned in the text so directly) telling of the love of the hero king for Enkidu. They make ‘little sense’ to Daedalus these sories.[25] And heroes are not for him to understand, as he misunderstands Theseus who lets Ariadne go becausethat is what she wants, having fled withhim to escape Daedalus.[26] And Daedalus worries that Icarus wanted to be a hero and talks heroes down to his son.[27] But I entitle this blog after Persephone’s definition of heroes, one much morefitting to Daedalus than Theseus – someone who ensures he narrates his story to make himself its centre – however dispersed its centre seems (the very definition of a Labyrinth). Daedalus is the hero by virtue of being his own narrator, figting against Lethe and the ‘forgetfulness’ of others.[28]

Daedalus is an ambivalent man, apparently gentle and loving but attracted to power and control strategies. However this also applies to him as an artist. Drawn to the most power ful patrons, like Minos and Persephone, he constantly seems to court imprisonment by hem, even if informal (based on n agreement never to quit or flee). Escape as an artist into one’s own autonomy seems impossible to him – hence the need of others dependent on him to escape him in ways that make them unfollowable virtually. Even in Sicily where he says: ‘I’m free to come and go’, he dds ‘although I don’t’.[29] When Icarus wqrites a rebellious youthful poem against Minos, Daedalus burns the tablents on which it is scribed. He does not challenge power, ever – for anyone. That his atory is about art seeking free creative expression is only possible to understand, if we see the reason why Icarus is an artist too. Constantly querying why Icarus left him and aspired to the sun, to Apollo perhaps, he imagines late in the nove, Icarus living a free (almost Bohemian – if that weren’t an anachronism for a Greek) life, he sees in Icarus a model of art that refuses to be servile, or even accommodate the powers-that-be in the status-quo.

A life spent avoiding kings and warriors and too much time indoors. Refusing to be hemmed in by walls. Trapping Minos, and the Minotaur, and your father in rhyme and meter where they couldn’t hurt anyone.[30]

Notice that Icarus alive has no option but to imprison those who do harm – as Minos / Daedalus do the Minotaur in the labyrinth, but the trap is the web of a verse narrative only, not a thing of solid technically perfect and decorated walls, such as Daedalus creted, togeher with palaces and statues that flattered power. We can only hope, wherever Icarus is, in this novel, he is free of Daedalus as a father and artist, whose role contributes to the harm in the world rather than alleviating it.

That’s all for now. There is no dount that Daedalus ought to univent the art of labyrinths that hide things and glory in spilled blood and ichor, even eat off it, but I doubt he ever will. As Daedalus ends the novel, he is still following Icarus, but is doing so to learn from his son or to chase or hunt him. Isn’t that why he hears the ‘gleeful snort’ behind him, ‘his clip clop clip clop gathering speed’, for daedalus is one with Minos, his patron and the Minotaur, brandishing phallic equipment as in Ayrton sculpture belowhis co-creation with the Labyrinth out of a victimised boy.[31]

People don’t uninvent evil. They have to have their power wrested from them, or if not – mitigated!

With love

Steven.

[1] That mortal heroes had ichor in their blood is not an attested belief entirely, certainly not in Wikipedia which claims that contact with flowing ichor was fatal to mortals. Of course heroism sometimes associated with a status change from mortal to divine, but Sullivan uses it too show, it seems by inference from the story told, that the degree of ichor was analogous to the degree of heroism and hence component of immortal in mortal flesh.

[2] Seamus Sullivan (2025: 146f.) Daedalus Is Dead London, Tor, Pan Macmillan

[3] See Jacob E. Nyenhuis (2003) Myth and the Creative Process: Michael Aryrton and the Myth of Daedalus, the Maze Maker Wayne State university Press, Detroit, USA

[4] Seamus Sullivan, op. cit: 75

[5] Ibid: 83f. & 147 respectively.

[6] Ibid: 72f.

[7] Ibid 48 – 51.

[8] Ibid: 22

[9] Ibid: 38

[10] Ibid: 10f. (my bolding). But see the recurrent dream ibid: 26,

[11] Ibid: 115

[12] Ibid: 40

[13] Ibid: 63

[14] Ibid: 42

[15] Ibid: 91

[16] Ibid: 100

[17] Ibid: 10

[18] Ibid: 32

[19] Ibid: 33

[20] Ibid: 20f.

[21] Ibid: 47

[22] Ibid: 147f.

[23] Ibid: 141f.

[24] Ibid: 82 (read 81f.)

[25] Ibid: 62

[26] Ibid: 108

[27] Ibid: 113

[28] Ibid: 81

[29] Ibid 11.

[30] Ibid: 153

[31] Ibid: 161