‘Leisure’ is one of those few words that has not much change its range of meaning from its etymological origins – although the analogy with ‘pleasure’, and the adoption of a spelling change from that association is interesting.

leisure (n.)c. 1300, leisir, “free time, time at one’s disposal,” also (early 14c.) “opportunity to do something, chance, occasion, an opportune time,” also “lack of hurry,” from Old French leisir, variant of loisir “capacity, ability, freedom (to do something); permission; spare time; free will; idleness, inactivity,” noun use of infinitive leisir “be permitted,” from Latin licere “to be allowed” (see licence (n.)). / Especially “opportunity afforded by freedom from necessary occupations” (late 14c.). “In Fr. the word has undergone much the same development of sense as in Eng.” [OED]. The -u- appeared 16c., probably on analogy of pleasure (n.), etc. To do something at leisure “without haste, with deliberation” (late 14c.) preserves the older sense. To do something at (one’s) leisure “when one has time” is from mid-15c.

It is interesting because ‘leisure’ once, it appears, and certainly in Shakespeare, had little or no truck with pleasure and much more with power and status or resources (especially of time), for it is those latter two qualities that gave men (usually men) the opportunity to take their time over decision-making-making about the right action to take in any situation. Mark Anthony asks Cleopatra to take time at her ‘sovereign leisure’ to read of Fulvia’s death in Rome, the leisure befits the power and status of sovereignty (Anthony & Cleopatra Act 1, Scene III, 71). When Osric addresses Prince Hamlet he checks that he has time to read the news he brings to him:

Sweet lord, if your Lordship were at leisure, I

should impart a thing to you from his Majesty. (Hamlet Act 5 Sc.II, 102f.)

This too implies that Kings and Princes may have ‘time at their disposal (what leisure is) but that it may not be assumed to be available by an underling without the noble person’s expression statement of the case. When the Duke of Worcester addresses his nephew, Henry ‘Hotspur’ of Northumberland, he bows to the younger man’s status as a warrior, not of rank, but also keeps checking that such a hasty man has the time to spare, even double-checking that when he says he has finished his speech, he really has done :

HOTSPUR: ....

Good uncle, tell your tale. I have done.

WORCESTER: Nay, if you have not, to it again.

We will stay your leisure.

HOTSPUR: I have done, i’ faith. (1 Henry IV Act 1 Sc.III, 265ff.)

Hotspur himself (his very name a sign of a hasty aristocratic cavalier) can even invert the normative power relations between father and son, when his father fails to attend the battle in which Hotspur leads the charge against Henry IV (Hotspur is a rebel and hence used to inverting normative power relation). Her comes the Messenger to tell him his father’s situation:

MESSENGER: He cannot come, my lord. He is grievous sick.

HOTSPUR: Zounds, how has he the leisure to be sick

In such a justling time? (1 Henry IV Act 4 Sc.I, 18ff.)

He merely means that in civil war, time is at a premium and you have to make time, even if you are my senior, but there is a hint of the modern meaning too – since Hotspur must suspect the truth: that his father is not ill at all but merely afraid of the result of the oncoming battle and his fate under the King should he join in. The sarcastic use of the word is bettered though by King Lear, when he finds his daughter Goneril unwilling to allow him to stay with her with his retinue of a hundred knights. He thinks he still has power over her, as a father and former King, and can allow her to take time to reflect, for, after all, he says, I have other options; I can stay with your sister:

Mend when thou canst. Be better at thy leisure.

I can be patient. I can stay with Regan,

I and my hundred knights. (King Lear Act 2 Sc.IV, 251ff.)

The irony of his assumption is that both his daughters now have more power than he and will use their time to act at their own pace as sovereigns decide, not abdicated Kings command, without the de facto power to do so. When he says to Goneril take as much time as you like, he barely recognises that he will have a lot more to be ‘patient’ about than he thinks when Regan rejects him and he is thrown out onto the heath. In this case as others though, in effect ‘leisure’ is the opposite of ‘haste’ in action, a point underlined in the most famous line of Measure for Measure.

Haste still pays haste, and leisure answers leisure;

Like doth quit like, and measure still for measure.—(Measure for Measure Act 5 Sc.I, 466f.)

The effect of the Duke’s first line is that if you act hastily you get hasy action back, and that it pays you take your time in your decisions and actions if you want the same in return – the line is entirely is entirely about attitudes to time and the use of your powers in it.

Shakespeare being Shakespeare, of course, some uses are more subtle, as in the sestet of Sonnet 30 below:

O absence, what a torment wouldst thou prove

Were it not thy sour leisure gave sweet leave

To entertain the time with thoughts of love,

Which time and thoughts so sweetly doth deceive,

And that thou teachest how to make one twain

By praising him here who doth hence remain.

Note that choosing to be absent from Shakespeare, his lover exerts his power over the besotted Shakespeare to use his time as he will – hence it is ‘sour leisure’, since it has a sour effect on Shakespeare, even if it forces him to accept he has time on his hands too now, without his lover. But that leisure is also ‘sweet leave’ (meaning both a given permission and a spell of time) which can be filled with his current pleasure (or entertainment), thinking about his lover if he cannot be with him. What is clear is that ‘leisure’ here is not in itself ‘pleasure’ for pleasurable indulgence is not the only or main way of filling spare time.

How different now, where leisure-time is usually the binary opposite of work time or time in which we have to ‘care’ about what we do. That is most telling in W,H. Davies well-known poem better known than its title, Leisure:

WHAT is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare?—

No time to stand beneath the boughs,

And stare as long as sheep and cows:

No time to see, when woods we pass,

Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass:

No time to see, in broad daylight,

Streams full of stars, like skies at night:

No time to turn at Beauty's glance,

And watch her feet, how they can dance:

No time to wait till her mouth can

Enrich that smile her eyes began?

A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

Life needs the balance of time to be busy and time to do nothing at all but enjoy those moments when we ‘stand and stare’. Written in 1911 by Davies however, the poem comes from a poet whose response to the world of care and responsibility was to retreat from it. The only riches in life (‘poor’ without it) is taking as much time watching others ‘hide their nuts in grass’ not doing it yourself. Davies stance was thought of as ‘bohemian’, and even defining that term together with his predecessor, the fictional The Scholar Gypsy of Matthew Arnold, to whom Arnold declaims:

—No, no, thou hast not felt the lapse of hours!

For what wears out the life of mortal men?

'Tis that from change to change their being rolls;

'Tis that repeated shocks, again, again,

Exhaust the energy of strongest souls

And numb the elastic powers.

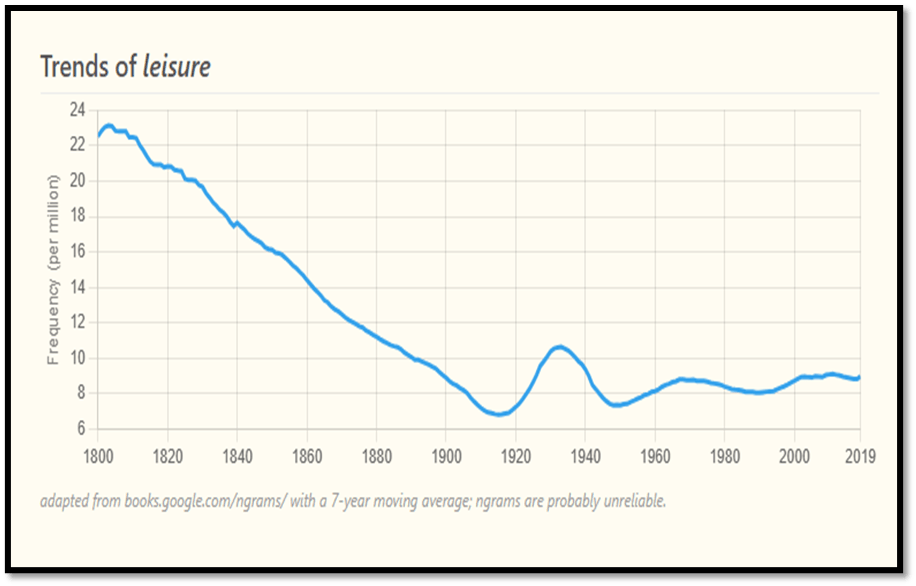

But where in this world can we find this leisure to escape all time, all change and ‘wear’, where even ‘leisure’ is an industry – in my view for its consumers too working hard at eking out pleasure from that leisure, rather than just escaping time by its imagined or real evasion. And id we go back to etymology.com on leisure, look at the chart of its changing frequencies over time in written text (remembering that n-grams are not considered statistically valid or reliable).

The sharp decline in frequency of use from 1800 to 1900 more or less covers the white heat of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of alienated labour practices in capitalism, not even rising to half the frequency of the word in 1800 even in twentieth-century peaks 1920-30 and even in 2019 not apparently rising dramatically. So when I ask myself how I use my leisure time, I wonder first of all if I really have any such time, distinct from ‘the change to change’ through which my ‘being rolls’. And I keep on remembering though ‘sheep and cows’ just ‘stand and stare’ for a log time, it is just a fraction of time until they are called to be somebody’s meal.

All the best

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx