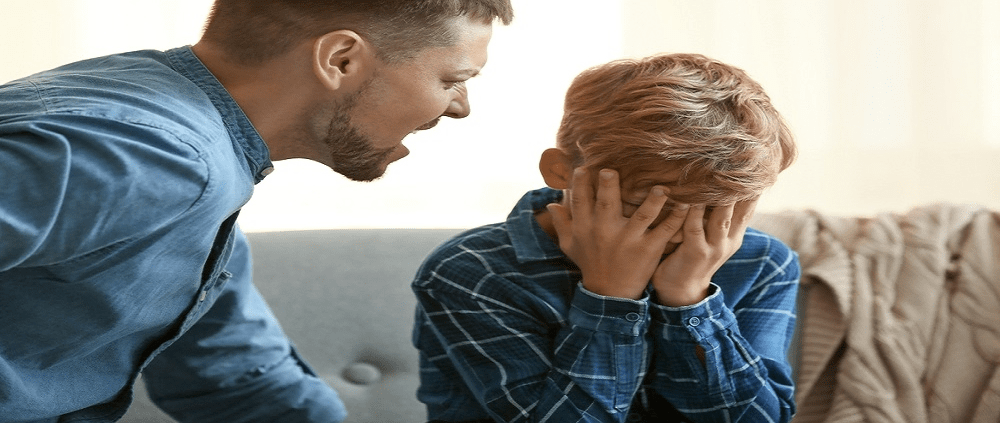

‘He’d now the power he ever loved to show, / A feeling being subject to his blow.’ In 1810, a long time ago, a rhyming vicar, could trace the origins of domestic abuse to the leeway given to men to ‘assert the man’ by the exercise of power and control. Why is it possible to see no end of this leeway in the future?

Detail from Theatre Royal Newcastle page: https://www.theatreroyal.co.uk/whats-on/peter-grimes/

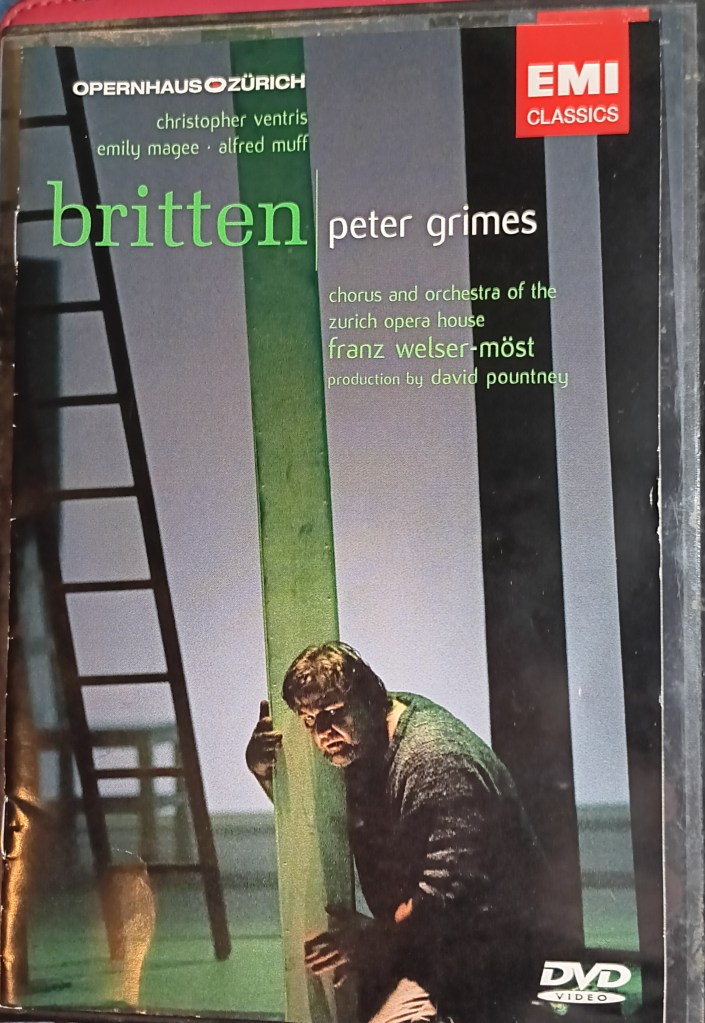

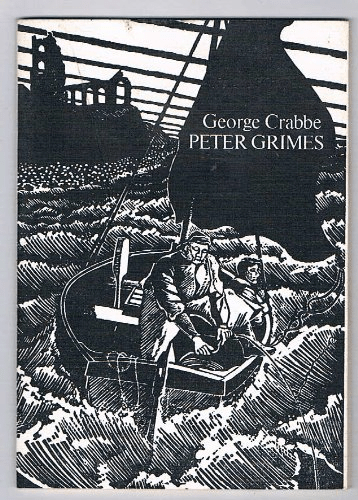

In March I will see, with dear friend Catherine, Opera North’s live production of Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes. This was to be my first live viewing. To prepare myself I watched a taped version of the opera last night in the David Pountney production from Zurich Opera House (conducted by Franz Welser-Möst) and had already re-read the Crabbe narrative poem – an extract named Letter XXII from his long descriptive and narrative series The Borough (available free to Kindle readers). Eric Roseberry’s 2007 assessment of the David Pountney production, in the DVD booklet, is that it de-emphasises the sea setting and motifs, other than as evocation of communal and individual feeling. It seems from the Opera North publicity that this company will balance symbolic with physical evocation of the sea. But of this in a later blog, or two.

The DVD booklet

About the Britten opera I have much more work to do, not least reading the libretto by Montagu Slater (I can’t read the music but can listen to it again). What is very clear however is that we are not dealing with versions of the same thing here. Britten’s opera involves women in Grimes’ life more and has less truck with what is the main thrust of Crabbe’s poem, at least as I see it – the tacit demonstration of the contradictions of patriarchy and ideologies created in the name of the Father.

But I think some commentators, although correct to see the Britten opera as a much richer (obviously so) work of art than Crabbe’s tale, to see that mainly demonstrated in the greater complexities of Britten’s Peter – a role first sung by his lover Peter Pears – than Crabbe’s Peter. In fact Crabbe’s poem requires two Peter Grimes’s: the father who opens the tale and the wayward and criminal son who is its sacrilegious subject, and the ‘impious’ reversal of the nature of a father’s authority over male youth. Committing himself after the death of old Peter Grimes, which when drunk he mourns, Peter takes to a life of exploiting the sea without recourse to measure, poaching and robbery. Here begins the attempt (half-hearted in my opinion but Crabbe is not a great poet) Crabbe makes to differentiate the ‘religiously sanctioned’ Old Peter from the impiety (acting against the principles of the love and name of Fathers) of the new one. The new Peter builds himself a remote new home to store ill-gotten gains:

He built a mud-wall’d hovel, where he kept

His various wealth, and there he oft-times slept;

But no success could please his cruel soul,

He wish’d for one to trouble and control;

He wanted some obedient boy to stand

And bear the blow of his outrageous hand;

And hoped to find in some propitious hour

A feeling creature subject to his power.

George Crabbe, Letter XXII 'Peter Grimes', line 51ff.

That ‘outrageous hand’ stands out with more than ‘rage’, not least because it has an analogue with his meek father who also has ‘feeling’ creatures ‘subject’ to his control:

His wife he cabin'd with him and his boy,

And seem'd that life laborious to enjoy:

George Crabbe, Letter XXII 'Peter Grimes', line 2f.

‘Of course we will be told that that ‘seem’d’, which seems to query the reality of the outward show of the old man’s feelings is really the outward sign of his inward grace of humility – a thing his son lacks, but not always the show thereof, for he shows enough humility to escape the censure of the borough, even for his vicious and loud abuse of the first orphan boy he takes under his uncertain ‘care’ but definite ‘control’. And though apparently meekly used, Old Grimes’ ‘hand’ is too a tool of coercion, but here perhaps validated coercion as he ‘took young Peter in his hand to pray‘. So validated is the patriarchal hand of coercion and control, it barely registers on the Borough community when Peter uses his ‘outrageous hand’ to chastise his first surreptitiously enslaved (the concept of slavery runs throughout) orphan boy, that it is expressed by the phrase of which Britten makes a fine choric song in the opera: “Grimes is at his exercise”. Hear the passage at length which ends with the lines I use in my title, and lists the kind of neglect that in notorious cases social workers have been accused of cases such as that of Baby P. (another Peter):

Some few in town observed in Peter’s trap

A boy, with jacket blue and woollen cap;

But none inquired how Peter used the rope,

Or what the bruise that made the stripling stoop;

None could the ridges on his back behold,

None sought him shiv’ring in the winter’s cold;

None put the question, - “Peter, dost thou give

The boy his food? - What, man! the lad must live:

Consider, Peter, let the child have bread,

He’ll serve the better if he’s stroked and fed.”

None reason’d thus - and some, on hearing cries,

Said calmly, “Grimes is at his exercise.”

Pinn’d, beaten, cold, pinch’d, threaten’d, and abused

- His efforts punish’d and his food refused,

- Awake tormented, - soon aroused from sleep,

- Struck if he wept, and yet compell’d to weep,

The trembling boy dropp’d down and strove to pray,

Received a blow, and trembling turn’d away,

Or sobb’d and hid his piteous face; - while he,

The savage master, grinn’d in horrid glee:

He’d now the power he ever loved to show,

A feeling being subject to his blow.

George Crabbe, Letter XXII 'Peter Grimes', line 67ff.

The first time the ‘trembling boy’, the first of three illegitimate children bought by Grimes from a shady London trader, is named is by Peter, after the boy’s suspicuous death. His name is ‘poor Sam’, but we are inclined to forget this detail given the adjective indicating sympathy is Peter’s also. That Peter’s exercise of ‘power and control’ is Satanic (enjoyed with ‘horrid glee’ – no seeming there) is obvious but not to the borough’s concensus view who do not question the necessity of binaries like master and slave, hard and soft, man and boy and their ability to mirror each other in relationships where power and control is vindicated.

What is Crabbe saying about patriarchal power and control here. Of course, the story obfuscates the fact of the analogy between the two Peter’s and their respective sources of authority over boys, each lying neatly inside acceptable patriarchal power relationships. The point has to be made in the poem constantly – less so by Britten who paradoxically makes the goal.of young Peter’s life marriage to a sensitive nuturing woman, Ellen Offord – that young Peter is a psychological anomaly, in Crabbe ‘s eyes; one who illustrates the right of men to take authority over unformed boys, and women but who takes that authority into realms of physical violence and verbal abuse. The anomaly in Crabbe’s young Peter is his refusal to connect a desire for power and control – which Crabbe suggests may be innate in men – to a supernatural validating authority: the submission of all men, even fathers, to God the Father. This is the very argument old Peter has with his son: one that generates age, time past, the Gospels message, and traditional as well as supernatural paternal love and power. IT is an argument narrated however from within the guilty memory of young Peter after Old Peter’s death

How he had oft the good old man reviled,

And never paid the duty of a child;

How, when the father in his Bible read,

He in contempt and anger left the shed:

“It is the word of life,” the parent cried;

- “This is the life itself,” the boy replied.

And while old Peter in amazement stood,

Gave the hot spirits to his boiling blood:

- How he, with oath and furious speech, began

To prove his freedom and assert the man;

And when the parent check’d his impious rage,

How he had cursed the tyranny of age,

- Nay, once had dealt the sacrilegious blow

On his bare head, and laid his parent low;

The verse here is meant to recall in Peter’s own mind the record of his past impiety, each episode beginning with the word, ‘How’. And yet, though apparently emotion recollection, its recollection is not only far from calm but reanimated in Peter’s present. The whole becomes a lesson for Peter’s claim that he is living life in the present, rather than hearing the record of past lives, in the Bible. Of course the ‘word of life’ must proceed from a past life of which it is a record and representation, whilst ‘life itself’ is conceived as of as an eternal present, even as it proceeds to the future, but the pressure of the verse, and the tenses of its verbs suggest that, in memory, Peter relives the past in the present (the verb ‘Gave’ is a continuing present tense, only starting in the past but repeated every time Peter drinks ‘hot spirits’ and in the same moment exemplifies his own, almost Satanic hot spirits – burning as if in his own Hell.

When Peter Grimes goes mad he sees visions of his Father returned with two boy spirits (why it is not three enumerating each of the boys Grimes has led to their death I do not know) and the liquids that are thrown about are both spirituous (in many ways but are eventually named hot-red liquor’ – possibly rum) and infernally hot – in part reflecting the circumnambient day, in part a vision of Hell. What emerges, especially in his last recounted vision is that he sees in his Father (whom he names now Father-foe) the ‘horrid’ and punishing glee of his own past behaviour to his kept boys but also attributes to the memory of his own Father, in his recalled boyhood as his Son, the same paternal malevolence he has enacted himself:

“In one fierce summer-day, when my poor brain

Was burning hot, and cruel was my pain,

Then came this father-foe, and there he stood

With his two boys again upon the flood:

There was more mischief in their eyes, more glee

In their pale faces, when they glared at me:

Still they did force me on the oar to rest,

And when they saw me fainting and oppress’d,

He with his hand, the old man, scoop’d the flood,

And there came flame about him mix’d with blood;

He bade me stoop and look upon the place,

Then flung the hot-red liquor in my face;

Burning it blazed, and then I roar’d for pain,

I thought the demons would have turn’d my brain.

“Still there they stood, and forced me to behold

A place of horrors - they can not be told -

Where the flood open’d, there I heard the shriek

Of tortured guilt - no earthly tongue can speak:

'All days alike! for ever!’ did they say,

‘And unremitted torments every day’ -

Yes, so they said” - But here he ceased and gazed

On all around, affrighten’d and amazed;.

Satanic vision or psychotic delusion, it represents the Father principle as a principle of Pain. And though this is a ‘madman’s’ speech are we correct in dismissing the first memory of his father in this confessional episodes – that which recalls an Old Peter Grimes with something other than seeming enjoyment in work but a real pleasure in humiliating and creating morbid fear in his ‘only Son’ (the inversion of the holy Father-Son relationship):

“’Twas one hot noon, all silent, still, serene,

No living being had I lately seen;

I paddled up and down and dipp’d my net,

But (such his pleasure) I could nothing get,

- A father’s pleasure, when his toil was done,

To plague and torture thus an only son!

We are told by Crabbe as narrator that this speech can be classified as ‘part confession and the rest defence, / A madman’s tale, with gleams of waking sense’. But what is mad, and therefore to be considered distorted and what is sense – something felt that recalls the microaggressions of a deeply repressed father who exercises his leisure on shaping his son’s expectations of his future on the impossibility of worldly success and of pleasure defined as sadistic torture of the weak. That is, after, the man Old Peter produces. And it is he who mentions the death of his wife, attributing it NOT to Peter but some other cause. Could that cause be the man who ‘cabin’d’ her with him. If this is an underlying true theme of the 1810 poem perhaps, since patriarchal abuse hides itself, except in agreed anomalies, we will never see the end of child abuse, even by 2210.

Thus in a tale that seems to hold the intention of discriminating good fathers from bad, I wonder if Crabbe opens up a critique of patriarchy that goes deeper, that focuses not on original sin, and anomalous sinners, but on the possibility that all Fathers embrace that name as an access to the real truth about sin – the deep desire, one that yields ‘;pleasure’ to hold power over, and control others, even to the point of elicited pain (somatic or psychological) – seeking such persons who are less resourced to challenge the power exerted over them. That would make of Crabbe a poet ready to countenance a challenge to the unequal distribution of power and equality – even to the extent that even ‘natural’ distinctions of strong and weak (such as that between most adults and children should be mitigated by social surveillance – the type the Borough refuses).

Some of this I saw in Britten too but the opera has many more strands, and a particular interest in seeming happy domesticity and the truth of queered sexualities, and the reason that in the society he paints these are commodified. But that is to look at after much more work. So in a work that looks to the past to predict the future, there is no clear certainty that the record of the past is ever clear enough to know with confidence what will come of the future. However, in a small way, I know I will use my future to learn more of the opera, and that is a joy – but only because of past work done and recollected.

With love

Steven xxxx

One thought on “‘He’d now the power he ever loved to show, / A feeling being subject to his blow.’ In 1810, a long time ago, a rhyming vicar, George Crabbe, could trace the origins of domestic abuse to the leeway given to men to ‘assert the man’ by the exercise of power and control. Why is it possible to see no end of this leeway in the future?”