To be good at judging the character of others clearly indicates some skill, knowledge and values (developed to a high standard) in the activity of ‘judging’ – and in this case of ‘judging character’). But what loaded words these are! Being, for instance, a ‘judgmental’ person is rarely seen as the quality of a good person, for judgement is often seen as an activity that takes precedence over other qualities that goodness also requires, such as empathy and the kind of altruism that moves beyond the boundaries of self to inhabit the skin of others, a quality that Atticus Finch recommends in To Kill a Mocking Bird(see my blog on this book here). Judgement is too often a matter of standards we like to think of as ‘objective’, even when they are not, as is self-evidently the case in the law courts of Alabama in that book when they attempt to adjudge the character of a Black male.

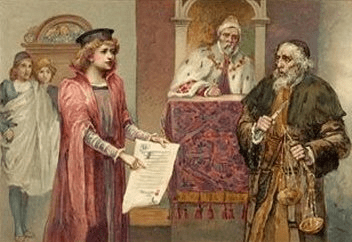

The simple point is stressed too in the most important speech in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice (Act IV Scene 1, line 190ff.), when Portia, dragged up as the male lawyer Balthazar speaks to Shylock in order to urge him to ‘show’ (as ‘earthly power doth then show likest God’s’) one of the most cherished values of Judaism, which broke the boundaries of patriarchal law to include in God’s relationship to his people the love of a mother, nurtured from the womb. Hear, for instance Dr. Eli Lizorkin-Eyzenberg, on the word in the Torah:

In biblical Hebrew, the word for “mercy” (רחם; racham) derives from the same three-letter root as the word for “womb” (רחם; rechem). This linguistic connection is not coincidental; it suggests that God’s mercy is akin to the protective, nurturing environment a baby experiences in its mother’s womb. To the ancient Israelites, mercy was not just an abstract emotion but a tangible act of divine shelter, care, and sustenance, mirroring the intimate bond between a mother and her unborn child.

Portia, a woman disguised as a man would then be (and actually on the Elizabethan stage a boy enacting a woman enacting a man, then is urging on Shylock to show or ‘give’ (for as I understand it the Torah always speaks of ‘giving’ (an active verb indeed) rather than ‘showing’ mercy, as in English translations, that which is the most androgynous of the emotions of God.

Hence though this speech tends to stress the power of the law as an instrument of judgement, it also emphasises the patriarchal ‘sceptred sway’ nature of the law, to induce the more passive qualities that cannot, like rain, do anything, but fall upon the land it blesses and fructifies.

The quality of mercy is not strained.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest:

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

’Tis mightiest in the mightiest; it becomes

The thronèd monarch better than his crown.

His scepter shows the force of temporal power,

The attribute to awe and majesty

Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;

But mercy is above this sceptered sway.

It is enthronèd in the hearts of kings;

It is an attribute to God Himself;

And earthly power doth then show likest God’s

When mercy seasons justice. Therefore, Jew,

Though justice be thy plea, consider this:

That in the course of justice none of us

Should see salvation. We do pray for mercy,

And that same prayer doth teach us all to render

The deeds of mercy. I have spoke thus much

To mitigate the justice of thy plea,

Which, if thou follow, this strict court of Venice

Must needs give sentence ’gainst the merchant there.

There is an important point here about ‘character’. We tend to think of character assessment as being based on what currently can be evidenced about the person whose character we judge – it works with the stuff of the present and past time and invokes the future only by projection of the judgement of the meaning of the past and present evidence onto the future. As a result judgements of character make no room for character development, even those those developments are emergent from the traits (and the words, actions and appearances that evidence them) for, as yet, they do not exist. They can only be nurtured as the womb nurtures the character of the baby out of love, at its best because in truth there is no inevitability about maternal love. My own feeling is that a good judge of character holds persons to their bond – the meanings that their behaviour in past and present binds them to – and does not giver an unstrained interpretation of what a person can become under the shelter of love rather than the precept of harsh interpretation based on hard evidence rather than soft potential.

Do I want to be a ‘good judge of character’? Let’s say no, for goats not sheep climb higher (and steeper) mountains!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx