I can’t remember exactly when it was, other than in the early years at grammar schoo! [1] Being a member of a drama group led to the volunteer who ran that group to enter her flock into a spoken English competition. We each had to choose a speech or poem to read. Most competitors went for something like Hamlet’s monologue on suicide, as I remember, or if not some anodyne poem that could not respond to nuance for it contained none – as, for instance, Thomas Hardy’s lyrics do. I should have chosen After A Journey really to wring the last ambiguity of its ‘unseen waters’ ejaculations’ or the range of disappointment in the thinness of the current object of desire and the frailty of the desire that follows it:

Hereto I come to interview a ghost;

Whither, O whither will its whim now draw me?

Up the cliff, down, till I'm lonely, lost,

And the unseen waters' ejaculations awe me.

Where you will next be there's no knowing,

Facing round about me everywhere,

.....

/

....

I see what you are doing: you are leading me on

To the spots we knew when we haunted here together,

The waterfall, above which the mist-bow shone

At the then fair hour in the then fair weather,

And the cave just under, with a voice still so hollow

That it seems to call out to me from forty years ago,

When you were all aglow,

And not the thin ghost that I now frailly follow!

I think at that time I was less aware that dramatic verse contains its complicated responses to a ‘listener’, even an imagined one, that causes the necessity of variance in the voice reading it dramatically, making it clear that though this speech is received by an audience indifferent to the poetic persona’s circumstances, it is as John Stuart Mill insisted as if speech ‘overheard’ that has an intention of being private. Here are the key words from Mill’s What is Poetry? (read the whole at this link):

Poetry and eloquence are both alike the expression or uttering forth of feeling. But if we may be excused the seeming affectation of the antithesis, we should say that eloquence is heard; poetry is overheard. Eloquence supposes an audience; the peculiarity of poetry appears to us to lie in the poet’s utter unconsciousness of a listener. Poetry is feeling confessing itself to itself, in moments of solitude, and bodying itself forth in symbols which are the nearest possible representations of the feeling in the exact shape in which it exists in the poet’s mind. Eloquence is feeling pouring itself forth to other minds, courting their sympathy, or endeavoring to influence their belief, or move them to passion or to action.

All poetry is of the nature of soliloquy. It may be said that poetry, which is printed on hot-pressed paper, and sold at a bookseller’s shop, is a soliloquy in full dress, and upon the stage. But there is nothing absurd in the idea of such a mode of soliloquizing. What we have said to ourselves, we may tell to others afterwards; what we have said or done in solitude, we may voluntarily reproduce when we know that other eyes are upon us. But no trace of consciousness that any eyes are upon us must be visible in the work itself. The actor knows that there is an audience present; but if he acts as though he knew it, he acts ill. A poet may write poetry with the intention of publishing it; he may write it even for the express purpose of being paid for it; that it should be poetry, being written under any such influences, is far less probable; not, however, impossible; but no otherwise possible than if he can succeed in excluding from his work every vestige of such lookings-forth into the outward and every-day world, and can express his feelings exactly as he has felt them in solitude, or as he feels that he should feel them, though they were to remain for ever unuttered. But when he turns round and addresses himself to another person; when the act of utterance is not itself the end, but a means to an end, – viz., by the feelings he himself expresses to work upon the feelings, or upon the belief or the will of another, – when the expression of his emotions, or of his thoughts, tinged by his emotions, is tinged also by that purpose, by that desire of making an impression upon another mind, then it ceases to be poetry, and becomes eloquence.

It was later my belief that a great poet like Robert Browning deliberately undermined Mill’s critical view, even in calling his poems ‘Dramatic Lyrics‘ or ‘dramatic monologues’. In them there is clearly a listener, though usually one impervious to the speaker’s meaning, either because of their absorption in their own affairs like the wife, Lucrezia, in Andrea del Sarto, or because they are actually dead, as in Evelyn Hope, sometimes by the hand of the speaker previously, as in Porphyria’s Lover. Clearly, Mill’s definition would exclude these poems, perhaps even some of the greatest like The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church. But it would exclude too all of Shakespeare’s dramatic verse, except of course To Be or Not To Be.

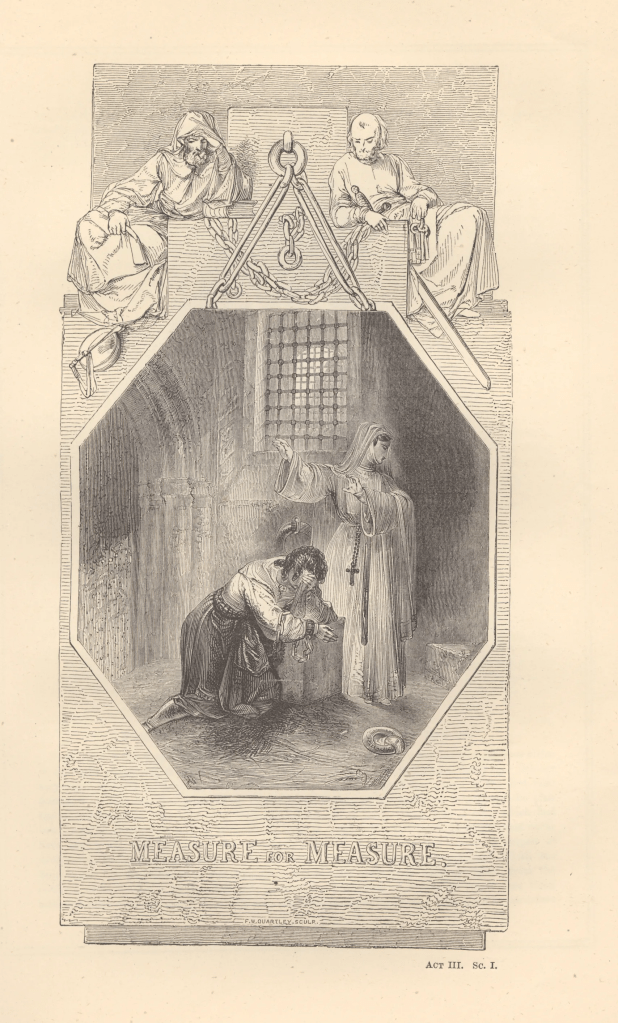

Now none of those considerations went through my head, except that I felt there was a particular quality to a speech ztartin ‘Ay, but to die …’ by Claudio in Shakespeare’ Measure for Measure that clearly was personal and addressed himself mainly and also strongly rhetorically eloquent. It addressed two audiences other than himself.. First,a critical audience awaiting a new set piece from Shakespeare’s facility with blank verse, but second, his sister, Isabella, who might be persuaded that her brother’s fear of death was lesser than her own fear of losing her virginity in exchange for his life, to the deputy Angelo.

Here is how the scene tells the tale:

ISABELLA .....

Dost thou think, Claudio,

If I would yield him my virginity

Thou mightst be freed?

CLAUDIO O heavens, it cannot be!

ISABELLA

Yes, he would give ’t thee; from this rank offense,

So to offend him still. This night’s the time

That I should do what I abhor to name,

Or else thou diest tomorrow.

CLAUDIO Thou shalt not do ’t.

ISABELLA O, were it but my life,

I’d throw it down for your deliverance

As frankly as a pin.

CLAUDIO Thanks, dear Isabel.

ISABELLA

Be ready, Claudio, for your death tomorrow.

CLAUDIO Yes. Has he affections in him

That thus can make him bite the law by th’ nose,

When he would force it? Sure it is no sin,

Or of the deadly seven it is the least.

ISABELLA Which is the least?

CLAUDIO

If it were damnable, he being so wise,

Why would he for the momentary trick

Be perdurably fined? O, Isabel—

ISABELLA

What says my brother?

CLAUDIO Death is a fearful thing.

ISABELLA And shamèd life a hateful.

CLAUDIO

Ay, but to die, and go we know not where,

To lie in cold obstruction and to rot,

This sensible warm motion to become

A kneaded clod; and the delighted spirit

To bathe in fiery floods, or to reside

In thrilling region of thick-ribbèd ice,

To be imprisoned in the viewless winds

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendent world; or to be worse than worst

Of those that lawless and incertain thought

Imagine howling—’tis too horrible.

The weariest and most loathèd worldly life

That age, ache, penury, and imprisonment

Can lay on nature is a paradise

To what we fear of death.

ISABELLA Alas, alas!

CLAUDIO Sweet sister, let me live.

What sin you do to save a brother’s life,

Nature dispenses with the deed so far

That it becomes a virtue.

ISABELLA O, you beast!

O faithless coward, O dishonest wretch,

Wilt thou be made a man out of my vice?

Is ’t not a kind of incest to take life

From thine own sister’s shame? What should I think?

Heaven shield my mother played my father fair,

For such a warpèd slip of wilderness

Ne’er issued from his blood. Take my defiance;

Die, perish. Might but my bending down

Reprieve thee from thy fate, it should proceed.

I’ll pray a thousand prayers for thy death,

No word to save thee.

CLAUDIO Nay, hear me, Isabel—

ISABELLA O, fie, fie, fie!

Thy sin’s not accidental, but a trade.

Mercy to thee would prove itself a bawd.

’Tis best that thou diest quickly.

CLAUDIO O, hear me, Isabella—

Claudio is desperate to be ‘heard’ (‘Nay, hear me’) by his sister, but what he wants her to hear is not just, as she seems to hear, his readiness to trade his sister’s sexual independence for his life, but the depth of his fear of giving up living and accepting that death may not be the end of his suffering, but perhaps the beginning of worse suffering. Of course, it reprises Hamlet’s thoughts:

Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovere'd country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

But Hamlet here is more eloquent than poetic, to use John Stuart Mill’s terms. He uses impersonal examples of what life is for many bufor him, and the phase ‘puzzles the will’ stands remote from overt emotion, leaning into the ‘discourse of reason’, refined in Wittenberg. Not so Claudio, where the emotion is felt viscerally and performed thus in tje verse. Let’s have the speech as I read it, apparently divorced gron the narrative drama:

Ay, but to die, and go we know not where,

To lie in cold obstruction and to rot,

This sensible warm motion to become

A kneaded clod; and the delighted spirit

To bathe in fiery floods, or to reside

In thrilling region of thick-ribbèd ice,

To be imprisoned in the viewless winds

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendent world; or to be worse than worst

Of those that lawless and incertain thought

Imagine howling—’tis too horrible.

The weariest and most loathèd worldly life

That age, ache, penury, and imprisonment

Can lay on nature is a paradise

To what we fear of death.

I say ‘apparently ‘ divorced, for it can not be such in performance. Hamlet’s argument about life as wearidome used he, ‘would gardens bear’, unaccomodated man compared to Hamlet’s court clothing and idle life. Claudio speaks in prison and it is important then that when he uses prison as a metaphor, it is also realised in the chains we see that bind him and the doors that lock him in, charged with crime bearing a death sentence. Yet those external prisons he imagines are invisible ones too, ‘viewless winds’ more felt in their ‘restless violence’ u on thdvreceptors of blind sense than seen.

Claudio’s imagery moves within to areas of experience undetectable externally, and difficult to use to argue a case that is eloquent, for it is too sensuous, bearing material pressure on the nerves. When I read it as a boy, I remember words that had to feel solid in the saying, even when theze words were of Latin origin and usually considered as of abstract quality, like ‘obstruction’. Etymonline.com argues that the word was used of physical obstruction in a street or passage, mainy of which must have been experienced in Renaissance London and only used figuratively in the 1650s, but presumably they mean in common parlance:

obstruction (n.) : “action of blocking up a way or passage, act of impeding passage or movement; fact of being obstructed,” 1530s, from Latin obstructionem (nominative obstructio) “an obstruction, barrier, a building up,” noun of action from past-participle stem of obstruere “build up, block, block up, build against, stop, bar, hinder,” from ob “in front of, in the way of” (see ob-) + struere “to pile, build” (from PIE *streu-, extended form of root *stere- “to spread”). Figurative use is by 1650s.

Commonly, the writing of Measure for Measure is thought to be 1603 – 1604, but yet what is characteristic of the use of obstruction here is not that it represents the active process of obstruction but the organic material used in the construction, stuff that can ‘rot’ – perhaps the block caused by refuse, or offal, even excrement in the passage ways of the body’s digestive system. That it is ‘cold’ is of the nature of longer lying refuse. The effect is visceral rather than cerebral. That coldness is soon supplanted metaphorically by the process of cooling that turned the body cold: ‘warm motion’to become a clod, whose absence, or even negation, of heating properties to the hand that kneads it shows its difference from life-giving bread.

The body exists as something acted upon by processes of graduated deficit – ageing, poverty, and, of course, incarceration in a cold cell. We feel Claudio’s despair and though we know he is over- pressing his argument to Isabella, we know this is no mere eloquence just addressed to her, or an exemplary of fine verse for a gentle person to write in their commonplace handbook. It is self speaking to self about the body and its refusal to accept either an end OR a new and endless beginning in which all the body produces for eternity is imagined ‘howling’. The imagined type of eternal howling is even more visceral than its reality, which robs one of consciousness of itself: thus men invented Hell to scare the body.

When I chose that speech in preference to others’ choosing one ‘To Be or Not To Be’ speech after another, i was not quite aware of its pertinent to my embodied fears, like those of Claudio. I just knew this was poetry in the way the more famous Hamlet speech is not. That i might breathe in fire or get constricted in ‘thick-ribbed ice’ was matter to feed a far from abstracted sense of what poetry is. It was a thing that spoke to many people at different levels in dramatic verse. My adjudicator said he thought my rendition was passionate but surely I knew it had to be read with a voiced accent on the ‘e’ of ‘ribbed’. He was right. What I needed to know however is not about Shakespearean pronunciation but that the poetry demand those ribs be realised as a cage which ribbed- BED does but ribbed does not.

So, that was my earliest public speech. Bye for now.

Love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] There is now a memory-jogged addendum to this post. See it at this link.

One thought on “My memory of choosing a speech to perform in young teenage in a spoken English talent competition”