Most of us favour only one animal – humans, and pretend to enjoy instead the slavery of the animals we willingly harm and subjugate to our will in order to feed, in every sense, our needs! Why are we so wrong?

We all think we have a favourite animal and assume when we say this that this animal is favoured by us, it is chosen solely on the basis of the superior choice enabled by being a human, an animal that often claims not to be such but a being who is defined as the very binary opposite of an ‘animal’. We deserve respect more, we assume, because we possesses skills, like articulatable and demonstrable cognition and emotion that we assume to be absent in them, usually quite against the extant non-linguistic psychological evidence, and for animal lovers, ordinary common sense. We value ourselves, though, against animals. People often say in conversation: ‘they treat animals better’, a very dubious statement. Shakespeare, who always refines common thinking into the highest poetic form, has Lear mouth the same to his daughters when they ask him why he needs an independent retinue to serve him in their well servant-populated castles:

O, reason not the need! Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous.

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man’s life is cheap as beast’s. Thou art a lady;

If only to go warm were gorgeous,

Why, nature needs not what thou gorgeous wear’st,

Which scarcely keeps thee warm.

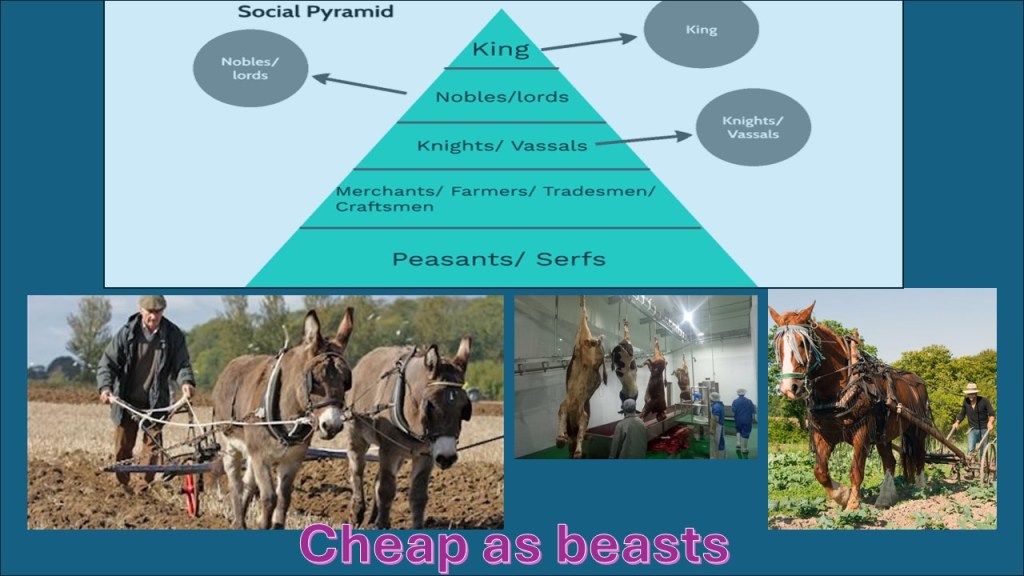

We ought not still be asking students to look for animal imagery in poetry, for in this case, animals are used discursively to create a symbolic hierarchy of value, that runs from the wealthy – kings and ladies (ladies being a class term), down to the ‘basest beggar, except that there is a base even below the lowliest beggar – animals. Animals are the living beings of nature, Lear implies, and humans are worth more than nature precisely because they possess that which in nature is superfluous. It all comes down to this. In the end, we humans are deserving of more respect and moral value than no-human animals because we can, unlike them, possess things we do not need and use them as a measure of our power. It is reducible to exchange value – the value of man and beast are compared in terms of their relative cost, from dear to cheap.

Shakespeare has Lear dismantle that hierarchy slowly. In a storm on a heath he finds what he believes to be an example of the ‘basest beggar’, Poor Tom, a madman, who is really the Duke of Gloucester’s son, Edgar in disguise. Suddenly he realises that there is a level of humanity that is not ‘in the poorest thing superfluous’. Only the entitled rich posses the ‘superflux’ of wealth and social value and might well learn from homeless humans, once they are exposed to the raging elements within and without , what it means to posses anything of value or being seen as being of value. Lear becomes a Leveller (before their time of prominence in British socio-political life), looking for a just social order where religion demands social and economic justice:

Poor naked wretches, wheresoe’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this. Take physic, pomp.

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou may’st shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just.

It is then only a matter of time before Lear sees that the very society he ruled over – the one ruled over by Elizabeth I and James I too some time later – is one wherein human life is already cheap as beasts in some extremities of mind, body and social standing. But his formulation of this is one of Shakespeare’s great prose triumphs.

Thou wert better in a grave than to answer with thy uncovered body this extremity of the skies.—Is man no more than this? Consider him well.—Thou ow’st the worm no silk, the beast no hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no perfume. Ha, here’s three on ’s are sophisticated. Thou art the thing itself; unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art. Off, off, you lendings!

Come, unbutton here. [Tearing off his clothes.]

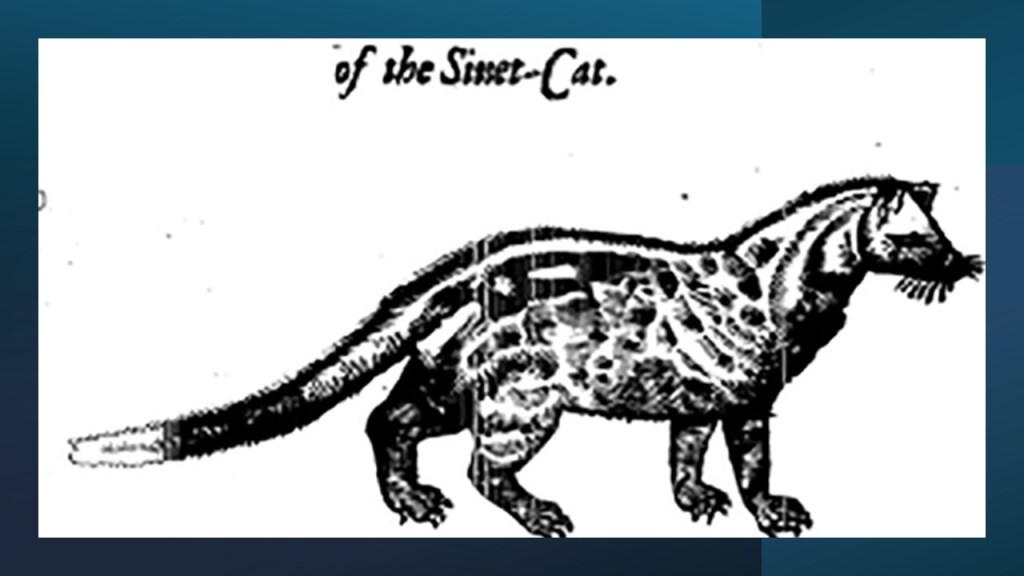

Poor Tom, as Lear sees Edgar, is the example of a man ‘unaccomodated’; not only without house or permanent shelter but also clothing, either ‘gorgeous’, like Goneril and Regan wear, or ‘the poorest thing’. To be unaccomodated is to have no things at all – no commodities to either own or to buy and sell. But what makes this speech the most radical in literature is that it realises that Tom – and potentially all humans, may have less than what an animal in nature has, which nevertheless humans have stolen from them: the silk from a silk worm, the hide of cattle, wool from sheep, or perfume from cats. Of course the last is a puzzle to most of us until we learn that the musk perfume of the African civet cat was a luxury that Elizabeth I sought openly, inviting Italian traders to Southampton to stock the rich of England with it:

And then go back to Shakespeare’s mercantile metaphors in his verbs applied to human relation to animals language: ‘Thou ow’st the worm no silk, the beast no hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no perfume’. Such a metaphor works precisely because we know humans believe that they ‘owe’ nothing (or are in debt to) animals at all. We take the animal product, oft along with the life of the animal – especially the unseen civet cat, in order to hide the disgusting body odours of Elizabethan human bodies, under their over-superfluous clothing – which are again the commodified lives of animals. This is as radical as even J.M. Coetzee or the anti-vivisectionist Lewis Carroll get on this theme (see my blog here).

I love my pet dog, Baz – not yet as much as the one I lost – but there is no doub that he too entered the world of commodification to be a thing for humans to own and favour even as much as dogs are used in the food market in some cultures, even though I tried to wriggle out of that moral conundrum with Daisy (see the offending blog on Daisy here).But here is Baz waiting for his walk whilst I finish this:

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx