‘Putting off’ is a relative thing. It is as likely that we ‘put off’ even things we know we will do, either because we must or because we are driven by the pain that reality brings as much as by the pleasure of fantasy in the yet unrealised event in the future. This blog tests that idea against one of my birthday treats this year, already dealt with in past blogs – link to them in the table below detailing those delights :

| Tuesday 21st October | Wednesday 22nd October |

| 10.30 a.m. Lee Miller’s Surrealist Photography at Tate Britain, Millbank: THIS BLOG PREPARES. Followed by river boat to | 10.30 a.m. Gilbert and George retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank |

| 2.00 p.m. Theatre Picasso at Tate Modern 7.30 p.m Punch Play by James Graham, Apollo Theatre | 2.30 p.m. The Bacchae A new play by Nima Taleghani after Euripides, The National Theatre. |

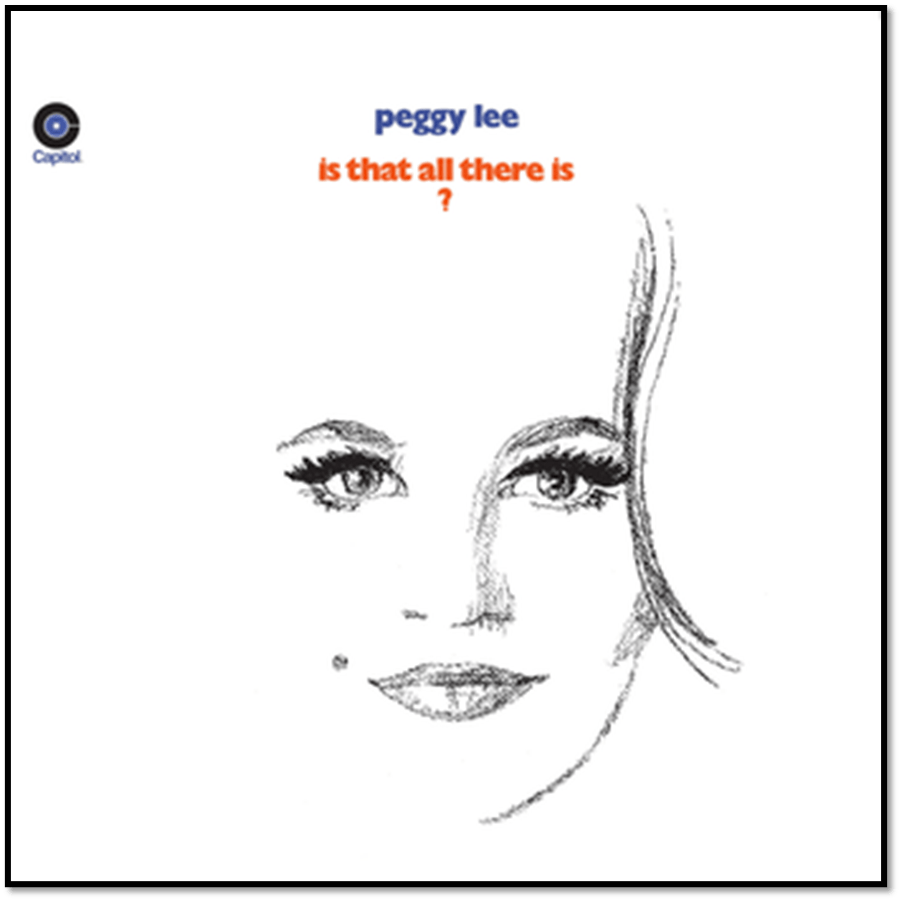

But Lee Miller. Now there is an issue, where more than usual, I feel that I am shoring myself – ‘putting off’ if you like – the possibility of disappointment. Before I start though, I want to share one of the most glorious pieces of art I know about this very feeling, Peggy Lee’s renderings (I saw it at her last concert in the UK in the then Festival Hall): Is That All There Is? Here is the face, then the lyrics:

I remember when I was a very little girl

Our house caught on fire

I'll never forget the look on my father's face

As he gathered me up in his arms

And raced through the burning building onto the pavement

And I stood there shivering in my pajamas

And watched the whole world go up in flames

And when it was all over I said to myself

"Is that all there is to a fire?"

[Chorus]

Is that all there is?

Is that all there is?

If that's all there is my friends, then let's keep dancing

Let's break out the booze and have a ball

If that's all there is

And when I was 12 years old

My daddy took me to the circus,

The greatest show on earth

There were clowns and elephants, dancing bears

And a beautiful lady in pink tights flew high above our heads

As I sat there watching

I had the feeling that something was missing

I don't know what

When it was all over I said to myself

"Is that all there is to the circus?"

[Chorus]

Is that all there is?

Is that all there is?

If that's all there is my friends, then let's keep dancing

Let's break out the booze and have a ball

If that's all there is

And then I fell in love

With the most wonderful boy in the world

We'd take long walks down by the river

Or just sit for hours gazing into each other's eyes

We were so very much in love

Then one day he went away

And I thought I'd die, but I didn't

And when I didn't, I said to myself

"Is that all there is to love?"

Is that all there is? is that all there is?

If that's all there is my friends, then let's keep... (i.e: [Chorus])

I know what you must be saying to yourselves

"If that's the way she feels about it, why doesn't she just end it all?"

Oh, no. Not me

I'm not ready for that final disappointment

Cause I know just as well as I'm standing here talking to you

And when that final moment comes and I'm breathing my last breath,

I'll be saying to myself

[Chorus]

Is that all there is?

Is that all there is?

If that's all there is my friends, then let's keep dancing

Let's break out the booze and have a ball

If that's all there is

There are slim chances of me these days ‘breaking out the booze’ or, frankly, ‘having a ball’ to fend off the effects of disappointment. All I have is anticipation. However, some information comes first. When I first thought of writing up this exhibition, by the way, and before I found the gift-horse in the prompt question it now appears under, (like all gift-horses since the Trojan one ambivalent and hiding something) I titled my piece thus:

Is there any real chance of looking back on the work of a photographer ‘in the flesh’ at an exhibition? This blog reveals, in part, my anticipations (both fearful and expectantly delightful) of seeing the ‘long-awaited’ Lee Miller exhibition at Tate Britain on the 22nd October 2025.

So here are my anticipations:

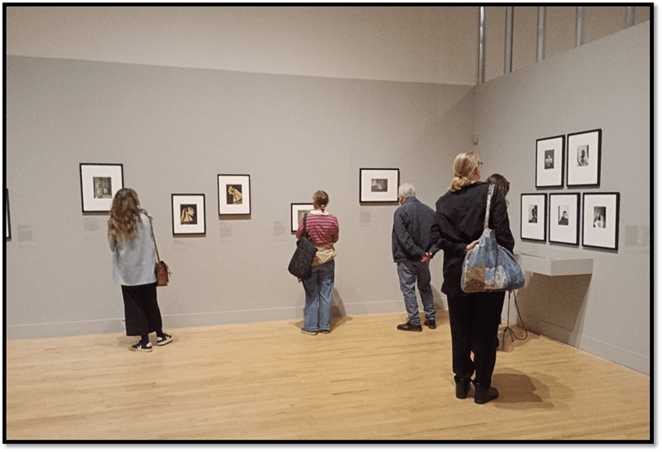

There is something like the alarming fear of disappointment in that title that was triggered by the photograph of visitors to the exhibition. I found the same feelings about the photograph in Sarah Kent’s rather grim survey of it in her review for The Arts Desk

So does exhibition bring Lee Miller and her remarkable career into sharper focus? Not really. Scale is one problem. Many of the prints are tiny, and peering at row after row of small images is tiring and soporific. One needs an occasional change of pace, and a few enlargements would alleviate the problem. Other prints are lacking in contrast and clarity; the rich tonality of (a) 1941 photo of Elizabeth Cowell …, for instance, came to light only when I saw it on screen.[1]

Does size and variation of the standard of that size matter – I have often felt as Kent seems to do here in exhibitions of photography – rather unmoved and unexcited about what I was seeing, especially now, given that I have viewed them in excellent reproductions in the exhibition catalogue, a fine addition to the art history and critique of Lee Miller.

Hilary Floe with Saskia Flower (Ed.) [2025: 144 – 161} ‘Lee Miller’ London, Tate Publishing

But when I turn to Kent’s summary again I wonder at the hubris of judging some of the photographs as ‘lacking in contrast and clarity’, given that the curators would be driven by many reasons to seek reproductions that in some way resemble a belief about Miller’s likely intentions, and that other means of reproduction , such as on a still or moving screen, import other qualities of the medium that Miller may never have wanted (not that we’d know). So I wonder if here Kent’s disappointment does not have some of the obsessive quality of that in the Peggy Lee song. Moreover, Kent’s view of this may be caused by her feelings on the day or other accidental factors, for other witnesses do not concur at all: one example being India Block in The Standard, who says:

… book out an hour or two of your time and immerse yourself in this sharply curated exhibition, which tells Miller’s story through her own impeccable eye. The exhibition’s careful pacing gives the audience space to discover for themselves what a consummate talent Miller was, alongside putting herself at the cutting edge of culture and history for decades. …. / …. And yes, the infamous portrait of her washing off the filth of Dachau in Hitler’s own bathtub is there — as you’ve never encountered it before.

See! I say to myself – ‘sharply curated’ and with ‘careful pacing’ – and look again at the photograph of the show and see – however small the pictures, they are grouped in asymmetrical manner that must change how one paces the exhibition and give rise to different kinds of reflection as that happens. So I am still left in hope. However Block can take away with one hand what she gives in the other, for her view is that the exhibition ought to be seen by people innocent of ideas about Lee Miller’s life, or as she puts it:

Lee Miller’s life was truly stranger than fiction, but I would urge you not to brush up on the astounding details before this blockbuster retrospective at Tate Britain. And try to push Kate Winslet’s (admittedly wonderful) performance in the 2023 film Lee from your mind. [2]

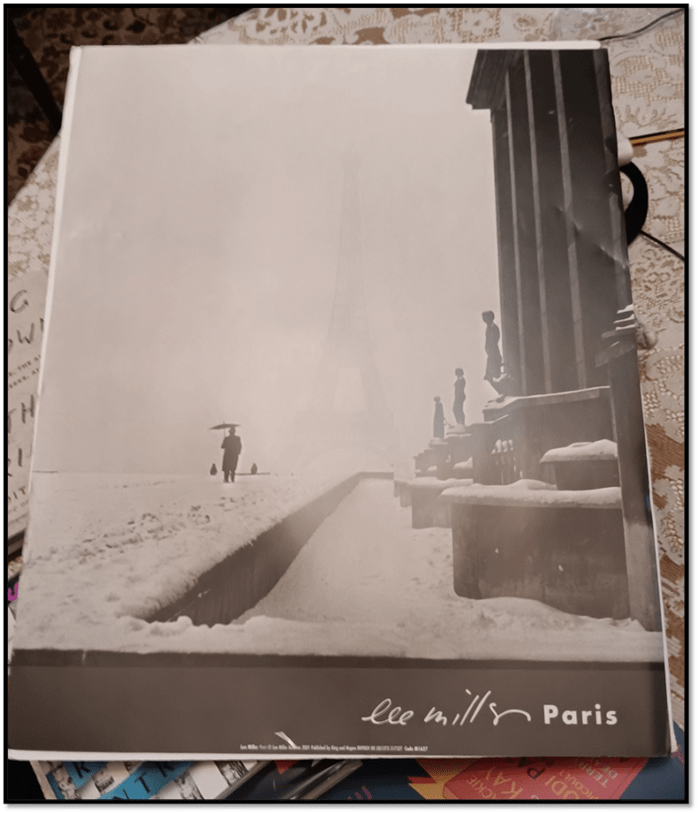

Again I am in the doldrums because I have shown interest in Lee Miller for many years, although largely in terms of her photographic technique based on once possessing a print of a photograph showing, surreally enough for later consideration, the ghost of the Eiffel Tower in a Paris fog (not in the exhibition or seen elsewhere in print) which I have now passed onto a dear friend as a birthday present, and is hopefully (should I have misjudged his taste) not in a bin now.

Moreover, I have a mall collection of books (only two to be frank) as well as Anthony Penrose’s (her son) biography on Kindle. The little first edition of Grim Glory, of war-time London, is actually featured in a section of the show named ‘Grim Glory’, and it will be instructive to see how the curators select, organise and size the photographs often :

And worse still I have blogged on Miller after seeing the film Block asks me to forget, which I called: A great film worthy of the inimitable Lee Miller: ‘Lee’ seen on Tuesday 17th September 2024, (available at this link).[3] Am I still doomed for ‘final disappointment’? Given that I always read up before exhibitions I can only see. Sometime I think the interest of a story or of an oeuvre is heightened because you have heard diverse voices discourse differently upon it, for you can assess where you stand for yourself.

And moreover there are bound to be items here I have not seen before. Annabel Downes writing in Another Magazine precisely says that:

One of the joys of a retrospective is finding artworks that were never destined for the spotlight, instead remaining buried in the archive. On view at Tate Britain’s new Lee Miller exhibition is a pair of near-identical photographs, each no bigger than an iPod Nano, depicting a severed breast laid out on a plate, flanked by a knife and fork. They were dated from around 1930, when a young Miller had been working as Man Ray’s apprentice in Paris. In need of some extra money, she began photographing surgeries at the Sorbonne Medical School and, after witnessing one radical mastectomy, asked the surgeon if she could take the removed breast back to her studio at French Vogue. She had apparently seasoned it with salt and pepper for the photograph, before Vogue’s editor-in-chief, Michel de Brunhoff, in a fit of disgust, threw both Lee and the breast out. Absurd, if a little gross, these tiny two photographs have been pulled from the archives for the first time in a retrospective of 230 odd works that chart the restless, shape-shifting life of the photographer Lee Miller.

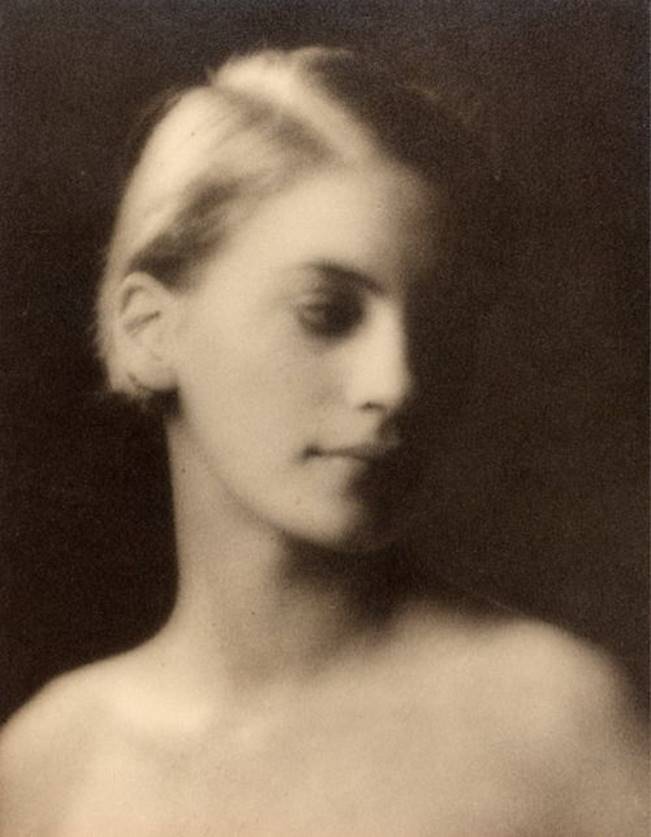

True!: I have now seen reproductions of these breast pictures in the catalogue and can’t, unfortunately, unsee them. Moreover, I cannot imagine any ‘joy’ in seeing them again (nor of sharing a peek of them here), except that Lee Miller’s object here is clearly one – even down to the culinary seasoning of the breasts – that digs down below the surface of assumed realities, so the breasts that are offered up as an example of visual beauty or the object of sexual perversion (in some of Man Ray’s work), can be seen as the ‘meat’ they are to some men’s appetites; exposing the male hegemony of the French Surrealist movement to some ironic critique but also the function of photography – an interest in which arose from Lee’s father who used her as his nude model, as well as her experience of modelling – though not nude – for Edward Steichen, Cecil Beaton (an indirect admiration there), her own narcissistic gaze and, in the first piece in the exhibition, Arnold Genthe, whose work mystifies her beauty in the gaze of man who wants to think himself (whatever the truth for the photo only just cuts out what might be naked breasts) attuned to mystic visual experience.

But the real joy of the new lies sometimes in those other areas of newness the exhibition picks out also mentioned by Downes as pieces, attention to whom ‘has slipped from view’. In these the attempt to go beneath the superficial play of ideas and irony in art photography seems to have come from the desire to free herself from her role as a ‘wife’ of a man who had everything in Egypt, to which he had taken her to reside, and explore the strange ways in which previously unseen worlds present themselves as unexplored spaces, and then to allow her to reflect on what ‘space’ actually meant for a visual artist. Downes says:

To fend off the boredom creeping into her life there (“I sit around and read rotten detective stories instead of writing to you,” she wrote to her brother Erik in one letter dated 1935), she began organising excursions into the desert; travelling to the monasteries of Saint Antonius and Saint Paul on the Red Sea hinterland. Those trips pulled her back to the camera – something she had a habit of abandoning, only then to fall back in love with.

One of the best known works from this period is Portrait of Space Al Bulyaweb, near Siwa, Egypt (1937), taken inside a remote traveller’s rest stop en route to Siwa in Egypt’s Western Desert. The torn mesh in the foreground opens onto a barren, rocky plateau beyond; the image reads as both an expression of isolation and, perhaps, a longing to break out of it. Elsewhere, her surrealist eye roams the landscape, coaxing the strange out of the ordinary. The domes of the Deir El-Soriani Monastery in Wadi Natrun swell into the curving female forms of her Man Ray days; …,.[4]

Downes’ characterisation of Portrait of Space is one that stresses emotion and vague dissatisfied ambition but doesn’t take the piece seriously as art, which the exhibition intends you to do, including a fine essay by the French intellectual Damarice Amao, which argues that Egyptian travel during a period usually thought of as aesthetically fallow for Miller, was far from such and was far too from being motivated only by housewifely boredom, in fact became a self-motivated and self-planned ‘re-education of the gaze’ of Miller as an artist in which she ‘tried out radical points of view, … – close-up, off-centre, tilted views, mise en abyme’ that ‘transformed photography into a dynamic experience firmly set in a careful observation of reality, at the limits of surrealism’.[5] And then look back on the work mentioned by Downes, which alone of the work from this period is already well known:

Lee Miller, Portrait of Space, Al Bulwayeb near Siwa 1937© Lee Miller Archives, England 2025

This work feels to me almost too perfect a portrait of space as a concept divided between opacity and transparency, frame, foreground and background, a mirrored inner framings of different kinds, and almost perfect repetitions of different kinds and levels of depth and surface . It is like a wordless essay on the aesthetics of photographic creativity and a true instance of an artist working on ‘complex representational strategies’, in Hilary Floe’s terms before our very eyes and forcing those eyes to collaborate in its effects.[6]

The catalogue is full of brilliance that seems missed by some critics, but especially Sarah Kent, who has no time for theory. She says:

Among her friends were many Surrealists, and the exhibition curators are keen to claim her as one of them. But I see no reason to pigeonhole her like this, since her keen eye for the comedy or pathos of random occurrences remains fresh to this day. Surrealist imagery, on the other hand, often feels dated and contrived.

And again later:

And in my view, emphasising her role as an artist and labelling her a Surrealist while glossing over her war reportage – which was so singular and so important – does her an injustice. Technically and creatively, she was innovative in every way. Her special skill, though, was the ability to respond to the needs of the moment. …

Ironically, this may be the very reason she slips from your grasp when you try to pin her down and categorise her as a fashion photographer, an artist or a war reporter. She is so much more than any of these. She is plural.

Correct or not about Cocteau, this remarks really oversimplify the very best of surrealist achievements, about which I am no more a fan than Kent. It also becomes reductive about why there is a turn to theory (to find out how and why the strategies of representation of space and time should concern us whether used in reportage on real world issues or in pure art, if such a thing as the latter exists. Reflexive concern about how we represent things are as important in the former as the latter, if we are not to turn war reporting merely into fact and sentiment somehow put together for the purposes of propaganda. Kent does get a picture like Portrait of Space, but denudes it of theory on which Miller as an artist worked to become superior often and an equal sometimes of surrealist male artists. It reduces her in her context as an artist but also as a woman, who was much more than just a clever pragmatist – though she was that too. Here’s Kent’s summary of Portrait of Space 1937. She says:

features a view of the desert framed by a torn mosquito screen on which hangs a mirror reflecting nothing but emptiness. Her pictures are characterised by unusual angles, viewpoints or framing that make the mundane seem strange.[7]

Why is this just strange queered art by a talented individual woman and not just more intelligently theoretical and beyond its time than Cocteau. After all, she worked in Egypt with surrealists often forgotten by colonial art history. Downes is much more at ease with fabulously intelligent art-theoretical female artists. She shows in her review, as does the catalogue that surrealist strategies ran through the fashion photography in war-time London and even the concentration camp photography, saying of the latter:

There’s the caved-in face of an SS guard, a train packed with corpses, two Allied soldiers peering in, and a cropped image of a pair of legs – a survivor – clad in the striped uniforms forced on prisoners. Standing in front of these photographs, you feel a world away from the Man Ray studio experiments and glossy Vogue couture of her early rolls of film. And yet, the same fearlessness is there; the instinct to cross whatever frontier she had to in order to reveal what others simply couldn’t see. Miller’s surrealist eye from those early days never left; she simply carried it to the darkest edge of reality, so others were made to see it too.[8]

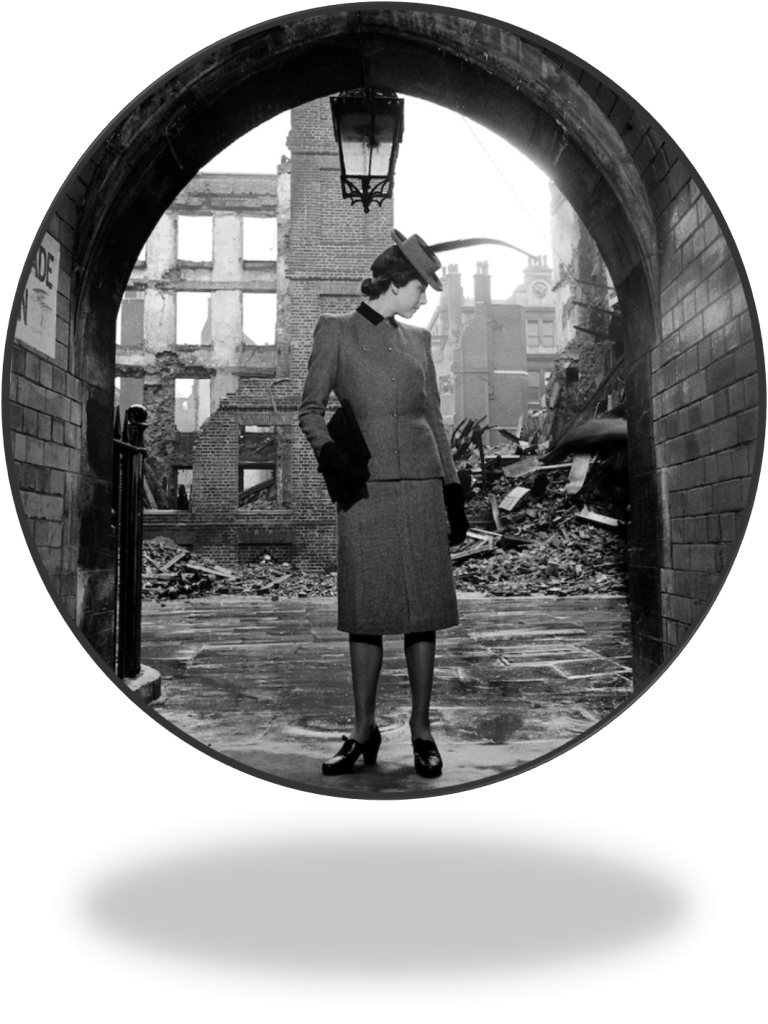

There is no fear here of doing something male intellectuals could not do quite as well – make their strategies of representation matter. And Downes does help me to look at those painful images she mentions. And this is not to the detriment of seeing Miller as first and foremost a feminist, working to show women as constantly having to work in representational frameworks imposed on them – as models do – but as models or in becoming the observing eye themselves being intent on renewing the vision of womanhood and femininity. On the same issue Block says that Miller as a fashion photographer: ‘… creates wildly surreal images of smartly tailored models against bombed-out urban landscapes’.[9]

In this image a woman is still framed but in a context in which her interior light in potential is highlighted and her face bodied out in an illusion of three dimensions to stop it being merely a model for cosmetics. Yet Lee Miller allowed men to feel they were the driving force in representational innovations as in the re-invention of ‘solarisation’ with Man Ray. Block writes thus:

Working in tandem with Ray she developed “solarisation”, a technique to manipulate images and create a halo effect. Later on, living in Cairo and with no dark room to hand, she learned to frame her compositions with exacting precision and used local Kodak print shops. On assignment as a war correspondent, she printed by torchlight in a bombed-out camera shop.[10]

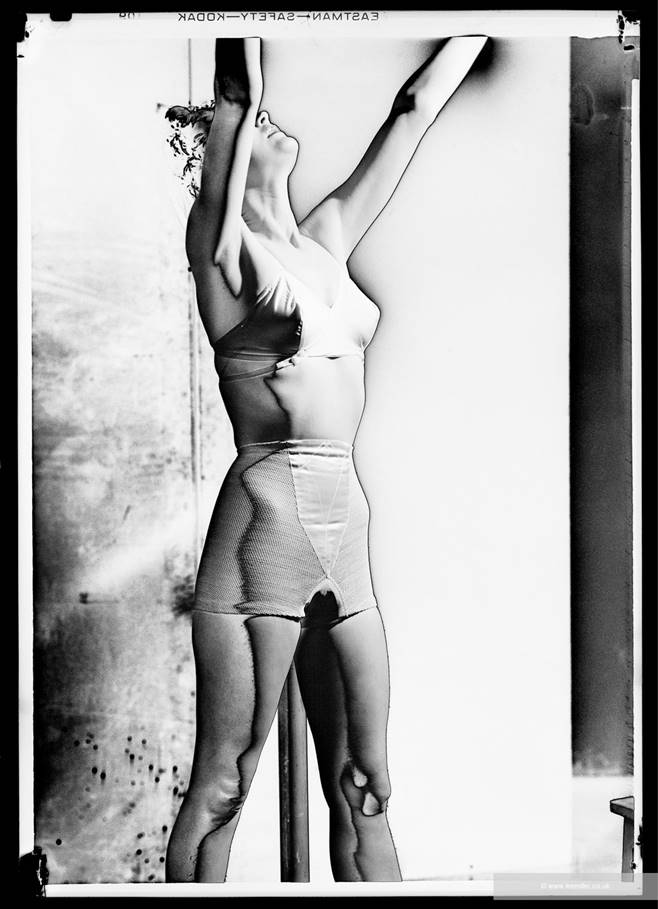

But when Miller used solarisation, it was to the heightening of the significance of female bodies beyond norms, as something almost world-historical in the corset advertisement shot below. In it the woman’s gaze is not turned outward but upward and obscured by her triumphant arms. Her whole body is transformed into something resistant rather than inviting but wonderfully beautiful Deborah Levy in na essay in the catalogue says Miller often must have mused of the women she and others were made to be: ‘What is she going to do with her beauty’. (According to Deborah Levy she steps from being ‘muse’ and ‘model’ to self-sustaining artist.[11] I agree. In the photograph above and below is another wordless answer to Levy’s posed question:

Lee Miller, Solarised Corsetry 1942© Lee Miller Archives, England 2025

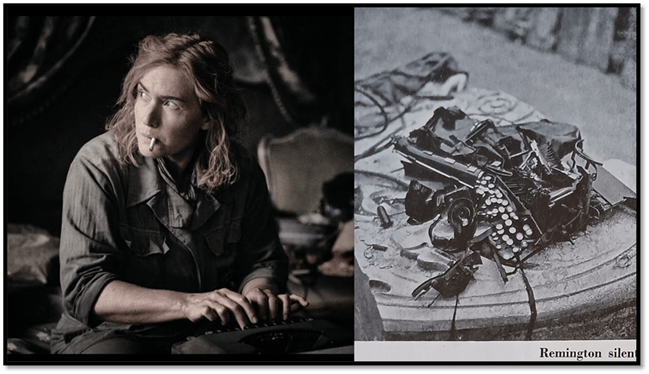

There is an issue in pointing to ‘wordless answers’ given by women, as too near the epicene stereotype of women. However, one review of the exhibition makes it clear that words were as much a medium of Miller’s art as pictures and images. Annabel Downes describes how this relates to her life, just as a wonderful essay by Floe shows how Miller uses mismatches between the messaging of text and image to create further representational strategies, as in Picasso as well as the more stolid surrealists. Downes believes this exhibition opens this up by featuring her manuscript writing (saying of her ‘first person dispatches’ – often used by Vogue editors from letter without her permission but eventually worked into her method – that many are ‘laid out in glass vitrines throughout the exhibition’. I desperately want to see how this is done and to what effects. Downes says brilliantly:

And then there’s Miller’s writing, a side to the job she supposedly loathed. There are tales of Lee hunched over her Hermès Baby portable typewriter, wailing in despair, to be found the next morning asleep on the kitchen floor surrounded by empty bottles of cognac and a sea of balled-up copy. “I lose my friends and my complexion in my devotion to the rites of flagellating a typewriter,” she confessed to Audrey Withers, her editor at British Vogue, who, while a safe distance from any front line, found herself in Lee’s firing line on more than a few occasions. And yet, when she did wrestle the words out, they came with the same ferocity and clarity as her photographs.

Typewriters are persons in one famous photograph of least by Lee Miller (from my early blog):

I do not think we can afford not to try and understand Lee Miller, especially since the Far-right is having incredible successes within democracies that ought to loathe the far right but is not doing so. Miller was a self-identified leftist to the end, though a melancholic one finally. She supported the concept of ‘degenerate art’ not because the Nazis used to dumb down art but because degeneration is a condition of the modern beautiful.

There is so much clearly on offer that will lift me in this exhibition, I do not expect to singing Peggy Lee on exit but rather being raised in mood, hopefully to see Miller anew and as a first-rate artist who transcend theory but who did so not by being a talented pragmatist but an intellectual leader, who nevertheless allowed men to think they were that not her – whether he was her husband, or Picasso, or Man Ray. Now I cannot pin down what happens in the fashion shots but it has something to do with strange exchanges between figure and background, that need more thought – and perhaps will get it when I visit later this month (but perhaps not for her images do not need male words).

So here’s for no disappointment on October 21st.

Is that all there is?

Is that all there is?

If that's all there is my friends, then let's keep dancing

Let's break out the booze and have a ball

If that's all there is

I hope there is more that at the most I think there might be. There is so much clearly on offer that will lift me in this exhibition, I do not expect to singing Peggy Lee on exit but rather being raised in mood, hopefully to see Miller anew and as a first-rate artist who transcend theory but who did so not by being a talented pragmatist but an intellectual leader, who nevertheless allowed men to think they were that not her – whether he was her husband, or Picasso, or Man Ray.

At this time, I cannot pin down what happens in the fashion shots but it has something to do with strange exchanges between figure and background, that need more thought – and perhaps will get it when I visit later this month (but perhaps not for her images do not need male words)

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Sarah Kent (2025) ‘Lee Miller, Tate Britain review – an extraordinary career that remains an enigma’ in The Arts Desk (online} [Saturday, 04 October 2025] Available at: https://www.theartsdesk.com/visual-arts/lee-miller-tate-britain-review-extraordinary-career-remains-enigma

[2] India Block (2025) ‘Lee Miller at Tate Britain review: These images will be seared onto your retina’ in The Standard {online] Available At: https://www.standard.co.uk/culture/exhibitions/lee-miller-tate-britain-review-vogue-fashion-war-nazi-b1250402.html

[3] The ‘Grim Glory’ section of the catalogue has a great introduction by Saskia Flower, which really contextualises the book for me, including detailing which works in it are definitely by Miller and naming the collaborators unnamed in the original: see Hilary Floe with Saskia Flowe (Ed.) [2025: 144 – 161} Lee Miller London, Tate Publishing.

[4] Annabel Downes (2025) ‘The Urgent, Adventurous Photography of Lee Miller’ in Another Magazine (online) [October 03, 2025] available at: https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/16671/lee-miller-tate-britain-exhibition-review-war-photos-vogue-man-ray-surrealism. My emphases.

[5] Damarice Amao (2025: 19) ‘Another Island on the Map: Lee Miller and Egypt, 1934-9’ in Hilary Floe with Saskia Flowe (Ed.) [2025} Lee Miller London, Tate Publishing, 18 – 25.

[6] Hilary Floe (2025: 41) ‘All Just Like Real People: Lee Miller’s War Between text and Image’ in Hilary Floe with Saskia Flowe (Ed.) [2025} Lee Miller London, Tate Publishing, 30 – 41.

[7] Sarak Kent, op.cit.

[8] Annabel Downes op.cit.

[9] India Block, op.cit.

[10] India Block, op.cit.

[11] Deborah Levy (2025: 26) ‘She Is There’ in Hilary Floe with Saskia Flowe (Ed.) [2025} Lee Miller London, Tate Publishing, 26 – 29.

One thought on “Maybe we all put off exposure to the moment of disappointment. Is it because we doubt the reality of our espoused passions? This blog tests that view by exposing my anticipations of the Lee Miller retrospective to be seen on October 21st 2025 at Tate Britain.”