‘Let you in? What like “in” in? …// “With” us? that’s not possible / But, beside us, that’s “doable” / ..’ A place ‘in the mountains’ or, as it truly is, ‘in the margins’. [1] The drama of being put ‘out of place’. This is a blog anticipating seeing Bacchae by Nima Teleghani, ‘after Euripides’.

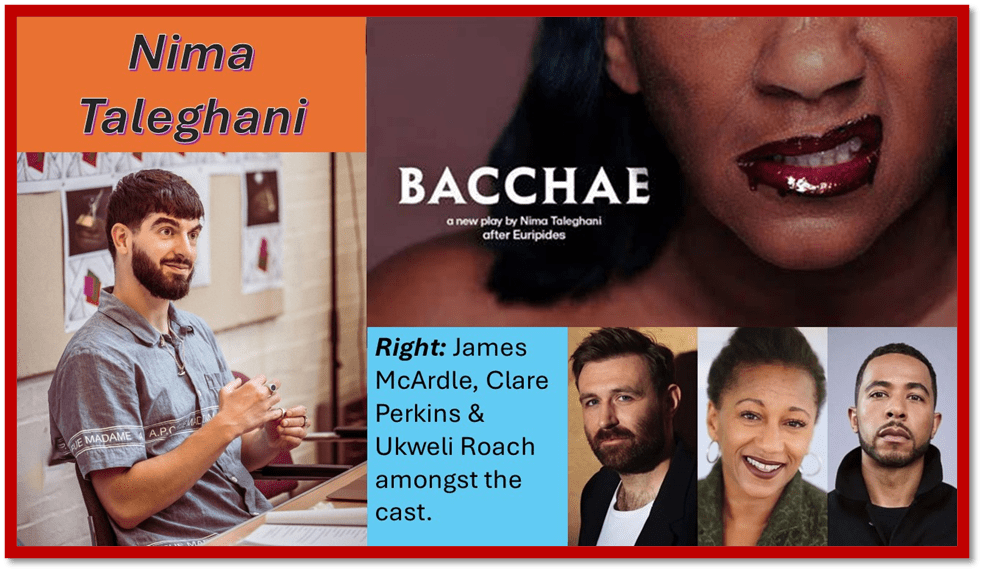

This is another blog on a tangent, that follows on serially from my first preview of my birthday trip to London and to the events my husband, Geoff and I will see on this, his birthday present to me. The first was on the visit to the Theatre Picasso exhibition at Tate Modern on the afternoon of the 21st October (see it at this link)/ This blog is on the event we see on the afternoon of 22nd October, a new play Bacchae, a much free than usual version of The Bacchae by the 5th – 4th century BCE dramatist Euripides (for the original plot use the link).

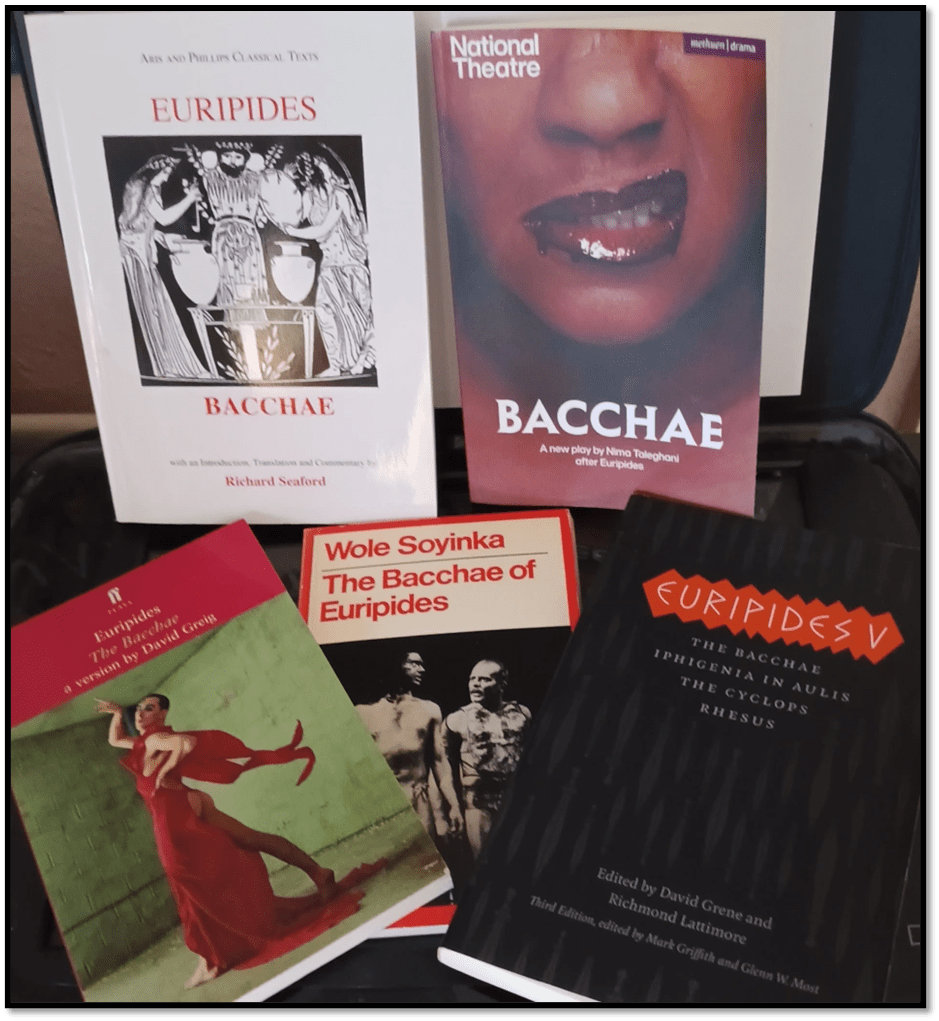

But I would also argue that the blog I want to write is also just on point for this prompt question. All I have read to prepare me to see this play, including Taleghani’ s bold and beautiful text, locates this play in what it is, or feels to be, the phenomenon of being ‘out of place’ (the texts in the photograph below of my own Bacchae library).

According to Richard Seaford’s authoritative account in his introduction to the Aries and Philips edition of the parallel Greek-English text of Euripides’ Bacchae, E. R. Dodds was the first to claim that the original play was prompted by the establishment in the polis or city-state of Attica at the time Euripides was writing, of a cult of Dionysos. Dionysiac ritual was the manifestation of a religion established in the known Global East (on the Tyrian and/ or Egyptian coast according to some and therefore carrying with it rituals that had been ‘added’ to it from ‘foreign’ religions) amongst whom it was established but previously unknown or neglected by mainland Greek city states.

Whether this is so or not, not only Dodds has argued that the play is a response to a sense of an ‘aetiological crisis’, an unfulfilled need to understand why that rise or revival of a cult foreign to the established values and needs of the home polis might have arisen and arisen at that time. This was especially so since this ‘religion seemed to Athenians to disrupt the binary norms that constructed their sense of normality and familiarity. Norms that defined their everyday reality were set it in opposition to otherness that had become to seem alien or foreign. The binaries that structured this were not only the homely-alien but also ( the list is not exhaustive) binaries such as human-animal, order-disorder, reality-fantasy, self-other and significantly male-female). All of these disruptions were associated with the annual festivals of Dionysos, where there was a ritual entry-song into the city known as Διόνυσον κατάγουσαι (‘bringing Dionysos in’):

The actual festival re-enactment of Dionysos’ arrival from abroad may not derive so much from an original actual introduction of the god as from the need of the community to renew and unite itself through the imagined entry of a powerful outsider. This unity may moreover require the symbolic incorporation of marginal elements. I.M. Lewis has shown that in various traditional societies those who are politically impotent, and especially the women, tend to adopt, as a form of protest, cult in which they are possessed by amoral spirits from hostile neighbouring communities. ‘peripheral possession’ that may in time become centrally institutionalised. The polis’ acceptance of the supposed ‘outsider’ god Dionysos, together with the barbarian ritual practices that may have accrued to him, may also signify (or have once signified) its integration of women.[2]

Euripides thus created a drama that recreated and played with the threats that Dionysus disruption of binaries incolved by returning to the myths of its original aetiology, ones that proved that the origins of this foreign religion were in fact Greek, if not Attic, and a bit suspect in that latter fact with Mycenaen settings too because set in Thebes, the very symbol of autocratic rule suring the years of Athenian democracyor partial democracy.

Euripides play is set just after the death of Semele, one of the daughters of Kadmos, following her over-hot rape by Zeus, as a fire that burned her to death during her insemination. The fostering of the hybrid Dionysus, born from that rape, in Zeus’ thigh before he was allowed his divine independence created his claim to be born directly born from the body of a woman and a male God in that order, indeed the Father of Gods. Nevertheless, hated by Hera, Zeus’s godly spouse, Dionysos was not allowed to stay in Greece for his own and his Greek’s dynastic family’s safety from that jealous uxorious wrath, and wandered the coast of Asia, including the grounds of modern Palestine.

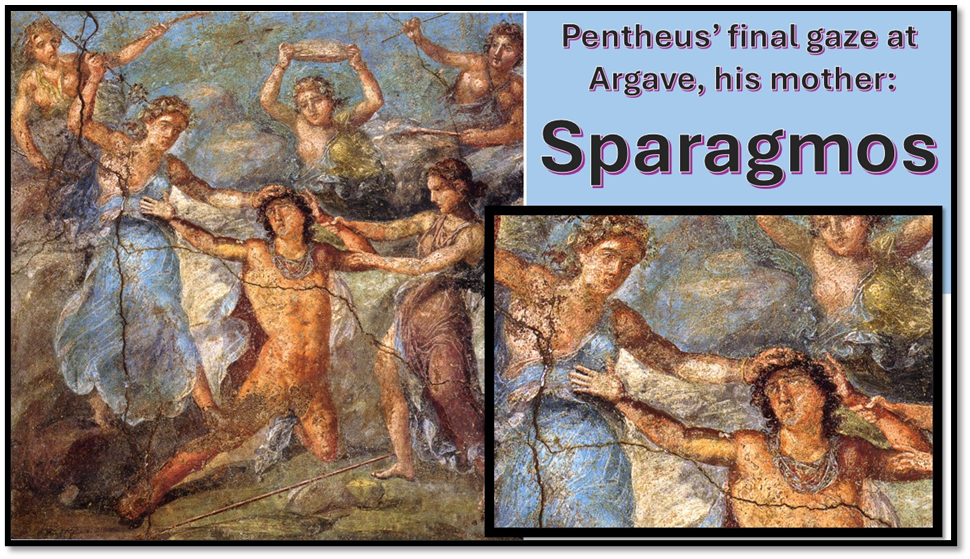

For Euripides, the supposed foreign threat that fed Attic culture wars (a view recently supported by Harry Tanner in his wonderful new book (2025) on The Queer Thing About Sin) was proven as a revival of something missing in the new principles now running the notions of what constituted both the ideal citizen, hoi polloi, and of the ideal polis in which the citizen and hoi polloi is situated. [3] According to Seaford, it is possible that it was necessary to insist that Dionysus was always Greek in order to address the crisis in the Athenian state the Dionysiac female cults addressed: the failure of the state to make space for women and the female power that had been put ‘out of place’ in the ancient Kadmeian state of Thebes, and perhaps Euripides thought, in the polis of 4th century Athens. The tearing apart of the body of Pentheus (only reported in the Euripides text but actually theatrically enacted it seems in Teleghani’s text, For Euripides may have meant the symbolic sparagmos of the patriarchal idea of control of the irrational and subjective (associated in the old order with the queer, the animal and the female) Just as the tyrannous dynasty of Kadmos had to be symbolically exiled from Thebes for Dionysos to establish his cult.

I labour this point by a very traditional scholar of Ancient Greek culture, as Seaford is, because today the reviews of The National Theatre production have begun to appear and have, as far as I have got in reviewing them to be universally damning of the version’s temerity into turning high drama into satiric politics as they see it. But clearly Euripides was capable of laughing at the high minded male self-control of Pentheus as a man who outwardly claims his masculine purity, and that of the steely armour that represents it, but still longs , but The Times leads the assault with this title – since they use paywalls I have not gone further into the likely sludge of this crudely nasty beginning: ‘Bacchae review: a tragedy of blunders as leaden update falls flat; The actor Nima Taleghani’s update of Euripides’ tragedy at the National’s Olivier theatre is a crude and timid start for Indhu Rubasingham’s reign‘. Not far behind in nastiness, the online Broadway World reviewer, I keep the crude misspelling of ‘crudely’ intact, says:

Bacchae arrives trumpeting fist clenched rebellion, only to implode into hashtag politics. In remoulding crudly Euripides’ tragedy into tawdry cabaret, the National Theatre has committed the deadliest artistic sin of all: cringe.[4]

The sin of this play is possibly, for these critics its allowance, as the first debut play, by a first generation Iranian British writer, staged on The Olivier stage at The National Theatre and first directed and commissioned by new directorial head, Indhu Rubasingham. As you spell that out you can’t help feeling that these critics are responding as much to what they may feel is alien takeover of the national stage of England. The play, as all these critics say actually bruits this ‘presumption’. The Chorus leader of the Bacchae, Vida (foster mother of Dionysos for this version of the story) asking: ‘Why … is the Magnanimous Badgal Vida ? Here in Thebes directly addressing us in our Royal National Theatre?‘ (p. 6). And why the rap terms ‘Badgal’ they might ask. Vida provides again, as ‘bad gals’ do, at the end saying: ‘After the God of Drama steps in ur Royal National / Theatre shit’ll never be the same’ (p.106). After all her Baccic troop are already defined by her as not Euripidean classical: ‘we dem dis-ain’t-what-u-quite-expected-from-the-retelling-of-a-classical-play-bitches‘. Read those words as provocations to critics whose expectations are what they are entrained to be and those reviews begin to seem challenged to say: ‘We see what you are saying but you just ain’t good enough to get away with your claims – on this mighty ‘Royal National’ stage!’.

My favourite line (so much I yearn to hear it live – how will it be pronounced – is the one that performs the drama of high and low art by summing up the whole play, when it is not Browning’s Pied Piper, as ‘Tonight the Artful Dodgers have taken over the Oliver‘ (page 105). It is just street theatre talk but, as with classic art and with the same pretention when described ‘it works on so many levels’. First in Dickens, the lumpenproletariat boys of London take over a boy who will later be proven to be of genteel birth. Second, the musical Oliver is often taken over by one cheeky cap, ‘considering himself alright’, and third, an artist who has dodged the establishment theatre (Aleghani) has taken over ‘the Oliver’ (get it – the Olivier’) named after the most mannered and tailored closet actor of them all – ‘dear old Larry’, Laurence Olivier.

Even the most nicely worded negation of the value of this play-project by Heather Neill has nevertheless a similar tone of disappointment that is stressed in order to show that ‘it serves the director, writer and actors right’ to thus provoke us with their hubris – particularly given their subaltern cheek against us, ‘ain’t we the entitled largely white establishment’ justifying itself, we critics! Whilst, unlike the others Neill finds in the production enough to justify that, despite ‘the drawbacks there is enough here that augurs well for the next few years’, on the Olivier stage, she means. Hence she is clear that: ‘In the final scene Dionysos is delighted to be recognised as the God of Theatre. This is the real crux of the production’, and that the whole adds ‘up to a celebration of theatre’. But the reference to drawbacks still concerns me. Here is Neill’s explanation of why she sees drawbacks:

Whereas Euripides has Dionysos seeking revenge for the lack of respect for his dead mother and the refusal of the Thebans to worship him, here he is looking for a home. By the end, there is an explicit plea for the acceptance of migrants. There is nothing wrong, of course, with drawing modern parallels out of the classics, but this does put more emphasis on the human side of Dionysos’s nature than fits with his immortality and ability to pull off magical tricks. Ukweli Roach makes him an engaging figure, more good friend than advocate of excess. The blind prophet Tireseus (Simon Startin, a sardonic presence) tells the truth unheard. (my bolding) [5]

The other critics, as well as Neill, and more heinously, stake out their right to admire and venerate the classical tradition as evidence of their learning and critical insight, but the case against such pretence in the interests of ‘traditional’ theatre in which politics and modernity is all ‘turned off’ in the interests of classical authenticity is that too often its spokespeople just get it all wrong in the first place. The issue of migrancy is at the core of the myth of Dionysus, the rituals, their derivable meanings and indeed Euripides’ dramatic practice using the genres of a Greek theatrical toolbox. Why are these people so offended by the notion that some of us, and I think Euripides too in 4th century BCE Athens thought there was a need for an ‘explicit plea for the acceptance of migrants‘ in a Athenian polis already in explicit decline, and rather tired. At last we cannot rule that out for if we read Seaford’s scholarly piece as we should it is clear that the mythical story of Dionysos, and Euripides’ rendering of it, was always a nostos, or ‘homecoming story’ (as much as Aeschylus’ Agamemnon is but here where a god not a king comes home to find it queerly changed) and that this would have not needed explaining to Euripides’ audience.

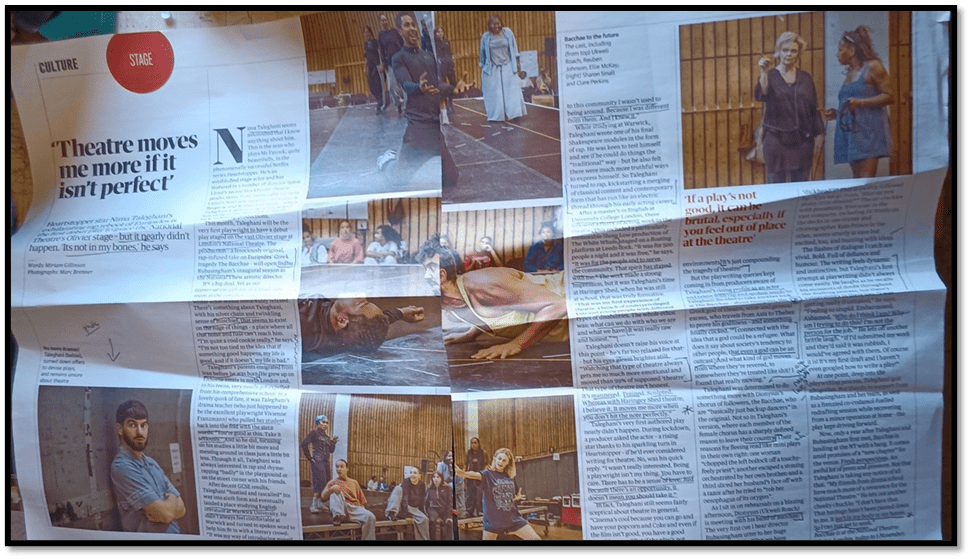

And I find it even more crude for people to abstract from classic Greek drama the ‘human’, as if Plato did not show tragedians like Agathon sitting at the same symposia discussing the dilemmas of human life with Aristophanes, who no accuses of being high-minded and above crude humour and human content with a queer edge, sometimes, in his Frogs, for instance, at the expense of Euripides claimed liking of dressing up as a woman (Aristophanes was not liberal in his politics nor his view of social identity but this supports the hypothesis that discussion was afoot in Athens nevertheless in their common time in history). And, in point of fact, Taleghani seems to have expected and perhaps feared the effect of a backlash from the the theatrical establishment and its poodle critics. The article on his involvement in the play, before it commenced, in The Guardian (see the photograph below) seems to anticipate that critics would find it far from ‘perfect’ (and he is correct).

Moreover, perhaps he is correct too to diagnose that theatre that is aimed at living rather than notional communities rather than a ‘fit audience though few’ is more honest. His ideal theatre Taleghani says is ‘for the people and to serve the community’ whilst the theatre that is dominant in the West and South, and mainly inaccessible for ‘the many’ ‘is,t honest. It’s mannered. Trained. Sculpted’. [6] How many other words might he use for over-regulated, just as poor Pentheus is over-regulated in his play (and Euripides’). For instance take this snappy dialogue in Greek, which follows Pentheus’ supposedly shocked but really interested anticipation of seeing lesbian sex in the bushes in his trip up the mountain dressed as a woman, imagining himself hidden as ‘I suppose them to be in the thickets like birds, held in the most pleasant nets of love-making‘.

Dionysos: ….

κε̂ιθεν δ’ ̀απάζει σ’ ̌αλλος… (another will bring back from there)

Pentheus: ́η τεκο̂υσά ε. (Yes, my mother)

Dionysos: ̀επίσημον̆ οντα π̂ασιν (Conspicuous to everybody)

Pentheus: ̀ ̀επ̀ι τόδ’ ̀́ερχομαι (That is why I go)

Dionysos: φερόμενος ˝ηξεις ... (You will come carried ...)

Pentheus: αβρότμτ’ ̀εμ̀ηνλέγεις. (What you describe is luxury to me)

Dionysos: εν χερσ̀ι μητρός. (In your mother's arms)

Pentheus: κὰι τρυφ̂αν μ’ ̀αναγκάσεις. (You will compel me to be pampered even)

Dionysos: τρυφ̂άς γε τοιάσδ’ (Pampering in my fashion)

Soft and hard men (Dionysos playing soft: men in uniform appear hard but are they?

However much you address the Greek verse with high-faluting words – it is constructed from hemi-stychomythia, for instance – a technique where standard metrical verse lines are split in half and attributed to actors speaking together alternately, the whole plays with clever jokey ambiguities about what it means to be carried (for in fact Dionysos knows only Pentheus’ head will be carried back by his mother, on the tip of her spear) that cleverly show that the supposedly hard man, Pentheus, is in fact soft and needy – wishing ever for the womb of his mother and to be pampered like a very young child who has not yet grasped the thorn of the consequences of adult masculinity as he sees it. The same joke is played with his longing to regress by Euripides’ Dionysos where drag is not a statement but a delightful experience.

This is not a million miles away from scenes in Taleghani’s version which I long to see in the flesh, to see how they are carried off, bu twho conveys messages rather differently, though still in stychomythia (for after all Euripides was a canny innovator of how to do dialogue).Taleghani’s scene starts with rap to show to Pentheus the foolishness of this man fearing to be ‘…soft‘.

Soft? Scared to feel soft?

U think it's less scary to be hard, cover yourself with armour n steel?

I'd find it much scarier not to feel.

An who says who can wear what? So silly, wear anything, be flippin' free!

'Gender', 'identity', 'sexuality' - what frivolous ridiculous, mortal concoctions

'Ooh I can't wear that, Ooh I can't sex them, that would make me x, y or zee' [page 75]

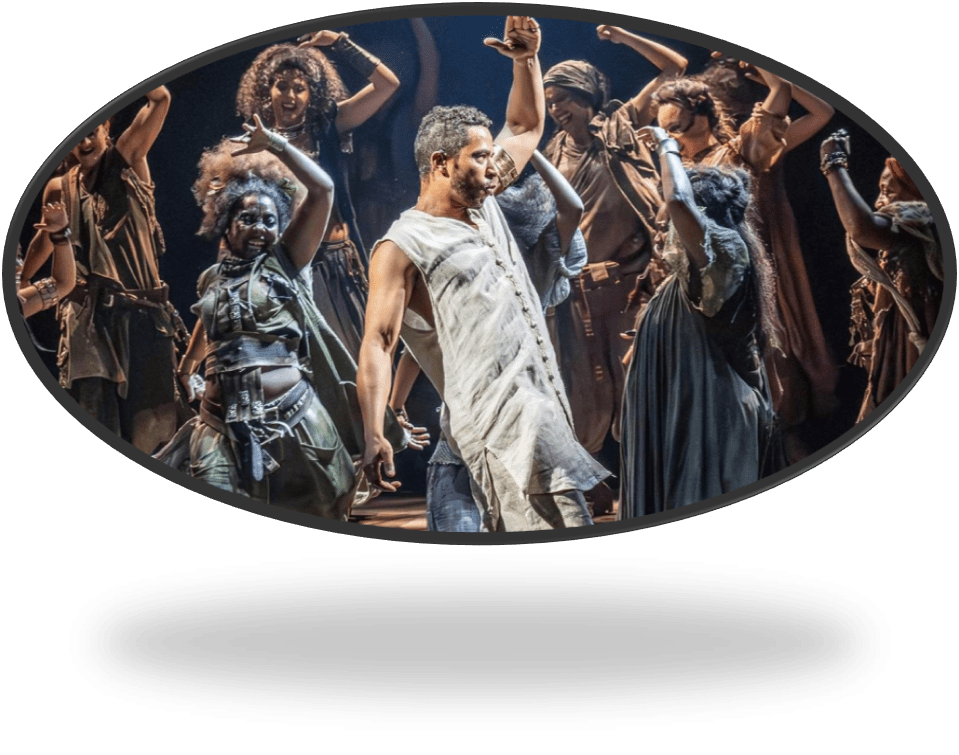

If I dare I think the critics who see this as full of ‘modern’ politics – here sexual politics, fail to see how beautifully this fits the bill than productions that focus sexual politics (which, as we have seen, Euripides did too) that were feted because the did not ‘play the race card’ (as again Euripides DID!). Alan Cumming is one of my favourite actors but his highly praised Dionysos from David Grieg;s version of the play turned the exploration of sex/gender/sexuality (embracing these margins) it seemed to the critics (I am still fuming that I failed to get a ticket to see it) into high camp and bum shots. In the dress reheasal shots from Taleghani’s version Ukweli Roach appears to play Dionysos not as ‘mannered’ in the high acting tradition but as fluid – shifting not only by what he wears but his exploitation of scenes and persons. In the collage below he uses his female followers as an armchair – does he abuse them (the scales of evaluation I think will shift when I get to see the play in the flesh.:

the unattributed What’s On Stage review of Grieg’s Bacchae, shows what passes as what Taleghani calls ‘theatrics’ in his text and sort of shows a political distaste for in The Guardian piece cited above.

“So, Thebes…I’m back!” declares Alan Cumming as the disguised god Dionysus, descending from the flies upside down, bare-bottomed and manacled in a gold lamé unisex suit.

It is the first of several stunning coups in John Tiffany’s starkly vivid production of The Bacchae by Euripides for the National Theatre of Scotland, premiered at this year’s Edinburgh International Festival and now running in Hammersmith after a brief visit to Glasgow.

The god of wine and ecstasy, son of Zeus by Semele, daughter of Cadmus, is outraged at being an outcast and has formed a tribe of vengeful, orgiastic women, the Bacchae, who are running wild through the mountains; they materialise as a bunch of hot-gospelling red hot mommas in various shades and styles of scarlet, all black and singing the blues. [8]

It makes me ‘cringe’ more than I think I am capable how easily theatrical acting is seen here at its best in its camp followers – and I say that with no disrespect for Cummings. I love him. But this is a travesty of culture war politics and is not therefore recognised as such, though I am sure Cumming will recognise it as such. He has some powerful grasp of performance values. When I look at the theatre still for Ukweli Roach below, playing Dionysos dressed up as a token male Bacchae, I sens that the transitional male-to-female identity markers are subtle and emerge in the gestural action of hands and face, rather than just being cheeky, as with the four cheeks of Alan Cumming so apparent in the dressing of his role – and why not (he has a shapely androgynous bum). Covering his hard breastplate – in the photograph above – is a leopard effect top (not showy but by contemporary standards ‘feminine’ in design), he seems to have natural breasts – though in reality hard is masquerading as soft. This is good theatre and not mannered or tailored, and it is good politics – what in the 70s in Gay Left collective followers we called ‘radical drag’.

However, it is well beyond time that this blog got serious about why it is right to take the theme of migrants and race on board and defend the right of theatre to take on highly current debates where so much is based on a homenpolitics of deceit about, and pretence of representing authentic community. Let us summarise first what I have said already about the representation of the political in Bacchic terms.

Euripides’ Bacchae is a play that welcomes bloody revolt against the old powerful families that hold power as national and familial patriarchs-in-the-making and law makers – attacking them bodily and even devouring them. The play cools down its viscerally violent effects (some classicists believe) by the establishment of a new cult religion to contain the energies released for that former purpose. In parallel, Wole Soyinka wrote a version in which the political freedom of slaves versed in African folk culture is achieved despite the heavy costs of getting to that historical and philosophical achievement. Taleghani looks at politics in terms of real communities, not represented as choruses saying the same thing but communities riven by internal conflict about what they are and how they should perform.

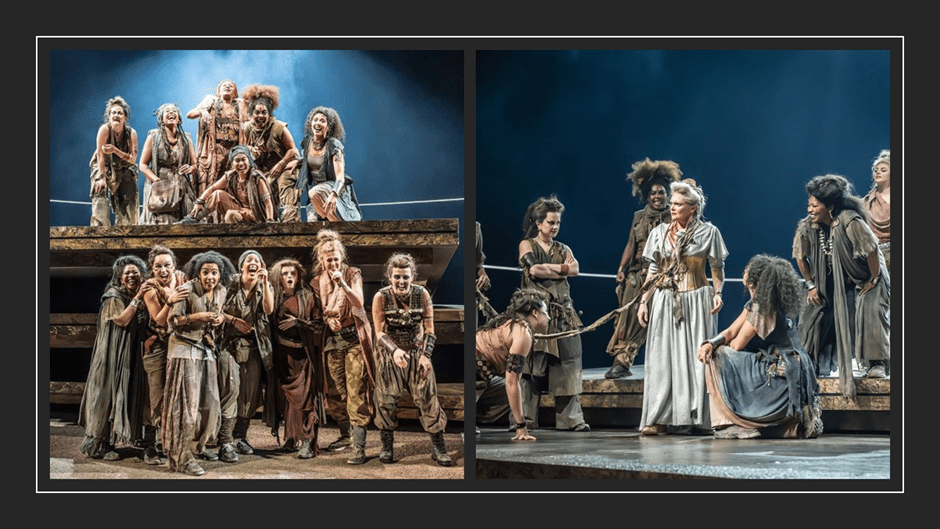

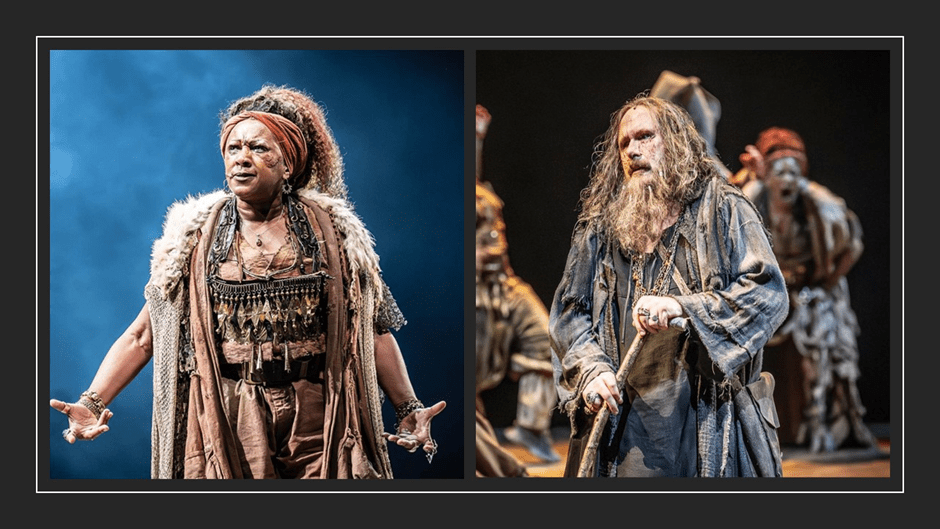

Of course, the characteristics of the Greek chorus, or cotps de ballet in classical dance, remain I suppose or the photograph below seems to show that.

Yet the theatre stills also warn us that stage design, lighting, and setting does not emphasis symmetry and homogeneity in groups but conflict, even in how to deal with one’s putative enemies, like Queen Argave.

The play works chiefly with the concept of inclusion, at its easiest in the piece of text I used in my title from the discussion between Dionysos, acting the role of the ‘camp’ follower of the God, and Penthesus, where Penthesus sets out his plan for the migrant Bacchae, to settle them in a remote and inhospitable part of the city-state: ‘the mountains’:

DIONYSOS: Mountains? In the margins?

What is your obsession with marginalisation?

I am never going back to being a Marinalised Asian.

Can't you find it in your heart to let us in?

PENTHEUS: Let you in? What like "in" in?

DIONYSOS: Yes with you!

PENTHEUS: With us? that's not possible

But, beside us, that's doable

I don't get the problem cuz it's a terrific offer, no?

That';s my Olive Branch

DIONYSOS: Foreigners aren't tryna rob u blind & cause violence - that ain't why we seek asylum [page 93]

Of course it is over-simplified and of course the representation of the Bacchae variously as foreigners (page 30), refugees (page 35), and ‘asylum seekers’ (page 44) twist what the Greek chorus in Euripides represents but not in a way that cannot be seen as latent in Euripides, if we but knew enough about the politics of the declining city-state, aware of the rise on the horizon of Philip of Macedon. Likewise the crossover between issues of classes considered liminal – insufficiently defined because they cross borders – even cross-dressers, trans and non-binary people (and gay men, lesbian women and queers) is meant to be covered by definitions that ‘wander’ as do nomadic peoples (often from no choice of their own but though some might make that choice in order to live more fully) and of course women – by birth and/or choice. Both Vida and Tiresias cross boundaries and both are a kind of blinded seer. Again I can only wait and see how this might be suggested.

The exploration of masculinity in relation to armour and war must ring bells given parallels continually drawn between Israel claiming the whole of the homeland of people they other and are warring down to death, just as it must in the rhetoric of Donald Trump. enforcing every nation to ‘man up’ with ‘arms’. The obsession with strong leadership is surely another issue Euripides anticipated and this version of the play explores in Pentheus childlike regressions. even when he tries on what he supposes are female feelings: ‘if I was a woman I think i’d feel afraid’ at a level deeper than his boyish characterisations of a ‘damsel in distress’ and the moment being Dionysos (in bold below)and Pentheus which is difficult to see equivalent for in other versions, including Euripides, except by extrapolation:

‘I mean its even scary sometimes just being a man’; ‘Yeah fuckinell‘; ‘Fuckinell … yeah / Everyone expects you can … expects you to …'(page 87).

That line from Dionysos may be played as part of the camp of the role the god is playing but I think not. The key part of the key word is ‘in’. What are men included in is the same question as what is inside them if we dare look? It is only when shaken out of role that it appears possible to even think about that, and I find that profound sexual politics and profounder in terns of international transitional politics and international and inter-race relations.

There is the question in this text (how will it play out on stage in the flesh) that ‘Freedom’s on the other side of ONe Last Riot’ but that is the very individuated Kera, in the cast list described as’ next gen, ruthless bacchae’, a step down from Vida as ‘the ‘most violent’ bacchae’ but this differentiation between the divided women shifts – for some or, at least, there is the possibility of ‘internal rebellion’ (page 85), just as there has been in what is branded feminism, as if it were one thing. Why can’t we write verse drama about this, and recognise both that Euripides did the same, and did it as as way of reflecting ideological conflict and its non-binary nuances in his own time. Now Euripides MAY have thought the Dionysian baccanalia were a kind of polical resolution: either in shifting our subjective boundaries to include more possible alternatives in life, but the divided world of this play doesn’t, at least when read – but I will report back.

Does Nima Taleghani’s new version Bacchae stops short of consolation: religious, social, or political? On the understanding that he had been rejected by his family, city state and family and denied anything that might represent a home for him and made instead to seek asylum, as a ‘marginalised Asian’, Dionysus takes terrible vengeance on the state, family and carers. He learns that his full belief in his callous rejection only after he has destroyed the life of the woman he believed to have acted as the source of rejection. itwasn’t exactly ‘rejection’, it was motivated by ‘protection’. It is too late to reverse what has happened (and anyway there was some justice in his actions too), and he turns in childlike despair, as boys oft do, to the woman who brought him up, Vida, asking ‘What do I do?’. She says: ‘Live. Live with what u done son’.

Is this all that the God of Theatre can offer us in its national UK powerhouse? And how will it feel to see , hear and feel all this performed in that place? The point is, we all get things wrong all the time, but if we let that stop principled action, then Keir Starmer comes to mind – a man confused unlike a man merely opportunist as in Nigel Farage (like Boris Johnson). We have to act in ways that sometimes have consequences we would prefer not to be there. But the price of not doing is UNJUSTICE. Of course there must be plays about that. More please, Nima Taleghani.

Just because men keep pricking out the point, doesn’t mean they have one!

Bye for now

With love, Steven xxxx

| Tuesday 21st October | Wednesday 22nd October |

| 10.30 a.m. Lee Miller’s Surrealist Photography at Tate Britain, Millbank: Followed by river boat to | 10.30 a.m. Gilbert and George retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank |

| 2.00 p.m. Theatre Picasso at Tate Modern See this blog 7.30 p.m Punch Play by James Graham, Apollo Theatre | 2.30 p.m. The Bacchae A new play by Nima Taleghani after Euripides, The National Theatre. THIS BLOG PREPARES |

[1] Nima Taleghani (2025: 93) Bacchae London, Methuen Drama.

[2] Richard Seaford (1996: 44ff.] ‘Introduction’ in Richard Seaford [Ed] Bacchae: Greek text and facing literal English translation, Oxford, Aries & Phillips. 25 -54.

[3] Harry Tanner (2025: 48-50) The Queer Thing About Sin London, Bloomsbury Continuum. Adduitional Note. The Greek appellation for the people (hoi polloi, which is literally ‘the Many’ and the source of that phrase to indicate the people set against oligarchy – ‘the few’ – in Shelley’s Masque of Anarchy. Hence since ‘hoi’ already means ‘thet’ I have omitted using the common noun-phrase ‘the hoi polloi‘.

[4] Alexander Cohen (2025) ‘Review: BACCHAE, National Theatre’ in Broadway World (online) (Sep. 25, 2025) Available at: https://www.broadwayworld.com/westend/article/Review-BACCHAE-National-Theatre-20250925

[5] Heather Neill (2025)’Review: Cheeky, Uneven Version of Euripides’ tragedy’ in The Arts Desk (online) on Thu, 25/09/2025 – 00:18 Available at: https://theartsdesk.com/theatre/bacchae-national-theatre-review-cheeky-uneven-version-euripides-tragedy

[6] cited in Miriam Gillinson (2025: 43) ‘Theatre moves me more if it isn’t perfect’ in The Guardian Weekend Supplement (Sat. 13th Sept 2025): 42f. (pictured above in the copy I read it in)

[7] Euripides (Richard Seaford [Ed]) (1996: 118, lines 966ff.) Bacchae: Greek text and facing literal English translation, Oxford, Aries & Phillips. 25 -54.

[8] What’s On Stage Editorial Staff (2007) ‘Review: David Grieg’s version of The Bacchae for the National Theatre of Scotland’, London’s West End in What’s On Stage online (10 September 2007) Available at: https://www.whatsonstage.com/news/the-bacchae_20557/

Heather Neill on Thu, 25/09/2025 – 00:18

“

https://theartsdesk.com/theatre/bacchae-national-theatre-review-cheeky-uneven-version-euripides-tragedy#

5 thoughts on “‘Let you in? What like “in” in? …// “With” us? that’s not possible / But, beside us, that’s “doable” / ..’ A place ‘in the mountains’ or, as it truly is, ‘in the margins’. The drama of being put ‘out of place’. This is a blog anticipating seeing ‘Bacchae’ by Nima Teleghani, ‘after Euripides’.”