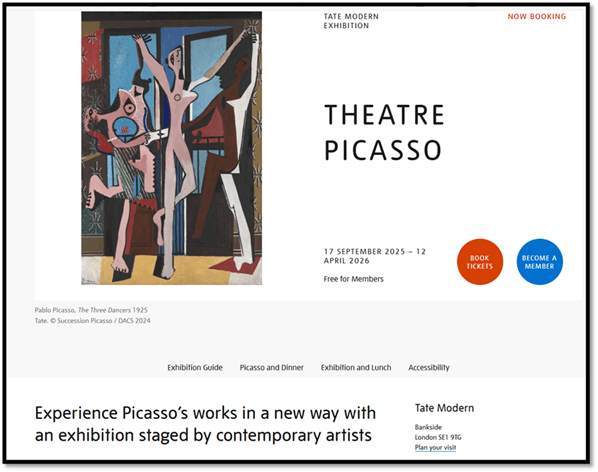

What could I do more of? I could allow art and ways of seeing it to challenge me more: a preview of what I expect from the ‘Theatre Picasso’ exhibition at Tate modern, which I see on October 21st 2025.

There is nearly always a debate these days – though perhaps there always was before – about how and why British institutions and the values they support have declined in significance and gravity of message. This is inevitable as those institutions speak less to the few that once felt entitlement and ownership of those values and literally turned them into material objects, where monetary value equated with values the old guard pretended to be spiritual or otherwise transcendent. Recently that debate has turned its attention to the Tate amongst other institutions (I am waiting next for the outcry about The National Theatre under new and challenging management with its first production, The Bacchae in street rap style, but that is for a blog to come soon). The London Evening Standard always obliges calling the Tate recently an institution that has gone ‘broke on woke’, a judgment followed up by the brutal piece linked here.

However, art no longer serves a few powerful patrons that could command and dictate its content (the Catholic Church either locally or internationally after the Counter-Reformation), with the artist seeking to find some hints of liberation – perhaps even the Bernini – in their individuating manner of execution of an agreed topic. For years that awful discipline called the History of Art replicated all that by demanding we use evidence from the art-maker, patron or contemporary public to reveal the ‘true’ meaning of an art work rather than merely one situated in another space and time – most notably and laughably in the case made for an iconographical reading of Titian’s The Flaying of Marsyas) that turned its back on those unable to cope with its calculated violence, insistent that this was all symbolism and nothing else.

I will follow through on that argument later, but first to reason prompting me to choose this WordPress question to answer. After a year saying I was 72 this year, I calculated again and find that on October 24th I will be 71 not 72. That is worth celebrating and Geoff has bought me a three day arts excursion to London for my birthday from October 20th for arrival to departure on the 23rd, in time for pre-booked tickets for the Durham screening that evening of The National Theatre’s new production of George Bernard Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession. Part of the package in London are four art treats (he insists we limit them to four as follows but they all represent artists I already love, if mixed with other influential shapers – about which more in the individual blogs on my (usually research-of-a-kind-informed) expectations of each (I will link blogs to this table as they get written, but this is the first):

| Tuesday 21st October | Wednesday 22nd October |

| 10.30 a.m. Lee Miller’s Surrealist Photography at Tate Britain, Millbank: Followed by river boat to | 10.30 a.m. Gilbert and George retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank |

| 2.00 p.m. Theatre Picasso at Tate Modern 7.30 p.m Punch Play by James Graham, Apollo Theatre | 2.30 p.m. The Bacchae A new play by Nima Taleghani after Euripides, The National Theatre. |

No doubt the theme of the question here may apply to each of these performances / exhibitions, perhaps with the reception of the safe bets around Imelda Staunton in Shaw’s dated social drama about sex and money. To prepare for Theatre Picasso (as I always prepare) I have read two rather good reviews, one in the i newspaper (by Florence Hallett) from Thursday 18th September and another by Jonathon Jones (in an excellent piece where he tones down his usually bitchy remarks about modern curation of classic art) in The Guardian Weekend Supplement from Saturday 30th August. I also purchased the paperback version (to save money) of the catalogue: Rosalie Doubal & Natalia Sidlina (Ed.) with Wu Tsang & Enrique Fuenteblanca (2025) Theatre Picasso London, Tate Publishing.

Having read all this and examined the representations of the exhibits I remain still with huge gaps in my expectations of what Geoff and I will see on the 21st October, and that is, I think a good thing, even from the helpful descriptions of the curation style in Jones’ article. What is clear that the use of contemporary artists and perspectives from performance and queer theory in the catalogues commissioned essays by on-the-ball writers, the curation the representation of contexts for reinterpretation devised not by scholars, but by contemporary artists of works, already subject to years of art historical over-interpretation and, to put it frankly, myth-making, often of the kind that kills off the socio-political meanings of the art at the expense of the mythologies that still guide art history, even when it is critical of older paradigms of its subject’s ideological content. So I am making no clear predictions here: leaving room for hope-for surprise in the event, though in truth I have never seen in the flesh the painting at the centre of the show, the huge and culturally weighted picture that is The Three Dancers (1925), despite visiting recent Picasso exhibitions. That’s probably unforgivable for it has been hanging in the Tate’s mainstream collection since 1965 and I was a student in London in the 1970s.

But what is clear I think is that the attack on the Tate, from The London Evening Standard downwards to even lower guttering than that in which the latter paper lives, is entirely one in which ‘standards’ are upheld that no-one articulates but which are those of which past sages once held along with privileged status, wealth and power to symbolise the value of their own power over others. They still do that but now use very contradictory populist rhetoric that engages only with the many at the level of stereotypes of a reactionary obfuscating antagonism to any leaning that is counter-intuitive, as all learning worth that name must be. They need a public that reveres not art but the symbols of social power, which art once solely was in their hands and which they want it to remain, so that learning stops before it becomes critical (of the necessity of their power bases). So much is that the case that they mock ‘élites’ who really only want to share learning not hold on to it forever.

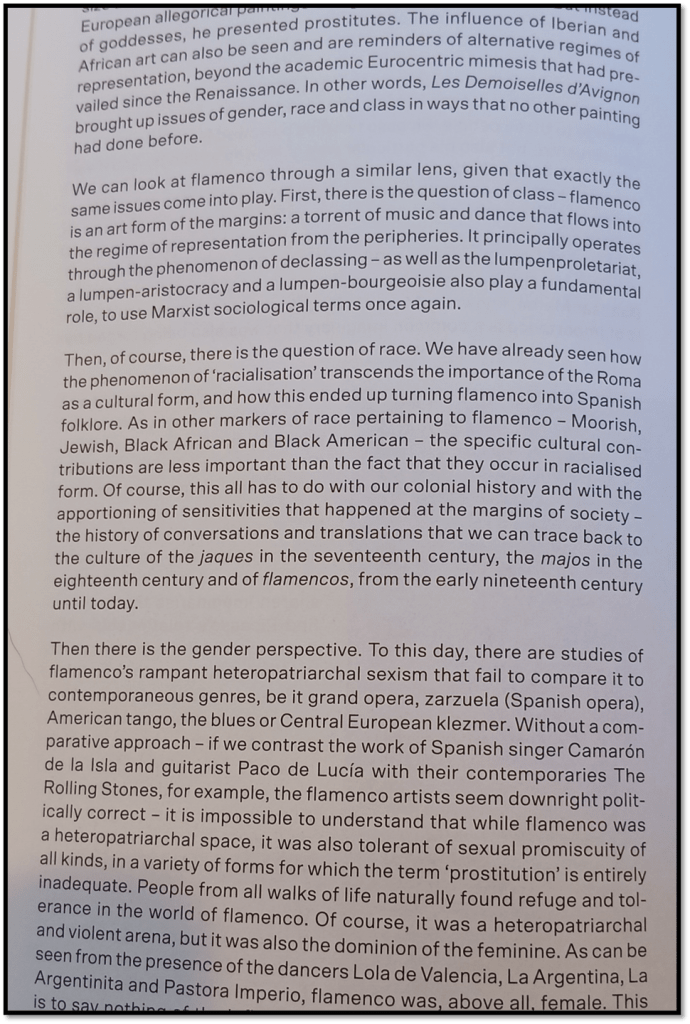

Nevertheless sometimes modern and post-modern art commentary, and sometimes the art, plays into the hands of these critics – given that critical thinking, unlike ‘common-sense’ (usually common-nonsense or disguised folklore) is based in the complexities of the real world not its reductive oversimplifications. From reading the essays in Theatre Picasso, there is definitely a danger of that here, that supporters of cultural change need to take seriously. Let’s take an example from an essay from the catalogue by artist Pedro G. Romero, an essay of clear brilliance but also of an unforgiving density of language and reference, that tries to work with concepts in the analysis of class (especially Marx’s concept of the Lumpen class variants). The Lumpenproletariat, and Lumpen-bourgeoisie(not a concept I have met before) are not defined by the relations as of production in a class-based capitalist economy but do have relation to the class system nevertheless, usually as consumers and/or ways of living off economic production conducted by others. Amongst the Lumpenproletariat the early Marx (in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte) included criminals, beggars, and nomadic travellers – it is a problematic category and always was and was later abandoned by Marx, who himself was most probably classifiable, unlike Engels, as Lumpen-bourgeoisie, as artists who do not make art primarily for sale would be. After his list in the Eighteenth Brumaire he summarises them almost comically: ‘the whole indefinite disintegrated mass, thrown hither and thither, which the French calle la bohème.’[1]

In the few paragraphs below, Romero begins with an explanation of Picasso’s turn to ‘alternative regimes of representation’ from those persisting in past art and its formulations in art history and criticism (‘academic Eurocentric mimesis’). As his chief example, he (and the curators / editors of the exhibition use the Lumpen characteristics of the origin and maintenance of ‘flamenco’ dancing as an example of a performance that had no traditionally validated history but grew from Lumpen and marginalised classes, notably the gitano celebrated by Lorca in poetry and Picasso and others in painting. Romero links this representational shift to what he sees as underlying issues of the representation of race, and concepts of ‘racialisation’ of the ‘primitive’ in Eurocentric thinking) in one paragraph. In the very next paragraph he links those issues to the representation of sex/gender and sexuality – especially to non-conforming women. I say this, possibly with as much density as Romero in order to show the complexities of analytic thought he evokes as well as the range of reference to practices not thought to contain objects worthy of classification as knowledge within the boundaries of academic or any other knowledge that gets that name – things to do with the margins of that we think of which we need a sure and certain knowledge. But have a go with the passage yourselves.[2]

It is not just that this is not easy reading but that it lives and breathes what is becoming to be known as ‘woke’ concerns. What ‘woke’ thought is ought to be more disputed than it is, now right-wing populism has metamorphosed it into a negative phenomenon akin to obsession with was once a positive thing – awareness of introjected concepts that cause the ‘sleeping’ oppressed to accept their oppression as natural and inevitable. To wake and be ‘woke’ is the equivalent of new self-awareness in response, for instance and in origin, to the phenomenon of racism. But it is easily applied to the idea of women who become feminist in their thought and feeling or to queer awakening to a sense of one’s own validity despite oppression telling you the reverse. It is for this kind of thing the Tate is continually being lambasted in our days. But my point is that sometimes we need to remember that complexity of thought needs less dense explication not demonstrations of the breakthrough intelligence, insight and non-canonical knowledge bases (such as the deeper history of past Flamenco dancers) that we might see in Romero’s prose. Yet no-one who is proud to be ‘woke’ can avoid this problem if they turn to explain the hidden complexities of art no longer current – and compounded with oversimplifying myths that pass for knowledge about Picasso.

Of course the Picasso explicated up to now has most often been one divorced from the politics he espoused and saw as central to his creative making of art. To be fairer the academic art historian Patricia Leighten in another essay in the catalogue says that: ‘Picasso’s politics used to be cordoned off from his art. In the last few decades, his work has been reinterpreted in light of his early association with the Barcelona, Madrid, and Paris anarchist movements and his later membership in the French Communist Party (PCF)’.[3] Of course Leighten was herself one of those voices of ‘the last few decades’ and there must be a sense in which this essay is also saying: ‘and you still haven’t understood my contribution or have marginalised it’. Yet none of this ‘woke’ stuff may be central to how I see this exhibition.

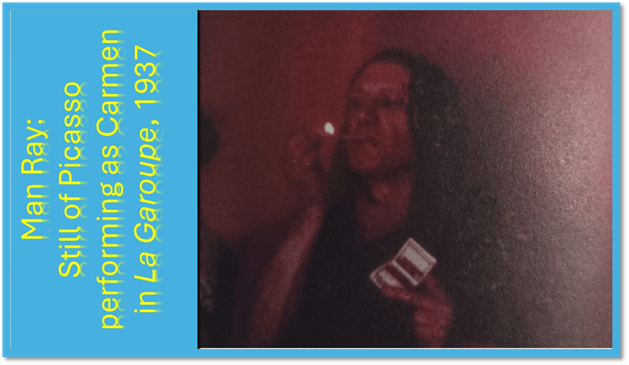

The artists most important to Theatre Picasso’s curation as an exhibition, Wu Tsang and Enrique Fuenteblanca, say that the novelty of it is the inclusion of a ‘performance programme’ in which, artists have used performance art to explore ideas (’whether directly related to Picasso’s work or not’) that intersect with Picasso’s themes in the art chosen for the exhibition. In a ‘conversation’ in the catalogue with one such artist, Yinki Esi Graves, with whom they have worked before in relation to the performative aspects of Bizet’s Carmen gets near to why performance will be made a central practice in understanding the Picasso works in the exhibition. The link to Picasso all three contemporary artists use appears in the exhibition it seems in what Jonathan Jones calls the ‘most gossipy exhibit’ in Theatre Picasso: ‘a clip from a movie shot by Man Ray,’ wherein ‘the stocky painter’ (he means Picasso – though Jones himself is on the ‘stocky’ side) ‘drags up as the opera heroine Carmen. “It’s a bit of a gem to me to see him with the mantilla and the cigar,” sats Tsang’.[4]

The picture and caption from Rosalie Doubal & Natalia Sidlina (2025: 16) ‘Introduction’ in Rosalie Doubal & Natalia Sidlina (Ed.) with Wu Tsang & Enrique Fuenteblanca (2025) Theatre Picasso London, Tate Publishing,10 – 21.

This may be slim evidence to use so much about what Bizet’s Carmen tells us about the representation of marginalised communities as a way in to the discussion of Picasso works themselves, as Jones implies by ‘gossipy’ but it works for me and I can’t wait to both see the clip and see how performance artists relate the content of flamenco to the content of some canonical Picasso pictures. Graves explains to the curating artists that:

… I want to speak to the ways in which the mythologies around flamenco become an interplay between people coming from the outside to watch it, and in part attempt to describe and define it, versus the people who are actually taking part in it and whose experience might speak to something completely different to what’s being described from the outside.[5]

That long sentence feels like music to me despite its length and, by some standards, irregularity. It sets the function of the artwork as a continuing negotiation between the external viewer and internal viewed, especially the viewed represented human figures within the artwork’s represented queer world and the human gaze that tries to comprehend them and their alien circumstance. And that is what sets my intellectual / cognitive/emotional expectations of this show – without at this point knowing how the exhibition will ask me to collaboratively act with it, collaborate with it physically and bodily.

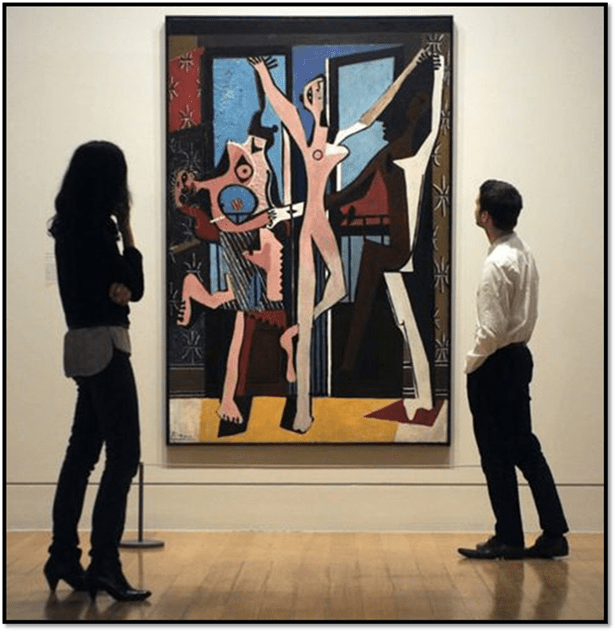

And even before seeing the show, I feel invited to think again about The Three Dancers (and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon – in full knowledge that Avignon is not primarily the French city but a street in Barcelona where there was a brothel). Let us look now at the former of these in a photograph of it and some viewers enacting or performing the role of relating to it.

If gazing at a painting is a ‘performance’ (or performative act) it scripts certain gestures, stances and scripts (even when we silently gaze and speak internally to some subjective other) , often in an art gallery it involves some static pose, at least temporarily although we might vary the point of view it offers of the painting by coming nearer to, or retreating further back from, the object. And one of our tasks will be to wrest the figures from their visual context or in some way find how these relate to each other. Hallett in the i newspaper and Jones in The Guardian reviews actually do some of this work inadvertently, and rather well in saying the following – better together than as single comments within their critical descriptions:

Its title is deceptively simple: three dancers, two of them certainly female, are framed against an open window, the brilliant blue of a Mediterranean sky behind them. But each of the dancers is uniquely strange, and the picture shifts restlessly between the violently joyful, brutal, portentous and serene.

____

It’s like a stage set, a room with a view, except beyond the windows, which are weirdly opaque, is only a blue Mediterranean sky of hard pigment suggesting unbreathable air. Life is a theatre, this painting suggests, where we move among fake furniture in an illusory set with no freedom or space,

The people in The Three Dancers unleash themselves in Dionysian frenzy. The woman in the centre flings her arms in the air as she raises her head to the sky: … On the left, a woman gyrates even more ecstatically, twisting over so that there seems to be around hole showing dead sky where her heart should be.. Her face has the empty nose socket and eyes of a skull. On the right, a male dancer has a partly brown, partly white body, ….[6]

They are better together these commentaries because both read alone slip onto certainties unavailable to anyone who reads them together. Both indicate an artifice that governs the whole both in the word ‘framed’ in Hallett and in the extended theatre set simile in Jones. However, Hallet wants to see the real sky that the picture represents and both are too certain about the stability of the sex/gender markers in the figures (in Jones he is certain of all three of them and therefore does not question his judgement of who is ’she’ and who ‘he’). It is not a stability he finds in the race / skin colour markers . Moreover, they both fail to see that the movement they both perceive in the picture is entirely an effect created between the viewer and their attempt to perceive the relations of figures to their ground. Jones is bizarre in writing of a ‘hole showing dead sky where her hear heart should be’ as if it were an illusion created by the figure (‘twisting over so that there seems …) as if had they not twisted in their dance, we might never have seen such a hole. However, that hole is not a product of motion any more than is ‘the hard pigment’ that suggests ‘unbreathable air’. All paint of whatever pigmentation dries harder than in in its fluid form, however initially viscous or not, so what is meant by a ‘hard’ pigment – how does it differ from a softer one?

Both critics still I think rely on the equation of the painting with the iconography of The Three Graces in Renaissance painting, though Jones suggests that these women/men might be Bacchae by speaking of Dionysiac frenzy. Is this suggestion only an effect of phrasing that uses cultural reference to indicate extremes, or does he mean that these women (if they are all women) are a danger to the patriarchal order like those in Euripides’ The Bacchae? I feel satisfied that we cannot answer these questions – not even that of whether there is a reference in this painting to the death of Pichot, for shadows (of all kinds but not less those caused by artificial and directed intentional lighting effects) are classically illusions of theatrical form and techniques.

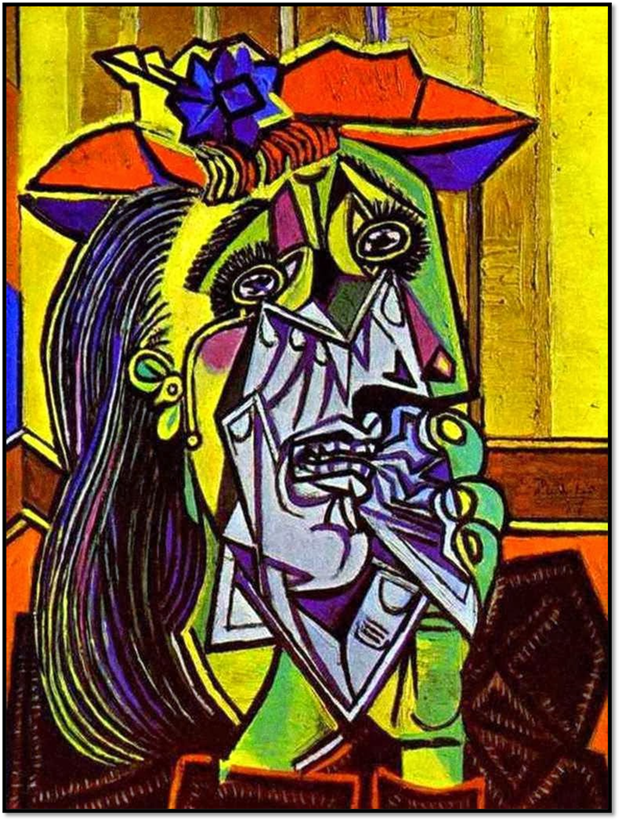

When I go to this exhibition I want to see how the curation of the exhibition situates me as a viewer, who is, in Graves’ excellent sentence ‘coming from the outside to watch it, and in part attempt to describe and define it, versus the people who are actually taking part in it and whose experience might speak to something completely different to what’s being described from the outside’. For this will be me, finding it as difficult to relate to people whose subjectivity may differ from what, on the outside, I am able to see. But how is that interior experience to be performed. That is a question I can easily ask of paintings by Picasso like The Weeping Woman, which his misleading named a portrait of Dora Maar – for it contains what look like Picasso’s hands performing as a woman in the light of the Nazi airplanes bombing Guernica that they cannot make themselves stop seeing – so real so performative on inner and outer, female and male in transition.

Now the catalogue tells us unequivocally that the relation of Picasso to ‘performativity’ will employ many extant meanings and uses of that term relating to ‘a concept with multiple meaning and theoretical developments’, starting with the use made of the term by philosopher J.L. Austin in How To Do Things with Words to Judith Butler on, amongst other things, sex/gender. But their point is that Picasso chose throughout his career and in many stylistic periodisations of his manner of doing things with paint, and eventually other materials, like newspaper print, to show to viewers the hard to enter areas, especially the bodies that obsessed them and what this exhibition calls marginalised and ‘subaltern’ bodies. But that does not exclude simpler meanings of the ‘theatrical’ – from those already in straight art history that study his involvement with Diaghilev, the Ballet Russes and scene and costume design and play-acting.

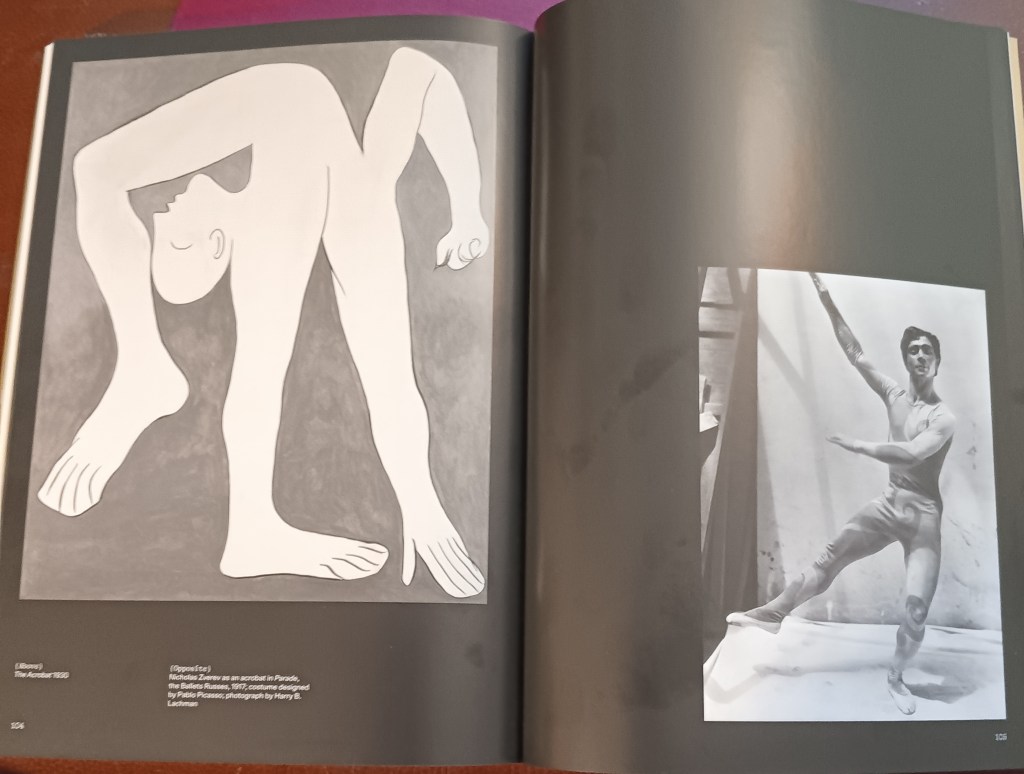

They study masking across boundaries of culture (the real reason for his interest in African dance ritual masks) – such as animal-human , male-female boundaries. he studies show-people such as acrobats feature and the flexion of their performing limbs drawn in impossible patterns of body motion and tension:

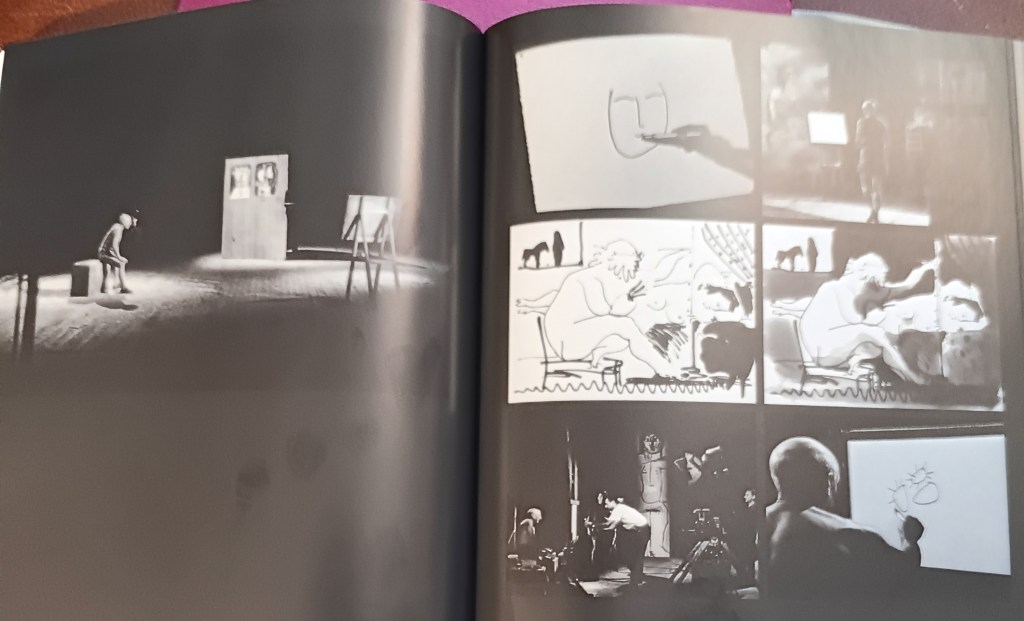

He even includes the exhibition argues the artist interacting in a studio set with a model, with reference for Picasso always to Balzac’s The Lost Masterpiece, and the static or not so performance of a seated woman or the visible (and sometimes cunningly filmed) action of his own drawing.

Again much of that comes down to The Three Dancers, read through the lens of the historic emergence of the contradictions of flamenco, torn between classic (danza) and subaltern forms (baile).

Jones, as is his wont, rather simplifies how the modern artists curating here do this. To him, it all boils down to an exhibition that is:

“staged” rather than curated, … in a series of cabaret and theatre-like spaces they hope will give visitors a “rhythmic experience”. Picasso says Tsang anticipated “the fluid relationship that artists have with performance”.[7]

Jones almost put scare quotes around Tsang’s’ words to show his distance from such faddishness, but at least in this review he doesn’t articulate that awful self-positioning. My own anticipation now couldn’t be higher, this is an exhibition that will test me and the theories of its stagers, and I intend to dive a bit deeper into myself than Jones ever allows himself to do. One example really grips me – it is the exploration we are led to expect of the relationship between the ‘obscene’ (dramas of sex and death too visible for some) and the theatrical – the ‘scene’ on obscene. The catalogue says these are always framed images in a scene or fluid set, that might be a brothel, beach or a drawing-room. The catalogue picks out Nude Woman with a Necklace (1968).

The picture shows a turning female body but it leads the gaze down to a stream of urine that pours into the background of the figure becoming the context of its exterior setting, a wave of the sea about to break over her. As a staging of the inner and outer (all in changing aspects), it is unsurpassable.

I cannot wait to see this exhibition.

Next blog in this series is on The Bacchae. There will be crossover.

With love

Steve PS I will report back after visiting.

[1] Cited Rosalie Doubal & Natalia Sidlina (Ed.) with Wu Tsang & Enrique Fuenteblanca (2025: 57) Theatre Picasso London, Tate Publishing.

[2] Pedro G. Romero (2025:28) ’Above from Below: Declassing Picasso’ in Rosalie Doubal & Natalia Sidlina (Ed.) with Wu Tsang & Enrique Fuenteblanca (2025) Theatre Picasso London, Tate Publishing, 22 – 33.

[3] Patricia Leighten (2025: 35) ‘Picasso, Anarchism, Primitivism’ in Rosalie Doubal et.al., op.cit. 34 – 42. Leighten is also the author of the 1989 Princeton University Press publication, Re-Ordering the Universe, Picasso and Anarchism, 1897-1914 and the 2013 volume from Chicago University Press, The liberation of Painting: Modernism and Anarchism in Avant-Guerre Paris.

[4] Jonathon Jones (2025: 34) … A new exhibition explores the theatrical side of this uncompromising artist’ in The Guardian Weekend Supplement, Saturday 30th August, 34 – 36.

[5] Yinki Esi Graves(2025: 52) cited in ‘Yinki Esi Graves in conversation with Wu Tsang and Enrique Fuenteblanca’ in Rosalie Doubal et.al., op.cit. 50 – 55.

[6] Florence Hallett (2025: 38f.) ‘The day Picasso won over Britain’ in the i newspaper, Thursday 18th September 2025: 38 – 39 & Jonathan Jones op.cit: 34 respectively

[7] Jonathon Jones, op.cit

8 thoughts on “What could I do more of? I could allow art and ways of seeing it to challenge me more: a preview of what I expect from the ‘Theatre Picasso’ exhibition at Tate modern, which I see on October 21st 2025.”