How do you plan your goals?

Let’s unpack the question today, for it is culture-defining. Behind it lie three assumptions about modern humanity:

- That human beings follow rational ends or purposes – things they normally call ‘goals’, and that these goals are self-defined.

- That human beings constitute the main agency of achieving goals by planning and working upon these plans. There is always a spanner in the works. What if achieving your plans is, in your self-interest but not those of other humans, or indeed non-human animals, with agency? In those cases the agency of others that in anyway blocks or frustrates your plans must be minimised (optimised is perhaps) the word -if it cannot be eliminated. You will see this in the rationale of current day Zionism where radicals are eliminators.

- That it is the consciousness of individuals that are primarily in control of their own agency through planning decisions

The study of goal-orientated thinking arise in the history of philosophy arise from rather mixed sources in defining the paradigm that we call teleology. Originally the issues it covered stemmed from core or foundational beliefs that things, in order to definable as things, had a predetermined, or even ‘natural’ purpose or end. That end could not be determined by an individual but belonged to the intentions behind the role of thing in its creation from ‘no thing’ by God. Those intentions equate with the forms of the thing that pre-exist it in Plato’s philosophy, and have divine origin. Thus, as an aspect of metaphysics (but leaning into politics and ethics) in philosophy, we attribute to Plato and Aristotle, respectively, the standard definition of the causes of things and events based on the achievement of their divinely-given purpose or goal. Let Wikipedia help us out on the word’s meanings and usages:

Teleology (from τέλος, telos, ‘end’, ‘aim’, or ‘goal’, and λόγος, logos, ‘explanation’ or ‘reason’)[1] or finality[2][3] is a branch of causality giving the reason or an explanation for something as a function of its end, its purpose, or its goal, as opposed to as a function of its cause.[4] James Wood, in his Nuttall Encyclopaedia, explained the meaning of teleology as “the doctrine of final causes, particularly the argument for the being and character of God from the being and character of His works; that the end reveals His purpose from the beginning, the end being regarded as the thought of God at the beginning, or the universe viewed as the realisation of Him and His eternal purpose.”

A purpose that is imposed by human use, such as the purpose of a fork to hold food, is called extrinsic.[3] Natural teleology, common in classical philosophy, though controversial today,[5] contends that natural entities also have intrinsic purposes, regardless of human use or opinion. For instance, Aristotle claimed that an acorn’s intrinsic telos is to become a fully grown oak tree.[6] Though ancient materialists rejected the notion of natural teleology, teleological accounts of non-personal or non-human nature were explored and often endorsed in ancient and medieval philosophies, but fell into disfavor during the modern era (1600–1900).

In Western philosophy, the term and concept of teleology originated in the writings of Plato and Aristotle. Aristotle’s ‘four causes‘ gives a special place to the telos or “final cause” of each thing. In this, he followed Plato in seeing purpose in both human and nonhuman nature.

Wikipedia continues with a relevant etymology:

The word teleology combines Greek telos (τέλος, from τελε-, ‘end’ or ‘purpose’)[1] and logia (-λογία, ‘speak of’, ‘study of’, or ‘a branch of learning’). German philosopher Christian Wolff would coin the term, as teleologia (Latin), in his work Philosophia rationalis, sive logica (1728).[7]

Etymonline.com can supplement that again as our source of information on the word which has the following (an edited version below):

Origin and history of teleology (noun): n.)

“study of final causes,” 1740, from Modern Latin teleologia, coined 1728 by German philosopher Baron Christian von Wolff (1679-1754) from Greek teleos “entire, perfect, complete,” genitive of telos “final end, completion, goal, result” (see telos), + -logia (see -logy). Related: Teleologist; teleological; teleologically.

telos (n.) : “ultimate object or aim,” 1904, in biology, from Greek telos “the end, limit, goal, fulfillment, completion,” from PIE *kwel-es-, suffixed form of root *kwel- (1) “revolve, move round; sojourn, dwell,” perhaps via the notion of “turning point (of a race-course, a field).”

-logy: word-forming element meaning “a speaking, discourse, treatise, doctrine, theory, science,” from Medieval Latin -logia, French -logie, and directly from Greek -logia, from -log-, combining form of legein “to speak, tell;” thus, “the character or deportment of one who speaks or treats of (a certain subject);” from PIE root *leg- (1) “to collect, gather,” with derivatives meaning “to speak (to ‘pick out words’).”

*kwel-(1) : also *kwelə-, Proto-Indo-European root meaning “revolve, move round; sojourn, dwell.”

Of course that is all interesting in itself especially given that a possible root word from PIE (Proto Indo-European) is a world relating to the revolving action of a wheel, and hence turning point and perhaps even its contribution to the word ‘wheel’ argued by some. It is precisely though these older meanings that the modern associations miss out when thinking of teleology, using in the ugly phrase: ‘goal-centred behaviour’. This may explain the fact that etymology has increased in frequency of use in modern times, actually increasing at faster rate again in 2019 according to a Google no-gram (though caution has to be used in its interpretation, and not only because of the reliability and validity of the method of measurment:

Plato and Aristotle (at least in his fourth set of causal agents, tended to link those to the stabilising effect of Final causes – that argues that everything develops to fulfill its nature, and that such natures are not the sole domain of humans but also Gods (animals don’t get a look in except as analogous relationship to humans as that of Humans to Gods). Everything revolves of the most final of final causes – an idea that became that of the Primum Mobile, the First Mover whose causative agency is the creation of all things in their pre-determined nature – which Aquinas had no trouble in identifying with the God of Judaeo-Christianity.

By 1880, the human world was much more ready to abandon God as a ‘final cause’ of things and look to human agency in shaping the world – with peculiar concentration on creative or inventive individuals. And that agency abandoned too other aspects of cause, including irrational (or non-rational) ones, or ones that proceeded from the interaction of many agencies proceeding from different domains. The invention of Psychology as a disciple aligns with this, together with its stress on the individual self.

Practical or applied psychology went into overdrive to convince people that only they could be the final arbiter of success in the fulfillment of goals, irrespective of other forces. This was the fuel not only for a culture honouring individual,success over the mass of indifference meeting a person’s assertion of goals, but a guilt culture blaming individuals for the errors in their planning, attributed to deficiencies of both thoughtfulness and work to drive their thought into effective action, for their lack of success in the world or their own lack of fulfillment or happiness.

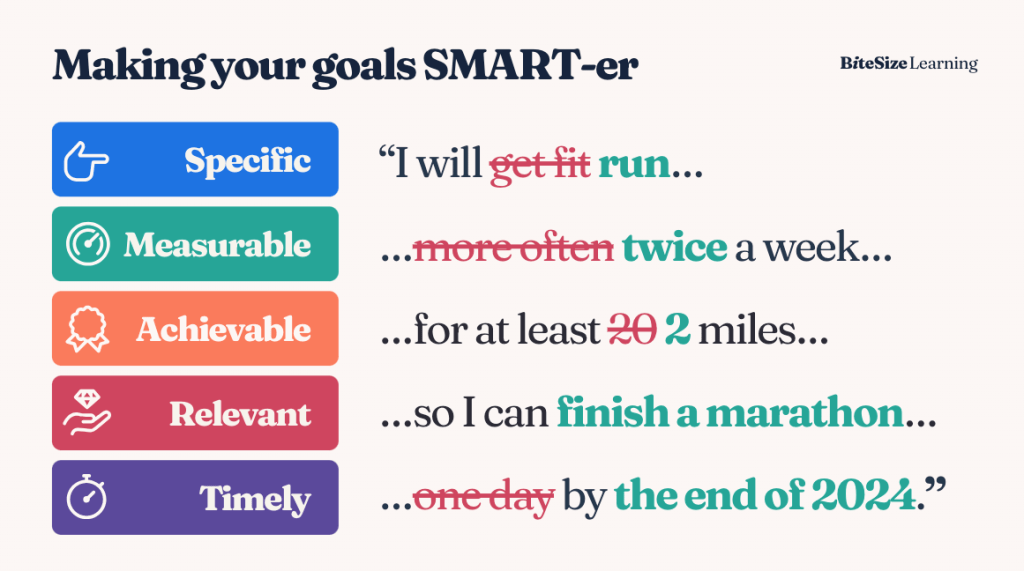

Despite disclaimers that is still the language of psychological intervention – aiming at rendering planning more effective and tying success in that to the chances of success in the person’s goals. God forbid you have ‘fuzzy’ goals – they must be SMART ones. The word ‘smart’ is meant to set against ‘dumb’ goals – to impel people to side with their right to be considered intelligent but it was an acronym for setting and planning only goals that are::

SMART is an acronym that stands for:

- Specific: Goals should be clear and specific, answering the questions of who, what, where, when, and why. For example, instead of saying “I want to get fit,” a specific goal would be “I want to run a 5K race in three months.”

- Measurable: You should be able to track your progress and measure the outcome. This could involve quantifying your goals, such as “I want to save $5,000 in the next year.” This allows you to see how close you are to achieving your goal.

- Achievable: Your goals should be realistic and attainable, considering your current resources and constraints. For instance, setting a goal to “increase sales by 20% in the next quarter” is achievable if you have the right strategies in place.

- Relevant: Ensure that your goals align with your broader objectives and values. A relevant goal should matter to you and fit into your long-term plans. For example, if your career goal is to advance in your field, a relevant goal might be “attend two professional development workshops this year.”

- Time-bound: Set a deadline for your goals to create urgency and prompt action. For example, “I will complete my certification by the end of the year” gives you a clear timeframe to work within. (AI generated definition by Bing)

The goals can’t have multiple facets or varied or even ambivalent meanings. they mus be ‘clear’, with the word ‘concise’ attached. Anything else absorbs attention from focused thinking and energy from focused action based on that thinking. If there is automaticity involved in the process, there isn’t inn the plan which will include flexibilities based on initial failures to meet the goals involved. Its not ‘foolproof’, for it can’t be operated effectively by a ‘fool’, which is someone who fails to keep meeting their goals as their priority of thought and action. Indeed the reason it does not work, its adherent says is precisely because the Goals are Foolish (fail to meet these criteria) and the Action Ineffective (because not matching the needs identified by the Plans towards one’s goal). Sometimes you are obstruvted from meeting your goals by the self-interest of others, If these others are very powerful, the goal is dropped as ‘unachievable’. If not they must be swept away from the scene.

So that’s the question unpacked. I just don’t see persons, life or the world as like that. I can’t answer:

How do you plan your goals?

As for an alternative to how to live your life – well that is why moral philosophy is such a complex thing.

One thought on “The limits of telelogical thinking with or without the concept of personal agency.”