It is almost compulsory to describe the effect of art as achieved ‘beauty’. We use ‘beauty’ too often in this respect. The words that come to me as I reflect on an attempt to reconnect with the art of Andy Goldsworthy are precarity, structural fragmentation or decay, fragility and ephemerality, so how has his lasted and strengthened its hold on us over 50 years: This blog is based on a visit to the National Galleries of Scotland’s exhibition Andy Goldsworthy: Fifty Years at the Royal Academy Scotland on the 11th August 2025 at 11 a.m.

I left the James exhibition thoughtful. How do you retrospect on the 50 years of a career that has always made the impossibility of endurance over time the main subject of its artworks. Most of the retrospective of works cannot be seen ‘in the flesh’ as art historians like to say (a phrase I once reflected upon in a blog on a book by Martin Gayford at that link) and are represented in photographs or video film, such that these ‘records’ of his art are in danger of becoming all there is of that art. It is an issue that first troubled me about him, looking at his works in the process of decay and fragmentation in The Yorkshire Sculpture Park, for instance. So troubled was I that when I culled my library to the much slimmer for of 4,500 books or so, his were among the first to be moved on.

I had decided that I no longer wished to engage with this work, partly because for me it had turned only into the conceptual work it evoked. I decided that though I still wanted to see this retrospective – to check on the tensions that he raised in me, only to find them raised again – a conceptual insistence that I felt upon attempting to gaze these works that I stopped being capable of looking, racked with a kind of acedia of the eyes, mind and emotion. I hate such feelings. They feel to me like despair. I had decided though not to buy the rather beautiful looking catalogue and relied only on the free guide (my opening photograph shows it that holds a picture of Andy imprinting his shadow on the pavement of Prince’s Street (southside) just outside the Royal Academy’s entrance – a shadow bound to disappear soon, and a fine emblem of my feelings about him.

In that document Goldsworthy records this in honour of the records of his earlier work in Room 9, thinking back to his first year at Preston Polytechnic, based at ‘nearby Morecambe Bay’. He says:

One day, early in my first year, I took a spade onto the beach and started making marks. Art has made me look at the world, understand the world; it’s made me see and engage with what’s around me. Looking back at these works I can see that all the things I am interested in now were present in the work I made 50 years ago. The passage of time, chance, risk, engaging with the land’.

The permanence he sees here is conceptual and not that of the works themselves, which barely can be represented by these reproductions of a flat vision of them, seen without even the haunting need to touch the works, a thing the notices frequently dotted around the exhibition prohibit, if done in the flesh at least.

Before I read the paragraph above I had jotted down the words that came to my mind as I walked around this show trying to feel but only managing to think about the art – hence my wors are more Latinate and abstract – a bit how the art makes me feel. They are:

- Precarity – registered in the making of marks on fragile materials, including the unpredictable nature thereof, or the attempt not to make such marks (as in that famous work that consisted of the artist crawling through hedgerows);

- Structural breakup, either as a result of:

- Accidental fragmentation, or;

- Decay – some partial process of dying.

- Fragility of the whole work or parts of it that change its expressive potential and / or structure, and;

- Ephemerality – in its physical being, meaning or emotional charge. This latter emphasis is really present in the early work (in Room 11) he has generalised his records of, under the name Snowballs.

Sometime PRECARITY is an aspect of the artist’s self-placement in the art. In that video record, for instance of him making the art by crawling slowly, in order to maintain precarious balance, across ranges of hedgerows outside the time of foliation, so that they structure provide empty spaces of passage of his body, if, at least, he was careful, and enough rudimentary structure to bear his weight.

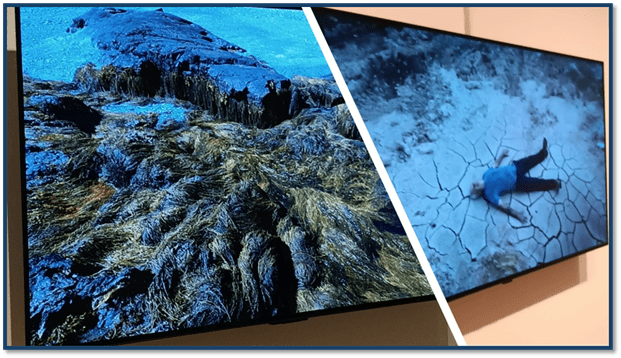

At other times precarity is posed by the flimsiness of part of his materials that also tended to make the marks his touch upon it (sometimes his full body weight through his boot) unpredictable and non-enduring as in crusts of all kind, including ice covering or the cracks in dried surface mud. In the item on the right of the collage below, the body of the artist lays as if it has fallen and was the cause of the stress marks on the surface.

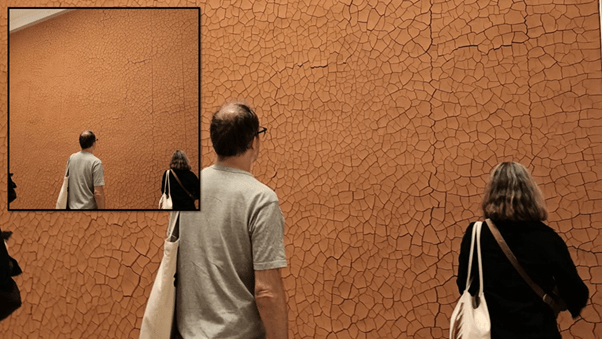

Yet the interaction of things on earth over time, let alone the interaction – accidental or planned of human and raw material causes changing patterns of flow, direction of obstruction touched by that flow and causing it to move. The film on the left is of the ebb and flow of the sea on coastal sea foliage causing difference in the flow potentials for the sea as it itself moves the stronger foliage to a different position. In a ‘live’ new piece called Red Wall (2025) red earth from the Lowther Hills the earth, refined of rock material, is applied as a surface to a wall, drying variably and in relation to its variations of thickness and cracking – sometimes regularly, sometimes not. The interaction that causes marks is indirect to the agencies which make the art, but it reveals precarities in longer cracks that appear to be about to shift the material from the wall.

Sometimes the precarity is planned effect of relationship between realistic figuration of sculpture and craft construction (from dry-stone-walling to modern road building) where the sources of our feeling of precarity is about danger to the figure – even though we know the figure to be only a realistic representation made surreal by its failure to suffer from what it is experiencing:

The variations of such precarity are endless in walls of photographs of its instance. Do we fear the effects of gravity that has suspended activity so the figure does not fall as we believe perceptually it should or are we aware of other contextual danger – from inclement weather to the passing of a car too fast and too near these figures.

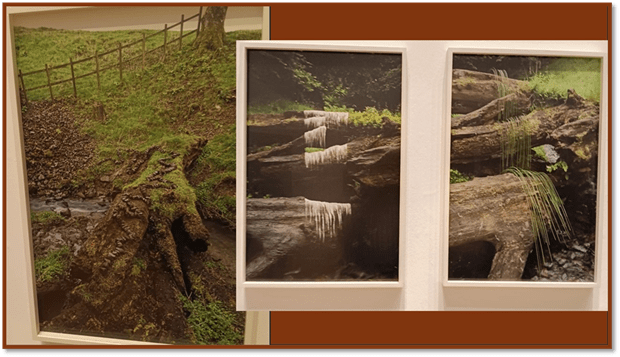

Structural breakup has already been shown as an effect of precarity above (in Red Wall for instance) but sometimes it is a function of both the risk of accident and the effects of interactions occurring naturally in time, or a representation of both of those things. In such situations we find what we seer hard to interpret perceptually and the variations it shows from what we might have been expecting to see in its location even harder to tie to a cause – of chance muddle of materials, artistic manipulation or effects of incidents of placement of unknown or random cause. Look at the examples below. Are there bridges built on purpose to transit risky gulfs or waterways in a landscape or moulded artefacts with an intentional meaning beyond their function. Or is the interpretive work, an accident of perceptual psychology that is at least partly beyond our control.

I don’t know how to show how these effects arise in each of the recorded instances (of art long since decayed back into its landscape setting) except that the item down at the left of the second collage above that might be either an intentional bridge to a beck or a tree fallen over that beck and worn and decayed, or have been cut and shaped (perhaps to act as a bridge or by an artist looking for other effect) has the look of a severed hand grasping the soil – even digging into the earth (perhaps to save itself. The fallen trees over a gully are strewn with threads might represent water flow, Nothing in our interpretations has structural or evidential weight, can breakdown – is interpretively precarious. A shape or prints can seem to be marks crossing such structures but are they, or accidental damage or fungal growth.

The fragilityof the materials in a structure or in some of its parts is vital to some works – one video shows the boot of the artist progressing over a fragile surface of ice, fracturing it, and there are many versions of this kind of ‘accidental’ exploitation of fragility to create pattern that might temporarily be experienced as beautiful – till the whole surface structure melts thus broken up and at risk to heat that destroys it. But some human structures depend on fractures in materials – and even are moulded by such fractures. If you place that next to a hand covered in redding material – almost certainly natural, then the violence of the appeal of fracture becomes associated. See the video (stilled) on the left in the collage below. The effect is of a discovered murder.

On the right above the artist is covered in black mud that disfigures his body shape into hard to interpret hangings but also stains the skin and hair variably. Such a man seems fragile, helpless but also somewhat threatening. Certain interpretation avoids us.

And, of course, all these effects are ephemeral. The marks will dry, crack and fall away or be washed off or otherwise erased – by effects we call those of time but involve various interacting agencies – weather, wear, use or disuse or so on. I deliberately neglected to read the explanation of the art work below, for on first glance it may seem that there is no art work – and even now I am guessing what it is.

I want to see the art in the brown tree-like structure in the middle of the landscape, that has the colour of rusty iron. Is it constructed, painted (or covered by red earth – the iron earth that is so like blood in Goldsworthy’s view and conveys the associations between elements of body and earth. The effect is necessarily ephemeral – if lengthened in duration in photography from which 50 year retrospectives can be made.

Another work (in Room 1 called Gravestones) evokes death in its name and is the laid remnants of fractured rocks. Yet these rocks are not destroyed gravestones as you might suspect from the title but fractured stones recovered from those displaced by human ‘burials in 108 graveyards in Dumfries and Galloway’ by the artist and his son, Joel. Do these rocks represent fragility or rather how the collectivity of ongoing life that reassembled them, however accidentally in part, purposively in other parts. The whole thing bruits ephemerality as much as Gray’s Elegy in a Country Churchyard.

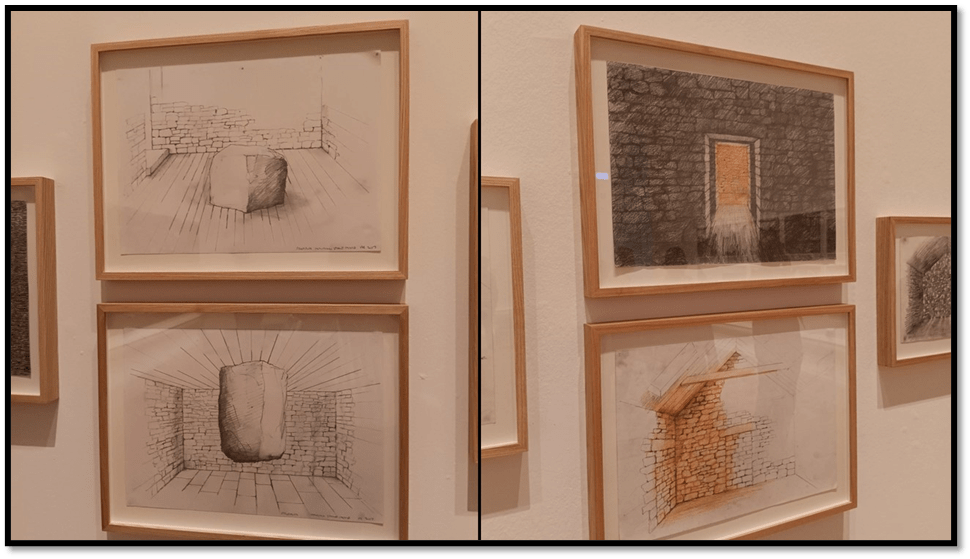

Drawing, of course, is a medium we often associate with beauty, and though often the method of temporal ‘studies’ for a larger work, as were those for a project based on the rescue of buildings in Hanging Stones Lane and Hanging Stones Farm, near Rosedale Abbey in North Yorkshire, they associate with the temporal nature of human presence in the area – whose remnants are shaped and placed materials and marks like paths and access points like door. These drawing play with durability however that cannot or never existed, that claim to defy ephemerality whilst emphasising stolid resistance to human presence.

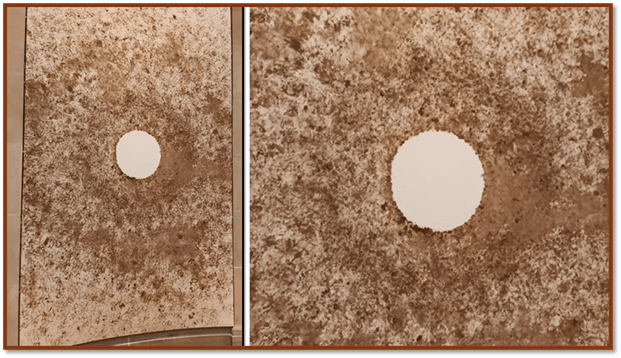

Some other work seems focused on intentional symmetries, and is hard to think of as other as intentional, but is anything but. I remember an earlier version of this work being covered by the mainstream media where its genesis was filmed. Called Sheep Painting (2025) here – for it is a new version – it is literally ‘painted’ by the hooves of sheep from the fall of mud on their hooves. The canvas is:

nailed down in a field. A mineral block placed at the centre. The sheep feed off the block, bringing mud onto the canvas. The number of sheep in the field, how hungry they are, and weather conditions all have a dramatic effect on the outcome of the painting. … After a few days the mineral block is lifted – revealing a circle of white untouched canvas.

The effects of contingent events and factors matter clearly but the painting reveals a kind of pattern of concentric circles, presumable created by the placing of four hooves at each ‘end’ of the sheep’s similar-but-not-the-same lengths as they lick the block. That the sheep vary and that areas of concentration of approach are determined by other factors impossible to recreate in mind from the work itself explain the variations that make the underlying concentric pattern vary too in a way that you might here be forgiven for seeing as ‘beauty’. But no-one intended beauty – least of all the sheep. The pattern builds as marks accumulate contingently over the time and patterns that would have been on the field’s surface anyway are rendered visible, and to some extent durable. But are they not by nature ephemeral – however we might ‘varnish’ them into temporary stasis.

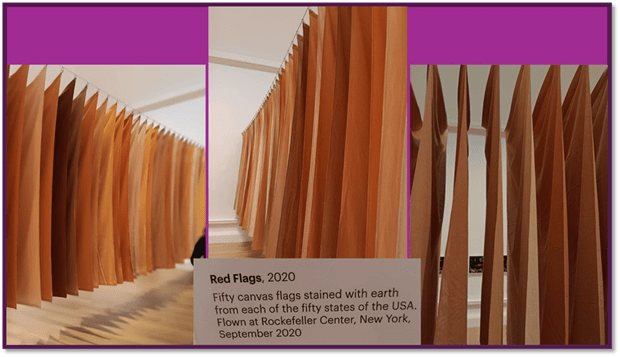

One work is extremely intriguing because it represents political contingencies that will vary named Red Flags. Lent to the exhibition by the Scott Mueller Collection, USA the flags once flew on standard flagpoles outside the Rockefeller Centre, used to housing the flags of differing nations, often ones in contingent conflict. The 50 flags were each stained with the natural ‘reds’ (that of course vary) in soils from each of the respective States of the union they represented. But ‘red flags’ are not neutral – try as they might to represent as Goldsworthy says to ‘transcend borders’ emphasising unity and ‘connection not division’, thee name is stuffed with association in American history and in the place, in it of the creation of an internal ‘Red Meance’ to cement the federated nation’s current fragile contentions over the meaning of land. Whose land is this? Is still a dividing thing in American – the colour Red also associated with the insulting name by which Native Americans were once known, ‘Red Indians’, where skin colour is a mark of double displacement – these are not even ‘Brown Indians’.

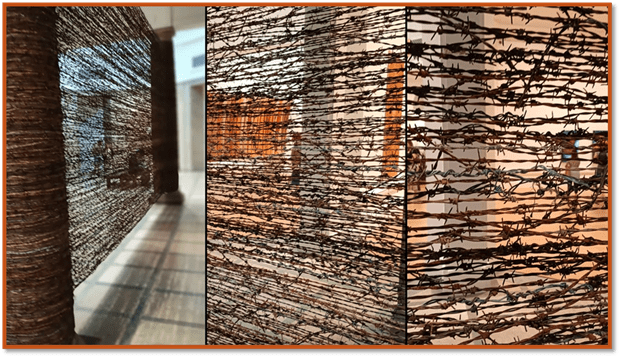

I don’t think ‘beauty’ covers all this at all. Let’s take a work that still fascinates me in memory: Fence (2025). Goldsworthy associates the barbed wire out of which Fence is fashioned with the aggression over the limitation of land to ownership: the barbs might claim to be weapons to discourage sheep from escaping, they often are mounted against the entry of persons to a ‘land’ they too might feel entitlement to if not ownership. Conceptually it is spot on. It is the one work, paradoxically, I found ‘beautiful’, if fearsome. The aggressive nature of the barb is even greater than that landlords achieve, in its use of ‘beautiful’ crossovers.

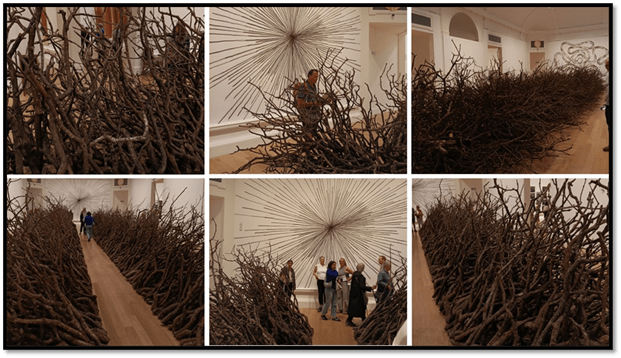

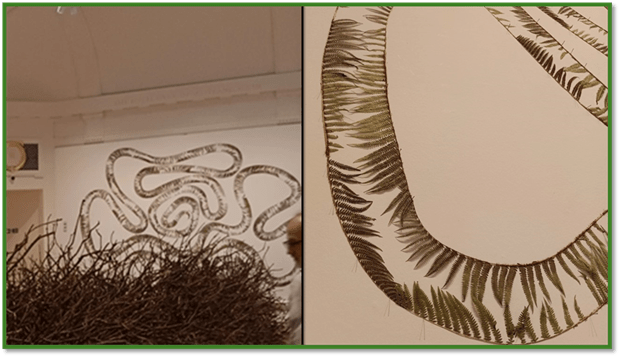

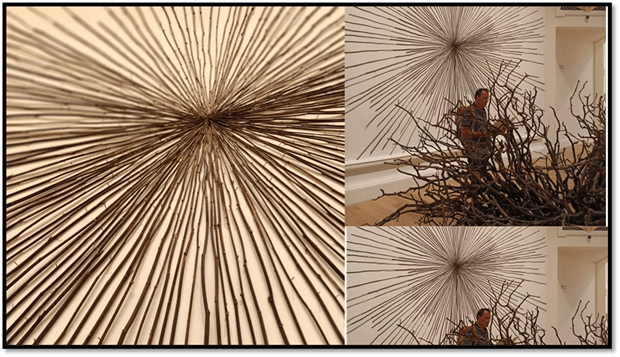

But let’s linger with what the curators, and perhaps Goldsworthy too, would consider his key statement of this exhibition in Room 5. The room is first perceived as containing a central fairly impenetrable barrier of closely matted oak branches that were collected from wind damage, with two different configurations of natural materials in fictive shapes at either end. Only as you approach either of the latter do you find the two wonderful wall patterns are connected by a walkable passage between two parallel lines of oak piles.

Those end pieces are the nearest approach to beauty in the place, and even over-reach that word. At one end is a patterned drawn line, perhaps of an organism – a tapeworm might be suggested but also a kind of intervolved passage to a nowhere but staying within itself, from which there is no escape. Within its borders. as we get close, we see it decorated with green-brown fern (the colour suggesting decay, but also the life of the parasite I imagine.

On the other wall, more wind blown twigs are formed into an irregular concentricity that reminds of the Sheep Paintings we see at the entrance.

Now there is beauty. It is beauty that must be disassembled and then what? Maybe that doesn’t matter, for each form of the passage of a work oft may be beautiful and meaningful in another way, but it reminds me that this work will soon be one that we cannot, as it is, see ‘in the flesh’ again. And therein lies the pain of Andy Goldsworthy’s work for me.

Given another chance to buy the catalogue I didn’t and even now, given writing this blog has aroused my interest in the artist again, I do not regret not having books recording him in my library. As I left the exhibition, on my way to Sunday events at the Book Festival, there was no retrospective joy in me but a sort of empathetic dullness – a sense of art that undermines art too successfully for my soul to bear the pain. Fortunately I had Kitamura and Brown to look forward too.

But do see the exhibition. It stuns. But don’t stop short your responses by looking primarily for ‘beauty’. It is an over-used word.

With love

Steven xxxxx