Future plans are a kind of ‘bridging project’ for possible migrations. This blog is about naming the space we travel through in the art of Do Ho Suh. It reflects on visiting the exemplary exhibition at Tate Modern, London Bankside, on 9th July 2025.

“But what exactly do you mean by space?” I remember the first time an art history tutor first used that dreaded question as a launchpad to attack the wooliness of my essay structure on some form of visual art. The term ‘space’ can be easily invoked as a descriptor of the three dimensional artefact that can be validated by either measurement or an illusion of the thing in all its dimensions as something whose meaning depends on the conditions of perception, both external and internal to the viewer and perhaps of a different realm or differing realms of ontology. Of course, any object must have at least three dimensions, even a painting, since the materials on which the painting is painted and the paint itself have each a thickness or depth that can vary tremendously. The notion of painting as two-dimensional is perhaps in itself imprecise, and we cannot ignore the actual depth of the media that constitute the thingness of the painting before saying that, otherwise, it has entirely non-measurable spatial dimensions. Some speak of a four-dimensional understanding of artworks in which the time of both looking and changes in perspective of the thing are part of the effect – though only the ones that cannot be measured in a standardised manner.

It is clear though that you cannot talk about art without invoking the concept of ‘space’, even though so many things can be intended by speaking of it even with specific artistic modes – many of the spatial issues evoked to describe architecture are as much about the psychological illusion of space as about the things in a constructed artefact with an interior and exterior that can be precisely measured by common standards across three dimensions. Whether time – measurable or otherwise – can be spatialised as a concept will depend on whether we are describing something according to its abstracted Euclidean geometry (however irregular that geometry it can never change once abstracted) or its appearance across a range of possible ways where we sense space as a thing, substance or solid. For substance, things and solids are always potentially in the process of change, not least as a result of being seen by a variety of seers or the same seer from necessarily different points of view across the possible co-ordinates of expressing that point of view. That, at least, is my understanding of the philosopher of mind, J.J.C. Smart’s, 1955 essay on Spatialising Time.[1]

Artists however, do not expect to be held to account in this way by this or any other kind of philosophical narrowing of discourse and I will not attempt to do that in reflecting on my experience of the Do Ho Suh exhibition at Tate Modern. The reason for that is not because the artist is superior to the clarity aimed at by philosophers of space and time but that their understanding of experience is never ever about clarity of consistent definition but the density, intensity and opacity of what occurs in lived time and space, as well as its co-ordinates in things that have standardised measures.

Of course, ‘density’, and perhaps the other qualities may be considered measurable in some definitions, but not in the stuff needed to allow us to conceive, plan, execute and reflect back on art from different perspectives. In the catalogue for this exhibition Janice Kerbel in conversation with Do Ho Suh invokes the logic of art and experience to describe place in Homer’s The Odyssey in order to open up what ‘space’ might mean in the artist’s works and how that meaning might change across time:

…, I think what your work does very successfully is exist between states. At the beginning of The Odyssey, the question is asked, “Where did this take place?” and the answer is: “Somewhere between sunset and dawn”. … The collapse of time and space is often happening, but not always obvious.

The artist answers thus:

My work is not really about replicating a physical space in a physical material. I’ve actually dreamed, literally dreamed, of making something out of smoke – out of nothingness. But we live in a three-dimensional world, and I quickly learned that I had to work with gravity and materiality. Still, these are works that are about memory, about feelings, about energy. And actually what I have been doing is not just to transport spaces into different places, but also to incorporate time in a physical piece.[2]

Even the catalogue itself is a collection of ways of discoursing about space and time.

This occurs in its contents by the use of written and graphic narratives using sketches and photographs and various states in which the same artwork occurred or was deliberately reinterpreted in meaning and process – in the creation, for instance, of greater two-dimensionality in works that once were shown in three dimensions. But there are also more theoretical discussions in which concepts are defined in terms of shift is in time, space and context – the central concepts being ‘home’, ‘journey / walk, passage between binary states likes death and life, male and female, end and beginning in ways that make the binary concept itself unsustainable, ‘bridge’ and ‘project’ (a future tending word after all that invents its own past as it emerges in space).

Howevet, the book is also a materialisation of space and time meanings – its materials are emphasised by their unfinished feel, the exposed binding and the threads within it (threads are important materials in this show and not just narrative threads) – the cover fall back to expose the book’s spine and the threads that aim to make it integral, and then folds out into a continuous flat card until refolded back into book cover format. Much of the book extends the exhibits – described photographically and lexically throughout but mainly on pages 176 to 183 – into their past and projected versions or even states of the exact same work, where space becomes changeable both in its measurable and unmeasurable dimensions.

Strangely, the book disappointed me when I bought it. However, now, in my mind, it is a continually emergent thing of beauty. Some of the ways in which ‘home’ is illustrated defy exhibition in the Genesis exhibition for they are contingent on space, time, resource and sometimes historico-geographical accident. Look at the pictures in the collage below. They speak to their space and time and to ours they announce their temporal and spatial specificity in ways that means they are lost to us other than as the kind of memories that photographs of and by others can elicit – always partial ones (but are there whole ones?). The photograph of a simple house for a poorer culture that has crashed into a larger and more complex structure that can only be owned by someone rich is a case in point.

The houses and homes speak of Do Ho Suh as he speaks of them, existing only on that bridge caused by that conversation, which art can generate. The construction of three-dimensional images of earlier homes, or parts of earlier homes is based, we are told on the development of processes of treating linen or paper to ape solid structure, coloured in ways that were NOT from the original while staying mainly transparent Is the process we see in the imposition above of his Korean ‘home’ space above the staircase of his New York home. He made several hanging (and sometimes inverted) inverted staircases as past three-dimensional installations, often hanging from a cycle with a gap between their ‘foot’ and the floor space used by visitors. It was a considerable gap in the version known as Staircase -III (and based on a staircase in his childhood home with austere associations – it led to the flat of the landlord – at Tate modern in 2011, shown on the left in the collage below. I have here re-photographed a photograph in the catalogue which faces the same piece installed with foot much nearer the floor in Museum Voorlinden in 2019).

The choice of how to Staircase showing the piece in the Gemini exhibition involves a method replicated in other pieces discussed below, which owes something to the concept of flatpack domestic furnishing in modern capitalism. We see it on the right in the collage below. A vacuum drying process of the wetted structure translates Staircase into what we see a structure collapsed into a form we might try to describe as two-dimensional – the caveats about varied thickness and depth still applying to invalidate that name. Suh, perhaps jokingly, says represents ‘his desire “to fit my childhood home in a suitcase”’. The theme is of course about the portability of external representations of memories of spaces into other spaces – all of which may claim to be nameable as ‘home’.

The other joke here is about storage – external and internal and the forms such storage might take and still be a memory of home or a transportable memorial version of home into a present one. That the parts transported are themselves places of transition – passageways and staircases with railings and door openings (and closures) is part of this process of memorialising things that can be seen and things that are transported still to stay shut in.

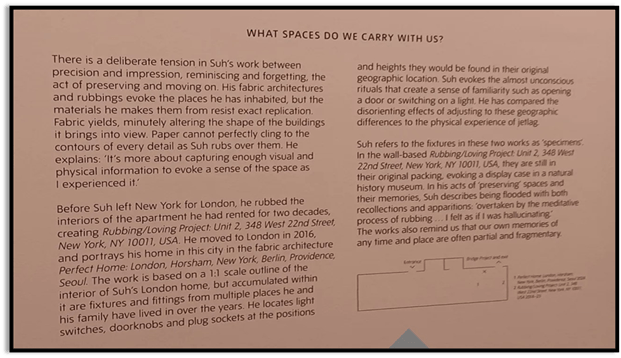

A useful plaque in the exhibition sums some of this up with regard to other pieces – called Rubbing and Loving.

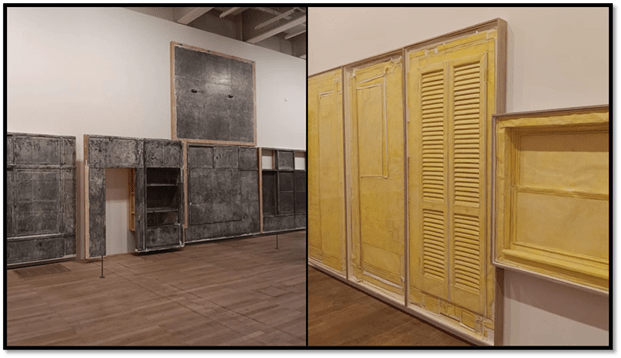

As this statement explains, though not referring to the grimmer piece (below on the right of the collage) called Seoul home – these pieces are deliberately flattened out of their dimensions as they would appear in an interior but have the three-dimensionality of relief sculpture. They represent memories – coloured by predominant associations of homes that have become portable as objects on the outside of the self but representing internal objects – ones manipulated through time, space and transitional events and processes. The artistic process itself – rubbing (a method much used by Marina Abramovic) impels bodily sensation of a different kind into the recreation of this hybrid of past, present and transitional experiences. He equates those sensations with loving – itself a multiple kind of experience and involving some graphite like hardness sometimes.

Left: Rubbing / Loving: Company Housing of the Gwangju Thater 2012, Graphite on paper, wooden structure. Right: Rubbing / Loving Unit 2, 348 West 22nd Street, New York 10011, USA 2014-23. Coloured pencil on paper and stainless steel pins.

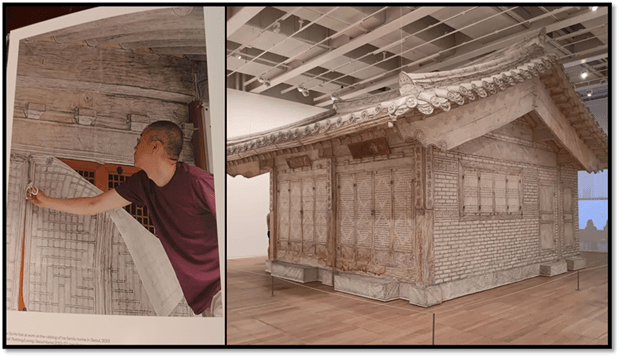

One of the most moving (literally and physically as well as by internal feeling) pieces I saw was Rubbing / Loving Seoul Home(2013-22) – Graphite on paper, aluminium etc. It was made in the USA on 1:1 scale by rubbing (see the artist at work on the left below from a catalogue photograph, so that it was more than a memory of his childhood home, it was a detailed caress of detail with the pain and tedium that also involves. Do Suh talks of the process as ‘a gentle gesture of loving, caring and being attentive’. But that loving is a kind of rubbing (emphasised by the similar sound of L and R in Korean) suggests to me that such intimacy is not always comfortable. [3]

That a home is a space (geographical as well as temporal) as well as a place is obvious, but it is also clear how from this Do Suh arrives at the concept of home as a space that is either a bridge between places or situated on that length and duration of that bridge, not always comfortably, There is much discussion of bridging in the catalogue that I recommend to you. For me some of Do Suh’s childlike pictures suffice, but in doing so they remind me that bridges are a kind of passage and can play the same role as a tunnel and bring us into consideration of the beautiful work known as Nests (the picture from the catalogue is below on the following collage. The bridge goes between Seoul and the USA where two homes of Suh’s were but Nests embeds homes (and the stuff that makes homes inside, outside and a passage between them as transitional spaces along the length and duration of itself. Sarah Fine plays more with the terms ‘bridge’, ‘project’ (with its senses of future plan, objectify and throw outwards all intact) in her essay in the catalogue.[4]

Below are other conceptualisations and realisations of bridges as homes – or as uncomfortable structures sitting on inappropriate foundations, where defence is as important as love – for security is a problematic spatial concept, involving walls, barriers and opacity rather than transparency.

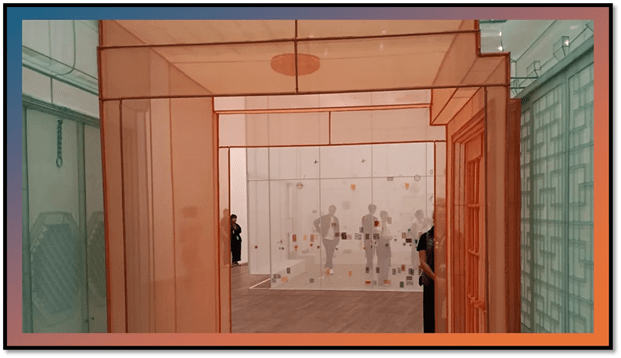

If Nests is obviously about homes and shelters (about ‘nests’ animals make and compound), it also, in this show it bridges the opaque Seoul Home – opaque because you cannot see its inside from the outside – and projects out to the transparent Perfect Home (based on Do Suh’s Horsham home in the Uk but with many memories of earlier homes within it). The picture below shows the portal of Nests from which I exited my walk or passage through it to the visible Perfect Home, with visitors already visible within its mesh.

Nests is my favourite work, I think of those I saw – but only just. Below the collage shows the labelled entrance see standing by the Rubbing / Loving Seoul Home. On the right is it complicated middle section – more opaque than the end passages because doubly housed. It is a conceptually complex work yet delightfully simple to like.

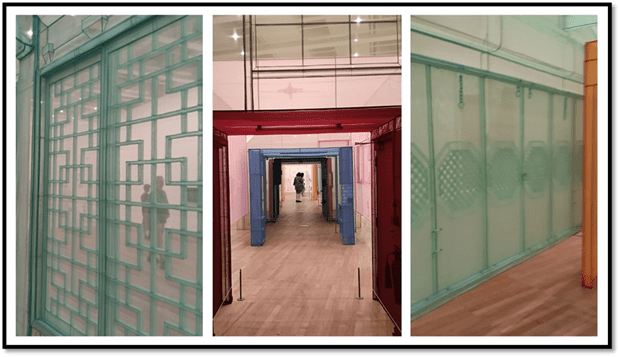

Basically a ‘walk’ through houses and parts of houses that constitutes homes for Doh Suh, it projects outwards to a future but, in its midst lingers on pasts – one’s own in Do Suh’s case but also in cultural histories – even of items that define the ‘domestic’ for different cultures. These show variations in opacity and transitions between public and private access as in the two modes of Japanese walling represented at the wings of the collage below. Colours both queer the experience and regulate moods within it.

The most basic of ‘items that define the “domestic” for different cultures’ in house or home spaces are often means of negotiating from within and without exterior and interior perspectives of the space. Windows allow visual access from the inside out but also frame access visually for those outside to a section of the inside. Hence they matter a lot in Nests, where outside and inside are always and throughout its transit open to negotiation, even through the filtered visual access its walls sometimes give. But even the time-specific inventions do this – like the fifties air-filter below. It feels an object here both familiar and alien – perfectly uncanny then for such a common item (or at least a common item once upon a time). In this way items queer space and time perspectives and make the known take part in the unknown.

Doors, or their frames with doors absent matter even more in the experience of passage through this bridge. Do they offer opening or keep you shut in – whatever, they do so in their own cultural style so the experience of doors in Nests is continually transcultural. Even twentieth-century door types have a kind of temporal periodisation within – even more complicated when they are represented from memory with associations known only to the memorialist.

Some doors are near windows, others have them in them or in their frameworks – all modify the opacity of the access to the outside through the treated linens from which they are made.

Within there are portals between sections but these are complicated by the fact that the transition between sections is sometimes overlaid by complications of superimposed structures or otherwise either a graduated or an abrupt transition- the level of which is often mediated by the ambient colouring and relative opacity of the structure. Even the portal out seems, partially at least from sone angles of vision, blocked by The Perfect Home. We end with Nests then, where we began – its ending being another beginning.

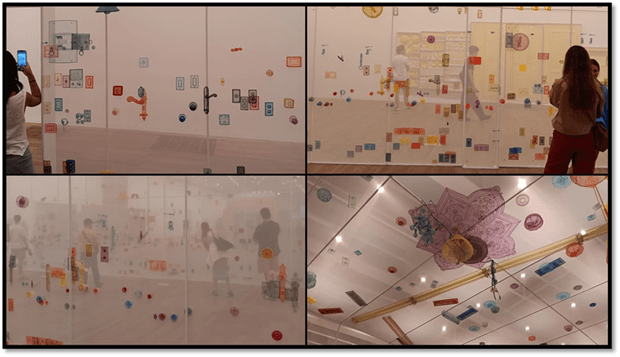

Once inside Perfect Home, however, our sense of interior and exterior is constantly played with – with objects in the home and decorations on its surfaces often taking on a ghostly or apparitional look. We see people inside it, and outside it – some of the latter on the outside of the other side of the home from which you stand – so even visitors or guests to our ‘home’ seem somewhat phantom-like. Objects like doorhandles are divorced from doors (as they might be in inner memorial storage inside me) and so everything is queerly anormative whilst being in itself entirely familiarly ‘normal’. The ceiling decoration has layers from its own history visible – once bearing a ceiling rose now evanescent, for instance. The experience is strange rather than beautiful – in Freud’s sense uncanny or unheimlich (un-home-like) which , according to Freud too the homelike (Heimlich) always is because of its repressed unconscious content.

I actually doubled back into the exhibition hall into a niche where the other candidate for my favourite piece in the exhibition stood, Home Within Home (Scale 1/9) [2025]. This piece is one of many on the same theme (some – in larger exhibition spaces – on 1/1 scale to the houses to which they were memorial. It consists of a large nineteenth century semi-classical house style – based on a real one in Providence, USA, encapsulating a Korean hanok, the type of house of which the Loving/Rubbing Seoul Home is also a representation. But if putting one form of architectural structure within another alienates both sense and proportion the whole structure is radically and visibly split along a median line. Clearly our vision here is radically queered. The conception is similar to those pieces where homes from a distance are seen to be brought into collision (there is an example above) but here the ‘alien’ hanok has been entirely ingested or absorbed – or has it?

The play of green and white colouring also queers our senses, as do the inaccessibility of the size and position of some portals to see inside (open but small doors and windows) or closed ones which block vision entirely. It is a wonderful piece which is about architecture and yet not – about precise measurement and the unmeasurable in our evaluations of the built world.

In another niche of the gallery we find a kind of artwork that is both beautiful and so, at least superficially, unlike that we have seen before. They are the equivalent for Do Suh, he tells us, of drawing for him, which he believes he cannot do. They are based on drawings that are then finished off by the uses of sewn-in coloured thread – some threads connected whilst others hang loose – and sometimes frayed at their ends. As I have before hinted supernatural and / or psychosomatic visions haunt the artist – there is more on this in a fine essay in the catalogue by Sean Anderson.[5] Anderson argues that the role of phantoms and ghosts in Do Suh is to form pictures of how the passage of time and the loss of objects or persons through time, distance of space or other removal like death, is introjected. These pictures are then, in a real sense deeply connected to the other art being about the multiplication of lost selves in the continuing and ongoing ones, searching for some unreal origination. They go about showing that in the most beautiful of ways.

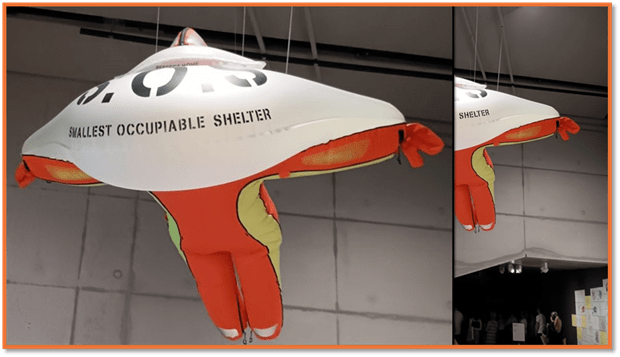

I loved these. Indeed I may have been overwhelmed either by them or the accumulated day for I lost patience in putting myself out thereafter to find out how to like what followed. The inflatable representing the ‘smallest occupiable shelter’ though I like the unrealised project drawing of it in the catalogue felt and still feels too conceptual and narrow a piece to be interesting.

Behind it in a darkened niche a film of the ongoing Bridge Project (1999-ongoing) is shown and the pieces I saw and the stills in the catalogue fascinate me – but the social organisation of seeing it not only irritated but alienated – a bench fit for say six people – was full and the floor covered by younger spectators. I couldn’t take it and literally trudged straight out through the dark exit.

Beyond that however, back at the entrance to the exhibition hall is a treat, a piece the Tate now owns, Public Figures (2025).Actually a highly realistic empty plinth it shows a denial of the usual ‘public figures’ usually lifted on to it. But beneath it are very many small hyper-realistic green figures in the act of bearing up the plinth. As the text on this piece in the catalogue makes clear this piece is about the oppression involved in asking viewers to ‘look upwards’ for public leaders whilst ignoring the fact that this act has to borne by the small figures at the base of society who hold it up – who HAVE to hold it up lest it crush them entirely. All of that is conceptual but it moves you too. Why green? The term for ‘general public’ in Korean is mincho – also meaning ‘public grass’.[6]

That’s all I have to say today but it constitutes a ‘plan for future travel’ as asked for – try and entrain yourself, Stevie, to not do too much on one day away (especially a hot day – for the futures holds too many of the these rather than cool ones, given global warming). Do go and see the exhibition but choose a cooler day and don’t do too much before it as I did. You will be sure to love it – or most of it.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] J.J.C. Smart’s 1955 essay (1967: 165) Spatialising Time in Richard M. Gale (1967) The Philosophy of Time: A Collection of Essays New York, Anchor Books Edition.

[2] Do Ho Suh & Janice Kerbel In conversation (2025: 89f.) in Nabila Abdel Nabi & Dina Akhmadeeva with Arnie Corry The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh: Walk The House London Tate Publishing.

[3] Ibid: 46

[4] Sarah Fine (2025) ‘Bridges, projects and Bridging Projects’ in ibid: 106 – 111.

[5] Sean Anderson (2025) ‘Ghosts’ in ibid: 96 – 101.

[6] Ibid: 58