Okay, lets deal with the elephant in the room first. When we hear the term ‘sustainable lifestyle’, we are perhaps meant first to look at how individuals manipulate the way or ‘style; of how they live to make it more possuible for that life mode to be sustained over time. It is meant to be, we think about how individuals take responsible for scarcities in the economy and the environment – ensuring not only that they can justify their use of resources in the short term but have a plan for their ability to have sufficient resources to keep on living thus, rather than to make drastic changes. Hence it is used most in terms of lifestyle suited to harmonious co-existence with the limits of the income we receive and the environment in which we live without exhausting the benefits of either. We are used to thinking now of dealing with precarity – the thought that things may not continue to be available to us or advantage us unless we take responsible for precarity – the thought that things have a possible end, are finite not infinite, as magical thinking, in many of its forms, pretends them to be.

But we could take the phrase back to brass tacks. Sometimes – for some much of the time – life itself seems precarious: at threat from contingencies of physical accident, health and /or mental distress. Suicide is sometimes a means by which people unable to deal with the constant (to them apparent) precariousness of life situations by ending life themselves – a means of turning the fear of endings into a certainty within one’s own control, rather than that of others. In this context – asking and practicing how to sustain life is even more urgent and a kind of necessity regarding what is substantial, rather than being the style of one’s life.

It may be that we read novels precisely because life would be continually precarious without the models it provides of vicarious survival – sometimes it does it with a moral sledgehammer, as Jane Austen in dealing with the various problems associated with a lifestyle consumed by vanity in Sir Walter Eliot in Persuasion.

Yet her novels can use a sledgehammer with Sir Walter precisely because it is not the precarity of the lives of him, or those like him which matter to Austen, but women whose lives are structured as precarious – and the novels abound with examples of those for whom life has already become hard to sustain for one reason or another, such as Miss Bates – and potentially Jane Fairfax – in Emma, women whose lives are vulnerable if without the means or qualities of being connectable in marriage.

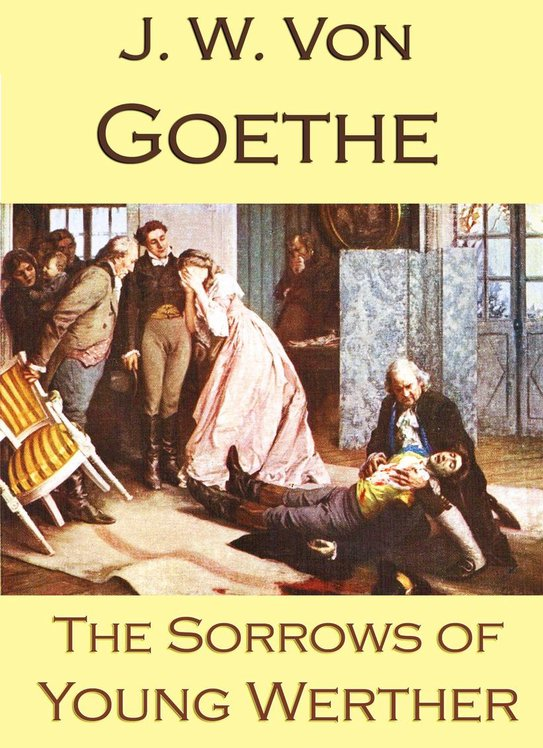

So what of queer young men in twenty-first century England, even ones with some beauty and talent like Isaac in the novel and his author Curtis Garner. Is life precarious? I think some may miss this in the novel if they see it as merely a queer-teen-lit romance, though it is that too, even if they also see that, as in Jane Austen, the aim of a novel as a Bildungsroman is to ensure the scales of magical romantic thinking and narcissism [where one feels both ever lovable and thence necessarily beloved] fall from its hero’s eyes. In this sense, this novel is in the tradition of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, where the scales remain in place and Werther kills himself

Isaac unlike Young Werther survives – at least until he has come through the consequences of a love affair that seemed to him but which threatened his autonomy and even his life, though not by his own direct agency. That he survives is clearly indicated by a capacity gained to stop requiring control of, and certainty about his future and a greater ability to survive in the here and now with energy and ‘eager to get up in the mornings’. With Karim he finds an ability for each to feel good about themselves without any need or question about being ‘certain of any sort of future between them’. [1] Is the issue here that a sustainable life is only possible when sustainability is not the measure of every relationship to others, and the feelings and thoughts that scaffold relationships are allowed to change without being thought to be either permanent in nature nor maintained entirely under one’s own control.

Archie Marks in his review in Redbrick says some useful things that nevertheless need their assumptions unpacking:

The novel would perhaps make for a fitting double-bill with André Aciman’s novel Call Me By Your Name, which similarly uses the vehicle of an age-gap relationship to probe into the horror of self-discovery, of coming of age, and of first love through a queer lens – all filtered through delicate, sensuous writing that maliciously presents itself as romantic (though Garner’s novel, thankfully, makes more of an effort to outwardly portray the central relationship as problematic, especially as Harrison turns abusive). Then again, isn’t the blurring of romance and tragedy the point? Isn’t that something everyone – not just queer people – must endure as we come of age?

That point about writing – I italicise and bold it above – that ‘maliciously presents itself as romantic’ is very good in terms of both novels, for the viability of romantic love as the measure of relationships is certainly to the point in this novel. In yesterdays blog (see it at this link if you wish – but I quote the relevant passage below):

And let’s be honest the issue is in queer novels. I am currently reading Curtis Garner’s Isaac and it is there too in the expectations of a boy growing into his queerness. Most of the novel deals (I haven’t finished it yet and will blog properly when I have) with meeting an older guy, Harrison. When standing down a group of men presenting as macho heteronormative, Isaac thinks that: ‘Harrison wasn’t afraid of anything. he would change the world, …’.

However, this powerful, hard man is not enough. Isaac wants to see, and does, ‘a flicker of his uninhibited kindness and sweetness’. He would be a hard man capable of giving ‘him tenderness’. (*)

From my previous blog: (*) Curtis Garner (2025: 141f.) Isaac Harpenden, Verve Books.

What Marks rightly notices is that the romantic in this passage is entirely ironic – a sign of the young man’s (he is seventeen) immaturity and the psychological baggage he carries with him, especially the need to relate to older men as sexual objects and simultaneously the basis of authority in his life – fathers to replace the one absent (his biological father) or, as Isaac feels him to be, inadequate (in the form of his step-father, the rather nice Leon). That Harrison is older elevates him not only to the object of romantically sexual love but to an authority: whose word alone justifies Isaac modelling himself on Harrison, even down to choice of books (ironically, one is Nabokov’s Lolita – also about the interaction of age difference and sexual desire under the shadow of abuse of power). That Harrison alone is not to ‘blame’ though for maintaining the power dynamic between them is emphasised by a parallel relationship Isaac has with his teacher, familiarly called Ben) – and who is tested by Isaac with an indirect proposal – in an unanswered email – in the form of a confession of his feelings, a desire for sexual congress in the form of a recognition of Ben’s authority and efficacy as a teacher. The sexualisation of Ben occurs in the prose of the narration itself, which appears to attribute a kind of consciousness in Ben of his own allure – emphasised by, though what is seen below is apparently from the point of view of Ben, he is apparently not even looking at Ben’s hands roving over the area of his groin but at the doodles he creates in his exercise book:

Ben sat against his desk and faced the class, the fabric of his grey trousers stretching tight across his thighs like curved slate. He’d occasionally run his hands over them during the next forty minutes as he spoke about the nineteenth century while Isaac joined up the lines in his notebook …. [2]

When he tells Harrison about liking older men in particular, including the ways he performed to their supposed preferences, Harrison sarcastically asks him: “Don’t have a daddy complex, do you?”. Later, when Isaac confesses (he is always confessing as if to a priestly authority) that when he had been with ‘older guys’ he had imagined they’d been him’, Harrison cruelly interprets the Daddy complex as obviously Oedipal, ignoring the muddle in Isaac’s head: “Sounds a bit Freudian”.[3] Yet no-one links this to the protagonist’s name : Isaac, prototypically the son in the Old Testament of Abraham and a sacrificial lamb in potential to test his father’s God-given authority.

‘Isaac’ is the single word name of the protagonist and of the novel itself. The opening of the novel not only emphasises this but shows that the protagonist is his own most critical reader, although apparently, we will learn only of his profile on Grindr, a queer dating app: ‘The more he read his own name, which was all his profile specified, the more he feared it lacked consequence’.[4] The desire for consequence feels to be to be central to the novel and how we read it. This boy needs a role in his own right, as Isaac has in the Old Testament differently interpreted in the Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions – becoming the icon of the father of Israel, and himself beloved of God. If anything the novel proves that the problem for Isaac is this very hope of predicted elevation and significance, and of achieving it, before he learns better, from the people he gives himself to as a confirmed ‘bottom’ (or so he thinks) and from the authority of some ‘top’ positioned above him:

“Are you top or bottom?” Luca asked, moving Isaac’s hand to his crotch. He grew and throbbed beneath his jeans.

“Bottom,” Isaac said, unable to remember when he’d decided he was born to take instead of give. “Can we have the light off?” [5]

Strangely, because bottoms ‘take’ rather than ‘give’ the phallus as the symbolic of masculinity unrelieved by any non-binary qualities, this issue is also reminiscent of the complex nuance with which Isaac continually negotiates his sex/gender identity: hating to be feminized but rejecting the ‘hard’ formulations of the masculine available to him except as forms imposed on him from without in another forceful masculine type. Isaac never quite with the novel really sorts out his issues that he confronts in the episode with Nick, whose sexual identity involves cross-dressing, to Isaac’s disgust (and for which he is taken to task by Harrison) but which rhyme with his own childhood enjoyment of his mother’s clothing: ‘the silkiness of her dressing-gown and pyjamas, which embodied the softness of her’. [6] That clothes ’embody’ is not a lesson effectively learnt in this novel, but like much else it lives under its surface. In the end the novel sticks with its need to determine how Isaac might find a powerful active purpose – the ability to give as well as take in every sense of the word.

For binaries entrap and this novel is above all one resistant to an entrapment that it yet finds a common in life, even non-human life. It is difficult to forget once you have fully taken in a scene in Isaac’s friend, Cherish’s, flat though it is not symbolic of much in the external scene but is of a lot in the half-realised psychodrama of Isaac’s attempt to find a significant space in which he has autonomy:

A yellow glue trap hanging near the window shivered as a plane flew over the flats, prompting a trapped blue bottle to try and buzz itself free. [7]

Existential or other freedoms are not for all, least of all blue-bottles, but it helps to know that you can kick against the pricks by becoming aware of why you feel trapped, opening up even to the fact that the magical thinking of romantic love is one of those things. That fly reminded me of Isaac’s earlier dreams as he flies back from his fated holiday with Harrison, still unaware what it meant when Harrison hit him hard as they discussed time apart about to happen, but hears of a weather-based delay which sticks the plane they are travelling on to a foreign airport’s ‘tarmac’:

Many of Isaac’s stories began with a similar premise: two people in love, trapped in a space with each other against their will. [8]

This is the dilemma of the novel. Isaac’s apparent romantic needs are for a patriarch (a real; or substitutive father) to authorise his stories as authentic and worthwhile, whilst holding him in certain embrace forever. Hence despite these images of traps much of the fear he does acknowledge is the fear of change – moving, losing people and not feeling ‘wanted’. The crux of the novel’s handling of this dilemma is being told, as he interprets it, that he had as an infant been put in care by his mother and therefore must not have been WANTED. It takes his mother to tell him that: It was never about not wanting you, Isaac’. From hence he learns that his mother, though his symbol of soft caring that is permanent or is nothing, has her own vulnerabilities – to the point of attempted suicide – and knows loving is practical and difficult (even to the point of not knowing how to part Isaac from his constant need of comfort blankets like the coat he refused to be parted from as a child.[9] Although she loses the men she gives herself to, like Leon, in the end she understands their vulnerabilities (though not standing for their perpetuation in her own life) and that for Isaac an inadequate but well-meaning father like Leon is better than none at all.

Isaac thinks in terms of either romantic wish fulfillment, where nothing is allowed to change, or tragedy as the meaning of change. Early in the novel he contemplates’s his pick up’ Luca’s landlord Pete (‘paternal and childlike’) , scratching together a living from the remnants of his earlier losses. Hearing this story of change in the real circumstances of the world in which Pete demonstrates his resilience and humour he hates the thought of a life of brief queer encounters that he reads of in Dancer from the Dance (see my take on this book at this link) that he thinks lies ahead as a symbol of ‘divorce’ (as parting), loneliness and relentless unfulfilled ageing:

His chest felt as if it were being hollowed out. He thought about Pete with his house in Greenwich and his dog. Divorce. Growing old. … [10]

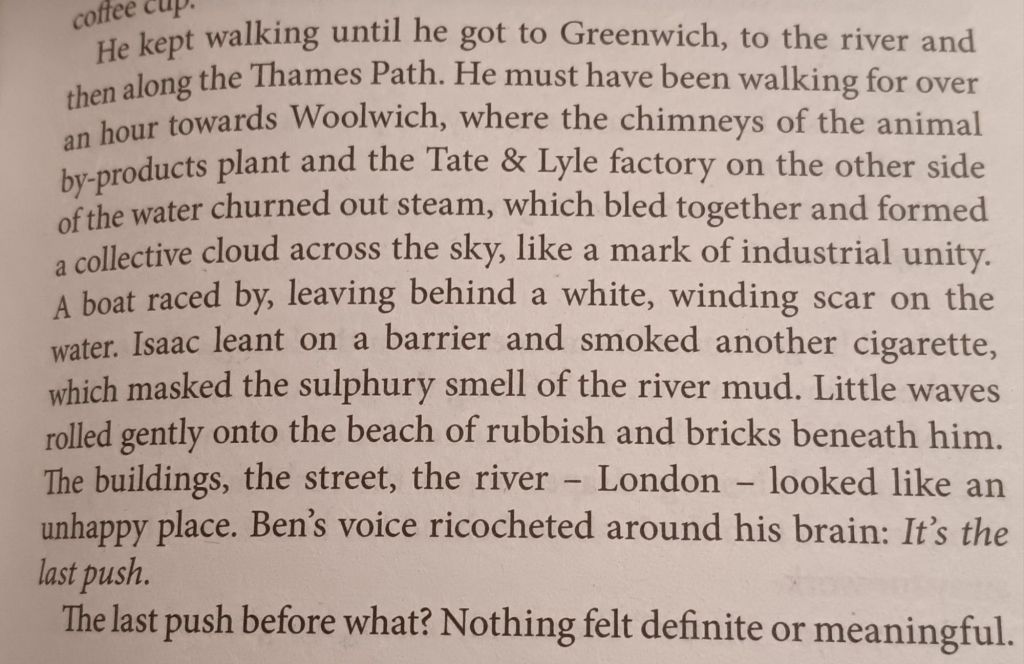

But uncertain futures are not the hell he imagines them to be , neither is having a nuanced view of our need for romance and an understanding of its pathology, which his mother has in buckets, knowing that, for Leon, making ‘romantic gestures’ after he slept with someone else but her was necessary for him and understandable but that it sickened her. [11] Had he read the books he loves so much – he would know this to a certainty – Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair (he recommends it to Harrison’s friend), Colm Toibin’s The Blackwater Lightship and even his A’level text Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge. All of these texts pivot on the acceptance of uncertainty and not holding on to what MUST fade (even Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray mentioned early in the book). One of my favourite phrases in the book is related to Isaac’s attempt to learn from his teacher Ben following their last lesson. As with other men he feels he has ‘lost’ Ben and feels in a ‘strange purgatorial state’. My favourite phrase follows an incredible passage of writing conjuring out of East London purgatorial, perhaps even with a hint of Dantesque infernal, sense of catastrophic and apocalyptic gloom out of that phrase:

Curtis Garner Isaac (2025: 57) Harpenden, Verve Books

The ‘last push’ is clearly a crucial concept in the notion of the bildungsroman even if never, to my knowledge at least, used before. Whatever Isaac’s confusion here about what Ben might have meant by it – and some of the meanings are clearly wishful or magical thinking about being taken sexually by his romance hero – Ben’s probable meaning must have been crystal clear. As school approaches its end, pupils will need that last energetic push to launch their futures. But Ben thinks about this term in the context of a waste land akin to T.S. Eliot’s. any effort leads to a future dominated by a ‘collective cloud’ of ‘industrial unity’, where manufactured sweetness ‘bleeds’ into the killing of exploited lives – animal or otherwise. Dominated by experience that hurts or scars the future is ‘an unhappy place’. The ‘purgatorial’ context may in part explain the way in which industrial effluent is best described in ‘sulphury mud’. My own bet is that all of this association is a product of the fact that passage is from the point of view of Isaac himself,. left behind in the purpose of God the Father (or Abraham). The future may lie behind the ‘last push’ but that the future is indefinite or less than meaningful is totally unsatisfactory to Isaac, and that to an extent is a problem for us all : ‘The last push before what? Nothing felt definite or meaningful’.

The irony is that the turning point of the novel itself concerns a ‘last push’: the push Harrison gives to Isaac’s back to send him falling down the stairs and to serious injuries. [12] I try to restrain myself from equating the fall down stairs with the fall that followed God’s last push of Lucifer from Heaven to Hell. The fall down the stairs, which in enforcing time out, allows not a different future for Isaac to emerge, though with more serious injuries that may have been possible – for anything is – but a different attitude to the future in Isaac, one that does not expect or need the definite or a prescribed meaning. At the end of the novel, Isaac is accustomed to falling and embraces it as he embraces uncertainty rather than the expectations of magical thinking, especially of romantic magical thinking. Note Isaac’s reaction to being ifted a notebook for his writing by the gorgeously lanky Karim:

It was like missing a step and not knowing whether he would touch solid ground again. The fall would go on and on, and he couldn’t decide whether he wanted to lose himself in it.

Consider all the synonymous phrases here for uncertainty in knowing – missing steps (in logic) for instance. Isaac reminds me of the problematic hero of Tennyson’s Maud, except where the latter refuses not to know what he wants to know but can’t and sees not knowing and falling as failure, Isaac is beginning at his, like his mother to appreciate the advantage over magical thinking of expectations and the romantic.

1.

O let the solid ground

Not fail beneath my feet

Before my life has found

What some have found so sweet;

Then let come what come may,

What matter if I go mad,

I shall have had my day.

2.

Let the sweet heavens endure,

Not close and darken above me

Before I am quite quite sure

That there is one to love me;

Then let come what come may

To a life that has been so sad,

I shall have had my day.

And even before Isaac learns the need to embrace UNCERTAINTY against the expectations of ROMANCE with Karim, he was beginning to see that perhaps desire, in reality, depended on a kind of unknowing of the other tjhat made power imbalances important to make passion thrive and not die. Read the exchange yourself and see where it fits into the construction of Isaac’s maturity. [13]

One could say more – there are many felicities in the novel that raise puzzles, like Harrison’s choice of a date in a cemetery for his first meeting with Isaac, the interplay of discourses of art – especially dramatic art – and the ideas of love, the unending puzzle about the nature of sex/gender and the puzzle that irresolution always poses when it is the conclusion a novel reaches.

Do read this novel?

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_________________________________________

[1] Curtis Garner Isaac (2025: 281) Harpenden, Verve Books

[2] ibid: 10

[3] ibid: 77 & 105 respectively

[4] ibid: 7

[5] ibid: 21

[6] ibid: 52

[7] ibid: 126

[8] ibid: 59

[9] ibid: 152, 228 – 230

[10] ibid: 31

[11] ibid: 132

[12] see ibid: 238, 241.

[13] see ibid: 166f.