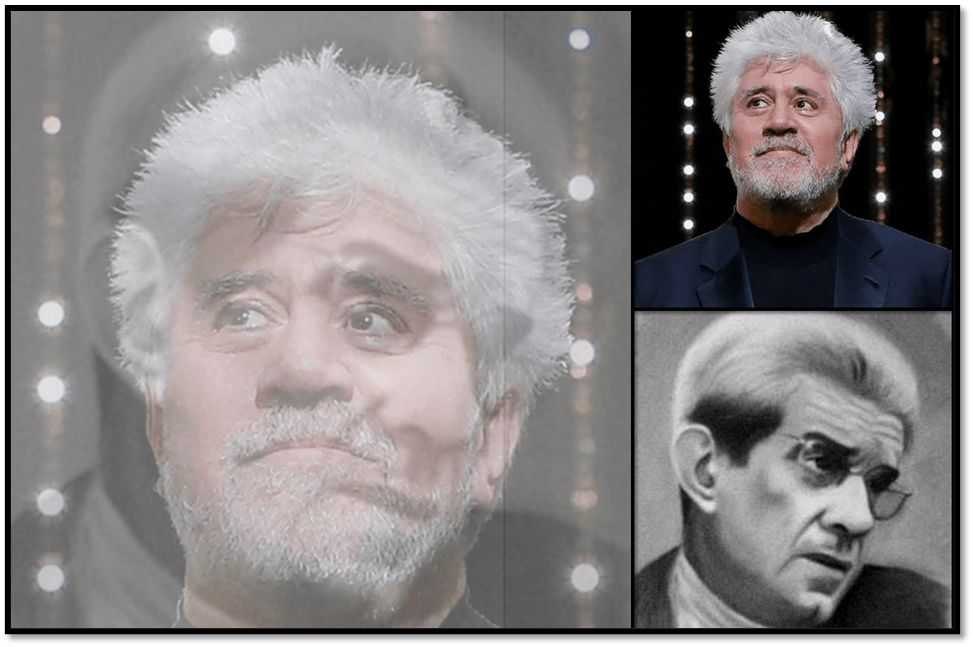

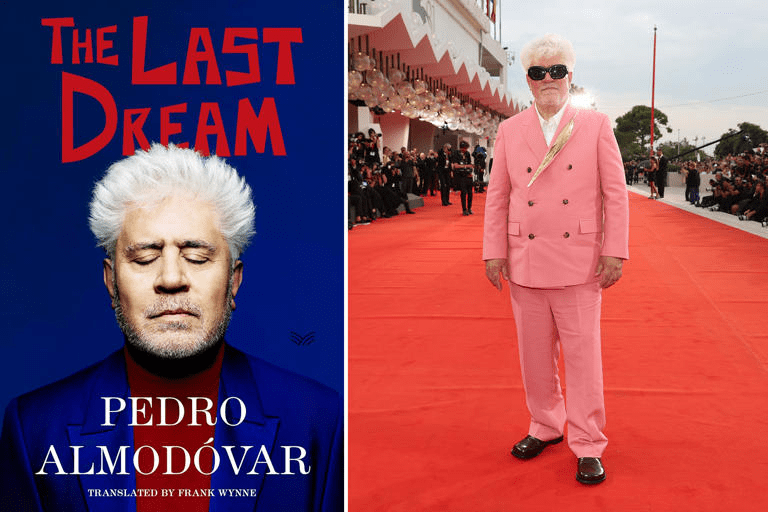

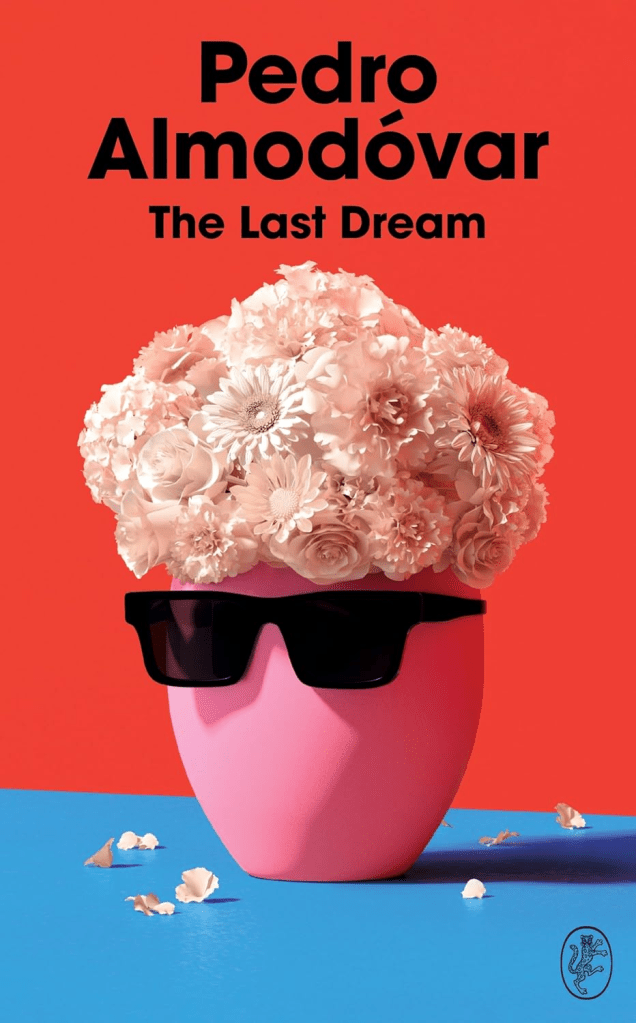

Let’s say my favourite ‘historical character’ is a mixture Pedro Almodóvar and Jacques Lacan, who are both ambivalent about mirrors. This blog reflects on stories in Pedro Almodóvar (2025) The Last Dream (translated by Frank Wynne) Harvill Secker London (Penguin, Random House).

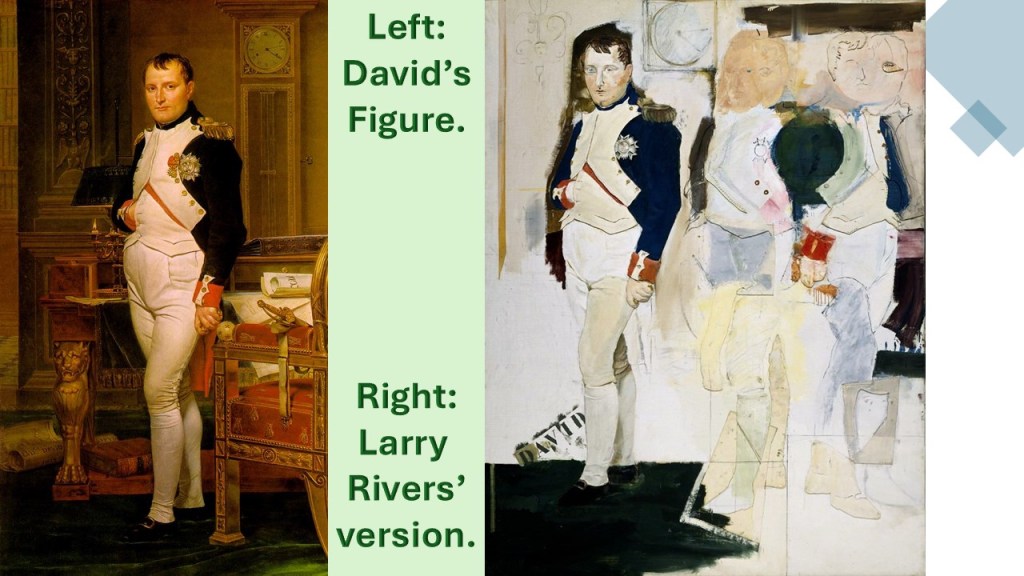

This blog has to be a bit circumspect about the concept of the ‘historical figure’ and the notion of favourite. Historical figures are difficult to dissociate from the confabulation that constructs them, however much diverse contemporary and autobiographical accounts (in the end fables too) are taken into account. We desire to see our figures whole – embodied in some image. It is one reason Larry Rivers gave us ironic distance from David’s Napoleon – to suggest that no figure can be seen whole or in one iconic form only, without some form of desire being involved in its construction:

Historical figures that we favour are usually favoured, I assert, because they are an image in a huge reflecting mirror that returns to us the form in which we desire to see in ourselves, however that desire is framed (in terms of sex, love or politics). In that respect the act of nominating a figure models, in the psychoanalytic thought of Jacques Lacan the means by which children learn to form a whole and unitary image of themselves, even though that image does not reflect how the person seeing it experiences themselves operating in the world.

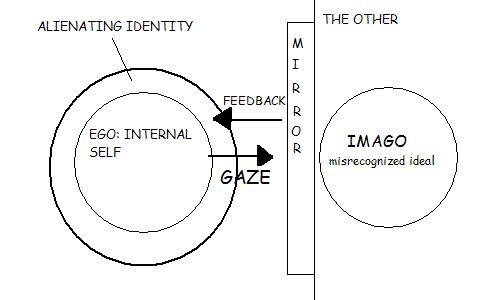

Here is a simple explanation of the mirror stage from the web that doesn’t pretend to be comprehensive but at least sheds light:

Lacan argued that the mirror stage marks the beginning of the individual’s sense of self or “I.” However, this sense of self is not entirely real—it is based on an external image and involves a process of misrecognition. The image in the mirror is idealized and whole, while the infant’s actual experience is more chaotic and incomplete. This disconnect leads to the formation of an identity that is shaped, in part, by something external, setting the foundation for how individuals relate to themselves and others.

For Lacan, the mirror stage is a formative experience that influences a person’s subjectivity and relations for the rest of their life. It signifies the start of a lifelong dynamic between the internal self and external perceptions, a process central to his psychoanalytic theories.

This example helps to clarify this philosophical perspective. Consider a young child standing in front of a mirror for the first time. Initially, the child may not recognize their own reflection; however, as they watch, they begin to connect the movements in the mirror with their own body. This reflection represents a complete, whole image of themselves, which contrasts with the fragmented experiences the child has of their body in reality. The child starts to form an understanding of themselves as a unified individual, an “I.” This realization can be both empowering and perplexing, as the image in the mirror is both the child yet not entirely them. It is through this interaction with the reflection that a new layer of self-awareness and identity is born. This moment is significant in understanding the formation of human perception and the complexity of identity.

(https://philosophiesoflife.org/the-mirror-stage-and-jacques-lacans-philosophy/)

As this piece argues, Lacan called the process of developing an ego image one of ‘méconnaissance’ (which the passage above calls misrecognition – the term used in early translations). The psychodynamically knowledgeable translator Alan Sheridan keeps the original French term in his translations of Lacan into English because there is no simple English equivalent: what is suggested is “failure to recognize”, or “misconstruction”, although this does not apply a false self because there is, in Lacan’s view, no connaissance (knowing or true construction of a concept) without a simultaneous act of ‘méconnaissance’ [mis-knowing’].The process of developing that image occurs in what Lacan calls the ‘mirror stage’, although it is a continuing process and the mirror images it provides is quite complexly structured in the mind of the knower. Thus another explanation of mirror-stage develops some of its complexity:

Mirror Stage and Identification – The mirror stage is defined as an identification, a transformation where the subject assumes an image, shaping the ego’s structure. This transformation is driven by the child’s jubilant reaction to their specular image: “The mirror stage… situates the agency of the ego… in a fictional direction”.

Ideal-I and Symbolism – Lacan introduces the concept of the Ideal-I, the source of future identifications, and notes that this stage of development links the formation of the ego with external objects and social influences. “This form would have to be called the Ideal-I”.

Alienation and Fragmentation – Lacan discusses how the Gestalt (the mirrored image) symbolizes the mental permanence of the “I”, yet is always alienating. The unified image conflicts with the fragmented and disjointed sensations the child experiences: “This Gestalt… symbolizes the mental permanence of the I, at the same time as it prefigures its alienating destination”.

Whereas the child learns to speak about itself as ‘I’ ‘as if that ‘I’ were a whole and unitary object, it has an internal structure made up of parts – some of which parts contradict certain others. This is so especially of the ‘Ideal-I’ which is both an aspiration of the ego and the source of a guilt-inducing critique of the ego. As thin as that explanation is, it does help us to see what Pedro Almodóvar might be up to in his collection of fragments – short stories that are in part the ideas that got turned into film scripts, pieces of autobiographical reflection or fantasies about how different beings construct themselves across boundaries of sex / gender, sexuality, class and power as well as in terms of the real and ideal. Almodóvar calls them ‘texts of initiation (a stage not yet finished)’ saying too ‘many were born of a desire to escape boredom’. [1]

My main aim is to show how mirrors work in some of these fables, especially that fine vampire story: ‘The Mirror Ceremony’. It is an idea though that he uses to discuss his own take on certain ‘historical figures’ that ought to have been ideal versions of his own ‘I’ (as he contemplates writing a diary as Warhol did) but are not – Andy Warhol, for instance, never engages with his own diary as its reader or writer – records things on it – by dictation to an amanuensis on the telephone – but never reflects on himself in the process of the writing’s construction. Here is how Pedro Almodóvar puts it:

If you decide to keep a record of your life, including the minute details, I think the pleasure lies in personally collating them and putting them into words. To me, that’s the game of reflecting or being reflected on the page as though it were a mirror. [2]

Without naming the word ‘desire’ that is the process of construction going on for Pedro, a game in which the pay-off is a pleasing self-image, but as he says in the Introduction, there is very little about himself, as shown in these stories, which are he says, a ‘fragmentary autobiography, incomplete and a little cryptic’. This is not only so in the stories in which he appears as himself ‘without any degree of distance’ but in those of which, though they may have different names and sex/gender or class boundaries (like Patty Diphusa, the ‘sex symbol’ in one story) ‘we are are aspects of a single person’. [4] Sometimes the person is already present in a dual form – as in the character who forms the focus of the great film Bad Education Paula / Luis in The Visit, a trans woman seeking revenge on those who created the bifurcated image of non-binary desire (for neither self nor other) in her and of her whilst damning its consequences in public life, in their everyday selves. At other times the characters are mixed up in in a dynamic of desire that both joins and separates them (makes them alike while different, such as Barabbas and Jesus Christ – and their prison warder – in Redemption or the vampire Count seeking ‘spiritual’ refuge (to drink the blood of a greater idea – that promised in the Holy Mass) and the rector of the chosen monastery for that refuge, Brother Benito in The Mirror Ceremony.

In the latter tale a mirror is used in the initiation ceremony that forms the rite of passage from man to vampire. The portal to eternal life (given the evasion of wooden stakes thereafter – unless you desire one) is first to admire one’s own beauty in a mirror before seduction by the vampire (a male) which renders him invisible thereafter in any mirror thence encountered, suffering ‘the pain of being unable to see oneself’, ensuring the ‘opacity of mirrors and all reflecting surfaces that depend on light’. The ceremony itself involves the theft of a ‘large mirror’ by the Count in the form of a bat, such that witnesses claim to have seen such a mirror ‘flying through the sky’.

Once the mirror is obtained Brother Benito, ‘nervous as a bride’, strips slowly in front of it on the Count’s command, seeing himself naked for the first time ‘since he was a boy’. It evokes an ‘unexpected nostalgia’ that renders him expressive of self-desire – stroking ‘his legs, his chest,. his penis …’, and finding in himself a fit object of desire: ‘more handsome than he could have imagined’. This moment of méconnaissance is experienced to the end as his body – the only one visible in the mirror as the Count ’embraces him’, such when his ‘arms wrap around the vampire’s chest’ he sees only himself arching ‘his back in a gesture of rapture’. until they reach a point of literally drained exhaustion ‘sprawled on top of one other (sic.),.as if they had just made passionate love’.

The odd thing is that attainment of queer desire is the moment at which both become opaque in the mirror, as if méconnaissance in the apprehension of self were no longer a feature of the lives of those lives as, in the form of bats ‘they flutter from the chapel and lose themselves in the dark of a night that now holds no mysteries’. [5] If the only way queer men find themselves is losing themselves in the dark night, then knowledge stripped of mirror images that fake the self is like shedding at last heteronormativity, and the whole symbolic order it represents and sustains – of class hierarchies and so on. This is not, unlike, the state of freedom from God achieved by Jesus Christ and Barabbas in Redemption. The prison warder says of Barabbas, when he enters the cell the morning after he, though the ‘utter darkness’ still perceives ‘the outline of their bodies, panting and shuddering, on the same bed’, that:

In the presence of the stranger, this most brutal and fearsome rogue no longer recognised himself, concerned as he was for someone other than himself. [6]

Clearly the mirror stage has, for them been passed through, though what lies within the dark cannot be recognized by those of us still tied to the world of mirrors (and the blend of fact and fiction in méconnaissance). It is not a passage experienced in the story Too Many Gender Swaps.In that story the narrator, a cult-director like Almodóvar, finds his art serving his partner’s greed for images of himself he favours. The one thing he won’t or cant play is a character who ‘gets involved in other people’s problems and through them he finds salvation’. [7] For the other is behind the mirror, not reflected from it.

Too easily the ‘Other’ is a misrecognized ideal, the Buonaparte of David, of the thing that is collected from the mirror’s surface and introjected -the alienating identity of David as imperial servant, not questing artist. Larry Rivers so wanted to find others in that space – multiple and telling their own story.

That is why my ‘favourite figure’ is a means of understanding otherness through stories, for when we choose a favourite figure (a Trump or even a Keir Starmer) we lock ourselves into a misrecognition that might be inescapable until we abandon the mirror as our ideal medium for knowing.

Bye

All my love, Steven xxxxxxx

_________________________________________

[1] Pedro Almodóvar (2025: xiii) ‘Introduction’ in Pedro Almodóvar The Last Dream (translated by Frank Wynne) Harvill Secker London (Penguin, Random House): xi – xvii

[2] Pedro Almodóvar (2025: 194) ‘Memory of an Empty Day‘ in ibid: 191 – 202.

[3] Pedro Almodóvar (2025: xi) ‘Introduction’ op.cit

[4] ibid: xiv

[5] Pedro Almodóvar (2025: 66-68) ‘The Mirror Ceremony’ in Pedro Almodóvar The Last Dream op.cit: 47 – 68

[6] Pedro Almodóvar (2025: 181) ‘Redemption’ in Pedro Almodóvar The Last Dream op.cit: 171 – 189.

[7] Pedro Almodóvar (2025: 35) ‘Too Many Gender Swaps’ in Pedro Almodóvar The Last Dream op.cit: 27 – 45.