‘… uniforms did not just shape and display a disciplined male body but also guided and excited the gazing eye in particular ways’.[1] This is a blog about the role of the uniform in the construction of the object of queer desire in the contexts of the militarisation of social, political and psychosexual cultures based on reading Jeffrey Schneider (2023) Uniform Fantasies: Soldiers, Sex, and Queer Emancipation in Imperial Germany Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

Georg Krickel & Gustav Langeü ‘Das Deutsche Reichsheer in seiner neuesten Bekleidung und Ausrüstung’ Published by Max Hochsprung, Berlin, 1900

On May 2nd 2025 I blogged about an article (in Gay & Lesbian Review – see the blog at this link) on South American art relating to queer desire and the uniformed armed services by Joseph Shaikewitz. Here is an excerpt:

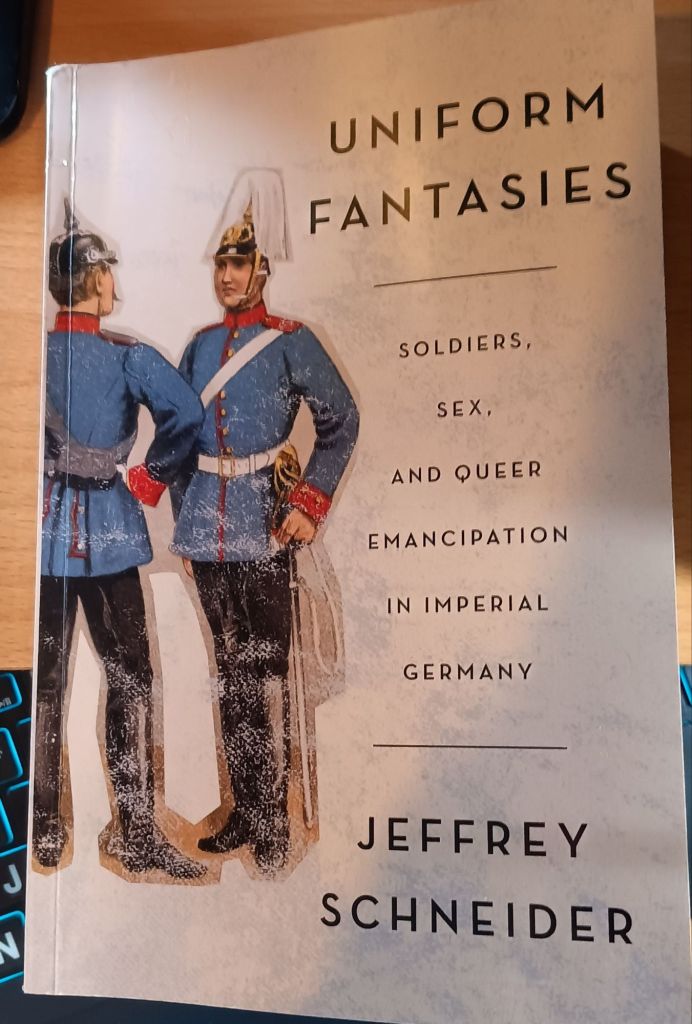

Let’s take Shaikewitz’s treatment of Argentinian artist, Jorge Larco, whose work seems particularly interesting as a vehicle of meanings that have circulated around the definition of male queer sexuality in the twentieth century. Shaikewitz chooses him because his focus, and possibly that of his PhD., is the role of uniforms in the expression and performance of queer sexualities. However, I don’t intend to address uniforms, except where necessary as part of the content of specific paintings, here for I have decided to order one of the books the essayist recommends, Jeffrey Schneider’s Uniform Fantasies: Soldiers, Sex, and Queer Emancipation in Imperial Germany … and will think about the issue of uniforms thereafter with intent to blog.

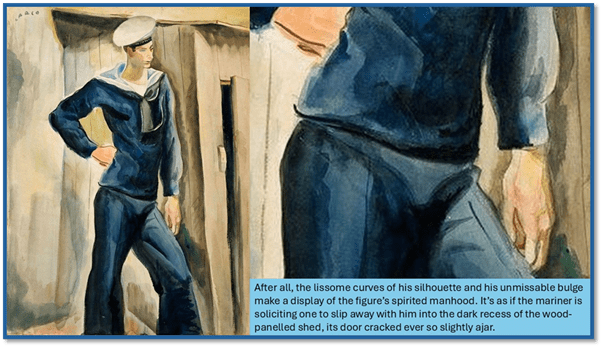

Instead I became interested in the meaning of queer art history and queer art criticism – how it signals, for instance, the evidence that makes it differ from academic art history of the ordinary kind, even where it is not (as most of it is) doggedly heteronormative. Hence i wanted to look at HOW the writer ‘reads’ the art of Jorge Larco, not only as art but as queer art with perhaps a different training of the eye behind it for the iconography and other coded languages of visual art. Let’s take, what he has to say about the painting Marinero (1939). I cite Shaikewitz in the collage below, but not the part that triggered my interest in the kind of licence that queer viewers might take in interpreting this picture. For instance, he ”notices’ with respect of the sailor in the picture ‘his lascivious gaze fixed somewhere beyond the frame’. I just don’t see the painting thus – I cannot ‘see’ what in the gaze of the sailor is ‘lascivious’, nor even that its object is necessarily ‘beyond the frame’. What in there characterises the gaze as ‘lascivious’ other than some projected interpretation of his pose, stance and the suggestive, almost fashioned, dishabille of his clothing, especially that open collar. The arm gesture seems that of the teapot pose that has characterised queer men in art from the eighteenth century, but the eyes themselves could just as much, from what we see, actually show the absence of either focus or motive in the sailor’s eyes, as if he has taken up his pose in a mood of pure boredom at the exigencies of his life – often involving selling sex for money in the period, rather than looking to satisfy his own desire. The citation in the collage seems nearer the point. Here it is again with it explanatory prefatory phrasing:

… the seaman – or rather the idea of him – might have elicited a sense of sexual intrigue. After all, the lissome curves of his silhouette and his unmissable bulge make a display of the figure’s spirited manhood. It’s as if the mariner is soliciting one to slip away with him into the dark recess of the wood-panelled shed, its door cracked ever so slightly ajar.

By the time the writer gets here he seems to admit that his use of the adjective ‘lascivious’ earlier is only a possible reading, as he peddles back from stating the intentions of the artist with regard of exactly how to read the mariner – his look and purpose. Suddenly Shaikewitz is searching to justify his overall sense of the sailor as a picture of ‘sexual intrigue’, invoking the man’s limbs and how he performs their exhibition to a viewer, taking time to concentrate on the unmissable bulge, which I have enlarged as a detail in my collage.

The trouble with Shaikewitz’s reading is that, though it can not be denied as a potential narrative version of what we see, it is also not the only narrative reading possible. There is no doubt that the mariner makes himself available for sexual pick up, but there is no means by which we can know his motive, which could, for instance, be that of prostitution, in which he adopts his pose as a means of advertising. But the reason for that weakness is that it is not essentially about queer art but queer behaviours that might or might not be being revealed.[2]

It is important to restate the argument because I promised there to return to the question of queer desire and the subject of armed services uniforms once I had read Jeffrey Schneider’s Uniform Fantasies: Soldiers, Sex, and Queer Emancipation in Imperial Germany. I have now read that fascinating book and this blog takes on the subject in the light of Schneider’s brilliant analysis of the interaction of queer desire, representations of sex/gender and sexuality in the light of a politics where discourses of the role of the military has become an issue across the social, political (including the sexual political) spectrum of society, as was the case in Imperial Germany prior to World War One and may be the case in Europe and Brexit Britain now, as we speak. Schneider’s book is a very different contribution to Shaikewitz’s article.

It is a totally serious academic work performing to the highest degree the contract with truth as seen by academia – it has a rich and strong set of references that argue its case across many contexts – the establishment of fact as well as the role of fantasy / ideology in the constitution of framing of ‘fact’, and a full consideration of its own methodologies both as history and literary commentary, as well as showing the best way of showing how the disciplines of literary reading and historiography can be combined. Look here then for wisdom about the strengths of different contributions to history generally and queer theoretical history in particular, without any partisanship and much cognitive flexibility that remains nevertheless true to its sources. Foucault is honoured but the limitations of his approach admitted, with returns to the brilliance of Marx where useful (on commodity fetishism for instance and its relation to the construction of pathologies of fetishism, and redemptions of them in which diversities in the aetiology of pleasure are opened up) whilst constantly updating queer theory as derived from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, to include, amongst others, Slavoj Žižeck, ‘rarely thought of as a queer theorist’ as Schneider says, and that latter theorist’s exemplary use of the work of Jacques Lacan. No theoretical contribution is either ignored and none is free of appropriate evaluation as for its fitness to purpose in understanding how and why a knowledge of uniforms contributes to understanding the dynamics of queer desire and the objectification of that desire nor military history and the relationship of ‘militarism’ to the development of statecraft into the history of twentieth-century Europe and especially with regard to a united Imperial Germany (under Prussian hegemony) and its transition to Fascism at the end of the story told .

As a result every kind of discourse about men in the uniform of the armed services is considered, whether they be discourses of critical analysis from our own times or those used in debates about the meaning of uniforms and their features in formal debates, such as in the Reichstag or other legislative fora, the lawcourts in issues of libel, sexology, psychoanalysis, or the confessionals of eccentric pedagogues validated by their currency as advisers about what it is good for boys to learn, including the drawings of Georg Krickel & Gustav Langeü, exampled at the head of this blog, and in Schneider’s book (with different Krickel examples). My favourite example of a pedagogue, which also shows that Germ has a neologism for every possible branch of knowledge or meta-knowledge, says his acquired ‘knowledge of uniforms’ (in his own German as given by Schneider Uniformkenntnis) was so huge it covered examples from across the militarised globe as then known.[3]

How many discourses about uniforms, desire and its political aura does that include? Let’s suggest but a few:

- First, the debate about the construction of the desire and romance of uniforms as an expression of either nation or the nation we desire.

- In some forms on the right this includes a political fetishization of not only uniforms but the norms of aspirational masculinity it represented that could fuel German national cult revivalism. It also fuelled less celebrated social congregations of participations of male-on-male sex and was romantic only in its extreme nationalism. This fuelled the pedagogic enterprise and perhaps elements of early Fascism, such as the cult of the Brownshirts before the Knight of the long Knives. Born of a hierarchical and graded desire familiar in the aristocratic court of Bavaria, it took populist forms later. This is the kind of paradigm of the masculine nation Schneider studies in his wonderful chapter on Thomas Mann’s self-proclaimed ‘homosexual novel’, Die Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull: Der Memoiren erster Teil (The Confessions of Felix Krull: Confidence Man), which he extends to speak of as a debate between himself – a supporter of Imperial German warfare with his liberal leaning anti-militarist brother Heinrich.

- In other forms (if we stay with the less than ‘factual but useful binary) that very fetishised militarism is seen as something not only politically corrupt but also negatively set against the current of progressive history. This feeling fuelled the paradigms of left thinking that were at least marginally homophobia- equating antagonism to the heteronormative as a kind of resistance movement to progress. Schneider controversially instances Adorno here. However, in another wonderful companion chapter to the last mentioned he refers this thinking to Heinrich Mann’s novel, Der Untertan (The Loyal Subject), which he extends to speak of as a debate between himself – a critic of Imperial German warfare with his prevaricating militarist brother Thomas.

- Secondly, the manner in which debate about uniform bifurcated between the sexological Urning movement (and the various sub-categories it represented) who posited a category of the ‘homosexual’ defined by its intrinsic ‘femininity across a range of behaviours, beliefs and actions’ including the need for a Dioning to love (in brief feminized ‘homosexual’ men look for male ‘heterosexual’ objects of desire. The love of wearing and gazing at uniform can both be, and were, construed as ‘feminine’ activities. Schneider shows how both acts were thus constructed in the debate that eventually weighed in against colourful and decorative uniforms, that prevailed in the name of masculinising the services The debate about sex/gender runs through the desire provoked and knowledge of the lore related to uniform – attached to the debate above but also running at a tangent to it, for the issue of whether same-sex-love requires binary distinctions of masculine and feminine is ever current in queer and homophobic discourse.

- Thirdly, the relative role of sex and ‘romance’ in relation to relationships between men is a debate that can fly around the debates, and closely related to the importance of male friendship and the distance or otherwise put between these relationships and feelings of ‘love’, in any and many sub-categories even.

- The role of other motives in the entry into male-on-male sex was ever present. Debates in Imperial Germany that mattered were those related to:

- corruption from above: This deals with abuse of hierarchical power (officer ‘corruption’ of the sons of workers or peasants leading to well publicised ‘orgies’) – and linked to discourses of sadism and the parliamentary discussion of the mistreatment of the lower ranks named at the time Soldatmisshandlungen, which could include non-sexual bullying.

- The crudity conceived to relate to the lower ranks could be used to explain male indifference to sex with men in the absence of women, but most interestingly is discussed in terms of male prostitution both in literary fantasy and in the courts. It to had a name: Soldatenprostitution.

- Corruption of the military by non-army ‘homosexuals’ in civil society. Interestingly enough those who claimed for militarism the defence of heteronormative masculinity in relation to martial values were also often those who believed these tough creatures were the prey of effeminate German men – empowered though by the wealth of the upper bourgeoisie. Antisemitism sometimes fed into this argument with Jewish homosexuals being fantasied as the corrupters.

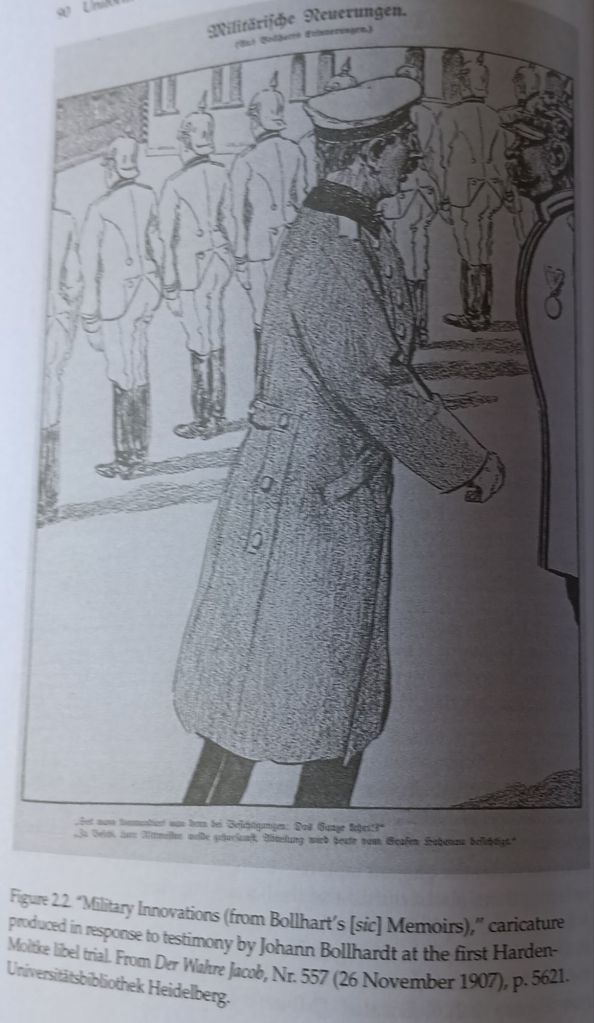

This cartoon lampoons a specific and named real commander who is accused of wanting to inspect his troops from the rear wirh theie coattails parted. See Jeffrey Schneider op.cit: 90.

Read this book if you want to know how history could be a more open discipline – enabled to cross the boundaries between different ways in which historical topics are discussed and related to lives not always represented in history. Of course the category of the homosexual had been created in this period and it is part of the story – though other issues – like class-based abuse and male prostitution clearly have a longer history behind them and do not require the category of the ‘homosexual’ to be part of the story.

Would be interested to know what you think!

All the best & with love

Steven xxxxx

[1] Jeffrey Schneider (2023: 16) Uniform Fantasies: Soldiers, Sex, and Queer Emancipation in Imperial Germany Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

[2] The serious games queer art plays: this blog is a reflection on a brilliant article in this month’s ‘Gay & Lesbian Review’ by Joseph Shaikewitz. – Steve_Bamlett_blog. Available at:

[3] Jeffrey Schneider, op.cit: 12

2 thoughts on “This is a blog about the role of the uniform in the construction of the object of queer desire in the contexts of the militarisation of social, political and psychosexual cultures based on reading Jeffrey Schneider (2023) ‘Uniform Fantasies: Soldiers, Sex, and Queer Emancipation in Imperial Germany’.”