The serious games queer art plays: this blog is a reflection on a brilliant article in this two-monthly offering of ‘Gay & Lesbian Review‘ by Joseph Shaikewitz.

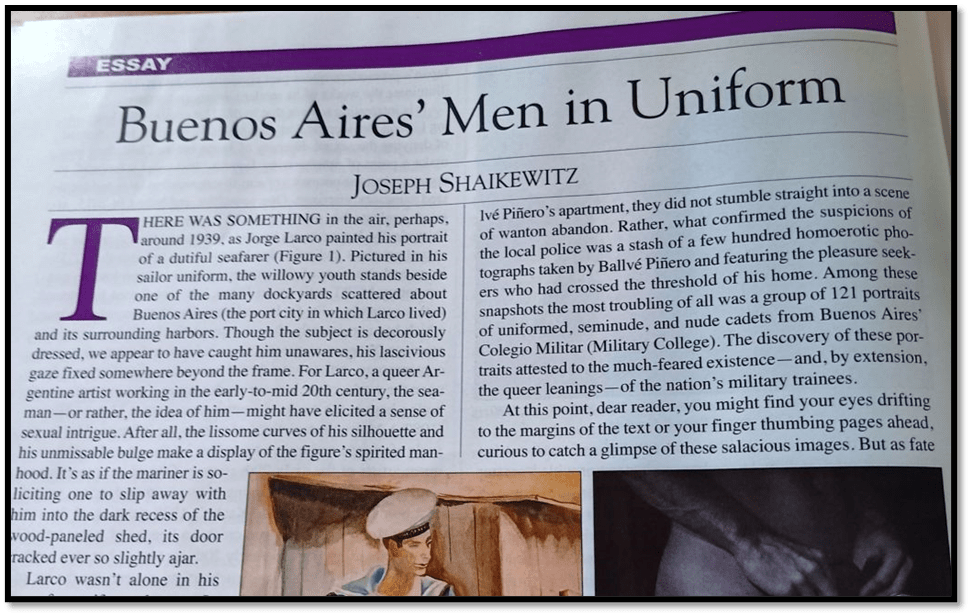

The article to which this blog owes everything: in Gay & Lesbian Review May – June 2025 Volume XXXII, Number 3, pages 32 – 35.

The present two-monthly copy of The Gay & Lesbian Review is very queer art savvy for its guest editor is Jonathan Katz, the finest curator of queer art shows ever. I wonder if he was involved in the selection of the essay writer in this copy because Joseph Shaikewitz is a PhD. candidate in Fine Art. I only wonder this, for Shaikewitz is a good thinker of the Katz kind; comprehensively knowledgeable not only in queer art history but in critical LGBTQ+ social analysis and activism. I couldn’t help but have to blog on some of its evidence and analysis thereof.

Let’s take Shaikewitz’s treatment of Argentinian artist, Jorge Larco, whose work seems particularly interesting as a vehicle of meanings that have circulated around the definition of male queer sexuality in the twentieth century. Shikewitz chooses him because his focus, and possibly that of his PhD., is the role of uniforms in the expression and performance of queer sexualities. However, I don’t intend to address uniforms, except where necessary as part of the content of specific paintings, here for I have decided to order one of the books the essayist recommends, Jeffrey Schneider’s Uniform Fantasies: Soldiers, Sex, and Queer Emancipation in Imperial Germany (I would have also have ordered Gonzalo Demaria’s Caceria where it not that it is not translated from the Spanish and I have not the skill or knowledge to read it in that language) , and will think about the issue of uniforms thereafter with intent to blog.

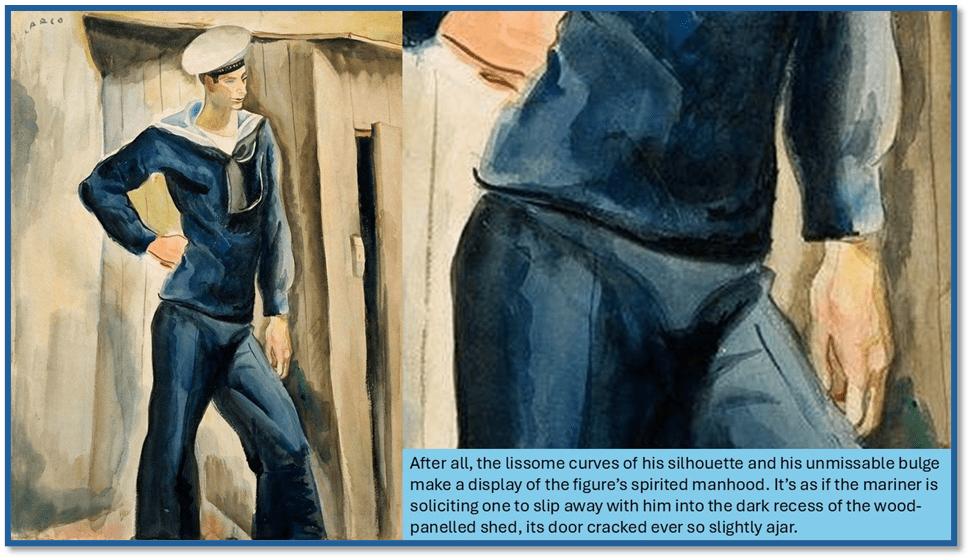

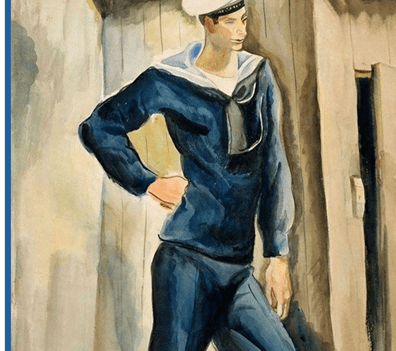

Instead I became interested in the meaning of queer art history and queer art criticism – how it signals, for instance, the evidence that makes it differ from academic art history of the ordinary kind, even where it is not (as most of it is) doggedly heteronormative. Hence i wanted to look at HOW the writer ‘reads’ the art of Jorge Larco, not only as art but as queer art with perhaps a different training of the eye behind it for the iconography and other coded languages of visual art. Let’s take, whsat he has to sat about the painting Marinero (1939). I cite Shaikewitz in the collage below, but not the part that triggered my interest in the kind of licence that queer viewers might take in interpreting this picture. For instance, he ”notices’ with respect of the sailor in the picture ‘his lascivious gaze fixed somewhere beyond the frame’. I just don’t see the painting thus – I cannot ‘see’ what in the gaze of the sailor is ‘lascivious’, nor even that its object is necessarily ‘beyond the frame’. What in there characterises the gaze as ‘lascivious’ other than some projected interpretation of his pose, stance and the suggestive, almost fashioned, dishabille of his clothing, especially that open collar. The arm gesture seems that of the teapot pose that has characterised queer men in art from the eighteenth century, but the eyes themselves could just as much, from what we see, actually show the absence of either focus or motive in the sailor’s eyes, as if he has taken up his pose in a mood of pure boredom at the exigencies of his life – often involving selling sex for money in the period, rather than looking to satisfy his own desire. The citation in the collage seems nearer the point. Here it is again with it explanatory prefatory phrasing:

… the seaman – or rather the idea of him – might have elicited a sense of sexual intrigue. After all, the lissome curves of his silhouette and his unmissable bulge make a display of the figure’s spirited manhood. It’s as if the mariner is soliciting one to slip away with him into the dark recess of the wood-panelled shed, its door cracked ever so slightly ajar.

By the time the writer gets here he seems to admit that his use of the adjective ‘lascivious’ earlier is only a possible reading, as he peddles back from stating the intentions of the artist with regard of exactly how to read the mariner – his look and purpose. Suddenly Shaikewitz is searching to justify his overall sense of the sailor as a pictur of ‘sexual intrigue’, invoking the man’s limbs and how he performs their exhibition to a viewer, taking time to concentrate on the unmissable bulge, which I have enlarged as a detail in my collage.

The trouble with Shaikewitz’s reading is that, though it can not be denied as a potential narrative version of what we see, it is also not the only narrative reading possible. There is no doubt that the mariner makes himself available for sexual pick up, but there is no means by which we can know his motive, which could, for instance, be that of prostitution, in which he adopts his pose as a means of advertising. But the reason for that weakness is that it is not essentially about queer art but queer behaviours that might or might not be being revealed.

For me, the painting’s aesthetic strategy is only in part revealed by Shaikewitz, precisely because he sees the narrative only in terms of the representation of the real elements within a narrative. Nothing can be seen as merely the process of queering the certainties that trying to find a realist narrative requires. For instance, think again of this part of Shaikewitz’s story:

It’s as if the mariner is soliciting one to slip away with him into the dark recess of the wood-panelled shed, its door cracked ever so slightly ajar.

Is it enough for an art critic to reference a ‘dark recess’ in without taking account of the painterly issues of creative process involved: issues of design, depth and volume, and their relation to areas of tones and shades – darks and lights, shadows and solids. The painting for me is all about nuances of recess and bold forefronting of frank volumes. This is how we read queerly – for the painting seems to me to contrast the hardness of certainties and the softer feel of nuances.

Look again at the patterning of light and dark without which there could be no ‘unmissable bulge’, but such bulges are, as any queer man will tell you, never certain evidence of anything real – they are like a game played with illusion played against the hope, self-delusion and, expectation on the side of viewers and viewed. There is a dark recess, but it is not shown without nuance in the rest of the background with its stains and shadows, which are difficult to distinguish between each other.

This sailor, too, is full of nuance – not even between whether his show of desire is in the realm or advertising something for sale, but also because these sailors were also potentially dangerous, as liable to turn against as they might offer pleasure to the men they attracted. Hands that are extremely large might attract, but in resting on hips, they rest on hips as FISTS.

In a sense, I think, it is strange that the very intelligent essay by Shaikewitz does not focus on the ambiguity of this shadowing sailor than his surface sexual appeal to a viewer ready to admit that, at least to himself. Shaikewitz says;

This is one of the ambiguities of the masculine desired when it applies to uniformed state servants – the police and armed forces in particular, since firemen did not have a remit set by civil law – but the other is that all men might be dangerous when they become the object of desire and become conscious of that and the ambivalences in them that arise in response to male solicitation for sex or affection.

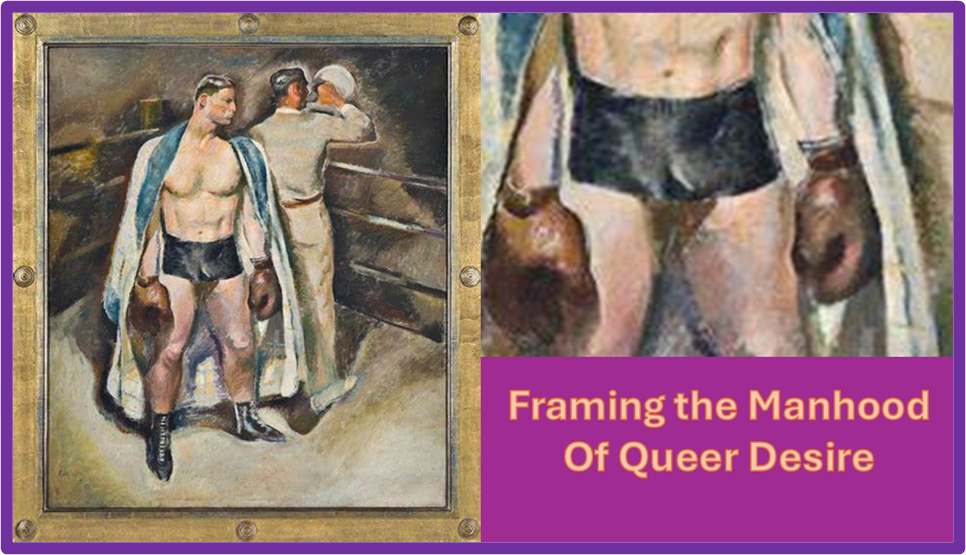

For instance, let’s take another painting by Jorge Larco, which shows a male with an ‘unmissable bulge’ but not one protruding from a tight uniform. The bulge is even more unmissable than that in Marinero, and, although it is, none the less, a total illusion of light and shadow that produces the look of volume and depth in tne boxer’s shorts, it is the more skillfully and, from distance, realistically done. But that protuberance is framed by huge bulbous boxing gloves that defend that which they frame. These huge hands are made the more forbidding and alien by the size of the gloves, and the fisting of the one on our left. My point that to paint the object of desire is to paint also the object of potential threat and that that challenge is painterly and not just the reality of repressed lives.

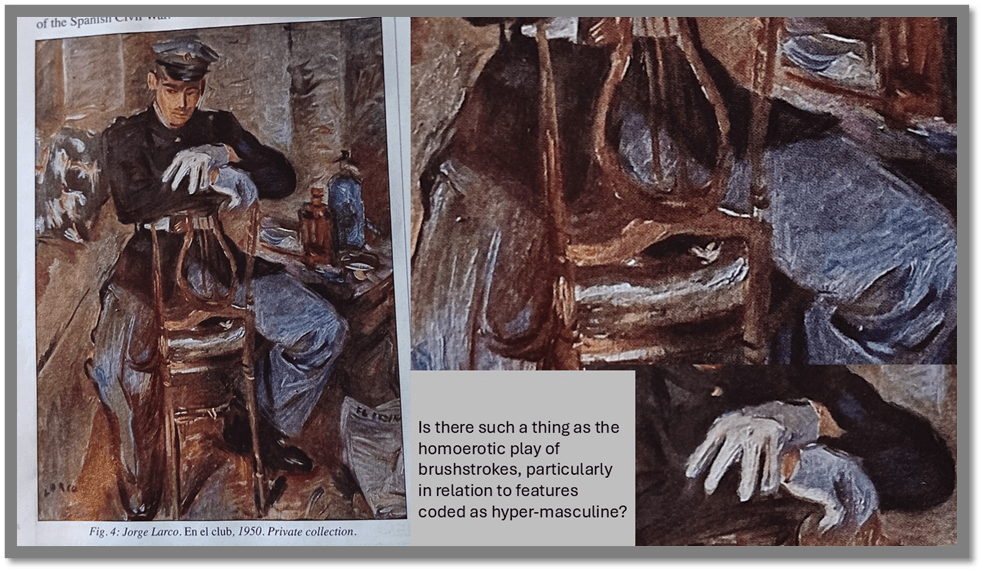

Sometimes the threat is more sinister, as in a beautiful painting picked out by Shaikewitz by Jorge Larco En el club (1950). Here desire is a very painterly and aesthetic product. in my collage below I caption it: ‘Is there such a thing as the homoerotic play of brushstrokes, particularly in relation to features coded as hyper-masculine?’. What I mean by this question is to draw attention to the play of brushstrokes that comprise this military man’s trousers, so extended and enfolded that his legs are massively the centre of attention. The swirl and mylti-directionality of those brushstrokes catch the eye and absorb the interest of the viewer and blur the boundaries of the thing painted, especially in the leg on the viewer’s right. And then the crotch area where those playful strokes are mirrired 0 they lie within the gap formed by the splaying of the dark blue military coat and are seen through the orphean lyre back of the chair he straddles, perhaps even rides like a cavalier. The crotch area lies just behind the represented ‘strings’ of the lyre on which Orpheus might have played such music with his subtle fingers.

But the hands here too are treated in a painterly way, and their role as white patches (he wears military dress uniform gloves) is to cap and press down on the area of blue tonal variation beneath them. I find them bot , especially the left side hand which has crossed to penetrate the recessive shadows on the right of the picture, ominous of something tougher than the caress the other hand might also promise. Again, like Marinero, his gaze is indirect – refusing to acknowledge the desire it inflames.

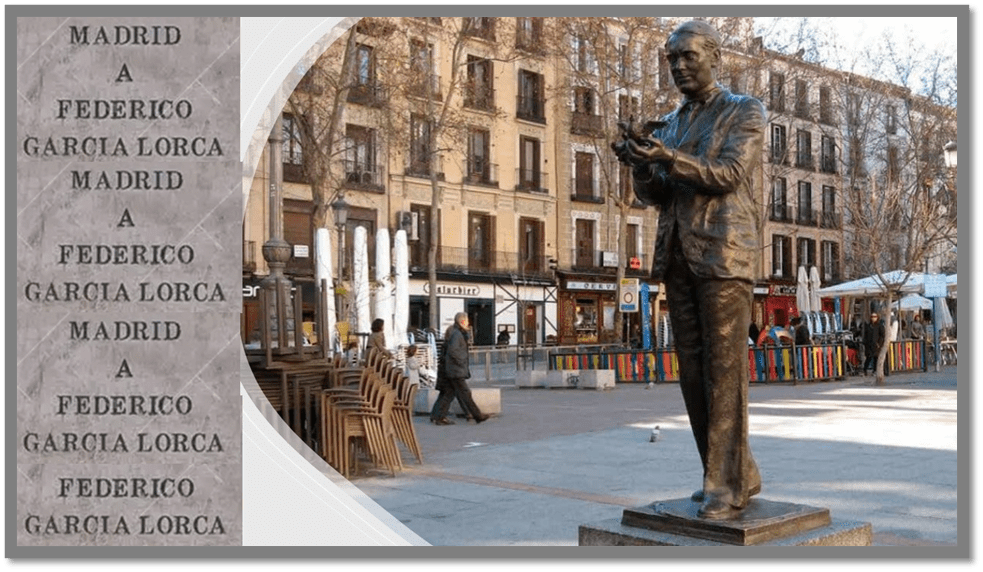

What I sense, that isn’t quite what Shaikewitz does, is that desire is complicit with threat in the very image and the process of its own making that it lays open to the eyes – painterly plat held back by imagery of constraint. The men of the period Shaikewitz deals with would entirely understand the game they play of flirting with the masculine images they also feared. Such a tension is highly present in the poet, Lorca, who visited Larco in Argentina. In earlier blogs (see the one at this link) I have shown the tension Lorca felt about sex-role playing in male desire, even running to despisal of feminine males, that must in part have been imposed on his psychology by the male culture about which he is so ambivalent. Yet poets must show sensitivity, however feminine the culture brands such displays, as might be seen in the poet’s memorial in Madrid:

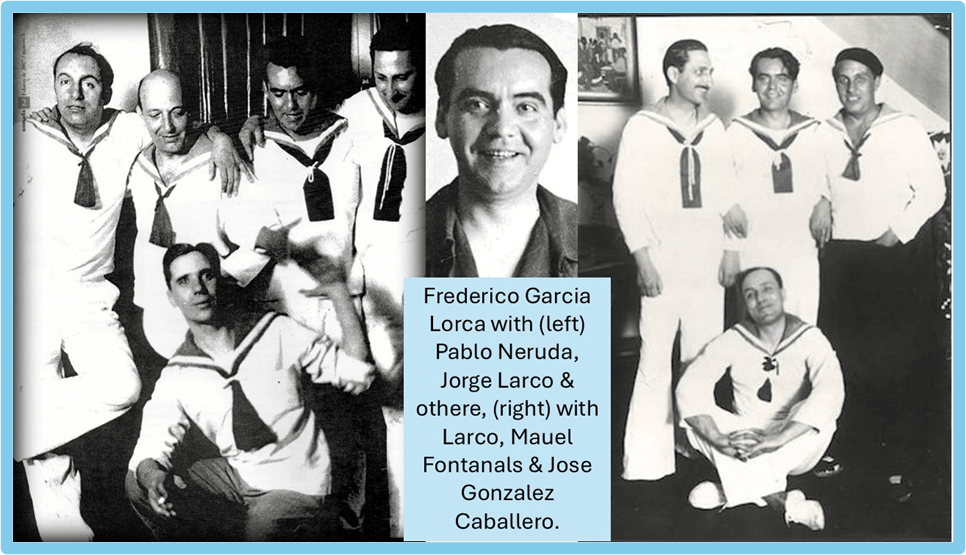

But Lorca too played the masculine game with his poet comrades in South America (even I was surprised to find in the photograph below – the other (right in my collage) than Shaikewitz uses in his essay – Pablo Neruda). The camp gathering of male poets and artists below in sailors’ uniforms (none of which are but a theatrical costume) shows that queer men oft controlled uber-masculine imagery by ‘camping it up’ (see my silly blog on this).

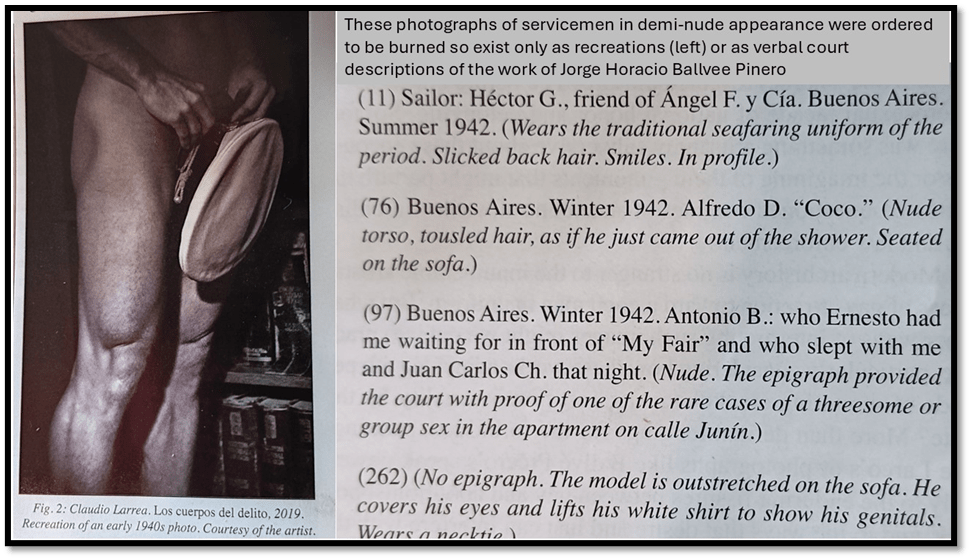

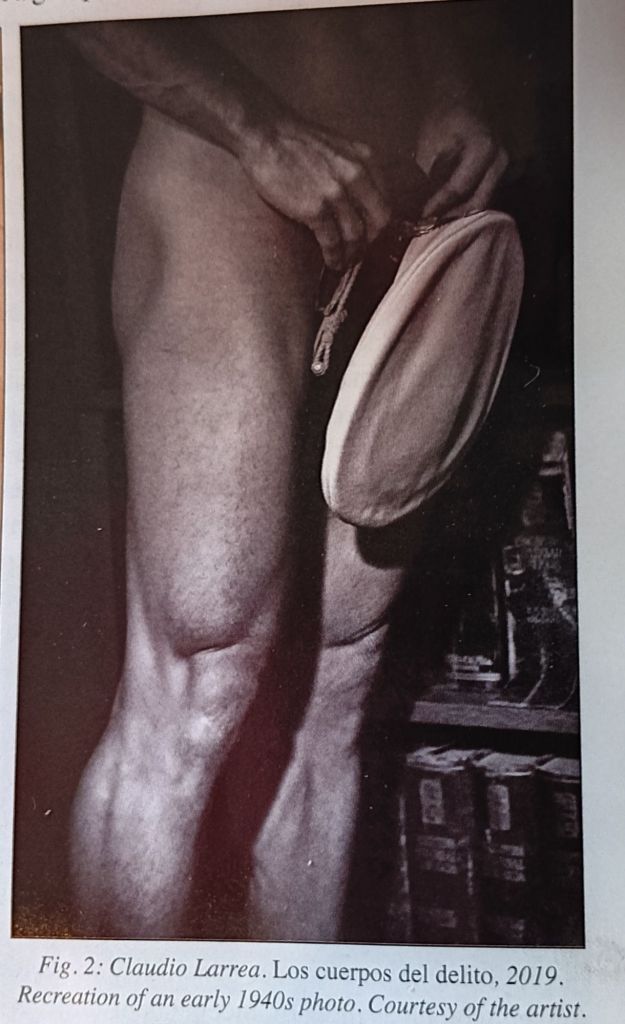

But there is also a sense – clearer to men who had sex with men in the time of these queer men, that uber-males too were as happy to not be confined by binary labels of gay and straight, homosexual and heterosexual, though perhaps less flexible with the more entrenched binary male – female. Shaikewitz instances the photographer Jorge Horacio Ballvé Piňero. His photographs exist now only in recreations by later photographers done from court descriptions by the very court, unwilling to show them to jurors, had them burned (some of these from Shaikewitz’s article are in the collage:

The one recreated by Claudio Larrea in 2019 (Les curpos del delito)lacks the deeper threat of Larco’s painting – the sailor hides his penis behind his sailor’s hat – and this may reflect the fact that these young men were ‘uniformed, seminude and nude cadets from Buenos Aires Colegio Militar. In Argentina the photographs hurt populist nationalists because they sensed no contradiction between queer imagery and the trappings of a nationalist military in preparation. i will think of these when I come back much later in a blog to the issue of uniforms 9when My book atrrives).

Meanwhile above is the bigger picture of the Larrea photograph – and yes the hands are huge as in Larco’s paintings (and John Minton’s come to that – see my blog at this link) but they are so gentle and playfully defensive than threateningly so.

Bye for now

Love Steven

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

One thought on “The serious games queer art plays: this blog is a reflection on a brilliant article in this month’s ‘Gay & Lesbian Review’ by Joseph Shaikewitz.”