Visualising passion – approaching J.M.W. Turner’s attempt to capture the embodiment of desire in Turner’s Secret Sketches edited by Ian Warrell (2012) Tate Publishing.

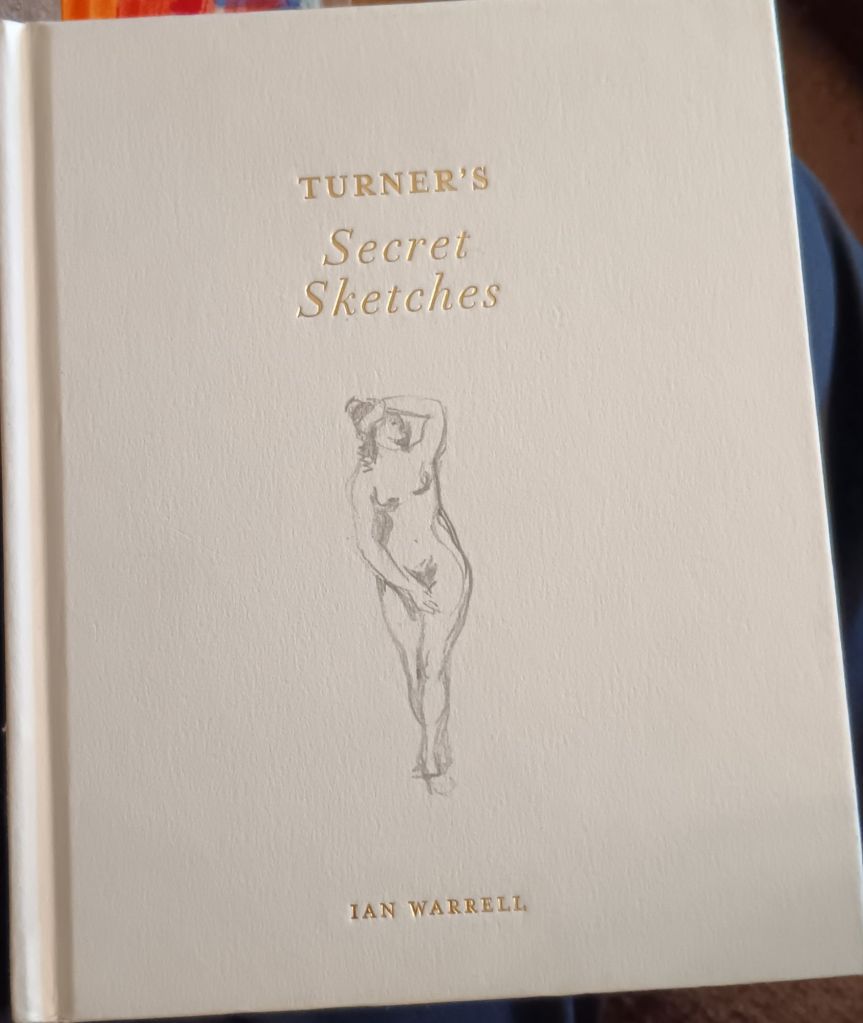

I am still cataloguing my books, abandoning many along the way, and have reached book number 3744 of the books I am keeping. The book is Turner’s Secret Sketches, edited and introduced by Ian Warrell in 2012 for Tate Publishing. The drawing on the cover of this book tells one little other than that the book contains sketches of naked women, and that what is secreted, given the way the woman in the cover drawing holds her hand over her vagina, has something to do with Turner’s heterosexual experience or fantasies of the same.

But we make this assumption at our peril. Indeed, not all the graphic work exhibited in this book, all taken from the sketchbooks Turner used to capture the imagery that he would later use in his paintings, can truly be said to be ‘secret’ or intended to be such. For instance, take the famous watercolour from the ‘Swiss Figures’ sketchbook. Warrell describes the picture as a response to the sexual freedoms Turner at the age of 27 discovered in his travels in Switzerland. Warrell admits that it is not easy to describe the figures on the bed , even indeed down to the sex /gender of the figure at the rear, who is obscured either by the fall of the lighting represented in the room or by a deliberate artistic methodology. Nevertheless, from the off Warrell sees the picture as of ‘two figures, apparently in post-coital abandon’. His later comment about the pale figure nearer the ‘front of the picture that her ‘hand seems to caress something – perhaps his penis’ shows he has little truck with the idea that there are two women in bed here.[1] A rather different view is given of this picture by Turner’s intelligent 2016 biographer, Franny Moyle. She finds ‘post-coital’ atmosphere here too but does not assume is coitus that has been performed by or just by the two figures. She thinks it may be possible that after thruple-sex with the two women represented here – prostitutes – Turner has slipped out of bed to draw the remaining persons, to their delight (or has imagined such a scene).

What is intelligent about Moyle’s description is that she shows hat Turner put a great deal of work into this image, saying it is ‘worked up to a relatively finished degree not just for the personal pleasure of completion, but because Turner made up the watercolour with a client in mind’, just as Henry Fuseli worked up erotic pictures for private clients. And this fits with the purpose otherwise of the Swiss Figures Sketchbook, to make a record of the character of the Swiss people: ‘… dedicated to capturing the ordinary working folk of the region, defined by their national dress’. This fits with the lit focus of the picture wherein:

He lovingly colours three large-brimmed, flat straw hats, suggesting yet another participant in the sexual revelry who has perhaps left the party. He delicately outlines the women’s shoes, with low heels and buckles, lying on the floor, their red corsets and blue-grey skirts.

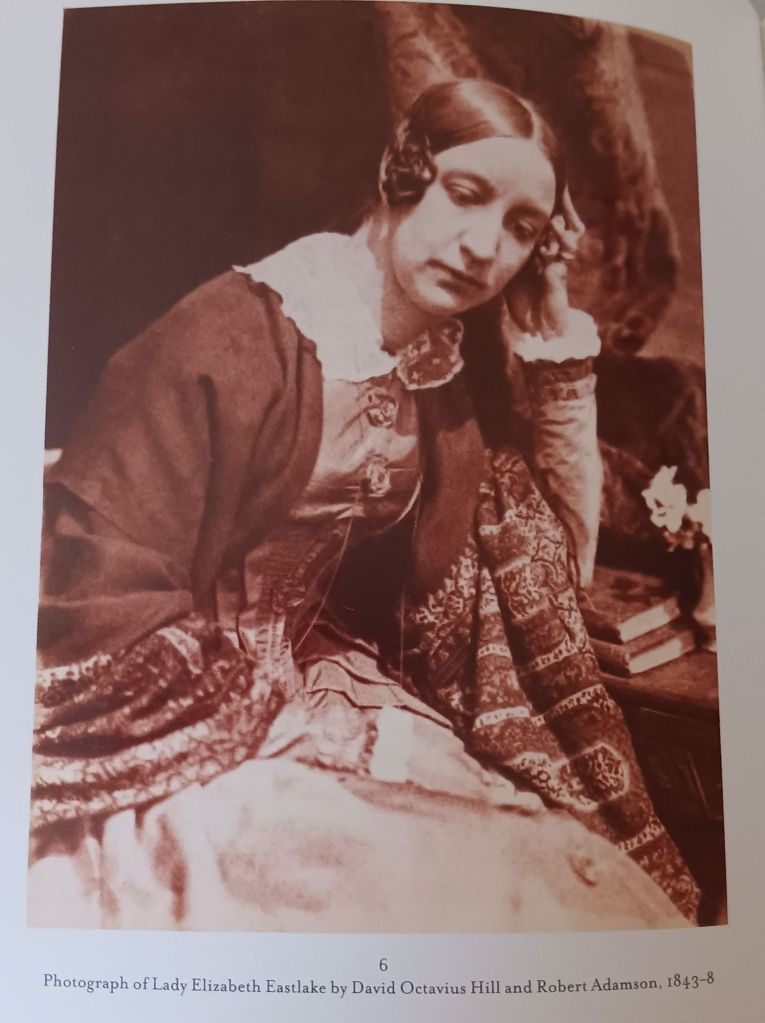

This is an image that is rather more nuanced than Warrell’s and more open to diversity of interpretation, even of sexual practice, and even more painterly! And that I think is the issue. we jump too soon to separations of Turner, whose sexuality was not so distant from the average of the lax first decade of the nineteenth-century. My own feeling though is that Warrell may, despite is nuanced look at John Ruskin’s role in suppressing – perhaps even putting to the fire – the erotica of Turner (if he did and Warrell doubts he did), is still keeping alive the terrible splitness of Turner in the eyes of Ruskin – as a man who had a ‘dark side’, or what Victorian moralists interpreted as a dark side. Warrell does point out that the best defence of Turner was by the feminist liberal, Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, below in a photograph in Warrell’s book (op.cit.: 44).

She, he says, ‘questioned Ruskin’s fitness as an authority on painting, ans accused him of a narrowness that sought to reduce ideas to absolutes, instead of respecting diversity’. If that is true of him in Modern Painters, how much more so in relation to constructions of the sexual. When Turner wanted to make a crude or rude drawing (however you interpret both the foregoing adjectives) he could do it. Witness below his sketch of a lady ‘giving head’:

Also he could invent sex scenes that are no more interesting than heterosexual (or passing as such) schoolboy doodles as in the collected feet sticking out from under a sheet below.

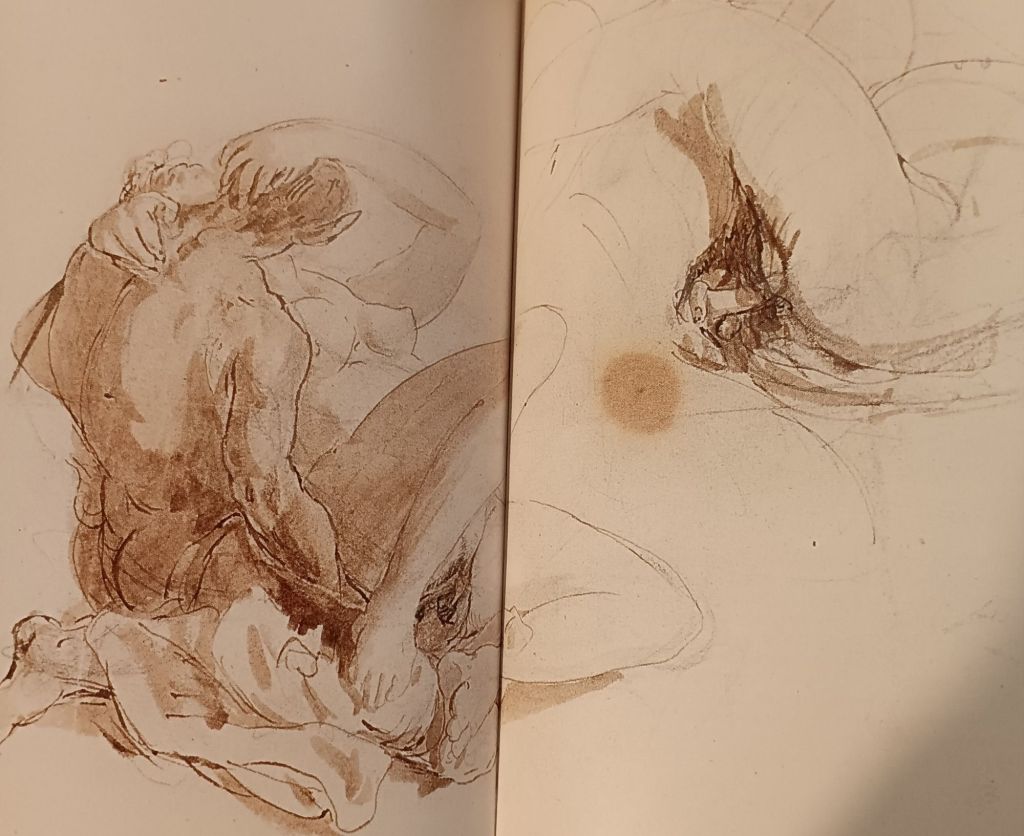

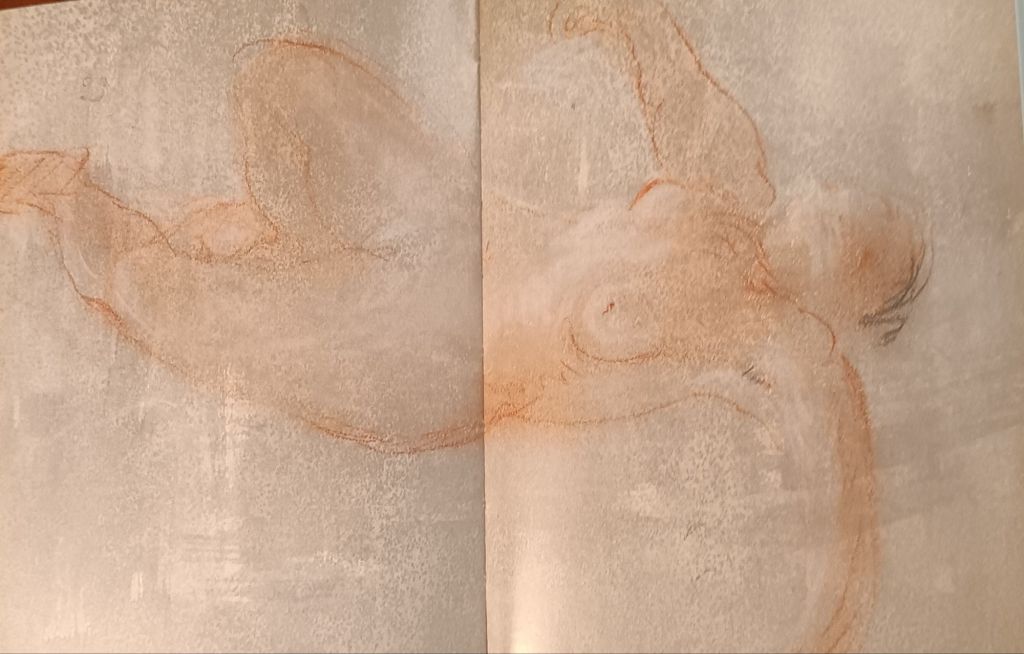

However, in the picture below we see both modes (the schoolboy curious and the painterly. Below on the right, he makes a rough sketch of heterosexual coitus a tergo, one crudely drawn, with a larger phallus than that in the heterosexual fellatio scene above. On the left however he embodies a coitus a tergo scene without the presence of drawn sexual organs, yet it is the more passionately invested picture.

The passion is a product of the use of shading that crosses the delineation of the boundaries of bodies and the dynamism of the action lines that, in order to show a figure in motion delineate its curves as in two superimposed bodies – as in the rear of the male torso . The aim is to show passion embodied – even in the cusp between bodies and this is an aspect of great drawing, not necessarily great imagined sex. Two bodies are not required to portray this, nor need they meet stereotypical criteria of sex/gendered beauty, as in another highly finished nude Warrell collects from the ‘Woodcock Shooting’ sketchbook of 1810-12..

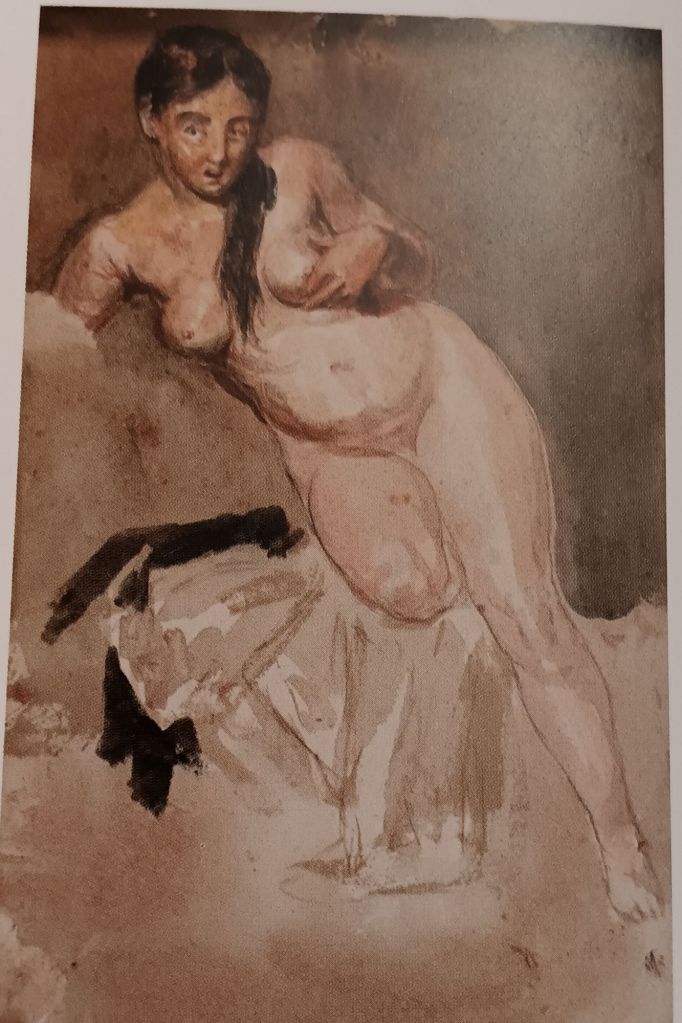

This is perhaps one of the finest sketches of embodied auto-eroticism available. Shading and colouring all contribute to the gross shaping and out-fleshing of the body, even the fall of hair between the breasts. The cupping of the breast is sensual because the hand is felt to touch the nipple, the touch even shaded. . This woman may look outwards but her gaze is amazedly internal or at a mirror – , her joy is in the shedding of the rather fine dress beneath her. We are tained top see such pictures as heterosexual male fantasy, but how much can that be justified, for this picture comes from painterly work not fantasy, it loves the body as only the person in it could so fully.

As I look through these sketches again, I feel Iurner working with paint inventively, especial in the range of reds, pinks and vermilion, and almost abolishing the delineation of body limit for fleshly feel that even inhabits the background wash below. Colour and omission of any marks in focal spaces, in a body that grows to the impossible size of its desire and yet is constantly penetrated, as if, autonomically (as an involuntary act of self-desire in which the gaze of the other can be eliminated).

Even when body is delineated, Desire invades it as a drawn item of laid-over fabric in rich tomes of red and its spectrum, then mirrored in a blush which crosses the boundaries of the neck. This is truly erotic and again cannot be easily interpreted as a product merely of the male gaze. If it were Turner would have never relished so much as he clearly did the sharing of the same space of the spotted dark markings – perhaps intending to represent pubic hair partially as well as shadow but perhaps not – and the blushful Hippocrene of the red shading.

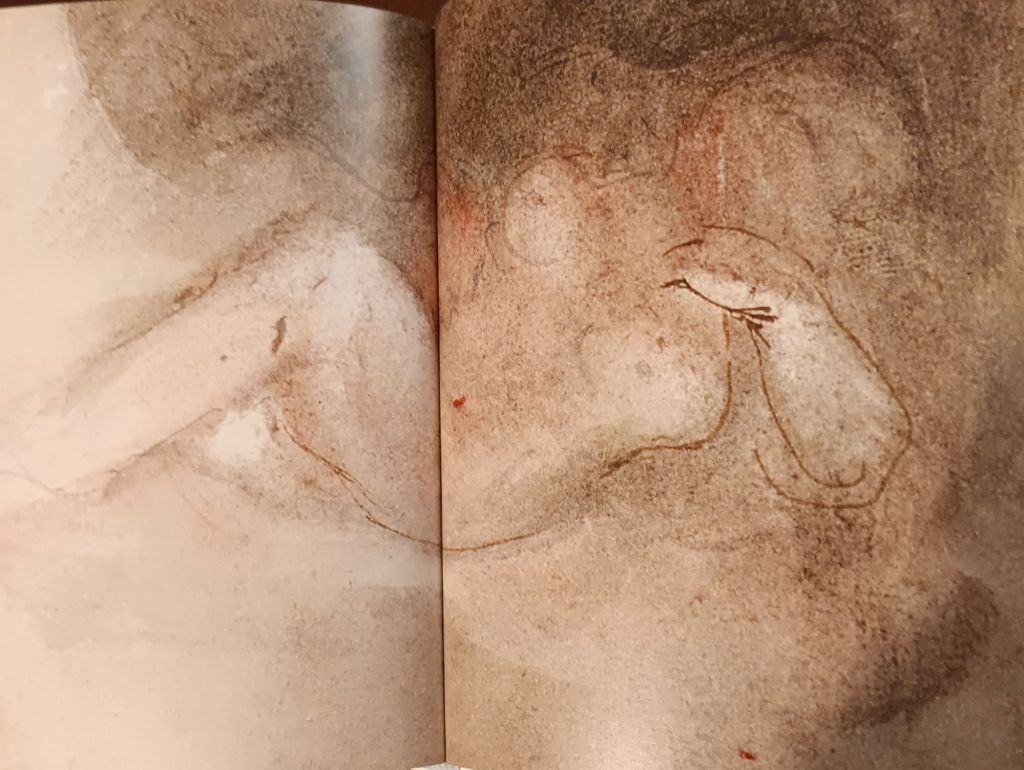

Turner seemed to interrogate figure and background, often in what seems as his fascination with breasts, which are drawn with the right breast falling, the left more alert. The writhing motion of the legs and the intention in the arm obliterate the head of this woman, and yet no object of passion but the subject’s own body exists. here, for too long we have intuited male gaze. My queer women friends have too often corrected me on this assumption. However, this is not the best example for my point, for sometimes I see evidence of a head about to lay itself on this figure’s lower torso and kiss it, as a ghost might.

Even more obliterated is much of the body, suggested by faint pencil below, apart from the pale red and pink blushly marks of paint that cross real (pencil line real) or imagined (by the gaze of the viewer at a non-finito image) boundaries below in imagining this woman, except that her vagina appears as a kind of bleeding wound, blood-red and dominates the picture and obliterates much more than is already non-finito. People too long have resisted seeing this image as complexly as they would had it been painted by a woman.It is likely now that some may see the male gaze exalting over a raped woman here. I don’t.

In some pictures (I give only a detail below) body has been reduced to colore abstraction, yet I think we are meant to see a woman on a shrouded bed in a lavish sun-soaked room of near gold. Is it Danaëa? If so it might be a male gaze picture. It actually comes from a set merely called Colour Studies. Hence, my point. This is the painterly narcissism (I do not intend value judgement here) in which sex/gender in painters gets dissolved in bigger issues of form and beauty.

It is useful to look at these books again.

Bye for now

Love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

________________________________________

[1] Ian Warrell (2012: 60) Turner’s Secret Sketches, London, Tate Publishing.