What Olympic sports do you enjoy watching the most?

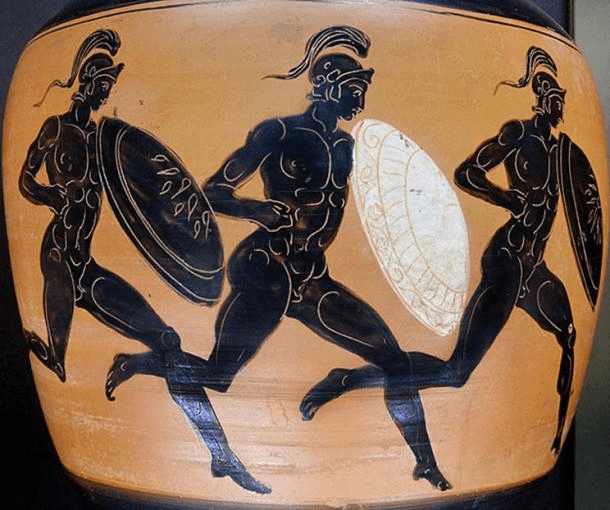

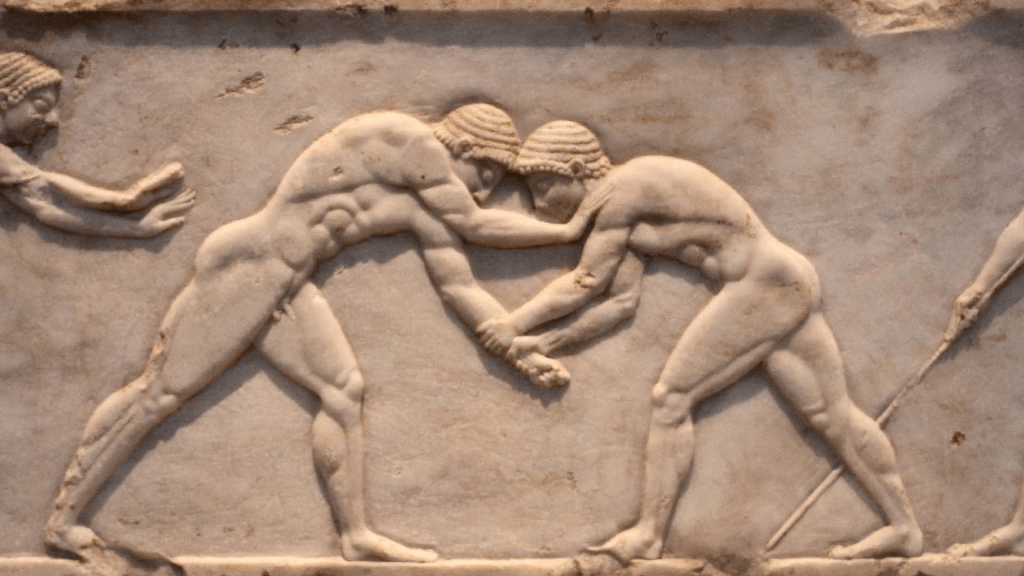

Why do we watch sport? The question presumes an answer: we watch it for enjoyment, for pleasure! Since, however, I don’t watch sport if I can help it (yes I know that fulfills all the stereotypes of queer men), this must mean that the pleasure sport affords is variable – since I know, for instance, that I am not alone in choosing not to watch sport, or being bored by it if we do catch it by error or contingency. There must be some reason behind the variation rather than just a universal drive to pleasure. In its origins, the Olympics were an elite set of sports, played by an elite aristocracy, trained for the roles it involved – usually the tasks in it were aligned to military purposes.

David M. Pritchard (2020) points out that even when Greece became a democracy, sport remained a participatory activity for the elite and merely a spectated activity for the non-elite sportsmen and population. He argues that the connection of sports to the aims of military virtue actually bought the admiration of non-elite Greeks of sporty elites. For the non-elite democracy meant access to a role in war but not a leading role, for that needed, as they perceived it, the rigour that went into aristocratic training to lead military campaigns, and build the ‘virtue’ associated with it. A citation from the abstract of Pritchard’s paper will suffice, where he argues a case for re-examining ‘the neglected problem of elite sport in classical Athens’ and why it was not swept away with the oncoming democratic reforms in Attica:

Democracy may have opened up politics to every citizen, but it had no impact on sporting participation. Athenian sportsmen continued to be drawn from the elite. Thus it comes as a surprise that non-elite citizens judged sport to be a very good thing and created an unrivalled program of local sporting festivals on which they spent a staggering sum. They also shielded sportsmen from the public criticism that was otherwise normally directed towards the elite and its exclusive pastimes. The work of social scientists suggests that the explanation of this problem can be found in the close relationship that non-elite Athenians perceived between sporting contests and their own waging of war. The article’s conclusion is that it was the democracy’s opening up of war to non-elite citizens that legitimised elite sport. [1]

Pritchard does not address why non-elite males supported the solidification of their role in sports as that of spectators rather than participants, but we might extrapolate from his evidence that in evaluating ‘sport to be a very good thing’ and the fact that they ‘created an unrivalled program of local sporting festivals on which they spent a staggering sum’, they also sought to find a pay-off in pleasure for watching that elite serve ends they honoured too. Aristophanes in his comedies even allows that watching the young naked men perform in the gymnasium gave his male lower class characters a sexual thrill – it seems an assumption of the comic effect in relation to his non-elite characters, about which he is uncritical and remains jovially complicit. It would seem that if spectator sport grew from a willing complicity that the elite fighters for your nation needed to prove themselves competitively that a spectator might feel associated with that elite precisely because they identify with the process of achieving the best in those they allow to represent them in the most important of the state’s functions – its defence from external attack in war.

The link to military training has been long broken, but only recently in the long duration of history. Thus, philosophers have looked for another reason that sport is a visual pleasure for the non-sporting or for the lesser-enabled to be sporting in body at the highest level of attainment. Some philosophers have sought to compare watching sport to the viewing of artwork; specifically C.L.R. James in his characterisation of cricket. However, others deny that sport, though it may have an aesthetic aspect that produces grace in a range of art genre areas – ritualised motion, repeatable form, drama, and so on – is art. Its aesthetic quality is, they might say, at best a by-product, not a primary goal of sport. Others see competition, even in its ugliest forms, as so essential to art that the aesthetic aspect is almost a contingent accident in the activities involved:

Eliseo Vivas (1959, p. 228) contends that, unlike aesthetic experiences, sport cannot be experienced disinterestedly. To do so, one must bracket an essential feature of sport: competition. For Maureen Kovich (1971), if athletes and spectators focused on the aesthetic aspects of sport, their preoccupation would be the observation and creation of art in movement rather than on scoring and winning. The main purpose of sport is to meet physical challenges and to compare oneself to others in doing so. [2]

Philosophers, however, have, the Stanford Encyclopedia article insists, seen a new way to explain the individual and social pleasure of sport. Strangely their explanation could also explain the Greek non-elite classes investment in watching sport too – we watch it to envisage in another realm – values and meanings we find missing in everyday life, either that of our own life or that of our ruling elites.

Kevin Krein (2008) and Tim L. Elcombe (2012) have argued that, like art, sports convey values and meanings external to sport that represent, or present an alternative to (in the case of non-traditional sports such as climbing and surfing), the culture in which sport practitioners find themselves. In Terrence J. Roberts’ (1995) view, athletes are ‘strong poets.’ They expresses something about our life situation as embodied agents (Mumford, 2014). Drawing on Nelson Goodman (1978), philosophers such as Edgar, Breivik, and Krein understand sport as worldmaking, that is, sport embraces and refigures symbolic worlds outside of sport, opening up new ways of describing, or making, such non-sporting worlds. Sport provides resources for re-describing the non-sporting world. [2]

If watching sport allows us to imagine we are seeing the potential of a better world, where even the ugliness of some part is motivated to good meaning – the extension of human power to give itself to some ideal other than appearance, or selfish self-regard, for instance – then it enables our pleasure to be justified at the highest level. Lots of the discourse of sports commentators could be evidenced to support this idea, but I suspect a lot also might not. I do not watch sport – as I have said – so cannot comment.

Is the reference to Olympic, rather than to other sports domains, important in this question? I wonder. So bound up is the Olympic ideal, if not the reality of Olympics Committees often making grubby decisions based on financial gain, with melding together nationalist aspiration with an international ideal, that I suspect the last named philosophers may have a point that the Olympics aims to open ‘up new ways of describing, or making, such non-sporting worlds. Sport provides resources for re-describing the non-sporting world.’

Such views are sometimes promoted in the art used to frame the Olympics – those in London and Paris being exemplary – that embrace vision beyond that of current shoddy statecraft. But I think here, as elsewhere, the reality is complex.

Bye for now

Love Steven xxxxxxxxxxxx

____________________________________________

[1] Pritchard D. M. (2016) Sport and Democracy in Classical Athens. Antichthon. 2016; 50:50-69. doi:10.1017/ann.2016.5 Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antichthon/article/sport-and-democracy-in-classical-athens/1B7E6CA74614F45184DF93E4D6C4F4B6

[2] ‘The Philosophy of Sport’ in a section related to the aesthetics of sport (2020) in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sport/#AestSpor