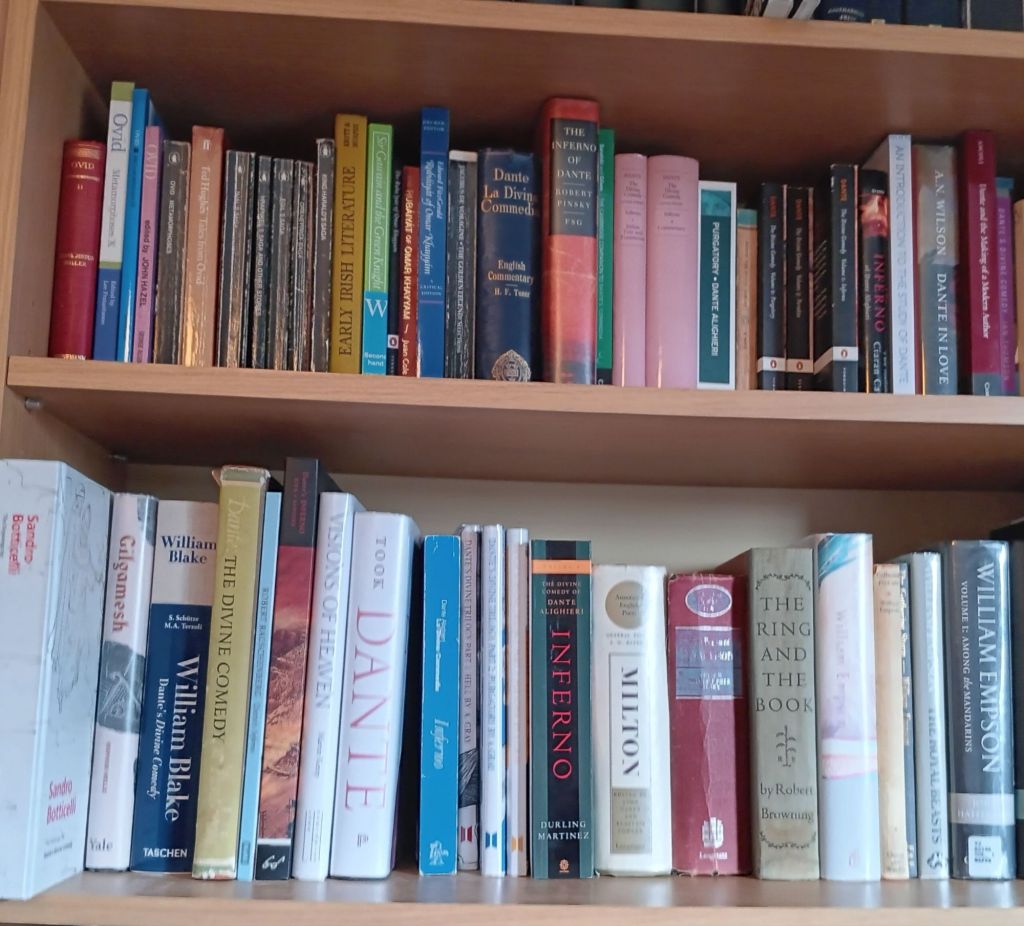

I could be Dante because, as yet, I have read only extracts of what is considered by some the greatest poem of the modern world. Moreover, I have been preparing to read it for so long that the task of cataloguing these volumes is raising my cultural guilt to new and higher levels than ever. The volumes are haphazard. I have collected the ones I didn’t already have since I retired in order to read the classic text ‘properly’ (by my nonacademic standards of course). The collection consists of parallel Italian / English texts, commentaries, and lots of translations and versions text, including Alasdair Gray’s completed in the year of his death. He used to pride himself on not being able to read Italian at all, but managed the version from compared translations.

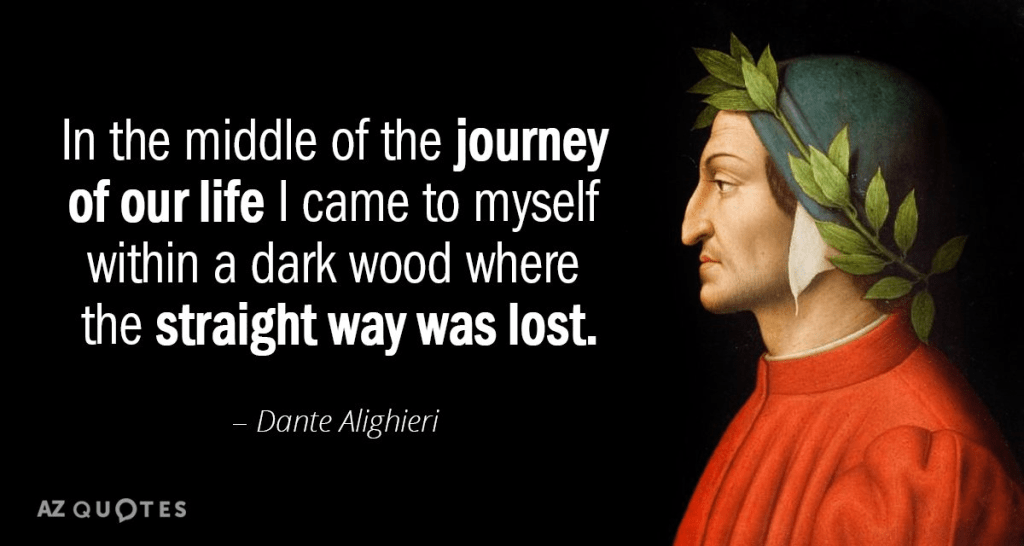

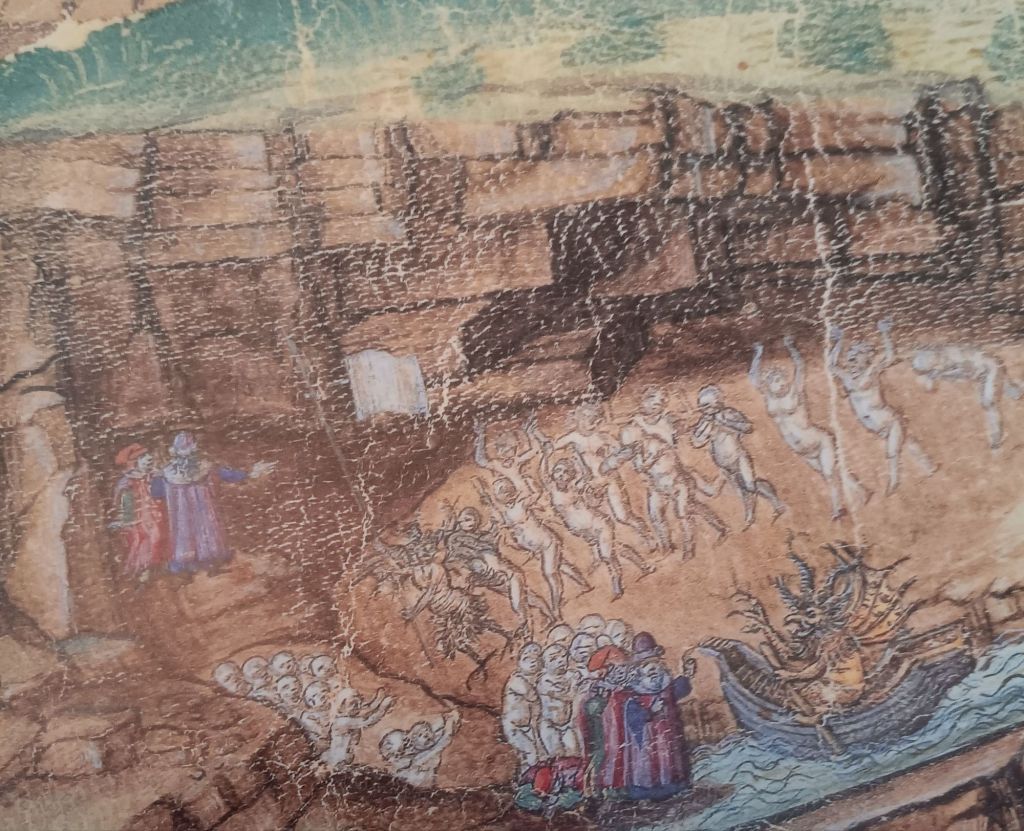

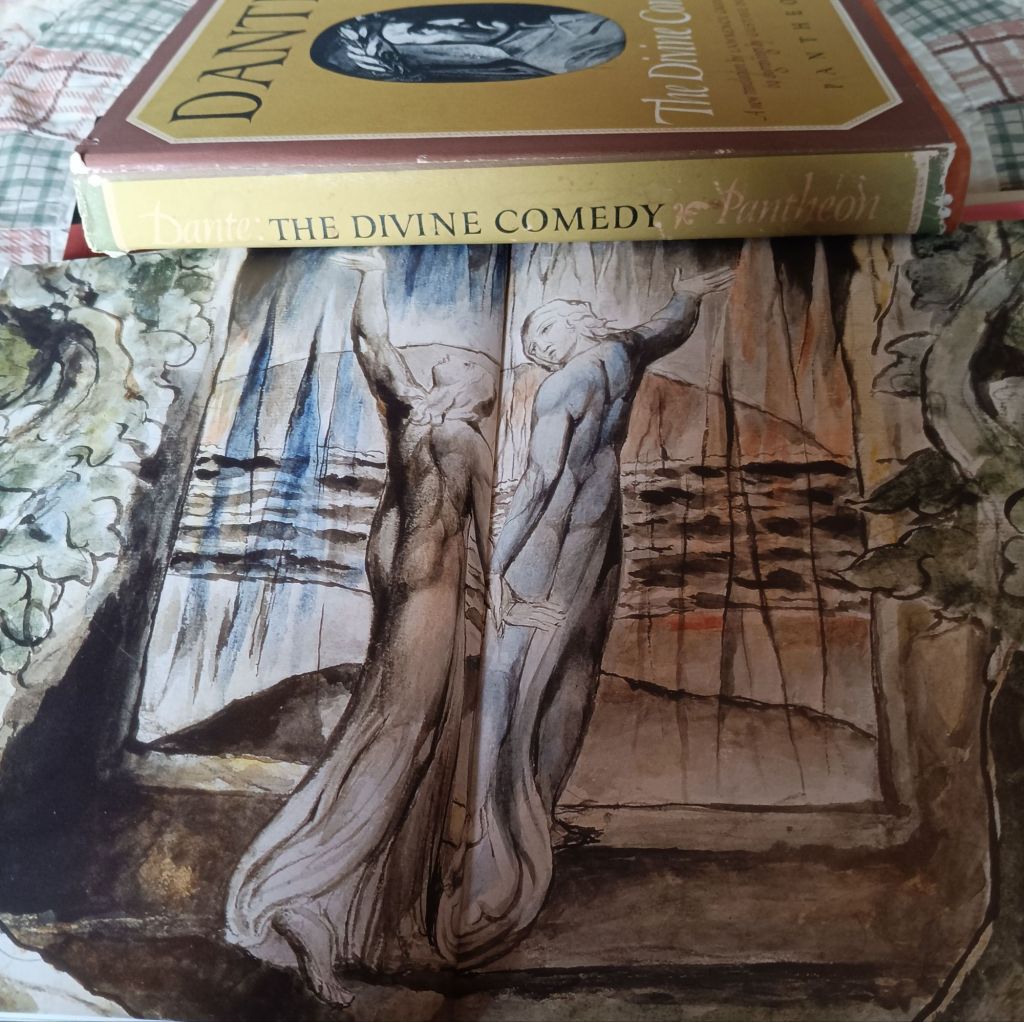

Amidst the collection of books are ones on illustrators of the poem that range from two August volumes on medieval illumination, through Botticelli, William Blake, Gustave Doré to Rauschenberg and the anachronistic drawings of Sandow Birk, where Hell is clearly located in North America.Why Dante? Why not? In the opening lines, Dante famously tells of being in ‘the middle of the journey of our life’.

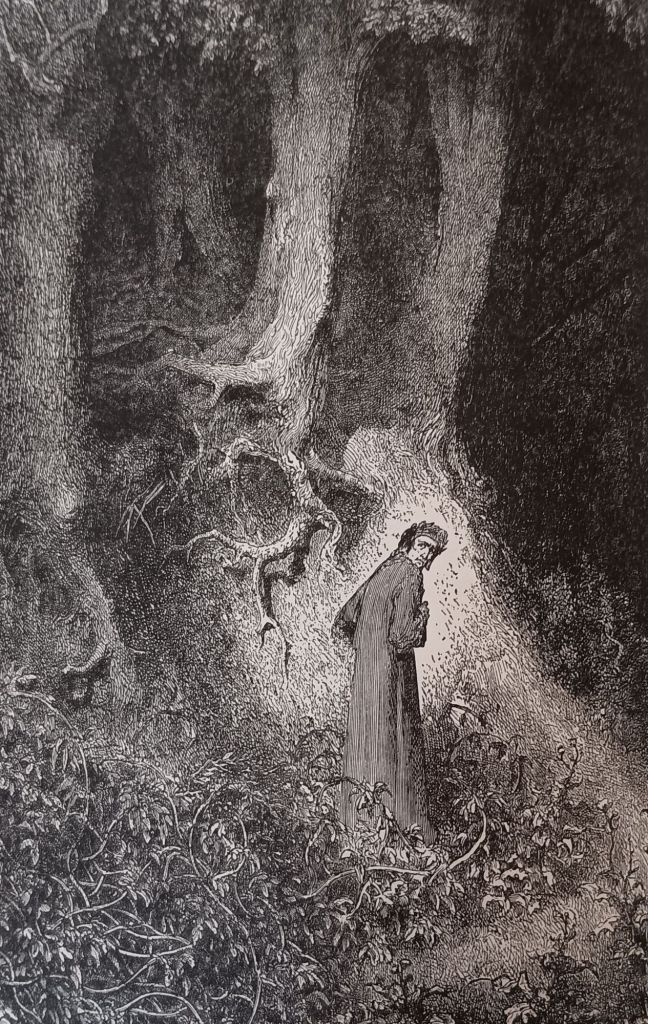

Commentaries from The Reverend Tozer in 1901 to Charles S. Singleton show that, set in 1300, Dante was 35 and considered that the middle of ‘our life’ was precisely that for Biblical authority [Psalms 89[90 verse 10] considered the human course as set to end at 70 years of age. So here’s another reason to be Dante. One gets back to being in media res [in the middle of things], and with time to make a little more of life than one had done the first time round. Gustave Doré has Dante’s feet mired in vegetation.

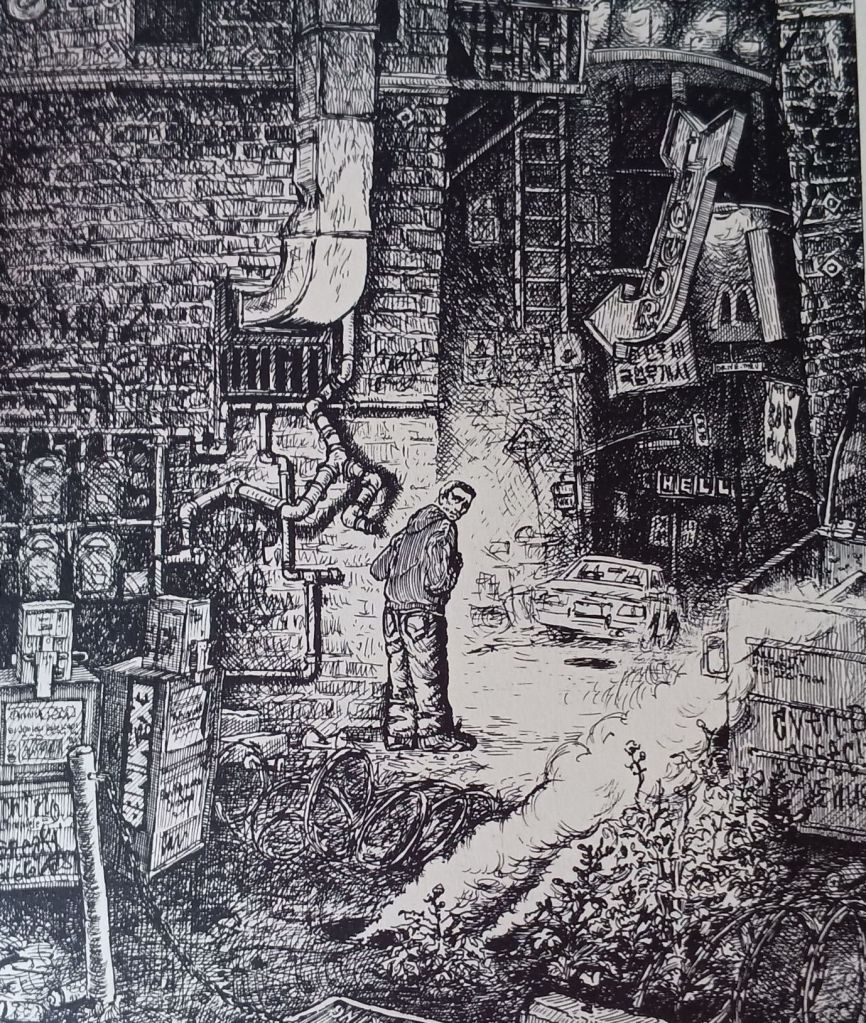

Sandown Birk and Marcus Sanders, whose Dante figure references Doré’s do not take the ‘selva obscura’ literally as a ‘dark wood’ but find their Dante leaning against the wall of tenement backs, being as much garbage as that collected around him. At the back is the portal to Hell abd, guess what, it has a Ronald MacDonalds:

Well, why not Dante, then? After all, you can choose a guide. He chose Virgil. I suppose that choice was because it was to Vergil’s powers as epic and allegoric poet to which he aspired. That’s rather refreshing in a world where mentors are supposed to be like Lord Alan Sugar, or worse, Elon Musk.

Botticelli certainly shows Vergil able to point the path in a way that Dante and the rest of us miss when we have already taken ‘a few wrong turns’.

William Blake’s Vergil seems a bit sterner: Dante is still choosing the opposite way to he, even at the portal to Hell.

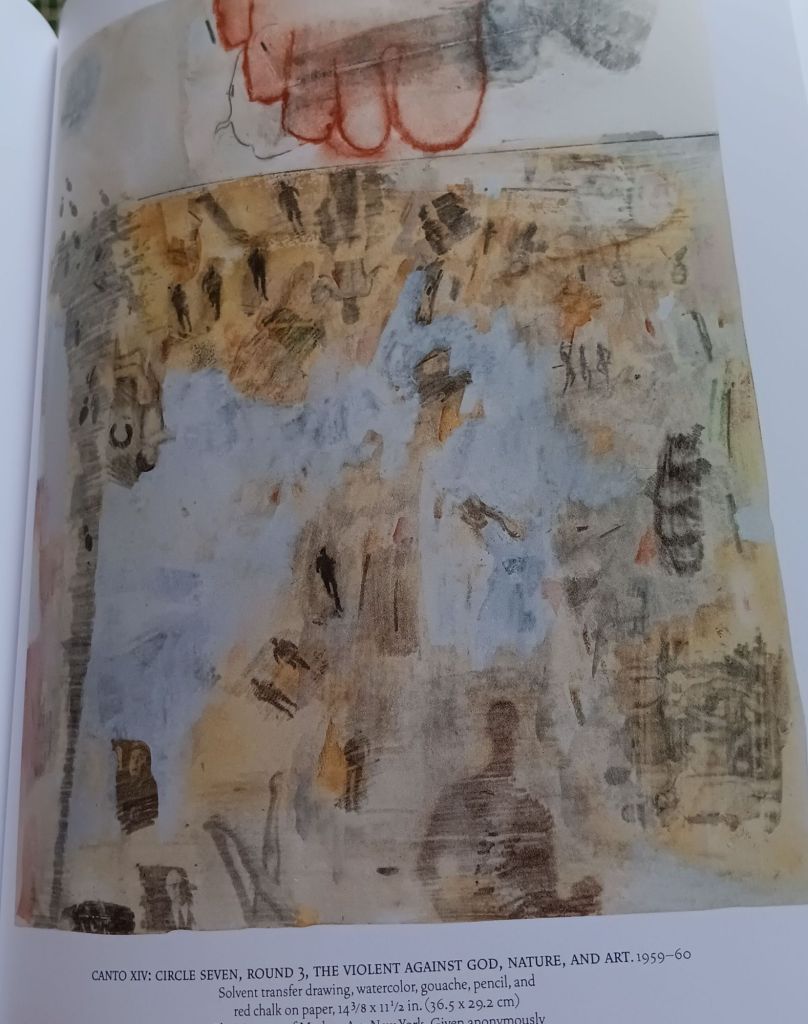

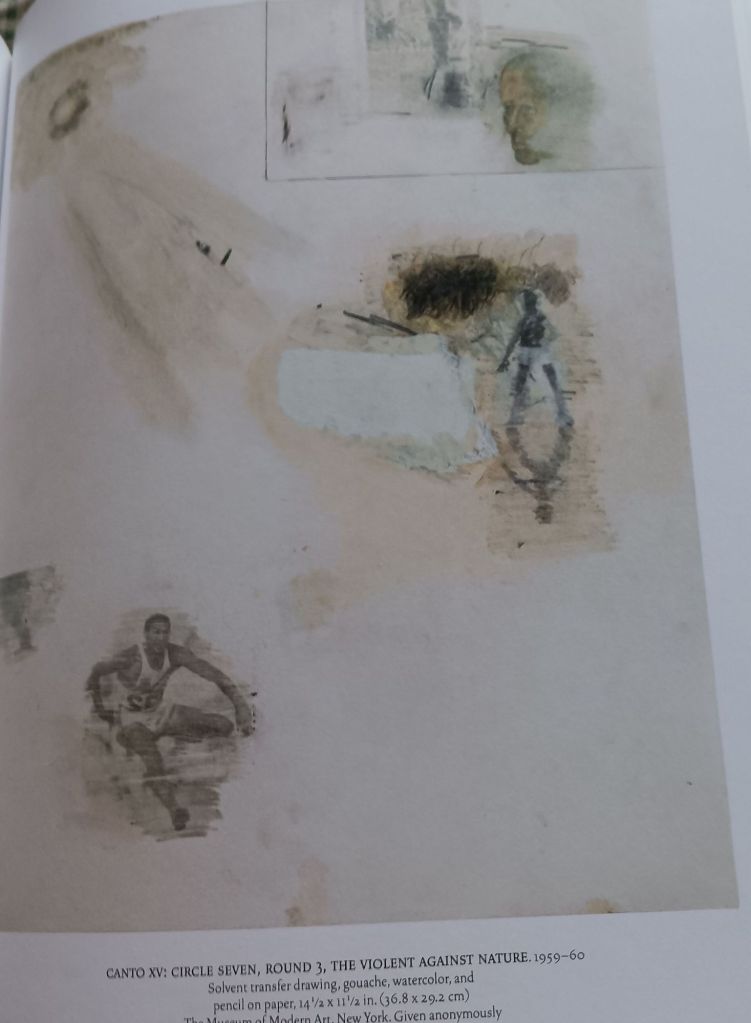

But could he have known as his journey starts the complications of his route? I suppose so, though even the path God sets the blessed seems set with traps if you happen to be quite unhappy with always taking the ‘straight’ and not the queer way. Robert Rauschenberg certainly felt that the difficulties of his own life, set by its lack of public recognition and firm display, as in his partnerships with Cy Twombly. and even that with Jasper Johns. His illustration of the fate of queer men in Dante – destined forever run across the sands, forever in a barren channel, because those sands are too hot for softness and delicacy of the sole [of a foot], to say nothing of a queer soul like Dante’s old teacher, Brunetto Latini, who full of pagan reverence for the male body, still refuses to accept Dante’s love and reverence in bodily form but points him on to a heavenly goal lest he have to run on hot soles forever.

These themes run across Rauschenberg’s illustrations for both Cantos XIV [the suicides] & XV [the Sodomites] for queer men of Rauschenberg’s time understood, alas, the link between these ‘sins’. The illustration for XIV is filled with the imprint of unresting feet:

The poets ( Robin Coste Lewis and Kevin Young), who worked with Rauschenberg, express the plight of the sodomites [in XV] thus:

The Dark Road pointing us toward the needle's eye.

Both sides hunger but never reach the grass.

We were all clerks of the one same crime -

Defiled Earth.

If you have any longing, run!

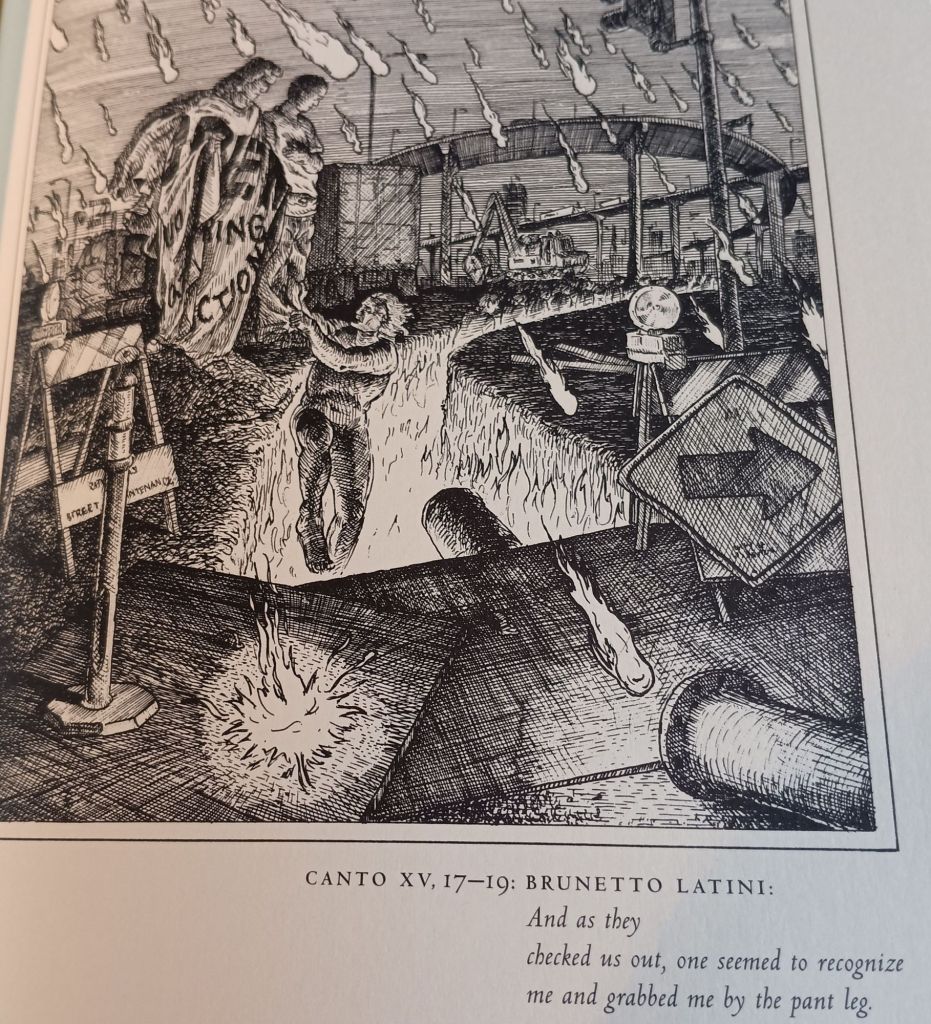

Brunetto Latini, with the gaze of a queer eye on all men, as some men think, in Birk and Sanders version, in Dante’s words sought to ‘check us out’, the us being he and Virgil, as queer men might and Latini grabs Dante by the ‘pant leg’.

So far and so various, then in my plan to be Dante. Be careful. The Christian Church grabs all of the attention once we get to Paradise. Giovanni di Paulo emphasises in an illumination, shared by Martin Kemp in his 2021 book Visions of Heaven, the path to the light of rest as thoroughly heterosexual as the witness God as the First Mover of the sunlike Universe. In the end, this hero just has to come to God through a heteronormative kind of guidance – now Latini has long gone and even pagan Virgil, however moral a guide, could not cross to Paradise.

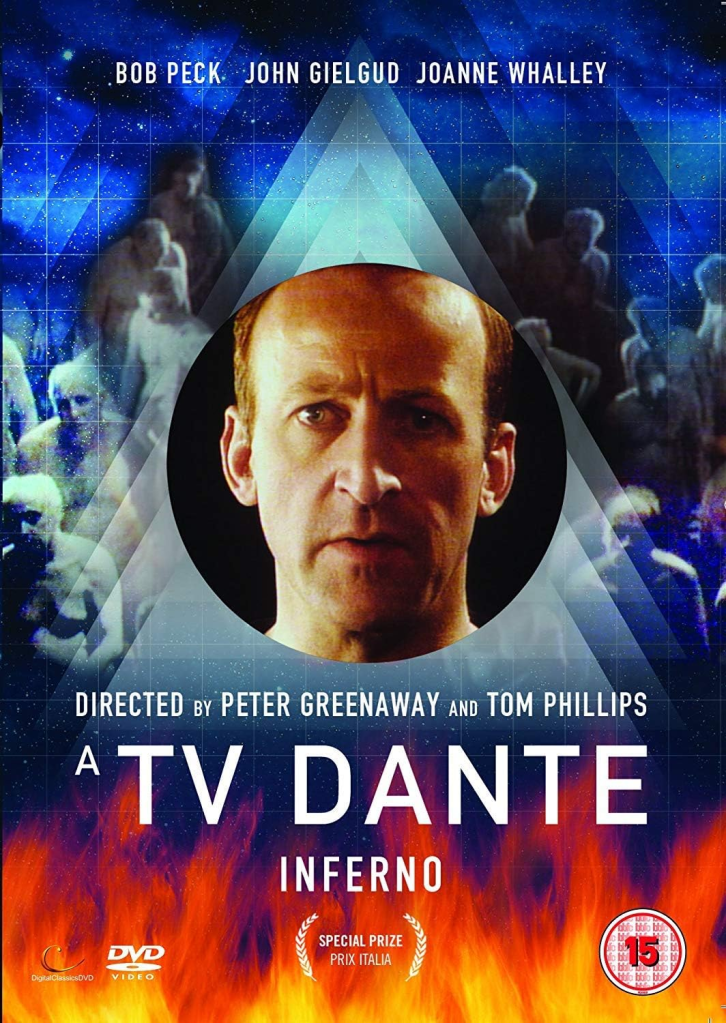

Maybe then I will stop being Dante at the end of the Inferno, for Hell has all the best stories in this poem, I think. And then again, Bob Peck was wonderful in the film version of the hero in Peter Greenaway’s TV-Dante and that didn’t even get beyond Canto 8 of the Inferno: stopping well before any of us get to Dante’s undifferentiated, and un-differentiating, Paradise of Diversities Lost.

And Bob Peck / Dante had a queer Virgil (John Gielgud, still smarting from victimisation over a cottaging incident). So, yes! Dante! But I want Ian McKellen as Virgil and Latini.

No neutrality ever in my Dante for, for even bisexuals must commit in the moment of their passion:

All for now

With love

Steven xxxxxx