‘There is always too much and too little said in any story of desire’. [1] Simon Goldhill is an exquisite historian as well as scholar of Greek drama, as his book on the Benson family deeply illustrates (see my blog on this at this link). As works they they therefore satisfy without commentary – for commentary is to add ‘too much’ and even the say ‘too little’. His work reads best in its resonances and their reflections on their necessary omissions. In this book the major omission, noticeable because there in the story’s narrative cracks, is the history as it is lived by Goldhill himself – a queer Fellow in the same community here telling its story of transitions through history almost up to this present absence. But it is necessary not to gild the lily.

This book insists that any history of the same community can start and stop at similar junctures in history and yet tell very different stories. The way Goldhill does this is to tell three stories – one about people captured in the wake of the ‘discovery’ of a term to describe them, the term ‘homosexual’ used as if to name a pathology, the story of a politics of governance (of self and communities – even of nations and the globe in the contribution of Goldswothy Lowes Dickinson – who was to E.M. Forster and others ‘Goldie’ – and the story of art as a reflection of all this, ending finally with the burial of the term under its weight of baggage of medicalisation, exclusivity and special pleading for a way of being separated from the world in which others live in diversities – mostly unsafely and without defence against hostility.

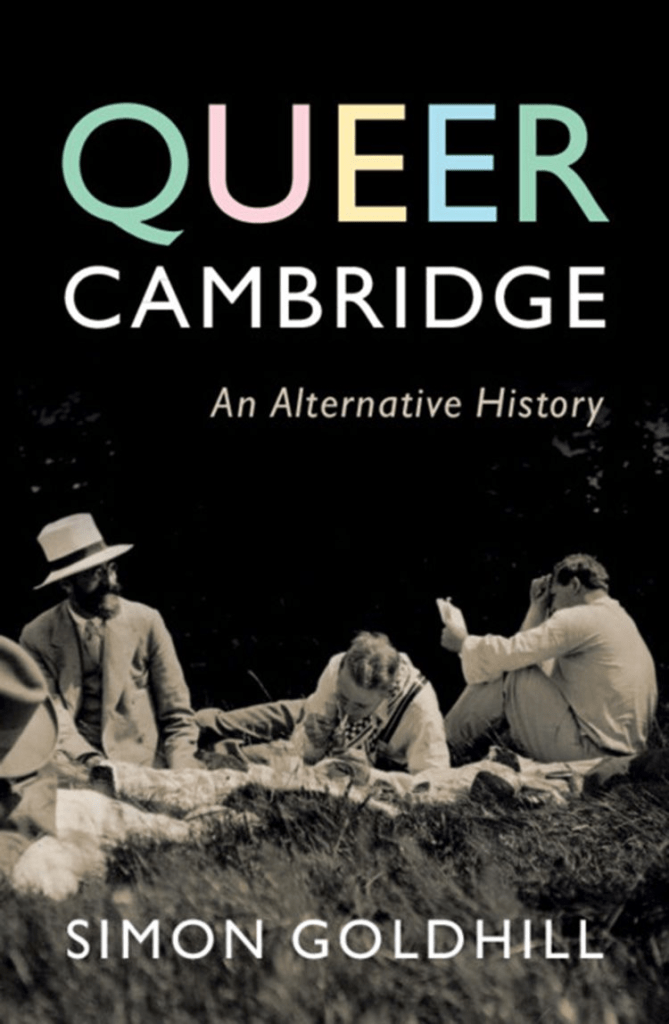

In yesterday’s blog I said: ‘I have just read Simon Goldhill’s wonderful book published this year (2025) Queer Cambridge: An Alternative History and will, when I am able and have reflected a little more, blog on it’. This ‘blog’ is therefore a retraction of that intention, for the result of my reflection is that this book tells its own story and needs no more said, though there be, of course, much that can be said – especially on the ways it articulates queer politics and queer art inn a world where alternatives to the main sad and bad narrative have waned. In a sense this is a result of the most rapacious of the book’ characters: John Maynard Keynes,

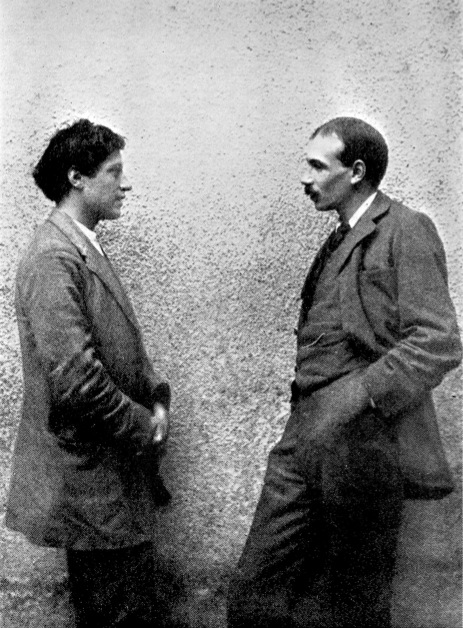

Keynes opened up the narrative of growth and continual wasteful use of precious resources at all costs as an alternative to what was to become is main enemy outside of socialism and Marxism (against which Keynes mainly pitched himself) neoliberalism and the theory of aggressive individualism as a way forward in itself. But how different was Keynesianism. Rare flowers like Duncan Grant never saw through his friend Keynes. Lytton Strachey, as cited in this book, likened Keynes as a consumer of the stock of young men to a bullish bidder on the stock market: Goldhill summarises Keynes elegantly as identifying as a political ‘homosexual’ only in ‘resistance to its criminality’, adding:

… – a resistance which was, in reality, a pursuit of satisfaction rather than a reasoned position about social oppression or ethical norms. for Keynes, one suspects, it was more a case of making sure that his sexual demands created supply. [2]

What a brilliant perception that is, It almost describes the ‘changed Labour’ position of the present Government, excluding its sexual politics if it has any but maintaining the status quo. That applies too to the reformulation of the biography of Rupert Brooke as a sexual being and a resister of humane principle in the book too – a brilliant summary of current thinking on that sad Pagan.

Yet how are we to recreate the sense of responsibility in queer politics of a Goldie, and for our times – where the survival of the globe is the issue? I resist giving in and thinking that the perspective given by diversity cannot be one that renews but that just consumes what is and too much of it. But on this you definitely can say too much and still say, and do, too little.

This is a book that is a joy. Thus end my non-blog.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

____________________________________________

[1] Simon Goldhill (2025: 21) Queer Cambridge: An Alternative History Cambridge University Press

[2] ibid: 124f.

One thought on “‘There is always too much and too little said in any story of desire’. A blog that won’t be written on a book that just needs to be read and reflected upon.”