A distant memory of a distant Peter Avery: “Between my vice and my religion, I find myself continually on my knees” A straightened memory of a queer Fellow.

I have just read Simon Goldhill’s wonderful book published this year (2025) Queer Cambridge: An Alternative History and will, when I am able and have reflected a little more, blog on it. But as I came to the end I came across a memoir of life of Peter William Avery OBE (15 May 1923 – 6 October 2008) near the end of the book, a life which Goldhill sees as one of the reactions to the end-phases of a glorious period in which the lives of famous queer men dominated King’s College but particularly the Gibbs Building and particularly H-staircase of that building – the one nearest to Kings College Chapel.

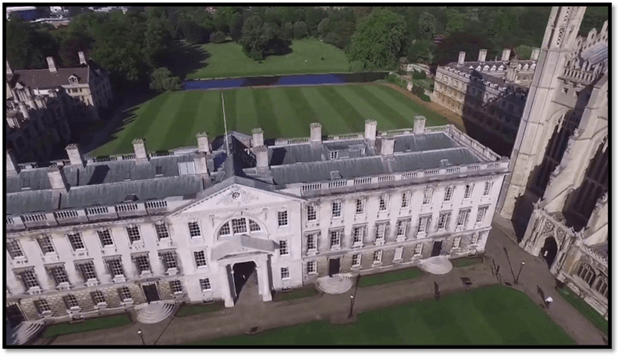

Still from Thomann-Hanry® at Gibbs’ Building, King’s College Cambridge

The men Goldhill speaks of progressively moved from their self-conscious hey-day at the end of the Victorian era to the very beginning of our current millennium were central because their rise and fall as a group matched that of the term they gradually embraced as a self-descriptive term until its own usefulness to queer people was outlived – the pathological label ‘homosexual’- for it rationalised secrecy and reserve about ones sexual being, whilst normalising it, at least at the margins of a comprehensive social-psychology. These men dominated the intellectual life of the college in many disciplines – the best known being economics and literary study. When the association of queer men and this illustrious academic institution, once the goal of students from Eton School only, began to be buried, Avery, according to Goldhill, used the last remnants of privilege his fellowship accorded him to live a life of almost open ‘self-expression’ and ‘challenge to heteronormativity’.[1] He did it with flair that only the barrier walls of a ruling-class institution between him and scandal. Goldhill records his use of rent-boys and male students as prey to his fascination with men who have sex with men, both as participant certainly with the rent boys or onlooker with what Goldhill calls ‘wilful transgressiveness’. It is from these open behaviours (within the safe institutional enclosure of King’s that Peter referred to his Catholicism and ‘homosexual practice’ as the dilemma in my title: : “Between my vice and my religion, I find myself continually on my knees”. Summarising his life of reading he moreover said that ‘that the only thing I read at night is tattoooos (sic.)’. [2]

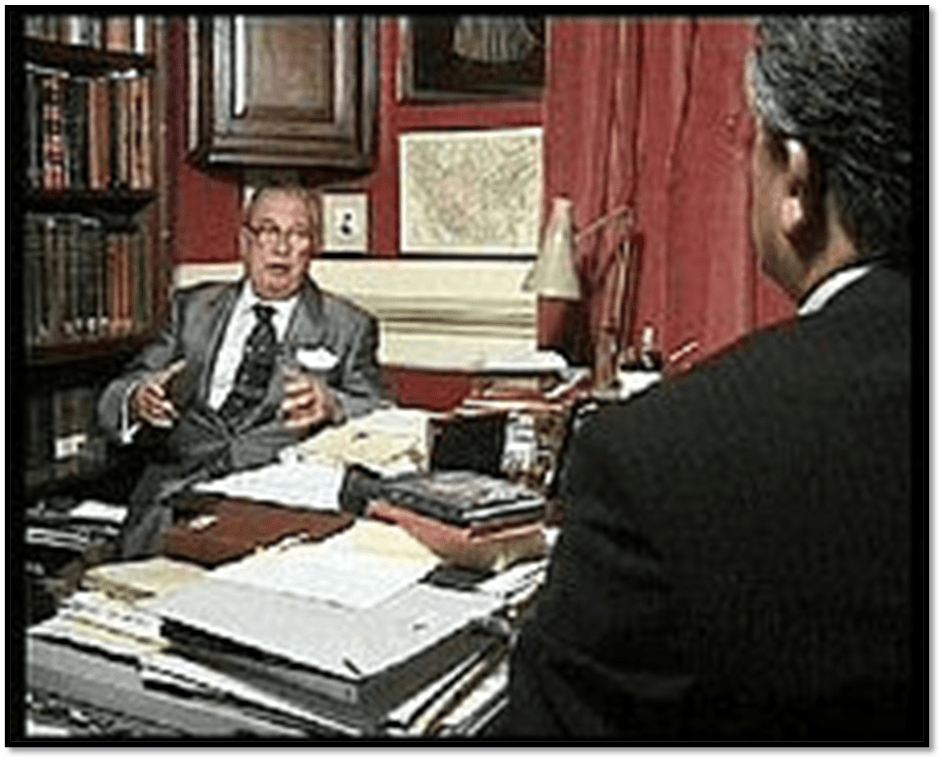

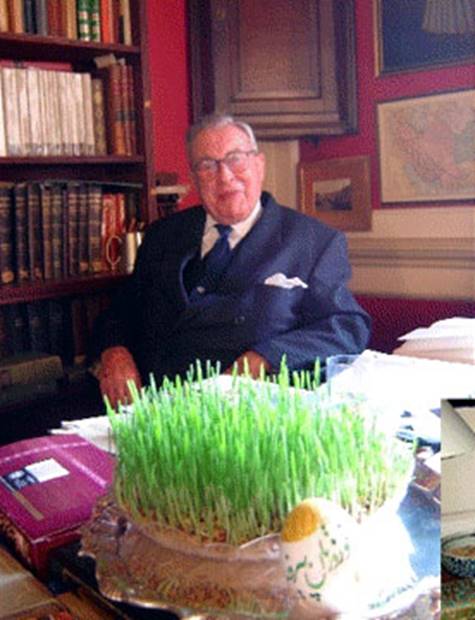

Peter Avery, eminent British scholar of Persian and a Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge.

This blog is really only about the discomfort this reading has brought me. From a working-class Northern family I hid my queer sexuality well into the period at university (at University College London) than with its English Department presided over by Professor Frank Kermode. The latter was appointed to a Chair in English at Kings College Cambridge in my final year at UCL and my tutors suggested I seek to work with him on the foolish enterprise of a PhD., foolish because my interests were never strict enough to be described as ‘academic’ or ‘scholarly’for these were not parts of the culture that made me educationally or socially what I am. Yet to Kings I went.

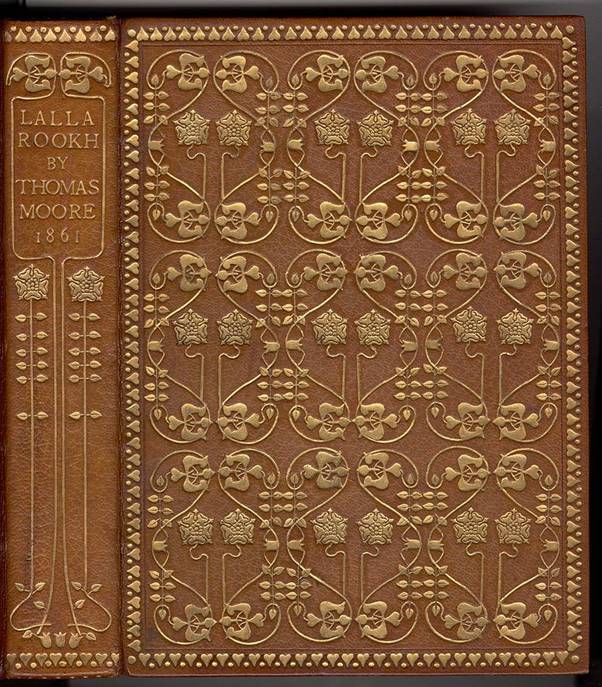

In the days when I thought I would finish a PhD on Browning I was working on Browning’s plays Paracelsus and The Return of the Druzes, and Kermode expressing some amazement that anyone might want thus to concentrate said he felt I needed input from a scholar of the wisdom of Persia. Hence, he arranged for me to see Peter Avery. I thought then that neither Avery nor I ever quite knew why we were brought together. He was singularly uninterested in me – being no male beauty nor currently working-class enough to be tattooed. Nevertheless he saw me, was amazed at my ignorance of Byron’s Orientalism and ‘Tommy’ (as he referred to Thomas Moore) and advised me to read Lalla Rookh.

He said I was welcome to return at any time. Just knock on his door unless he was ‘sporting his oak’ (he explained to me that this meant the closure of the outer door, on the staircase lobby, of his apartment. I did once return in a drunken state – for it was during this time I became first pathologically depressed, but the oak was very definitely ‘sported’. Otherwise, I didn’t want to. There was something too brash for me about him, something recalled in Goldhill’s description of his ‘plummy voice, although I little knew that he was originally a grammar school boy whose position depended entirely on his scholarship in Persian and Iranian literature. Nevertheless. though he took little interest in me, as already said, he dis point me to a gay night-club that I might attend and meet him there, outside Cambridge and also referred to in Goldhill.

Peter Avery in a TV interview with the Iranian journalist, Ali Akbar Abdolrashidi

When, months later I saw him there, he and I were otherwise engaged, me to a barman from Trinity College who also worked the door at the club and with whom I lived for a short time, him telling me stories of working for the Krays in clubs in the East End. I barely credit those days. I was always plastered with alcohol and mentally circling with the black ravens.

Now, as I reflect, I realise that Avery’s writing was known to me, if only from his co-translation and prefatory work in the Penguin Classics Ruba’iyat of Omar Khayyam.

But at the time I knew little of the scholarship and had no inkling of the behaviour Goldhill called ‘outrageous’. But, reflecting back now I feel somewhat hurt by Frank Kermode’s part in all this. He knew of me as queer, for he knew I knew his Co-Professor at UCL, Stephen Spender, and another friend lecturing there (and oft his proof-reader, as he had been then to the wondrous The Genesis of Secrecy, about narrative theory), Keith, who ‘took me’ on as queer lecturers did then. See Simon Gray’s Butley for a taste of all this. Keith and his husband told me this play was based on both of them – excepting the heterosexual cover bits of Butley’s character. As I read Goldhill, the perception came clearly to me that Kermode had set me up with Avery – after all the kind of network understanding of the academic queer community held by straight’ academics was precisely that of a kind of exchange of favours in the interests of being ‘recognised’. None of it was clear to me them but equally none of it had any consequences for me

Goldhill tells us that Avery offered care and support, putting him to bed when frail, to fellow Fellow of the college Edwin Morgan (E.M.) Forster. That is beautiful but not the tone of the man I briefly met. The man I met is much nearer to the description from Goldhill given below – a man who took advantage of obscene privilege and did not much care about queer men outside the college environment except in those ordered in like the rent boys Goldhill mentions. But what I do remember was that Avery was dismissive of any other but sexualised experience amongst queer men and that reduced the scope of liberation to which I and many others, not in privileged classes or privileged by institutional power, had available to me then and for too long later. That applies to all of the young struggling queer men I knew in the period. Not all of the latter were victims but some were. I count myself then as that but do not count myself thus now. Goldhill is brilliant on the privilege of Avery. It was won by merit but used as if merit no longer mattered, only the security offered by a two-faced status quo that looked after its own (those withing the ring of its institutional defences) and scapegoated the rest.

Ibid: 235

So now I no longer feel as sore at being set up by Frank Kermode, if indeed he did (which I will never know and anyway barely care about now) . I left Cambridge to go to Leicester University to continue my studies where I met my present husband – and still didn’t finish that PhD. on Browning, though I went into academic teaching for about 11 years (good years but not because of academic contribution I made). I was, I think, a good teacher.

Indeed I am glad I lived through those pre Me-too years and the hard leaning they involved, for naked power doesn’t change its spots. I think it just finds it more difficult to survive in the domain of sexual relations in academia – though it exerts itself in other kinds of unfairness, lack of care for the things it is allowed to handle (subjects and learners), and abuse. And Strangely I must have been unattractive enough to be safe (Phew!). I was at one Kings College Event introduced to Noel Annan (also in Goldhill’s book) who had lectured to us at UCL on the Uranian poets. He said: ‘Have I met you before?’ I mentioned that lecture. “Have you met my daughter?”, he said, whilst walking off, landing me with her to our common embarrassment. LOL!

We need to be grateful for memories that didn’t end us!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Simon Goldhill (2025: 237) Queer Cambridge: An Alternative History Cambridge University Press

[2] Ibid: 234

One thought on “A distant memory of a distant Peter Avery: “Between my vice and my religion, I find myself continually on my knees.” A ‘straightened’ memory of a queer Fellow.”