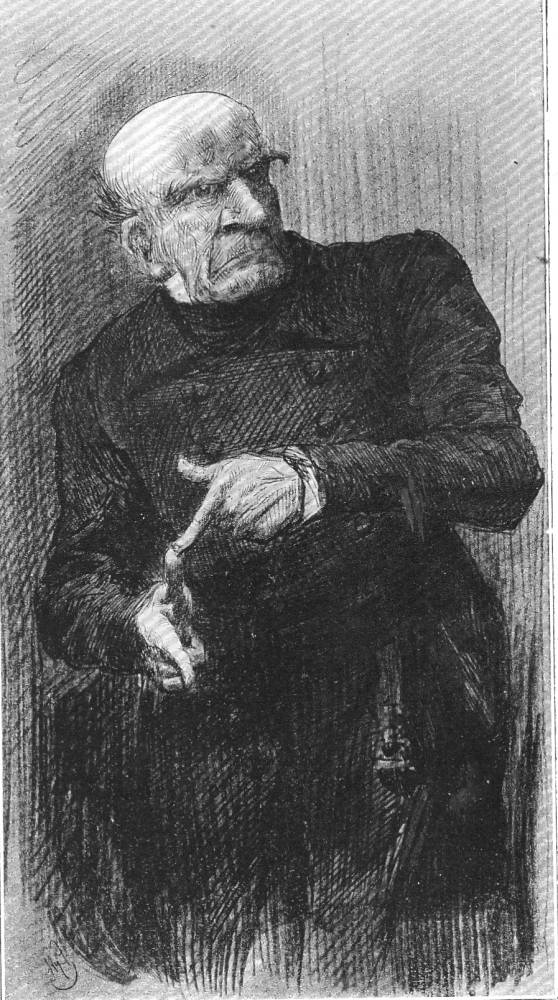

Thomas Gradgrind, the teacher in Dickens’ ‘Hard Times’ , in the depiction made by Harry Furniss as frontispiece to the novel. A man who uses his fingers to point – did Furniss intend to capture the early etymology of the word ‘teach’.

‘Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!’

The scene was a plain, bare, monotonous vault of a school-room, and the speaker’s square forefinger emphasised his observations by underscoring every sentence with a line on the schoolmaster’s sleeve. The emphasis was helped by the speaker’s square wall of a forehead, which had his eyebrows for its base, while his eyes found commodious cellarage in two dark caves, overshadowed by the wall. The emphasis was helped by the speaker’s mouth, which was wide, thin, and hard set. The emphasis was helped by the speaker’s voice, which was inflexible, dry, and dictatorial. The emphasis was helped by the speaker’s hair, which bristled on the skirts of his bald head, a plantation of firs to keep the wind from its shining surface, all covered with knobs, like the crust of a plum pie, as if the head had scarcely warehouse-room for the hard facts stored inside. The speaker’s obstinate carriage, square coat, square legs, square shoulders,—nay, his very neckcloth, trained to take him by the throat with an unaccommodating grasp, like a stubborn fact, as it was,—all helped the emphasis.

The word teacher does have an interesting etymology that might not have worried Thomas Gradgrind, the very model of a BAD teacher in Charles Dickens’ novel Hard Times. Dickens was a man of curious learning and I suspect he knew, as etymology.com points out, that the equivalent term to our term ‘teacher’ was in the early 14th century used ‘in a sense of “index finger” (early 14c.). By c. 1400 as “animal trainer”. Both meanings point to Gradgrind – a man who sees his role as the training out of children their wildness, and their subjective view of a world he wants to reduce to utilitarian (usable) FACT.

Everything about Gradgrind is regulated and hence ‘a square wall’ in the passage above, the ‘wall’ of the head as a mere industrial warehouse for storage storehouse, and choked of life, just like his neck by his neckcloth, that is ‘trained to take him by the throat’ chokes him. All learners, even oneself are just ‘stubborn facts’ you see, reluctant to undergo magical metamorphosis in the fancy. Yet Dickens uses his fancy – in the mixed imagery of the plantation of firs and the weirdly adjacent one of the crust of a plum pie to sneak a giggle at Gradgrind, without him knowing this is happening (as learners are wont to do of bad -and good – teachers).

Above you see Gradgrind’s teacherly philosophy unfurled from the first chapter of the novel. In Chapter 2, the relevance of an index finger to teaching is seen its applied aspect:

‘Girl number twenty,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, squarely pointing with his square forefinger, ‘I don’t know that girl. Who is that girl?’

‘Sissy Jupe, sir,’ explained number twenty, blushing, standing up, and curtseying.

‘Sissy is not a name,’ said Mr. Gradgrind. ‘Don’t call yourself Sissy. Call yourself Cecilia.’

‘It’s father as calls me Sissy, sir,’ returned the young girl in a trembling voice, and with another curtsey.

‘Then he has no business to do it,’ said Mr. Gradgrind. ‘Tell him he mustn’t. Cecilia Jupe. Let me see. What is your father?’

‘He belongs to the horse-riding, if you please, sir.’

Mr. Gradgrind frowned, and waved off the objectionable calling with his hand. (1)

Sissy Jupe with her pet name and faulty grammar, cannot be seen or known by virtue of a teacher’s finger attempting to recast her into hard square iron ingots using the raw material of the roundness of her fleshly being. She willed. Ot be tooled into shape by a ‘square forefinger’, any more in fact than other realities in the world can be transformed into quantifiable facts like the ‘number twenty learner’ she represents to a dry mind such as Gradgrind ‘s.

However, the word teacher as it came to be used in the mid fourteenth century, and with authority from Old English, might be used in a different way than to point imperiously. It may show a child, or other learner, the ways that will take them forward into the world. The verb ‘teach (v.) is derived thus:

Middle English tēchen, from Old English tæcan (past tense tæhte, past participle tæht) “to show (transitive), point out, declare; demonstrate,” also “give instruction, train, assign, direct; warn; persuade.”

This is reconstructed to be from Proto-Germanic *taikijan “to show”…

The idea of pointing need not be oppressive when it guides someone who needs and wants (preferably both) some direction. This idea would not surprise teachers trained in the post Montessori and Froebel ideologies of teaching, for good teachers of these methods do not tell or even primarily model what is to be learned to but do those either or both of those things only in as much as they facilitate a learner to learn for themselves. And to learn for yourself requires that your fanciful groping for ways to seek multiple answers to a pressing problem has to be respected, including the errors that accompany a trial of your learning. A good teacher travels on this route with you; engagingly constructively with woolly error with its fuzzy boundaries as well as with precise and concise answers – for otherwise a person never learns to think laterally as well as vertically. A good teacher opens up the process of learning.

In truth, any kind of teaching – whether in person or remote, through voice and/or text (textbooks or websites in distance learning, for instance) – should do this. That is why I think the use of multiple choice questions which bind us to one answer is so anti-educational if used as a path to truth. It, like Gradgrind, tries to force us to think that all answers are singular and not driven by other factors and contingent issues.

Recently I was taught something about the interpretation of history by George Mackay Brown (GMB) in two short, and relatively insignificant texts he left behind. Often asked for Forewords and Prefaces to transitory publications, he never stopped pointing to larger ways in which meanings come into being in history.

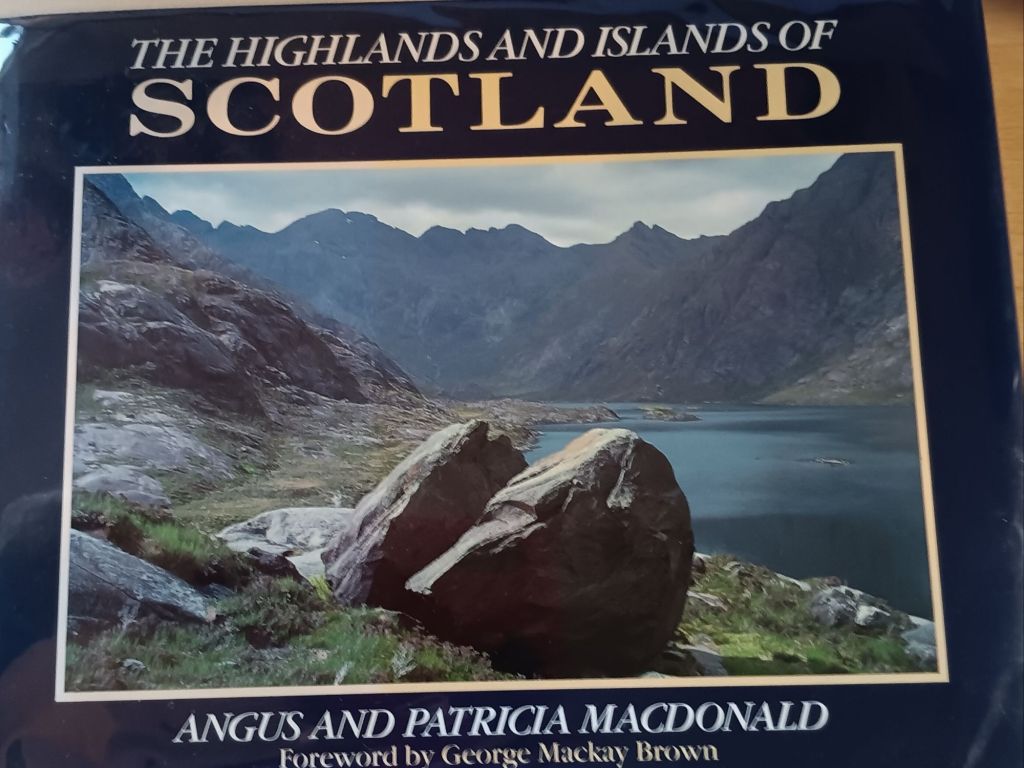

To a beautiful book of photographs by Patricia Macdonald, with text by her husband, Patrick, in 1991, and called The Highlands and Islands of Scotland, he contributed a tight little introduction.

In that brief introduction to this book, Mackay Brown shows how people learn through fancy somethings that have potential value, if not necessarily utility, for the future when the hard fact may have none. He argues that the Scottish Highlands and Islands were not a ‘symbol of beauty and high romance’ except by the experience of oppression (the English and the Lowlands bourgeoisie) and defeat bybtje people in them. The English tasted victory at Glencoe but made it final at Culloden in 1746. Gaelic peoples, he continues , ‘have the gift of transmuting suffering and defeat into beauty’. They did so by myth-making and folk-story, such that ‘the wild lonely places meant freedom and delight for the human spirit that was, by the beginning of the nineteenth-century, beginning to chafe at the ugliness of industrialisation and grime and unwholesomeness of the new cities’.

As GMB says in this text too, the transformation of perceived landscape into emotions of relief and pressure aid you to survive in a wild place. What is arduous and difficult to cross you perceive as beauty and freedom (for freedom has its pains as well as pleasures). These ideas had a lot to do with European Romanticism, which looked for both beauty and liberty in wild glens and sea caves, like those of Fingal on the coast of Mull. And it found it too in a mythical past, with its own wild stories like those in the Orkneyinga Saga. He even quotes a poem from that, in his version, that he uses in Vinland as the work of one of his characters – and this in an ephemeral publication in a short Forewordin a travel book. His point was that everything you say or write (however ephemeral is its circumstance) should teach someone something. He ends the introduction not with a backward-leaning adoration of Orkney and Highland culture as resistant to change but adoration enhanced and made more free by change – praising the multiculturalism and ‘racial admixtures’ as a new norm, even in Stromness, and one that leans out beyond thoses norms. That is teaching.

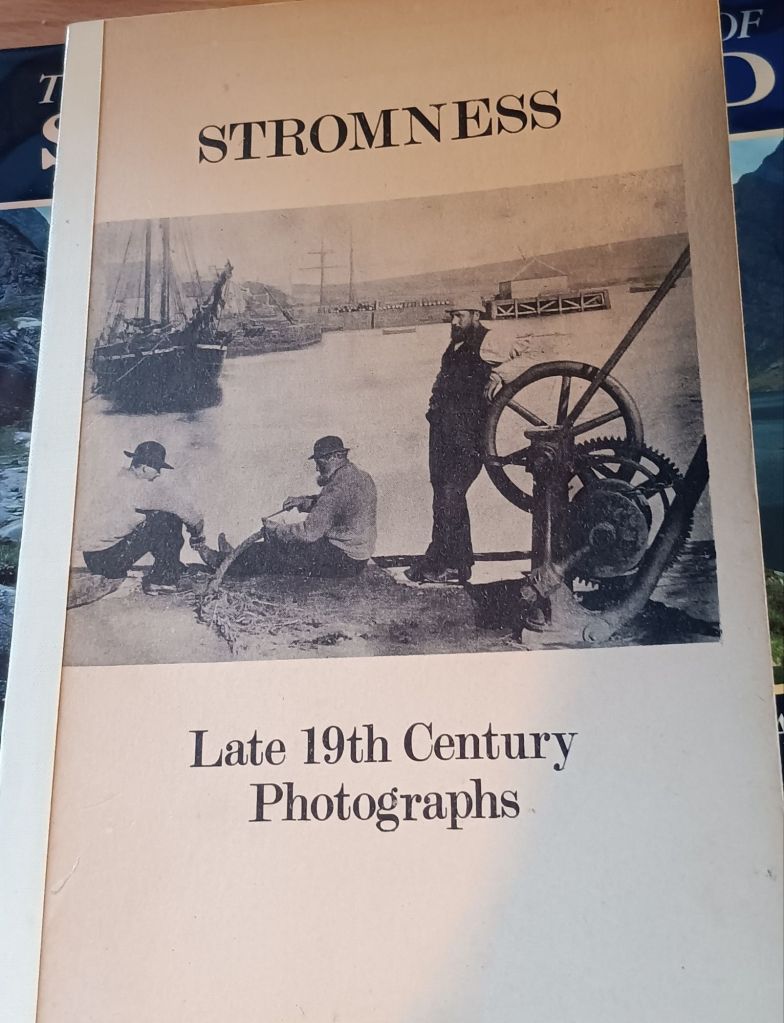

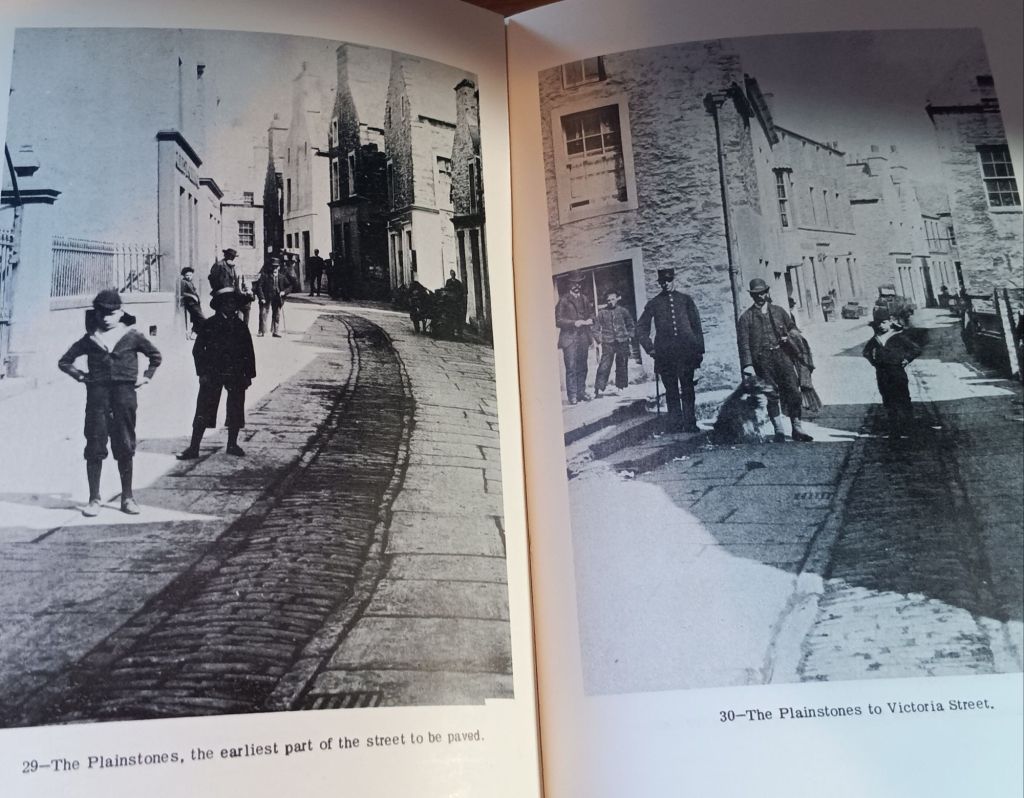

To be sure of that, consider an even more ephemeral publication in my book collection. It is a book of poorly bound reproductions of photographs of late nineteenth century Stromness (the place he liked to call by its older name, Hamnavoe).

This book of pictures is illustrated by his texts – prose and poems – rather than the other way around, because GMB knows we must learn to see this photograph art and find it beautiful. Victorian Stromness is not a place of lonely and wild beauty that is an escape from capitalist levers productive of ‘the ugliness of industrialisation and grime and unwholesomeness of the new cities’. At the time, Stromness must have looked to islanders looking back to the past of rural and marine cultured Hamnavoe exactly like that ugly space. The antique look of thus ephemeral pamphlet could even be referenced in order to see this book as backwards looking and regressive.

I think the handwriting bottom left is GMB, with that moniker [not shown in the photograph].

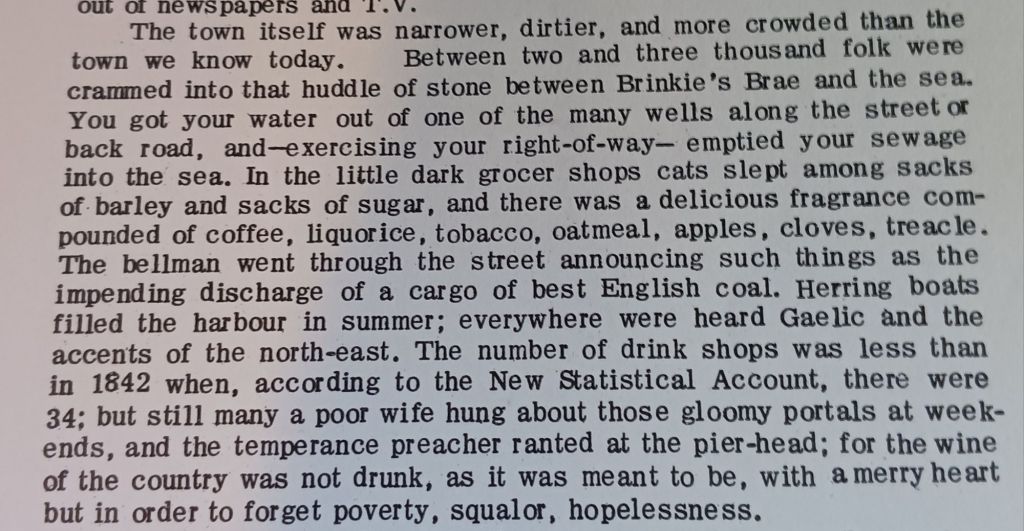

The word-picture GMB draws in his ‘Introduction’ to the book shows ugliness and degradation in the Victorian City Stromness, quite unlike today – but the burden of his writing is that these realities too are a ‘ballad’: they can contribute to the myth-making that highlights people (even in the mass) as the source of future freedom and beauty as a breathing community.. Read this and weep – but learn as you weep! .

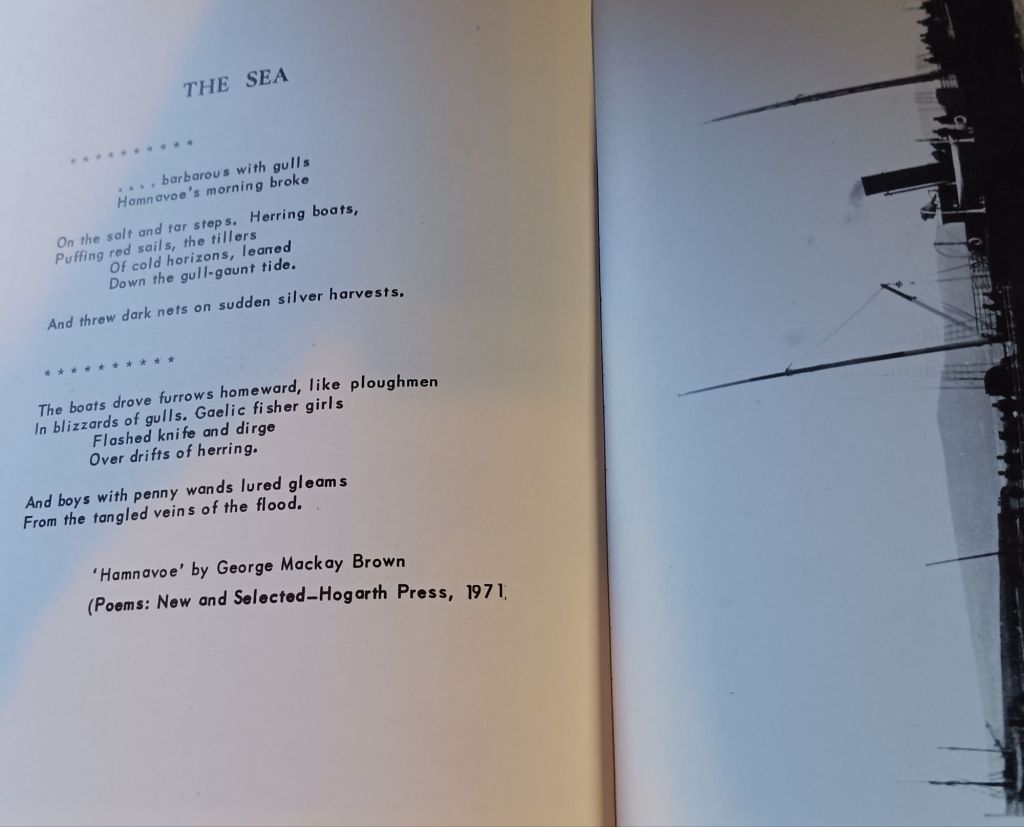

Towards the end of the whole book is this poem excerpted (from Hamnavoe – his song of old Stromness well before the Victorians). The poem is set against a picture of a modern steamer transport ferry:the very opposite of the medieval craft in the poem.

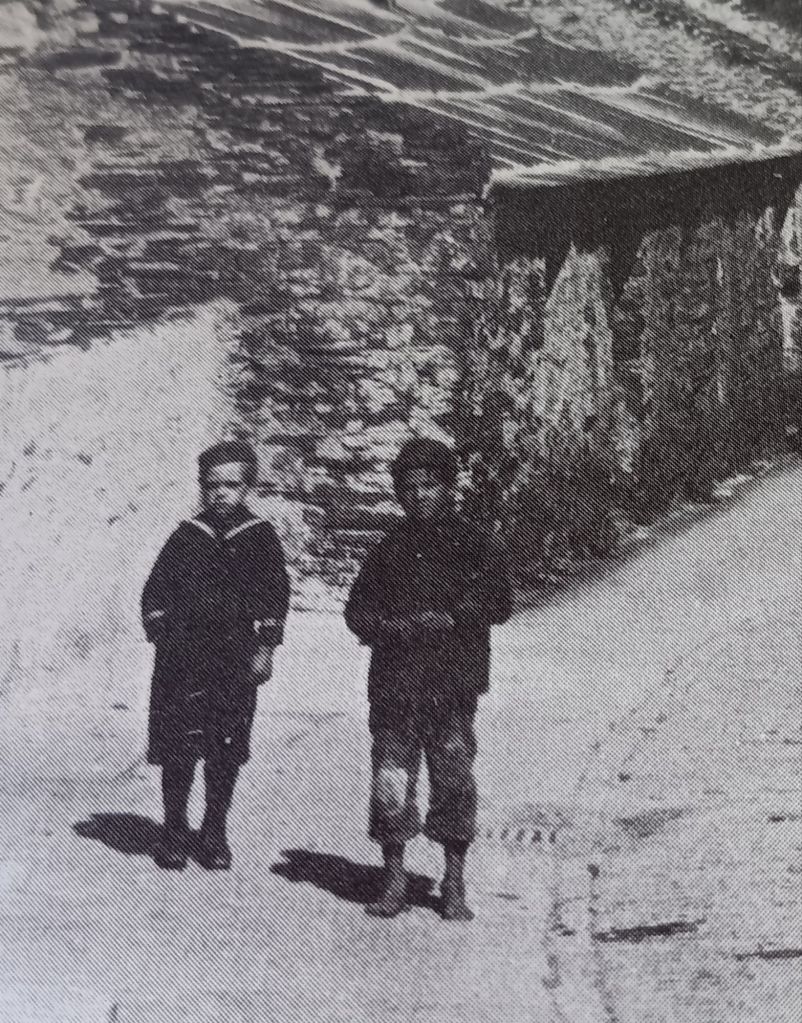

The people of old Hamnavoe knew then as much of the barbarity involved in their labour as now but were beautiful in the dignity of their survival against the odds. He leaves us to learn from the pictures the lesson of the huge contrasts of wealth and poverty in Victorian Stromness. It takes time to notice the different markers of wealth and poverty below – though bare feet in children is a giveaway.

And then look at those well-shod and educated adults and children in the bourgeois town near the school, with its new modern paving.

The point is that we may lose the ability to look and find such signs without being guided and gently pointed to them as GMB does. This may be because, as GMB says, “we moderns have lost something that our grandfathers had in full measure”.

Where they had stories and legends, we have prefabricated opinions out of newspapers and TV

Read Twitter / X and you see the effect of what GMB points out in all its horror. We need art that teaches us still. Let’s hope we learn from it – for it exists.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_____________________________________________

[1] For the full text of Hard Times, see https://www.gutenberg.org/files/786/786-h/786-h.htm