A ‘secret skill’ is coolly agreed by the AI bots on the internet to be the equivalent of a ‘hidden talent’ but, even if this is a useful equivalence it hardly solves the main problem of what either these skills and talents are. The main issue here is: to whom is the skill or talent ‘secret’ or ‘hidden’ and why is it better hidden than in the open? Either ‘secret skill’ or ‘hidden talent’ can imply that the skill and talent one possesses is hidden or secret even to oneself – one has the skill but do not know it (or don’t claim to know it). The other problem is whether tne hiding or secreting involved is done by some agency and with motive

However, therein lies the rub! – for there may be advantages in saying you are speaking naturally and without forethought (‘off the top of your head’) and pretending to ignorance of any motive in doing so, when that in fact is not the case. It may be effective to pretend that an idea for instance comes from nowhere or is in response to an immediate problem, when it is in fact a predetermined behavioural plan; a means of getting something you have long worked in secret for in order to get exactly what you want. It is also useful to develop and then cultivate skills, passing them off, for instance as natural talent, which you pretend may be just born out of nothing but the instant (a ‘passing thought’) and not from an acquired skill that is born out of artifice. You might say, for instance:

‘I’ve been thinking, and I know this will sound stupid, but I just feel I have to say now it’s come to me …..’

Of course you neither think what you are saying is ‘stupid’ nor think anyone else will, but you know that the culture of your office or government department is one that dislikes the meretricious or over-educated response to problems, believing the best ideas come from natural ‘genius (that doesn’t recognise itself as such). People oft get their way using this device of pretended ignorance.

Another skill is to understand how much people like to be heard, and to performatively listen to them (with a fixed gaze and carefully inserted nods of the head) and then reflect back to them and others more influential in the audience what they say in a way that pretends to mean what they said but is in fact a strategy of proceeding ‘going forward’ (as we say these days) skewed to your interests. If people say ‘that’s a good idea!’, you say – ‘yes I always think my colleague has the best ideas, they just don’t realise it’. Thus the colleague gets the praise for the idea (and, of course, the blame when it all goes wrong for everyone else but you) and you benefit from the way you skewed it your own interests. ‘After all, you can’t help it if all you are is a good natural listener!’: you say.

Of course a hidden talent may be hidden or secret to others as well as yourself – it is on this that the last skewed example rests. It is often best to pursue your ends quietly and secretly, using talent or specific skills that you do not allow other people to see as such. Much of Machiavelli’s The Prince is about actions like that in the politics of the Italian Renaissance city states.

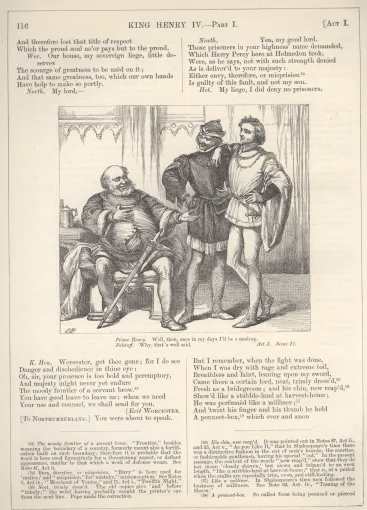

English Renaissance Drama’s stereotype Machiavels like Edmund in King Lear, or Barabbas in The Jew of Malta, hide their ambition under the shadow of their mask of ‘baseness’. The most successful is Prince Hall in the Henry IV plays by Shakespeare, who acts like a disgraceful boy in order to emerge the principled leader later:

I know you all, and will awhile uphold

The unyoked humour of your idleness.

Yet herein will I imitate the sun,

Who doth permit the base contagious clouds

To smother up his beauty from the world,

That when he please again to be himself,

Being wanted, he may be more wondered at

By breaking through the foul and ugly mists

Of vapours that did seem to strangle him.

If all the year were playing holidays,

To sport would be as tedious as to work;

But when they seldom come, they wished-for come,

And nothing pleaseth but rare accidents.

So, when this loose behaviour I throw off

And pay the debt I never promisèd,

By how much better than my word I am,

By so much shall I falsify men’s hopes;

And like bright metal on a sullen ground,

My reformation, glitt’ring o’er my fault,

Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes

Than that which hath no foil to set it off.

I’ll so offend to make offence a skill,

Redeeming time when men think least I will.

(1 Henry IV I.ii.173–195)

The whole point in Hal’s speech is to hide or secrete your talent and skill as carefully as you can, using the time to ‘know you all’, particularly those who might later stand in your way. You then present your sudden change from ‘loose behaviour’ (not as loose or natural as it looks) to virtue as if it were a miracle rather than a deeply planned strategy, and people will the more value you. Thus, you can pretend that your only skill is to offend people in order to hide that your greater skill is how to deceive and manipulate people without them knowing that this is happening. To these machinations, all of Hal’s friends are subject, and it kills Falstaff and hangs Bardolph – quite literally the latter on the field of Agincourt in Henry V.

Richard Briers as Bardolph being hanged in France.

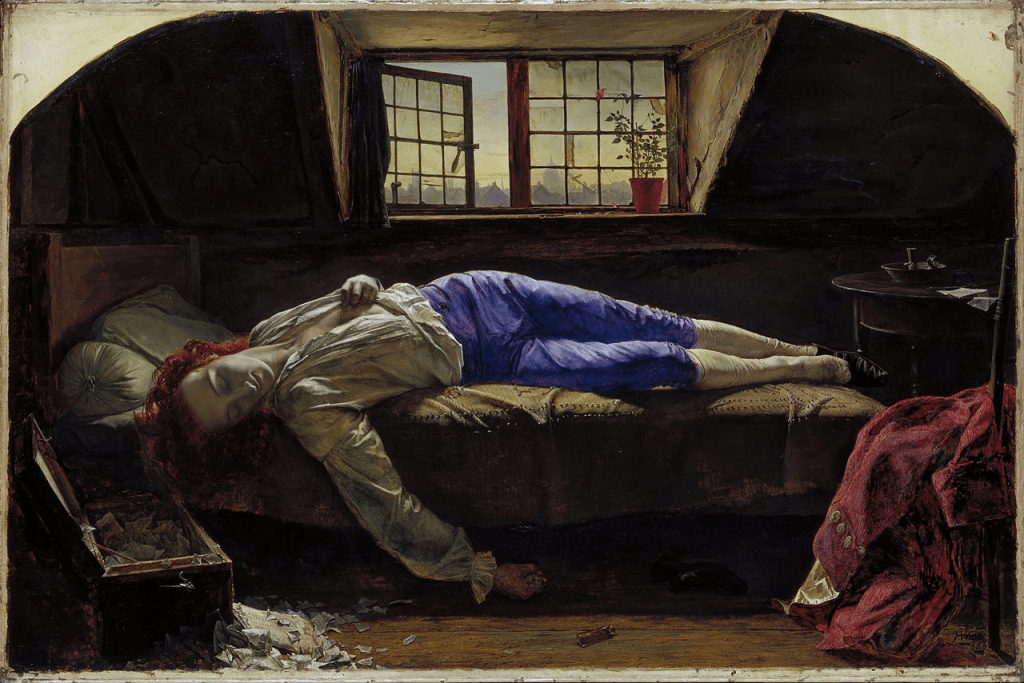

Hence, if you want to win at all costs – costs to your morality, to the good of others or to decency – make sure your most honed secret skill is your ability to maintain secrecy and to hide your motives and the talents used to achieve them. The sage Robert Browning thought that was the case even when your cause was noble. Nobody likes a boastful and self-aware talent, he thought, and a poet who has this power might be best to hide that fact. That is how he reads the life of the eighteenth century poet, Thomas Chatterton. In his Essay on Chatterton, an under-read piece, he says that any poet who is conscious of their powers as a poet knows that he they must not shout out that fact and will in fact write their first poems as if by another person. Into this trap, Chatterton fell – his supporters claimed he was too naive and young to write the medieval pastiche poems he pretended to be by a medieval poet he called Thomas Rowley, whilst his detractors merely pointed out the immorality of being an impostor and publishing poems without a right to do so, in neither case could he win respect for himself. Clearly the beautiful young poet George Meredith hummed to this theme too when he modelled for the earlier poet for the famous Death of Chatterton painting by Henry Wallis – who used the time of Meredith’s modelling act to sneak off with Meredith’s wife, prompting Meredith’s poem Modern Love.

What hidden talents were on show during this process of painting a tragedy of human talent wasted? What secret skills did Wallis use to woo Mrs Meredith? Would a better question for this prompt be:

What’s a secret skill you have that others later wish you hadn’t had?

I think a culture that is obsessed with ‘secret skills’ and ‘hidden talent’ is already a self-deceiving culture.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx