Celebrating the achievements of women through visibility: the means and the content of our celebration in Bishop Auckland Town Hall.

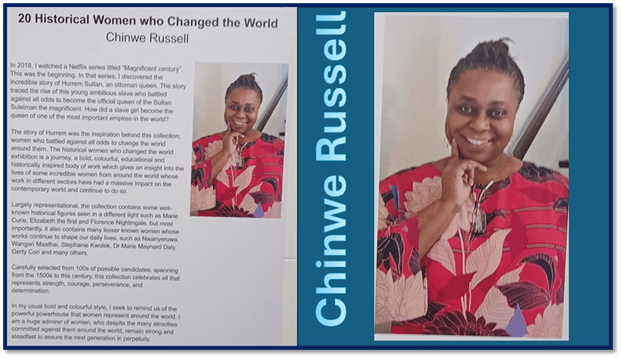

Provincial venues continually stretch themselves as media of radical representation of supposedly silenced and supposedly invisible populations. Visibility is promoted as a political object in all kinds of ‘pride’ celebrations, that insist that the fact of visibility and voice trumps the content of the semantic and active aspect of the content of what is made visible. Yet conventional pictures of achieving people who have risen above the level to which the group from which that individual achiever arose, are not themselves evidence of achievement of the group. Content matters. Chinwe Russell says this in her introduction to her pictures of individual women ‘who have changed the world’:

The point is, of course that, given the oppression of women that removes them from public visibility in public roles of power; in the realms of politics, knowledge and skills, individual women have had to fight against that oppression as well as taking on the difficulty of public roles for which preparation in ideology and specialist training was largely reserved for men. But we take for grated in all this that what matters is individual ‘strength, courage, perseverance, and determination’. Yet if that is so, why was not Margaret Thatcher selected to sit amongst that group, jostling herself to its front as she did in most groups. I speak, of course with some joy that either Russell or the curators of an exhibition in a venue where Thatcher is deemed the destroyer of local communities – male and female. Yet the reasons for lauding Thatcher can be as easily derived as the rather positive spin given to the reasons for including Elizabeth I, who is praised in the plaque alongside her picture for holding the sway of power more gently than male counterparts. That hardly however accounts for the androgynous imagery adopted by Elizabeth in her public statements that claimed that her significance was, at least in part that she was as much MAN as WOMAN. Here she speaks to the troops at Tilbury:

I know I have the body but of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

Some historians doubt the authenticity of these words but they certainly fit in with official representations of the Queen in court portraits and poetry: there feels to be much giving in to and ideology of generalised female inferiority in these words that laud traditionally male virtues in that reference to ‘the body but of a weak and feeble woman’. The issues with Elizabeth are, of course, complex, but then when it comes to creating individual achievements this is the case for all who succeed in a environment inconducive to their success im as much as they are female. Individual ‘strength, courage, perseverance, and determination’ are hardly virtues that society lacks and have in the most been the very values used to either diminish the significance of women in public social roles (if not in domestic social roles) or to shift its significance to other realms – like the role of the angel of the house so lauded by the Victorians – and analysed by Kate Millett.

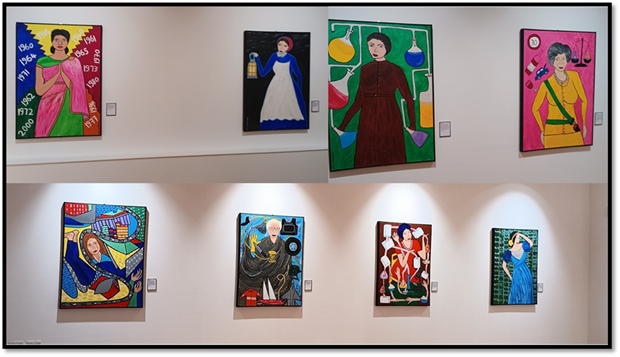

I think Chinwe Russell does address this problem in critical representation of sex / gender. Even if her words do not say so, her art rather changes the values through which we appreciate her ‘historical women’. Here is Elizabth I, for instance (centre of the collage flanked by contemporary portraits of Elizabeth, namely the ‘Armada’ and the ‘Rainbow’ portraits):

Russell uses motifs from the contemporary portraits – the eyes depicted on the clothing of the Rainbow portrait, depicting Elizabeth as all wise and able to see her own destiny, and the flanking of the naval military might related to her in the Armada portrait, but, in one sense at least, the iconography of Russell’s painting makes even greater claims for Elizabeth’s power as a woman. The orb is now the head of an enormous royal sceptre that centres her womanhood around it. Moreover, whereas in the Armada portrait. Elizabeth rests her hand on the orb represented as the orb she holds in peace, here the orb is both the globe and one focused on the particular global threat of Imperial Spain (the Americas). The dark penumbra around her, perhaps even despite the commentary next to the portrait, to me predicts the future of an Imperial West that Elizabeth view with Spain to represent – vast wealth based on control of the oceans, colonisation and slavery.

I would not however insist on that latter reading, though it would for me make the inclusion of the imperial ideology of Elizabeth I more palatable, because approached less sentimentally. The collage below shows that on the whole the iconography of the pictures may be more naïve I take it be: Barbara Castle, for instance is represented by her modest claims to fame in the governments of Harol Wilson’s Labour party – the introduction of safety belts, drink-driving and speeding, regulations in cars, without Any reference to her tough anti-union stance ion her In Place of Strife attempt at regulating the right to strike. The iconography for Florence Nightingale adds nothing to the sentimental take of the ‘Lady with the Lamp’ and women political leaders are not seen in the full complexity of their role. Nevertheless I wish I had taken more care looking at the picture on the bottom left of the collage in which the female figure is fragmented.

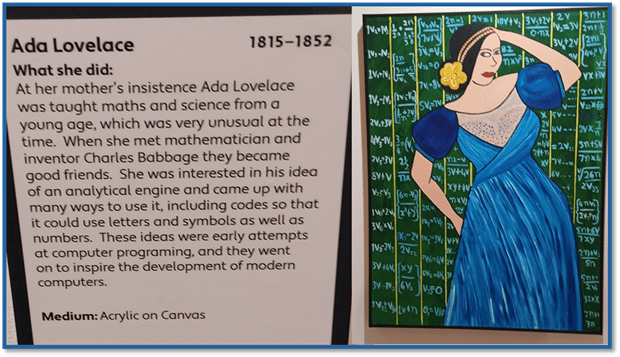

I liked the way Russell’s women are both backgrounded by their achievements, such as those of Ada Lovelace below with he extension of mathematics into symbolic coding necessary for the later growth of computer functionality, but also somehow ensuring that that the woman stands out distinct from them.

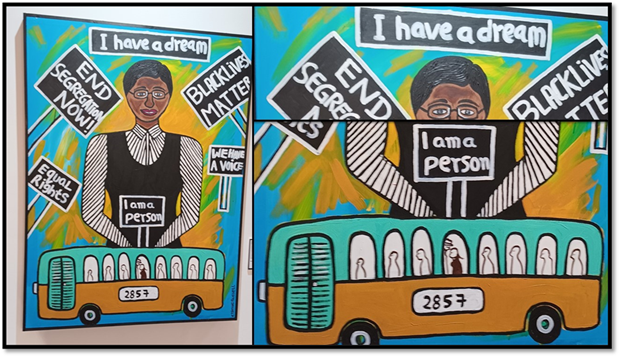

The representation of Rosa Parks differs because she is absorbed by her stand against segregated bus seating laws is placed in a context of Black Lives Matter agitation up to the present. Something of the humility of Parkes shines through that goes along with her resistance to laws that demeaned black people in the USA.

Marie Stopes too is represented as a representative woman, a woman absorbed in the meaning of her task to free women from the hold arguments about female destiny as inscribed in basic biological difference. Stopes is represented as the beginning of a process in which women will become free to choose pregnancy, or its avoidance not at the behest of men – represented here by aggressive spermatozoa cause female (represented as edible eggs with a yolk and joke face) eggs to run in flight from them

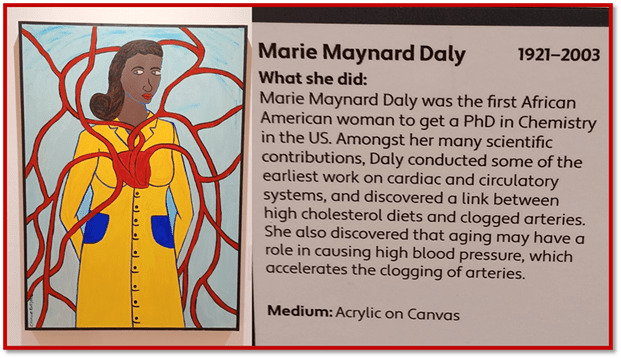

That picture seems to scream out that female achievements matter more when they address the content of female oppression in ideology, or its potential to create greater and more durable webs of intercommunication that affirms the value of women and the values that women have acculturated as a result of more limited collusion with capitalism than men. I did not know of the life of Marie Maynard Daly, but the representation of her as the heart of a web of vascular networks, suggests that a life of service might itself be a value that femininity has fostered and that ought to be absorbed without the binary construction of humanity being its pathway. Nevertheless Marie seems trapped behind the network whose significance she has discovered, in a way a male explorer of the body would not have been.

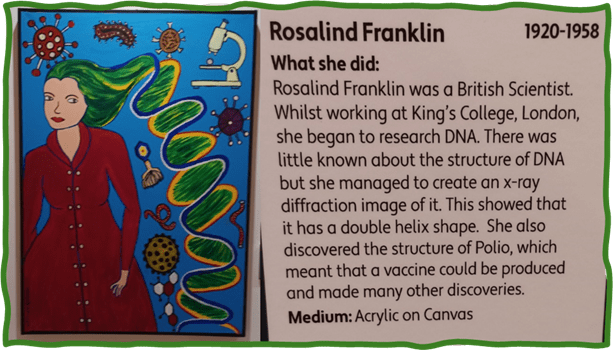

Similarly I love the way the iconography of Rosalind Franklin’s achievements is absorbed into imagery of female stereotypes, such as the long hair of Rapunzel, made for men to climb, whilst keeping her locked in. The long hair becomes the double helix of DNA, Whilst Franklin uses it as a means of defence against the aggressive micro-organisms that threaten, just as spermatozoa threatens Stopes and her generalised client.

In the end though, I felt the viewer needed to do too much to stop the exhibition being just a show about rendering more visible woman of incredible achievement, without attacking the ideology that keeps woman in a sex/gender web in which they are continually re-trapped.

However the Town Hall has a secondary exhibition of local women. One element of civic portraiture of one woman who made it despite sexism and misogyny strikes an old-fashioned and appeasing note for patriarchy to hear, but the art that reaches out to female communality as a continual restructuring process seems to me more telling. Here is Richard Bliss’s (for an earlier blog on his exhibition of male shirts use this link) . His fabricated dress is a collage of representations of spaces in which women came to challenge male dominance whilst supporting men they knew to be also oppressed, even though they could be oppressors too. Yet it deconstructs the labels that started off originally as just about men and recalls equally the clothing of women’s suffrage.

Next to it is a monochrome photograph of the Newton Aycliffe Women’s Section of Sedgefield Labour and Trades Union movements. It attests to a coming together of women across difference to build a newly constructed order that need never be subservient to the values associated with masculinity – individual competitive strength and a determination to make the world work just for you without changing it. The phrase ‘We live for Others’ feels an important statement herein.

Go and see the exhibitions if you can – and decide for yourself. Discussion, and commentary that might open my sleepy old man eyes is welcome,

With all love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx