Superstition is very often a word that is pre-loaded with value judgments. In mainstream modern usage, with justification in the use of it by the ancients and in the history of Christianity. Rarly and continuing internal disputes in Christian tradition is larded with name-calling (in which being ‘superstitious’ is a claim made against sects being labelled as false or heretical). The use of the term hence equates with a meaning that can be stated thus:

‘”false religious belief or system, worship of pagan gods; ignorant fear of the unknown and mysterious, irrational faith in supernatural powers,” from Latin superstitionem (nominative superstitio) “prophecy, soothsaying; dread of the supernatural, excessive fear of the gods, religious belief based on fear or ignorance and considered incompatible with truth or reason.” (from Etymonline: https://www.etymonline.com/word/superstition)

Now no-one answering this question is likely to say that they are prone to ‘false’ or even erroneous beliefs, though I suspect we all have them and some of them regulate their cognitive – affective belief systems. For some, any religious belief is a distortion as implied by the graphic below:

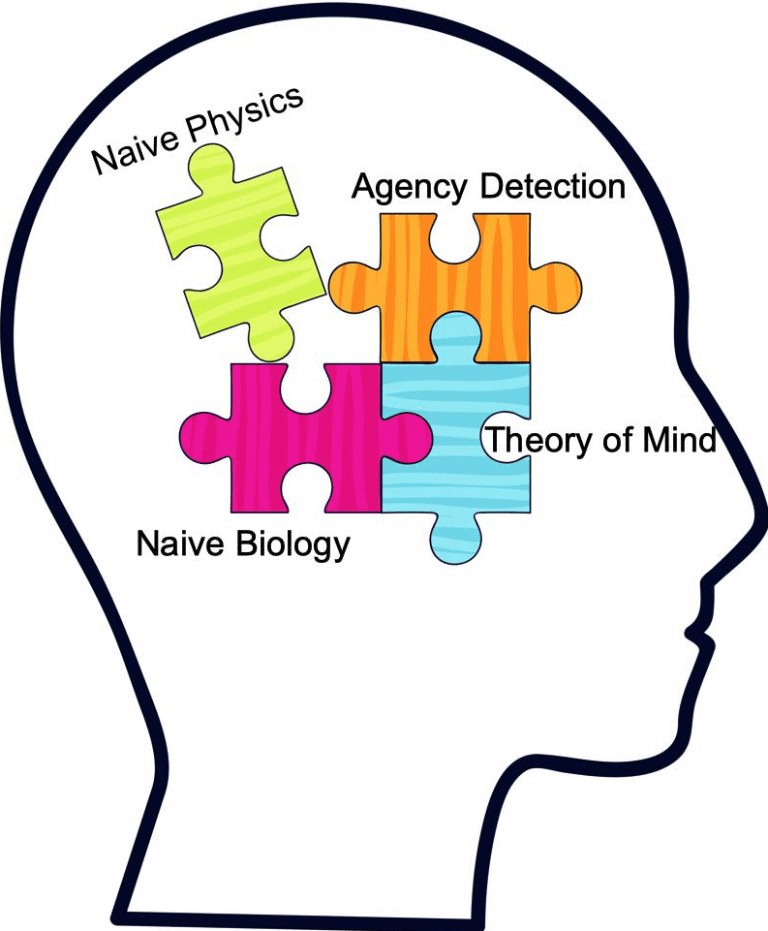

All of the components of the mind jigsaw above can be use to explain religious belief and emotional response to that belief by sceptics of the validity of any religion or formalisation of a spiritual realm distinct from the physics of the real world. The ‘real’ world is knowable only through uncertainty about any generalisation, by testable hypotheses.

Depth versions of cognitive-behavioural theory talk about work on ‘core beliefs’ to change very entrenched behaviours and emotional responses that might be the product of early trauma, but not all such theorists believe, as Freud very definitely did, that the forms of religious belief and emotion are products of early experience or its cultural formalisation over time.

Within the Christian religion, ‘superstition’ is a false version of the self-same religion in which some common beliefs are shared. Wikipedia, in a contested article, uses the religious ancients (not in the initial case Christian believers but believers nevertheless in a religious system equally liable to psychic ‘splitting’) expresses it thus:

In antiquity, the Latin term superstitio, like its equivalent Greek deisidaimonia, became associated with exaggerated ritual and a credulous attitude towards prophecies. Greek and Roman polytheists, who modeled their relations with the gods on political and social terms, scorned the man who constantly trembled with fear at the thought of the gods, as a slave feared a cruel and capricious master. Such fear of the gods was what the Romans meant by “superstition” (Veyne 1987, p. 211). Cicero (106–43 BCE) contrasted superstitio with the mainstream religion of his day, stating: Nec vero superstitione tollenda religio tollitur – “One does not destroy religion by destroying superstition”. Diderot’s 18th-century Encyclopédie defines superstition as “any excess of religion in general”, and links it specifically with paganism.

In his 1520 Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, Martin Luther, who called the papacy “that fountain and source of all superstitions”, accuses the popes of superstition:

For there was scarce another of the celebrated bishoprics that had so few learned pontiffs; only in violence, intrigue, and superstition has it hitherto surpassed the rest. (Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superstition)

That superstition is used as a stick by religions that call themselves the one and only truth to beat up alternative version of that truth is the sure sign of a concept born out of psychological splitting. Splitting is a psychological defence mechanism that, for the infant, in Melanie Klein’s psychodynamic thought, differentiated ‘good breast’ that sustains you, cares and is always there for you from ‘bad breast’ which is capricious, has its own agenda and can be treated as evil in intent, whatever the truth. It also lies behind the psychic splitting that creates the paranoid-schizoid as a permanent position in Fairbairn’s extension of Klein.

In Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, the true religion (that of the established Church of England with roots in the Eastern Byzantine Empire) is allegorised as Una, against the false ‘Duessa’ (or doubleness – splitting in fact) ruled over by the magician, Archimago, oft the shade of the Pope.

For atheists like myself, this splitting is inevitable in religions which pretend that the truth is one unity, split only by having to live in a fallen world, in which evil is given sway in order to test the one true faith. As always the truth of believers in a unified one truth is also a shadowy dualism of the binary of one truth versus many false claims of truth but run wild. In those systems, self confronts what is other only either to convert it to one like unto itself or condemn it as the evil that it only pretends not to be. Any true superstition is to pretend that uncertainty is a thing we have to live with but not condemn, accepting that truth is never knowable in one formulation only, although it still can be distinguished from unsustainable lies.

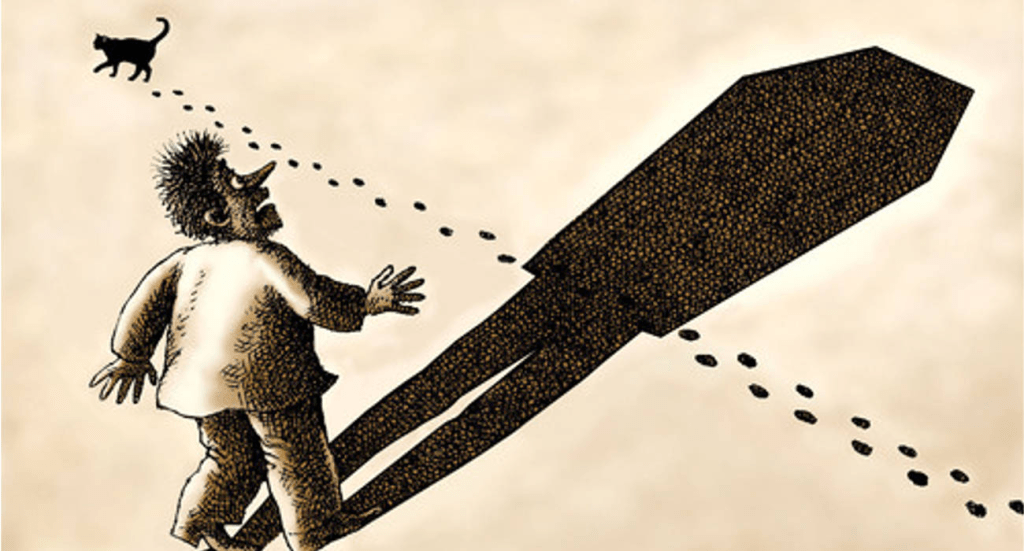

But by ‘superstitious’, this question probably means: do you give undue meaning to black cats, ladders or the unexplained? The answer is – more than I like to admit. I think the search for reassurance in a world that contains so much that is unacceptable, even in our own behaviour and collusion with that of others, that we tend to all rely on symbols that promise to waylay doubt and sustain hope, even if just for a while. Even more so, we believe in supernatural extensions of evil as an explanation for the explainable otherwise, for they help simplify our experience of grotesque human behaviours- like abuse – in ways that allow us not to linger on them for causes. Yes, I do this too! Does that mean I am ‘superstitious’ despite myself! No doubt. However, I cannot conclude anything from that fact other than we sometimes need to hold onto error as well as truth, until we learn what distinguishes them and what they have in common.

All for today

Love Steven xxxxxxxxxx

I will say that truth and belief lie in different domains. What is true is true. It does not require me to believe it in order to be so. My disbelieving it doesn’t make it not so.

I would argue that all religion is superstition. As Stevland Morris (Stevie Wonder to most of us) said, “If you believe in things you don’t understand, then you suffer. Superstition ain’t the way.” Religion is a way to “explain” (believe something about) that which we don’t understand.

I think it is important to recognize the difference between not believing something and believing the opposite. Agnosticism (not knowing) is not the same as a belief that there is no god.

(You can thank, or blame, WordPress’ algorithm for sending me here from my own post today.)

LikeLike

Though I think what you say is cogent, it does not solve the problem. That truth exists independently of belief would not make it no clearer how that truth can be known and expressed (that is we solve the ontological problem but not the epistemological one). If I take your argument as given, which I don’t necessarily, then the fact that truth exists ontologically does not give me access to knowledge about it without some means of knowing what it is is. Science is a means thought to show us what a thing is but its results only give us provisional truths – truths supported by present discovered evidence. Certainty is never but provisional. The other means of knowing will always depend on a degree of belief that a thing is so and that these are its qualities. In thinking about it I am fairly sure that even the ontological issue involves belief.

Nice to meet you by the way.

LikeLike