‘Would You Let Yourself In’ : Leigh Bowery’s inclusively exclusive or exclusively inclusive dilemma and other contradictions inside Leigh’s outside keeps us outside his inside. This is my blog reflecting on visiting the new Leigh Bowery exhibition at Tate Modern with the help of it the Tate’s publication Alice Chasey (Senior Ed.) [2025] Leigh Bowery! London, Tate Publishing.

Fiontán Moran in the introductory essay, and probably best essay in it, to the book serving to commemorate this exhibition, Leigh Bowery!, tells, amongst other things of Bowery’s long relationship to night clubbing and especially the club night called Taboo at the Maximus night club on Leicester Square, frequented by celebrities of the time:

You’d have Marc Vaultier on the door bitchily asking badly dressed people “would you let yourself in?”, Trojan sauntering around the dancefloor, Auburn DJing on the decks, Sue Tilley holding court in a booth, Boy George in the toilets, Nicola Rainbird unveiling a new headpiece, and a host of regulars doing synchronised dance routines and then rolling around on the floor; with celebrities ranging from George Michael to William Burroughs.[1]

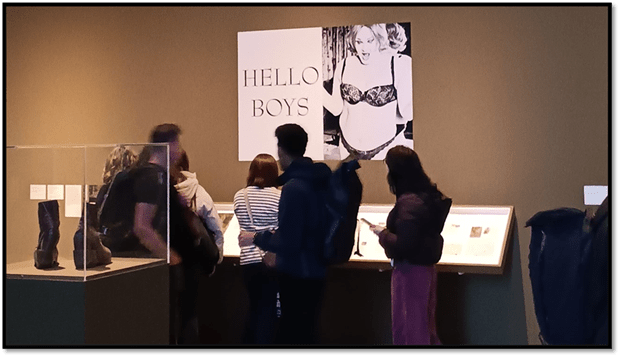

The story has another detail when told in the Tate’s webpage describing the show that tells us that Vaultier accompanied his question, with props: he ‘would hold a hand-mirror up to badly dressed punters and ask: Would you let yourself in? ‘. In the show this is represented by a large unframed wall mirror with the same question printed on its surface. Bold visitors stand in front of it and took reflected selfies. I scurried past not looking at it all. The idea of what you think about your ‘look’ is clearly central to this show.

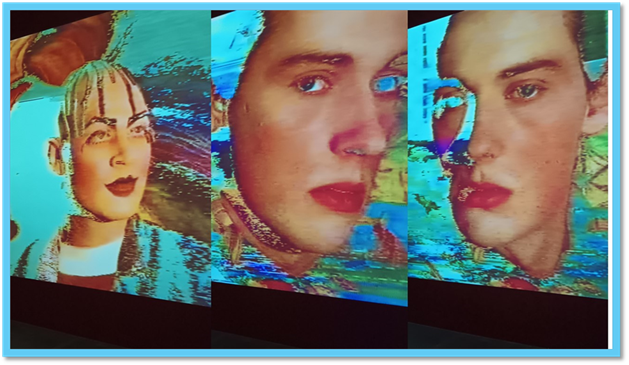

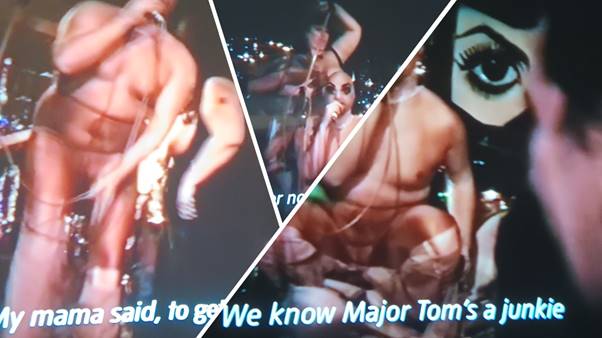

For instance, the screened performance art piece above (Charles Atlas’ Teach 1992/1998, video) works by the virtue of interactions between the relentless gaze, given its duration, performed by Bowery on the viewer, the pained continuance of the appearance of the face with its tightly sewn up and skewered facial.parts, and the discomfort this impels into the gaze of the viewer disliking to stay looking or glance or walk away from that tripartite looking enactment. That piece recalls another piece featuring Leigh where the stitching of skin transformations is the focal subject (Baillie Walsh Unstitched 1990 – see both together ibid: 136f.). That the piece is projected next to a portal of escape for the viewer into another room.us important .

But both appearance and the gaze, since they are both possible meanings of “the look’, are strange tools of self-expression and usually discourse about the ‘look’ is organised in terms of binaries that sometimes lift that discourse into the sphere of ontological questions (questions sbout the nature of bei g or existence) – binaries like appearance and reality, self and other, surface and depth, external and internal markers of character, outsides and insides. It is within the exploration of these ontologies that I would place Leigh Bowery. He is certainly not a radical proponent of the identity politics of the period with which he was associated. This blog is my attempt to fill out that opinion, together with my unease about the Bowery phenomenon, which implicated so many artists including Lucien Freud.

We could start with the issues raised by the art of Stephen Willats, who sees, in his art and his essay (the former reproduced with the essay) in the book aforementioned, the discontinuities in Leigh’s self-conscious referencing of his life as divided between living ‘in’ the day and loving, working and playing ‘out’at night. The words below are respectively used to comment on an image of the tower of flats, Farrell House, containing one shared by Bowery and Trojan (real name Gary Barnes) in the day and at night, with images of interior and exterior artifacts respectively too. The images form the left and right of a diptych. The words on each are:

{LEFT}:

WHAT IS HE TRYING TO GET AT ~~~~~~> Once I’m in, I’m really in. Everything’s shut outside. I can look down and say I’m quite safe in this position, as though I’m in a spaceship or something, just hovering above everything.

{RIGHT}:

WHERE DOES HE WANT TO GO ———-> I suppose it’s like a sort of advocating tolerance, you know, don’t criticize or be hostile to anything that’s different or unusual or something that you’re not familiar with.

The whole forms a kind of grand over-riding contradiction based in the notion of social group formation. After all, there can be no social group, however ‘inclusive’ (pr even ‘tolerant’ of difference between its own members and others ) that does not define itself and delimit its boundaries by some kind of exclusion, for all kinds of reasons including the resistance to being in the group of some outsiders and a lack of desire to be ‘in’ it by others. Here is the problem of the idea of looking at yourself and asking: ‘ Would you let yourself in?’ The condition of being ‘in’ and ‘in-group’ must contain some agreement, collusion or faking of its norms, even under provocation to reject them. This is the contradiction Leigh constantly tried to render a performance of their being. He tested his audience’s for their fitness, not without some intolerance of their doubts. Take, for instance, his performance of an on-stage enema for a HIV Benefit Night show at The Fridge in 1994, where he appeared naked except for the taping down of his penis to make it invisible and squirted liquid from his anus when bending over, inadvertently (or so he said) covering the front rows of the audience with the ejected liquid. [2]

That this is not ‘identity politics’ is a point made by Prem Sahib regarding the performance piece P*kis From Outer Space. They recall how Bowery spoke to their need for ‘expressions of sexuality and gender’ that he was ‘so desperately seeking’ in the 1990s. But getting in to Heaven or The Fridge on the appropriate nights required that Sahib dragoon their whole family into making costumes resembling Bowery’s looks as photographed by Fergus Greer (see below some from the exhibition) – his Aunt sewing into outfits plastic tablecloths that looked like PVC worn by Bowery or welding metallic objects secured by his Dad and Uncle.

However, Bowery’s P*kis From Outer Space, though intentioned as a means of critiquing the everyday racism of sections the White working-class, looked to Prem quite unlike ‘tolerance’ of ‘anything that’s different and unusual’ (Bowery thought the premise of the whole thing was that that it was white normality that rendered Asians in London as if ‘aliens’). Sahib sensed that far from being inclusive of Anglo-Asian cultural difference, however revised, it excluded consciousness of Asian experience of racism:

the pain of a community whose anti-racist organising was waged through hardship and violence; of street attacks on people like my dad, who was stabbed iun the leg by the National Front, or my uncle, who was driven outside of London by police, dropped off and told “walk back you Paki”, …. [3]

That is the issue, or part of it – in the end, at night under cover of dark, Bowery could ‘go out’ dressed to be seen in the supposed interests of tolerance for those who could or would not meet certain expected social norms, but did so by having a day full of protecting and safeguarding themselves from anything like the worlds others felt they could not escape for the sake of their families of other networks, who were unable to be ‘let in’ by the gatekeepers of Taboo, or the norms that eschewed those who would not differentiate themselves and their ‘look’ to make the point about the everyday being the true ‘alien’ lifestyle.

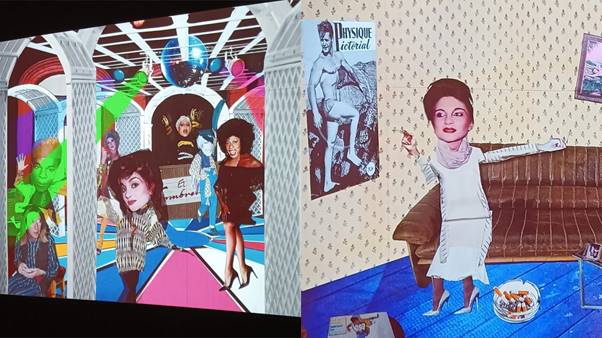

In their flat, Bowery and Trojan fashioned a safe anti-normal space, from the black back-grounded Star Trek wall paper – reproduced in Room I of this exhibition to the clothes rails of totally distinct outfits, that allowed for change frequently, and loo roll on the wall where they were not expected to be, as in Trojan’s painting of Bowery right in the collage above.

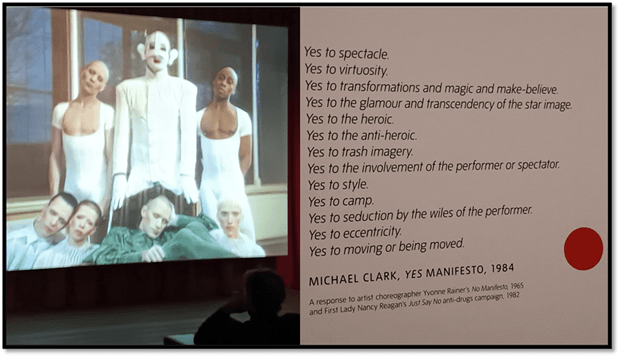

An excerpt of the film made of this daytime in-space was made that included Michael Clark, Rachel Auburn, Trojan and Leigh ‘playing’ themselves’ using the day to prepare for the night and to ‘go out’. But this ‘in-space’ is marked, in the way the people perform themselves vy constant ‘bitching’ (a misogynistic word that ought not to be avoided because it applies most to the males in the film) – especially against Rachel for refusing to dress in conformity with the standards expected by Leigh for ‘coming out’: “What’s she like?”, he whispers – stage-whispers – to Trojan. Below Rachel (top right bends to the mirror to check her fitness).

Clark saying he ‘looks like a school mistress’ in connection with the varied codes of his garb – a tartan kilt, leather jacket, teddy boy hairstyle – shows that to be fit one must attempt not to ‘look’ like anything recognisable by convention and traditional norms. Once has to be continually making and re-making yourself – being ‘in’ when you are ‘out’ and not in your ‘in-space’ is a constant battle. It amazed me to see these games played in the White House this weekend when Trump and Vance accuses President Zelensky of Ukraine of disrespect to America because he did not wear a ‘suit’ in the Oval office.

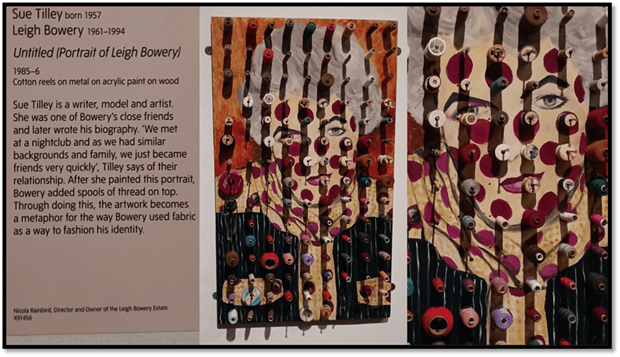

Yet Bowery’s in-group made made remaking images even from newly made ones their trade-mark – a logo that never stays the same is not, of course, a logo. It refuses to conform to expectations from anyone, one reason Bowery disliked the imagery of Gay Pride. Sue Tilley’s portrait of Leigh is a wonderful one to see in the flesh at the exhibition:

Its theme always was that Leigh fashioned identity from constant reidentification from the ruins of old identities, But Leigh continued the theme by remaking Tilley’s art as soon as he received it as a gift – see the information left on the collage above.

Stepping out and looking out from fabric that covers one’s entire body, except for eyes and mouth usually, is another sign of how old markers of identity must be suspended. Even his flat, as previously described was not a flat with self-identifying decoration but an art installation calling for re-fashioning. Jeffrey Gibson, for instance, says he was, with other of Leigh’s friends, ‘helping him to realise his world’, as an expression of the artistic intellect. But the aim is, though Bowery called his ‘in-space’ ‘safe’ is not that of comfort in safety (the bourgeois pursuit of at-homeness) Gibson also says of his fashioning of place, self-in-costume changes, and performative relationships, as :

so clearly somebody who was interested in making people uncomfortable. At that time, I just thought, I feel uncomfortable looking at this, I feel uncomfortable letting myself enjoy this., I feel uncomfortable even understanding what is going on here. /…/ He was even offending people who loved weird shit. … [4]

I so agree with Gibson too that Leigh is avoiding labels perpetually in a way that sometimes makes those of us who self-label in contradiction to norms even uncomfortable. Hi goal Gibson shows inu to perform ‘something’ but to perform performing and that includes constant flux between things. Hence Gibson says neither they nor friends thought his act to be a form of ‘drag’ He goes on to say that it is about ‘masks’ rather than ‘disguise’ and that they are most ‘themselves’ in their constant dissolution, treading the border of illegibility (being unreadable). This is the meaning perhaps of this beautiful film loved by most contributors where colour and form are neither stable nor do they distinguish inside from outside of the form but keep pentrating or being penetrated by it in constant painless flow, even of the boundary frames of faces and body parts.

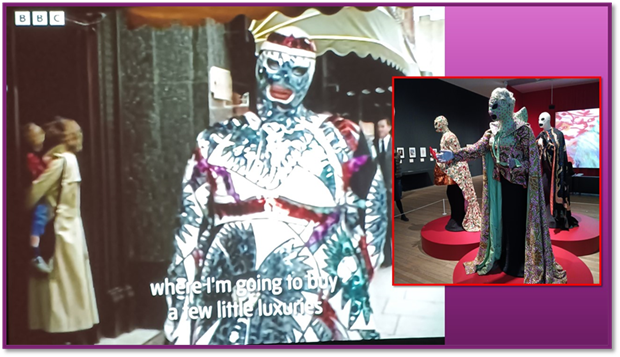

When covers his reshaping with fabric all over, he becomes the commodities he might buy in Harrods – in the BBC film below he was filmed visiting Harrods for ‘a few little luxuries that I find I can’t live without’ – (or pick up unwanted elsewhere) without being a commodity others want, though they are intrigued by the Look< meanwhile for some the whole concept becomes a satire of commodity culture.

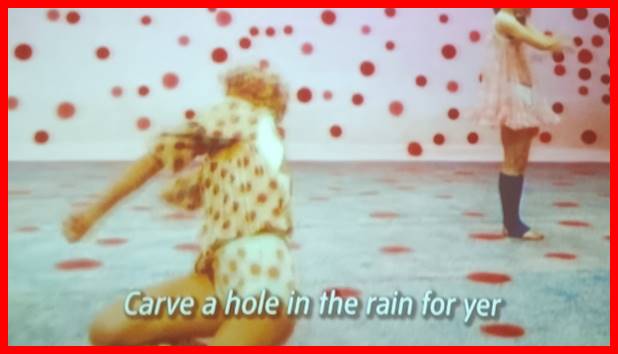

An example where boundaries were overstepped that make radicals uncomfortable was in the Maybury film ‘All Hail the New Puritans’ where spots where used as clothes and as icons of make-p and in their scatter mimicked Karposi’s sarcoma – the skin cancer most identified with HIV/AIDS at the time (1986). I felt and feel still uncomfortable with this imagery given the reality of HIV/AIDs experience at the time, and now.

Likewise I have issues with the violence and horror of some blood-ridden images – however playful the intention. That may be my problem. I am open to that interpretation.

The images created come at you. Their performance and distortions, based originally on Punk, are deliberately, as Princess Julia says, created to make ‘you look and feel fierce’. [5] And perhaps ‘dangerous’. Was that because the sanctimonious bourgeoisie deserve it, or the marginal had been meek too long, or was it hust testing the boundaries of images used JUST to make yourself seem safe from the unfamiliar.

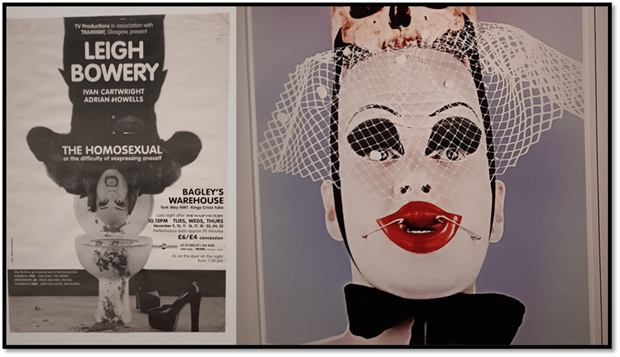

THe age of ‘positive images’ was in itself suspect, as in Bowery’s playabout in the show The Homosexual, where Leigh is ‘inverted’ (itself a joke about gay identity, with his head about to be lowered into a flowery toilet bowl. , standing next to high-heels reinforced for drag use by a heavy man. The calls gat marriage may be satirised in the picture on the right below. The headdress is a skull, above a bridal veil hanging over a flat mask with Dali-like lips pinned into a smile, an d a black bow-tie rhyming wwith eye-shadow that is most extreme..

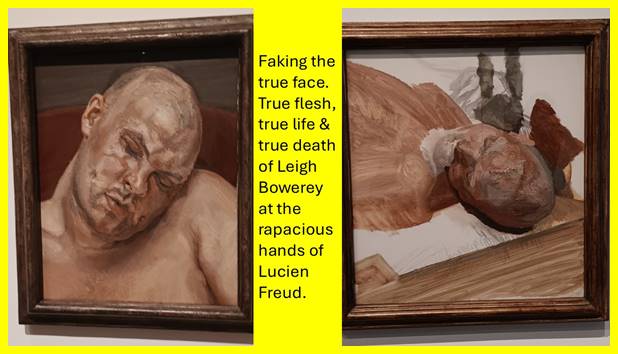

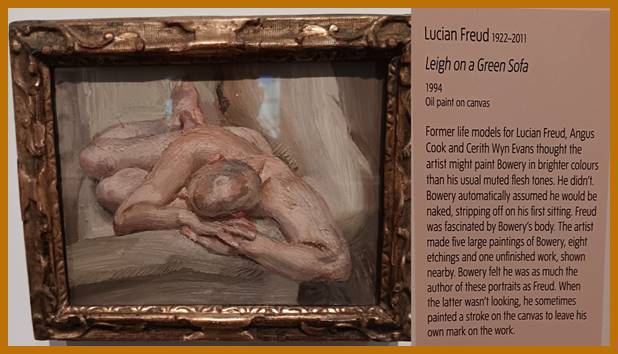

Perhaps I learned most in this show however about the work Bowery did with Lucien Freud. The paintings, some of which I have never seen before as well as some favourites (left below for instance). Bowery was introduced to Freud by Cerith Wyn Evans, who writes in the catalogue, and was Freud’s friend’s, Angus Cook, girlfriend at the time. According to Wyn Evans Freud loved Bowery as an example of his admiration for queer men generally, although it is an admiration that does not show in Feaver’s biography, She says: ‘For Lucian, queers had integrity and resilience – they had to stand up for themselves’. [6] But as other commentators show too, what Freud did yoo Bowery was to render his flesh another mask – perhaps below death masks – and to fragment him into parts. The study I have never before seen on the right below – shows Freud developing his brush stroke to render skin as leather, that looks alive but may not be.

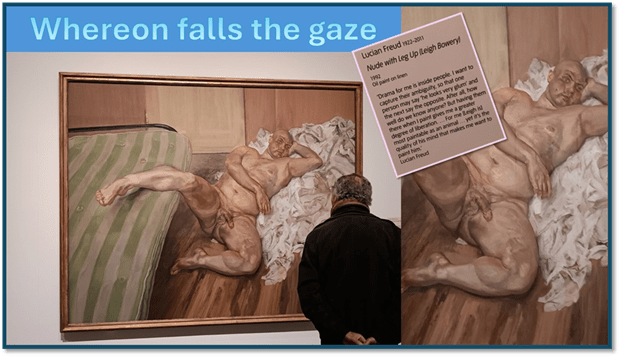

And Freud clearly too was fascinated by Bowery as a sexual being. The body below undergoes considerable distortion to make the phallus of Leigh the focal point of gaze, uncomfortably so for some viewers.

In a detail oil study, the phallus almost segmented such that it can be felt as if in pain, while apparently relaxed. This is the part picture of all.

Leigh is ‘cabin’d, cribb’d, confin’d’ in the famous portrait below as he is turned into a perspectival exercise that partitions him. It is great Freud but yet another Bowery performance of mortality.

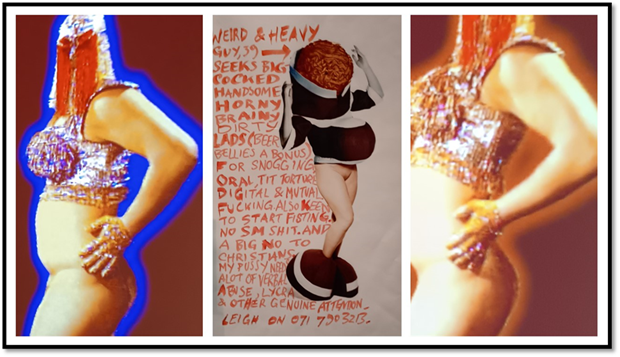

Of Bowery’s interest for omen, I cannot comment – though I would once have confidently analysed satirical play in the images below. Hence I will leave them for any viewer still with me to decipher:

Where satire is clearly intended, it is aimed at the distortions of the concept of the everyday rather than sex/gender. He attacks norms by queering them.

This is the case for instance in a piece which alternates images of the Thatcher of Section 27 with other images onto a hanging curtain of chain mail, so that show through on each side of them.

What do we make of this costume? In part it is about being displayed in a vitrine where other art images becomes its context and interpretation frame. But I get very little distance in this work, while remaining fascinated.

See that costume on however and we see its virtue is in another idea of how the performance of the body allows for mixed non-binary imagery, even influence by the lighting of body boundary

But linger n the advertisement for a boyfriend in the advert central in the collage above, and all we get is something definitely not there for satire or even to bend gender, but to show that sexual desire is itself already bent in what we call normality – a list of requirements that are not easy to decipher – not everyone, for instance differentiates ‘fisting’ from SM Shit.The famous slogan ‘Hell Boys’ plays to this gallery of what Bowery sees as perverse, which is normality – but not in a bad way if perversity is given its head.

In the end, the poem below, in the collage, says what this is all abou – it is about the play with signifiers we call art, not about giving prominence to one hegemonic set of signifiers and calling it ‘reality’ or ‘normality’.

And that extends to the artistic fashioning of boots too:

I think you should see this exhibition if tou can. I came out of neither feeling included nor excluded but a bit of both. Here, I thought was a place and space for experiments with the interplay of thoughts, feelings AND values. If you come out of it with some values still challenged, that is no bad thing. I am still not sure whether or not to ‘let myself in’! Fiontán Moran ends his piece in the book saying:

So we are left to look into our own mirror, and ask what might be found if we move beyond appearances and into the unknown. Would you let yourself in?

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Fiontán Moran (2025: 15) ‘Inverse Reverse Perverse’ in Alice Chasey (Senior Ed.) Leigh Bowery! London, Tate Publishing, 10 – 23.

[2] ibid: 20. There is a photograph of the act in the catalogue (ibid: 122f centre-fold) , which I am not allowed to reproduce.

[3] Prem Sahib (2025: 219) ‘At Home with Leigh’ in Ibid: 218 – 221.

[4] Jeffrey Gibson interviewed by Margery King (2025: 170f.) ‘Jeffrey Gibson and Leigh Bowery’ in ibid: 170 – 177.

[5] ‘When in doubt, go out’: At home with Princess Julia and Jeffrey Hinton’ (2025: 54) in ibid: 54 – 59.

[6] Cerith Wyn Evans (2025: 25) ‘God Bless You Liesl, from Spritzer’ in ibid: 24 – 25